and also the invention of a special kind of balance, which goes by his name.

His works were published in 1693 by the Abbé Gallois, in the Recueil of the Mémoires de l’Académie des Sciences.

See J. A. N. de C. Condorcet, Eloge de Roberval (Paris, 1773); J. E. Montucla, Histoire des mathématiques (1802).

ROBES (Fr. robe, Late Lat. roba, raupa, meaning (1) spoils, (2) robe, stuff, cf. Mod. Ital. roba, connected with a Teutonic root raup, raub, German rauben and English rob), the name generally given to a class of official costume, especially as worn by certain persons or classes on occasions of particular solemnity. According to Du Cange, the word .robe was earliest used, in the sense of a garment, of those given by popes and princes to the members of their household or their great officers. Thus Matthew Paris (Chron. Majora, Rolls Series, V. 38) tells how, in 1248, the pope gave to some Tatar envoys “vestes pretiosissimas quas Robas vulgariter appellamus, de escarleto praeelecto, cum pellibus et furruris,” with which Du Cange compares the “festiva indumenta” given, e.g., by King John magnatum suorum multitudini at Christmas time (1214, Matt. Paris, 'Rolls Series, II. 520) and the raubae papales scntiferorum, and the like, given by the popes to members of their households, after the fashion of a livery. It would, however, 'be perhaps going too far to assume that, e.g., peers' robes were originally the king's livery, for there seems to be no proof that this was the case; but it is curious that in most early cases where robes are mentioned, if not of cloth of gold, &c., they are of scarlet, furred. A robe is properly a long garment, 'and the term “robes” is now applied only in those cases where a long garment forms- part of the official costume, though inf ordinary usage it is taken to include all the other articles of dress proper to the costume in question. The term “robes,” moreover, connotes a .certain degree of dignity, or honour in the wearer. We speak of the king’s robes of state, of peers’ robes, of the robes of the clergy, of academic robes, judicial robes, municipal or civic robes; we should not speak of" the robes, of a cathedral verger, though he too wears a long gown of ceremony, and it is even only by somewhat stretching the term “probes” that we can include under it the ordinary academical dress of the universities. In the case of the official costume of the clergy, too, a distinction must be drawn. The vestimenta sacra are not spoken of as “robes”; a priest is not “robed” but “vested” for Mass; yet the rochet and chimere of an English bishop, even in church, are more properly referred to as robes than as vestments, and while the cope he wears in church is a vestment rather than a robe, the scarlet cope which is part of his parliamentary full dress is a robe, not a vestment. For the sake of convenience the official, non-liturgical costume of the clergy is dealt with under the general heading Vestments and the subsidiary articles (e.g. Cope).

The coronation robes of emperors and kings, representing as they, do the sacerdotal significance of Christian kingship, are essentially vestments rather than robes (see Coronation). Apart from these, however, are the royal robes of state; in the case of the king of England a crimson velvet surcoat and long mantle, fastened in front of the neck, ermine lined, with a deep cape or tippet of ermine.[1]

The subject of official robes is too vast for any attempt to be made to deal with it comprehensively here. All countries, East and West, which boast an ancient civilization have retained them in greater or less degree, and the tendency in modern times has been to multiply rather than to diminish their number. Even in republican France they survived the Revolution, at least in the universities and the law courts. But nowhere has custom been so conservative in this matter as in the United Kingdom, where in this as in other matters the wise Machiavellian principle has been followed of changing

the substance of institutions without altering their outward semblance. The present article, then, does not attempt to dealt with any but British robes,[2] under the headings of (1) peers’ robes, (2) robes in the House of Commons, (3) robes of the Orders of Knighthood, (4) judicial and forensic robes, (5) municipal and civic robes, (6) academic costume.

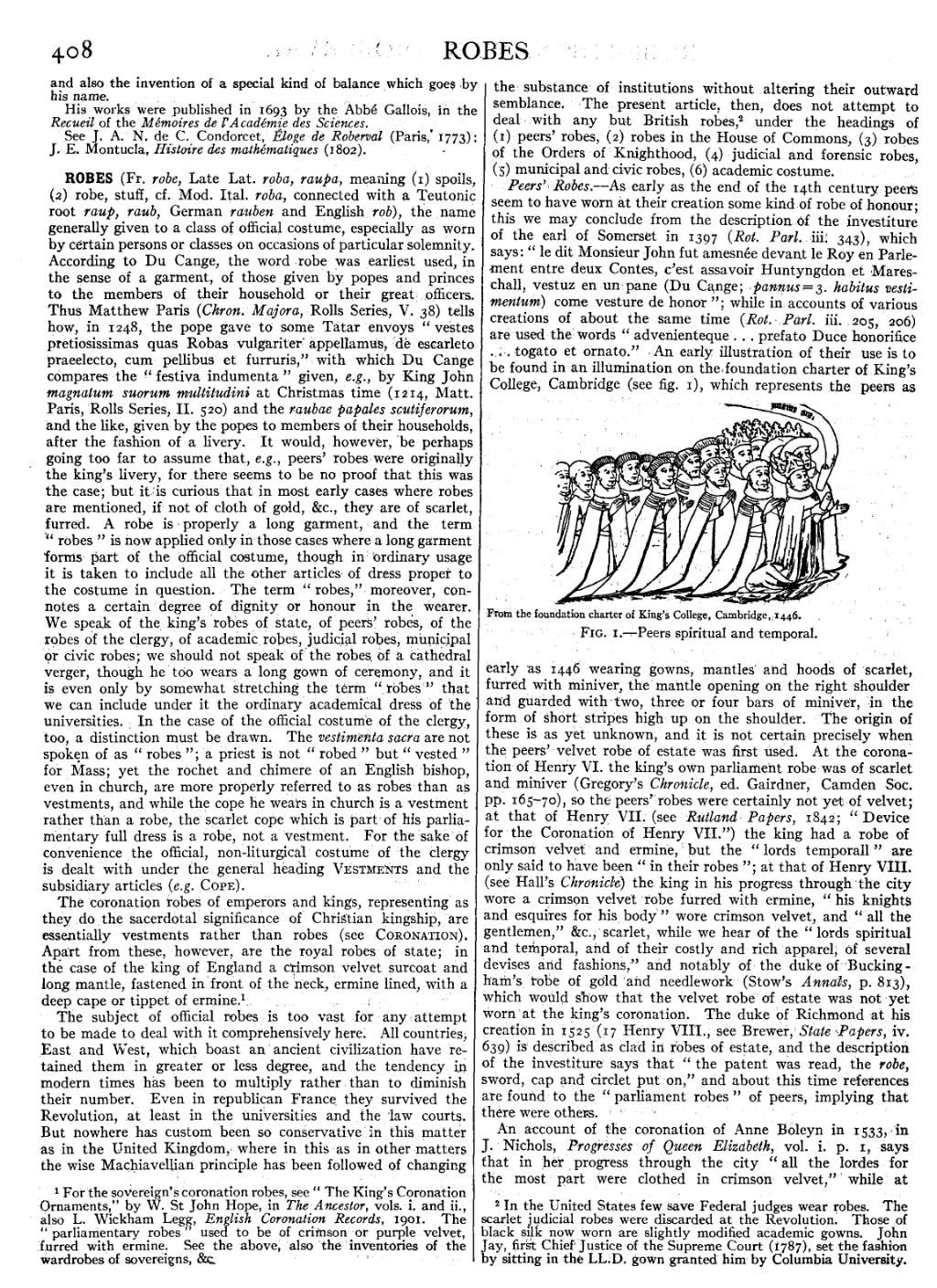

From the foundation charter of King’s College, Cambridge,1446.

Fig. 1.—Peers spiritual and temporal.

Peers’ Robes.—As early as the end of the 14th century peers seem to have worn at their creation some kind of robe of honour; this we may conclude from the descriptions of the investiture of the earl of Somerset in 1397 (Rot. Parl. iii. 343), which says: “le dit Monsieur John fut amesnée devant le Roy en Parlement entre deux Contes, c’est assavoir Huntyngdon et Mareschall, vestuz en un pane (Du Cange; pannus=3. habitus vestimentum) come vesture de honor ”; while in accounts of various creations of about the same time (Rot. Parl. iii. 205, 206) are used the words “advenienteque … prefato Duce honorifice … togato et ornato.” An early illustration of their use is to be found in an illumination on thetfoundation charter of King's College, Cambridge (see fig. 1), which represents the peers as early as 1446 wearing gowns, mantles and hoods of scarlet, furred with miniver, the mantle opening on the right shoulder and guarded with two, three or four bars of miniver, in the form of short stripes high up on the shoulder. The origin of these is as yet unknown, and it is not certain precisely when the peers velvet robe of estate was first used. At the coronation of Henry VI. the king's own parliament robe was of scarlet and miniver (Gregory's Chronicle, ed. Gairdner, Camden Soc. pp. 165–70), so the peers’ robes were certainly not yet of velvet; at that of Henry VII.” (see Rutland Papers, 1842; “Device for the Coronation of Henry VII.”) the king had a robe of crimson velvet and ermine, but the “lords temporally” are only said to have been “in their robes”; at that of Henry VIII. (see Hall"s Chronicle) the king in his progress through the city wore a crimson velvet robe furred with ermine, “his knights and esquires for his body” wore crimson velvet, and “all the gentlemen,” &c., scarlet, while we hear of the “lords spiritual and temporal, and of their costly and rich apparel; of several devises and fashions,” and notably of the duke of Buckingham’s robe of gold and needlework (Stow's Annals, p. 813)-, which would show that the velvet robe of estate was not yet worn”at the king's coronation. The duke of Richmond at his creation in 1525 (17 Henry VIII., see Brewer, State Papers, iv. 639) is described as clad in robes of estate, and the description of the investiture says that “the patent was read, the robe, sword, cap and circlet put on,” and about this time references are found to the “parliament robes” of peers, implying that there were others.

An account of the coronation of Anne Boleyn in 1533, in J. Nichols, Progresses of Queen Elizabeth, vol. i. p. 1, says that in her progress through the city “all the lordes for the most part were clothed in crimson velvet,” while at

- ↑ For the sovereign's coronation robes, see “The King's Coronation Ornaments,” by W. St John Hope, in The Ancestor, vols. i. and ii., also L. Wickham Legg, English Coronation Records, 1901. The “parliamentary robes” used to be of crimson or purple velvet, furred with ermine. See the above, 'also 'the inventories of the wardrobes of sovereigns, &c.

- ↑ In the United States few, save Federal judges wear robes. The scarlet judicial robes were discarded at the Revolution. Those of black silk now worn are slightly modified academic gowns. John Jay, first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (1787). set the fashion by sitting in the LL.D. gown granted him by Columbia University.