Mozambique in 1889, he organized an expedition with the object of securing for Portugal the Shire highlands and neighbouring regions, but the vigorous action of the British agents (John Buchanan and H. H. Johnston) frustrated this design (see Africa, § 5). Shortly afterwards Serpa Pinto returned to Lisbon and was promoted to the rank of colonel. He died on the 28th of December 1900.

SERPENT (Lat. serpens, creeping, from serpere; cf. “reptile” from repere, Gr. ἕρπειν), a synonym for reptile or snake (see Reptile, and Snakes), now generally used only of dangerous varieties, or metaphorically. See also Serpent-Worship below.

In music the serpent (Fr. serpent, Ger. Serpent, Schlangenrohr,

Ital. serpentone) is an obsolete bass wind instrument derived from

the old wooden cornets (Zinken), and the progenitor of the

bass-horn, Russian bassoon and ophicleide. The serpent is

composed of two pieces of wood, hollowed out and cut to the

desired shape. They are so joined together by gluing as to form

a conical tube of wide calibre with a diameter varying from a

little over half an inch at the crook to nearly 4 in. at the wider end.

The tube is covered with leather to ensure solidity. The upper

extremity ends with a bent brass tube or crook, to which the

cup-shaped mouthpiece is attached; the lower end does not expand

to form a bell, a peculiarity the serpent shared with the cornets.

The tube is pierced laterally with six holes, the first three of

which are covered with the fingers of the right hand and the

others with those of the left. When all the holes are thus

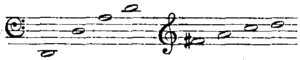

closed the instrument will produce the following sounds, of

which the first is the fundamental and the rest the harmonic

series founded thereon:  Each

of the holes on being successively opened gives the same

series of harmonics on a new fundamental, thus producing a

chromatic compass of three octaves by means of six holes only.

Each

of the holes on being successively opened gives the same

series of harmonics on a new fundamental, thus producing a

chromatic compass of three octaves by means of six holes only.

The holes are curiously disposed along the

tube for convenience in reaching them

with the fingers; in consequence they are

of very small diameter, and this affects the

intonation and timbre of the instrument

adversely. With the application of keys

to the serpent, which made it possible

to place the holes approximately in the

correct theoretical position, whereby the

diameter of the holes was also made

proportional to that of the tube, this defect

was remedied and the timbre improved.

The holes are curiously disposed along the

tube for convenience in reaching them

with the fingers; in consequence they are

of very small diameter, and this affects the

intonation and timbre of the instrument

adversely. With the application of keys

to the serpent, which made it possible

to place the holes approximately in the

correct theoretical position, whereby the

diameter of the holes was also made

proportional to that of the tube, this defect

was remedied and the timbre improved.

The serpent was, according to Abbé Lebœuf,[1] the outcome of experiments made on the cornon, the bass cornet or Zinke, by Edmé Guillaume, canon of Auxerre, in 1590. The invention at once proved a success, and the new bass became a valuable addition to church concerted music, more especially in France, in spite of the serpent's harsh, unpleasant tone. Mersenne (1636) describes and figures the serpent of his day in detail, but it was evidently unknown to Praetorius (1618). During the 18th century the construction of the instrument underwent many improvements, the tendency being to make the unwieldy windings more compact. At the beginning of the 19th century the open holes had been discarded, and as many as fourteen or seventeen keys disposed conveniently along the tube. Gerber, in his Lexikon (1790), states that in 1780 a musician of Lille, named Régibo, making further experiments on the serpent, produced a bass horn, giving it the shape of the bassoon for greater portability; and Frichot, a French refugee in London, introduced a variant of brass which rapidly won favour under the name of “bass horn” or “basson russe” in English military bands. On being introduced on the continent of Europe, this instrument was received into general use and gave a fresh impetus to experiments with basses for military bands, which resulted first in the ophicleide (q.v.) and ultimately in the valuable invention of the piston or valve.

Further information as to the technique and construction of the serpent may be gained from Joseph Fröhlich's excellent treatise on all the instruments of the orchestra in his day (Bonn, 1811), where clear and accurate practical drawings of the instruments are given. (K. S.)

SERPENTARIUS, or Ophiuchus, in astronomy, a constellation of the northern hemisphere, anciently named Aesculapius, and mentioned by Eudoxus (4th century B.C.) and Aratus (3rd century B.C.). According to the Greek fables it variously represents: Carnabon (or Charnabon), king of the Getae, killing one of the dragons of Triptolemus, or Heracles killing the serpent at the river Sangarius (or Sagaris), or the physician Asclepius (Aesculapius), to denote his skill in curing snake bites. Ptolemy catalogued 29 stars, Tycho Brahe 15, and Hevelius 40. “New” stars were observed in 1604 and 1848.

SERPENTINE, in geometry, a cubic curve described by Sir

Isaac Newton, and given by the cartesian equation

y(a2 + x2) = abx.

The origin is a point of inflection,

the axis of x is an asymptote, and the

curve lies between the parallel lines

2y = ±b.

The origin is a point of inflection,

the axis of x is an asymptote, and the

curve lies between the parallel lines

2y = ±b.

SERPENTINE, a mineral which, in a massive and impure form, occurs on a large scale as a rock, and being commonly of variegated colour, is often cut and polished, like marble, for use as a decorative stone. It is generally held that the name was suggested by the fancied resemblance of the dark mottled green stone to the skin of a serpent, but it may possibly refer to some reputed virtue of the stone as a cure for snake-bite. Serpentine was probably, at least in part, the λίθος ὀφίτης of Dioscorides and the ophites of Pliny; and this name appears in a latinized form as the serpentaria of G. Agricola, writing in the 16th century, and as the lapis serpentinus and marmor serpentinum of other early writers. Italian sculptors have sometimes termed it ranochia in allusion to its resemblance to the skin of a frog.

Although popularly called a “marble,” serpentine is essentially different from any kind of limestone, in that it is a magnesium silicate, associated however, with more or less ferrous silicate. Analyses show that the mineral contains H4Mg3Si2O9, and if the water be regarded as constitutional the formula may be written Mg2(SiO4)2H3(MgOH). Serpentine occurs massive, fibrous, lamellar or granular, but never crystallized. Fine pseudomorphs having the form of olivine, but the composition of serpentine, are known from Snarum in Buskerud, Norway, the crystals revealing their character by containing an occasional kernel of the original mineral. The alteration of rocks rich in olivine has given rise to much of the serpentine occurring as rock-masses (see Peridotite). Studied microscopically, the change is seen to proceed from the surface and from the irregular cracks of the olivine, producing fibres of serpentine. The iron of the olivine passes more or less completely into the ferric state, giving rise to grains of magnetite, which form a black dust, and may ultimately yield scales of haematite or limonite. Considerable increase of volume generally accompanies serpentinization, and thus are produced fissures which afford passage for the agents of alteration, resulting in the formation of an irregular mesh-like structure, formed of strings of serpentine enclosing kernels of olivine in the meshes, and this olivine may itself ultimately become serpentinized. Serpentine may also be formed by the alteration of other non-aluminous ferro-magnesian silicates such as enstatite, augite or hornblende, and in such cases it may show microscopically a characteristic structure related to the cleavage of the original mineral, notably lozenge-shaped in the case of hornblende. Many interesting pseudomorphs of serpentine were described by Professor J. D. Dana from the Tilly Foster iron-mine, near Brewster, New York, U.S.A., including some remarkable specimens with cubic cleavage.

The purest kind of serpentine, known as “noble serpentine,” is generally of pale greenish or yellow colour, slightly translucent, and breaking with a rather bright conchoidal fracture. It occurs chiefly in granular limestone, and is often accompanied by forsterite, olivine or chondrodite. The hardness of serpentine is between 3 and 4, while the specific gravity varies from 2.5 to 2.65. A green serpentine of the exceptional hardness of 6,

- ↑ See Mémoire concernant l'histoire ecclésiastique et civile d'Auxerre (Paris. 1848), ii. 189.