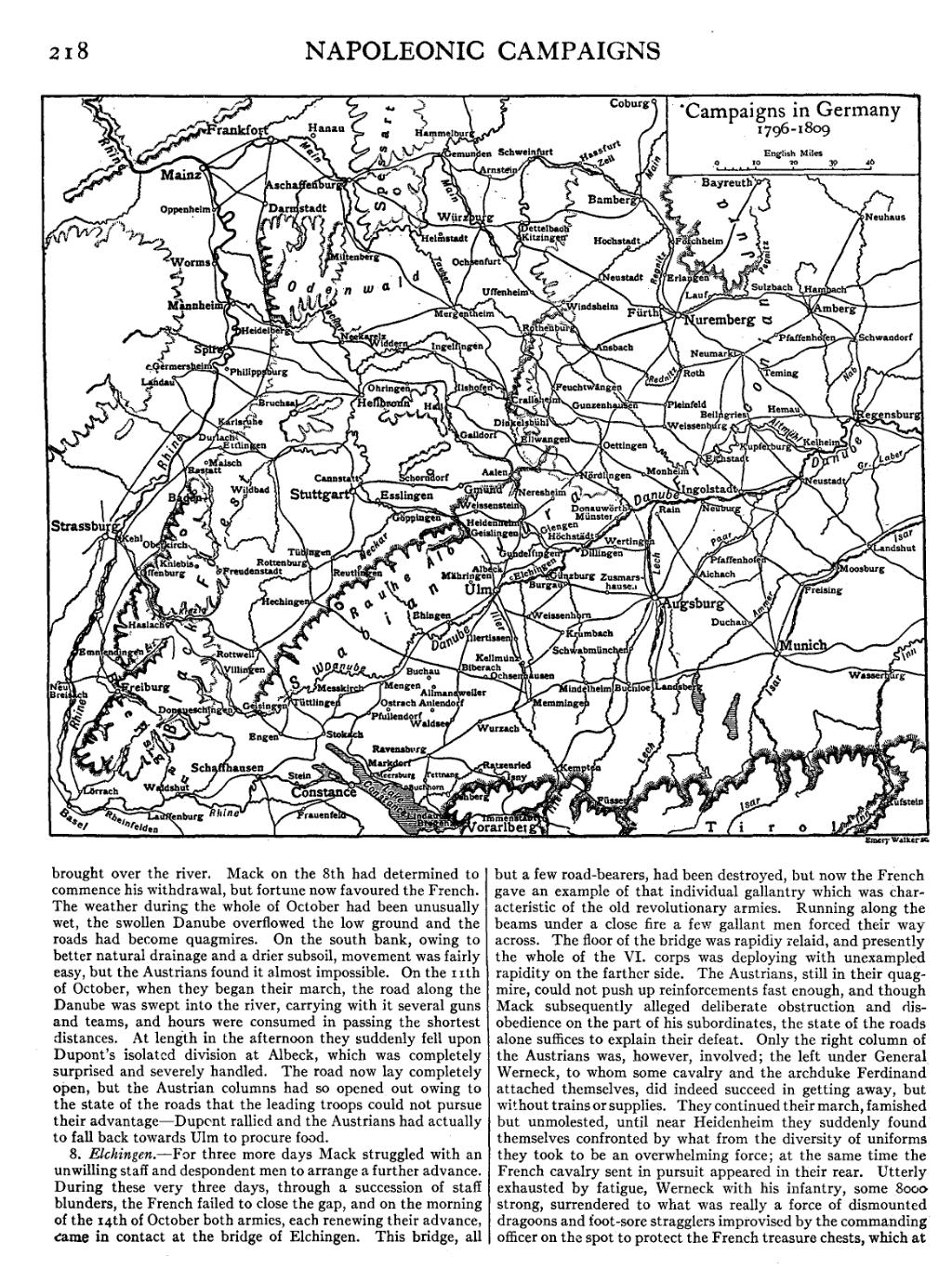

brought over the river. Mack on the 8th had determined to commence his withdrawal, but fortune now favoured the French. The weather during the whole of October had been unusually wet, the swollen Danube overflowed the low ground and the roads had become quagmires. On the south bank, owing to better natural drainage and a drier subsoil, movement was fairly easy, but the Austrians found it almost impossible. On the 11th of October, when they began their march, the road along the Danube was swept into the river, carrying with it several guns and teams, and hours were consumed in passing the shortest distances. At length in the afternoon they suddenly fell upon Dupont’s isolated division at Albeck, which was completely surprised and severely handled. The road now lay completely open, but the Austrian columns had so opened out owing to the state of the roads that the leading troops could not pursue their advantage—Dupont rallied and the Austrians had actually to fall back towards Ulm to procure food.

8. Elchingen.—For three more days Mack struggled with an unwilling staff and despondent men to arrange a further advance. During these very three days, through a succession of staff blunders, the French failed to close the gap, and on the morning of the 14th of October both armies, each renewing their advance, came in contact at the bridge of Elchingen. This bridge, all but a few road-bearers, had been destroyed, but now the French gave an example of that individual gallantry which was characteristic of the old revolutionary armies. Running along the beams under a close fire a few gallant men forced their way across. The floor of the bridge was rapidly relaid, and presently the whole of the VI. corps was deploying with unexampled rapidity on the farther side. The Austrians, still in their quagmire, could not push up reinforcements fast enough, and though Mack subsequently alleged deliberate obstruction and disobedience on the part of his subordinates, the state of the roads alone suffices to explain their defeat. Only the right column of the Austrians was, however, involved; the left under General Werneck, to whom some cavalry and the archduke Ferdinand attached themselves, did indeed succeed in getting away, but without trains or supplies. They continued their march, famished but unmolested, until near Heidenheim they suddenly found themselves confronted by what from the diversity of uniforms they took to be an overwhelming force; at the same time the French cavalry sent in pursuit appeared in their rear. Utterly exhausted by fatigue, Werneck with his infantry, some 8000 strong, surrendered to what was really a force of dismounted dragoons and foot-sore stragglers improvised by the commanding officer on the spot to protect the French treasure chests, which at