fossiliferous of these occurring in Asturias. The Lower Carboniferous rocks of Spain consist partly of limestones, and partly of shales,

sandstones and conglomerates like the culm of Devonshire. It is

in the culm of the province of Huelva that the celebrated copper

mines of Rio Tinto are worked. The Upper Carboniferous is formed

to a large extent of sandstones and shales, with seams of coal; but

beds of massive limestones are often intercalated, and some of these

contain Fusulina and other fossils like those of the Russian Fusulina

limestone. The system is most extensively developed in the north,

covering a considerable space in Asturias, whence it stretches more

or less continuously through the provinces of Leon, Palencia and

Santander. Another tract, about 500 sq. kilometres in extent, runs

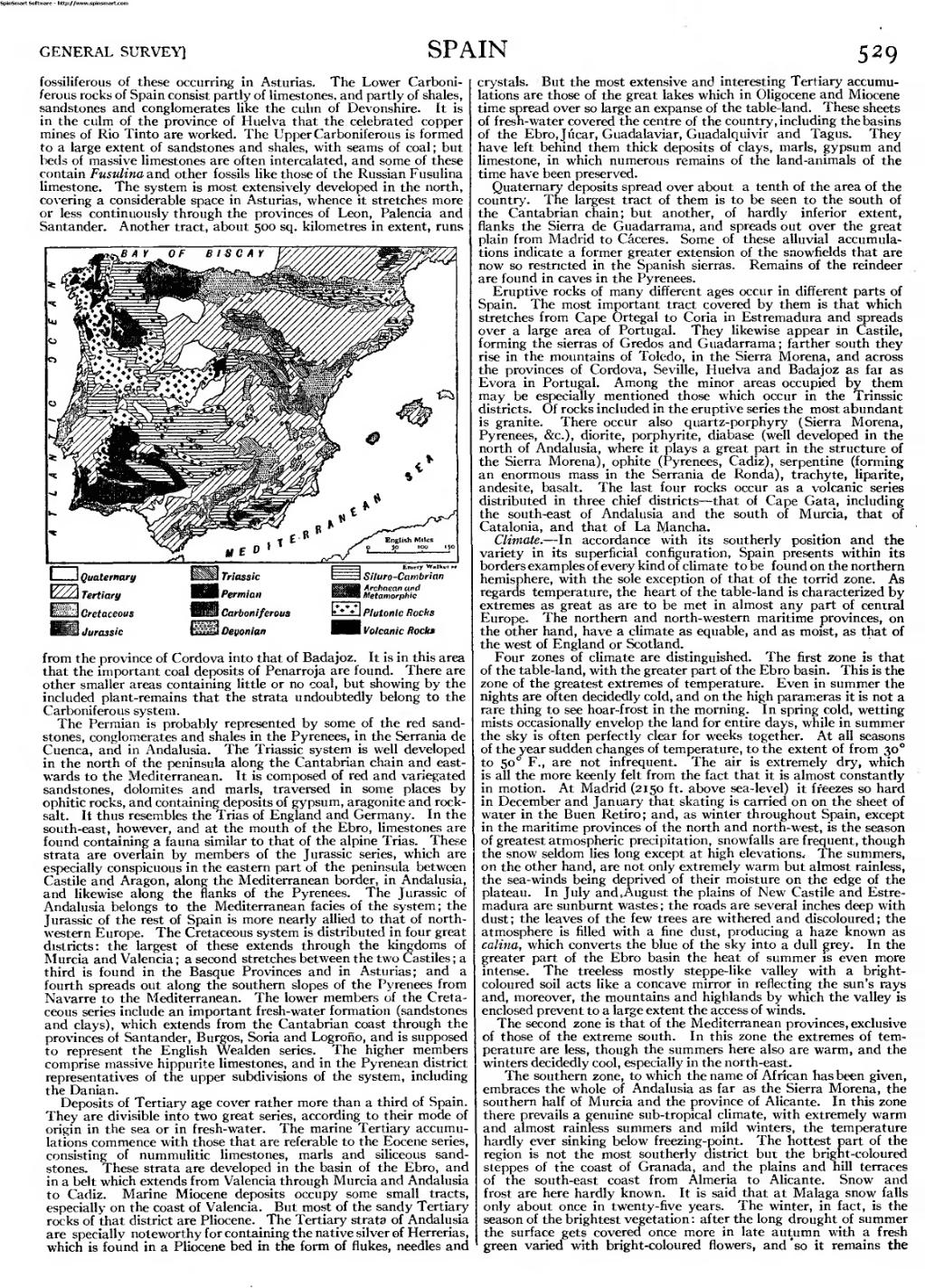

from the province of Cordova into that of Badajoz. It is in this area that the important coal deposits of Penarroja are found. There are other smaller areas containing little or no coal, but showing by the included plant-remains that the strata undoubtedly belong to the Carboniferous system.

The Permian is probably represented by some of the red sandstones, conglomerates and shales in the Pyrenees, in the Serrania de Cuenca, and in Andalusia. The Triassic system is well developed in the north of the peninsula along the Cantabrian chain and eastwards to the Mediterranean. It is composed of red and variegated sandstones, dolomites and marls, traversed in some places by ophitic rocks, and containing deposits of gypsum, aragonite and rock-salt. It thus resembles the Trias of England and Germany. In the south-east, however, and at the mouth of the Ebro, limestones are found containing a fauna similar to that of the alpine Trias. These strata are overlain by members of the Jurassic series, which are especially conspicuous in the eastern part of the peninsula between Castile and Aragon, along the Mediterranean border, in Andalusia, and likewise along the flanks of the Pyrenees. The Jurassic of Andalusia belongs to the Mediterranean facies of the system; the Jurassic of the rest of Spain is more nearly allied to that of north-western Europe. The Cretaceous system is distributed in four great districts: the largest of these extends through the kingdoms of Murcia and Valencia; a second stretches between the two Castiles; a third is found in the Basque Provinces and in Asturias; and a fourth spreads out along the southern slopes of the Pyrenees from Navarre to the Mediterranean. The lower members of the Cretaceous series include an important fresh-water formation (sandstones and clays), which extends from the Cantabrian coast through the provinces of Santander, Burgos, Soria and Logroñio, and is supposed to represent the English Wealden series. The higher members comprise massive hippuriie limestones, and in the Pyrenean district representatives of the upper subdivisions of the system, including the Danian.

Deposits of Tertiary age cover rather more than a third of Spain. They are divisible into two great series, according to their mode of origin in the sea or in fresh-water. The marine Tertiary accumulations commence with those that are referable to the Eocene series, consisting of nummulitic limestones, marls and siliceous sandstones. These strata are developed in the basin of the Ebro, and in a belt which extends from Valencia through Murcia and Andalusia to Cadiz. Marine Miocene deposits occupy some small tracts, especially on the coast of Valencia. But most of the sandy Tertiary rocks of that district are Pliocene. The Tertiary strata of Andalusia are specially noteworthy for containing the native silver of Herrerias, which is found in a Pliocene bed in the form of flukes, needles and crystals. But the most extensive and interesting Tertiary accumulations are those of the great lakes which in Oligocene and Miocene time spread over so large an expanse of the table-land. These sheets of fresh-water covered the centre of the country, including the basins of the Ebro, Júcar, Guadalaviar, Guadalquivir and Tagus. They have left behind them thick deposits of clays, marls, gypsum and limestone, in which numerous remains of the land-animals of the time have been preserved.

Quaternary deposits spread over about a tenth of the area of the country. The largest tract of them is to be seen to the south of the Cantabrian chain; but another, of hardly inferior extent, flanks the Sierra de Guadarrama, and spreads out over the great plain from Madrid to Cáceres. Some of these alluvial accumulations indicate a former greater extension of the snowfields that are now so restricted in the Spanish sierras. Remains of the reindeer are found in caves in the Pyrenees.

Eruptive rocks of many different ages occur in different parts of Spain. The most important tract covered by them is that which stretches from Cape Ortegal to Coria in Estremadura and spreads over a large area of Portugal. They likewise appear in Castile, forming the sierras of Gredos and Guadarrama; farther south they rise in the mountains of Toledo, in the Sierra Morena, and across the provinces of Cordova, Seville, Huelva and Badajoz as far as Evora in Portugal. Among the minor areas occupied by them may be especially mentioned those which occur in the Triassic districts. Of rocks included in the eruptive series the most abundant is granite. There occur also quartz-porphyry (Sierra Morena, Pyrenees, &c.), diorite, porphyrite, diabase (well developed in the north of Andalusia, where it plays a great part in the structure of the Sierra Morena), ophite (Pyrenees, Cadiz), serpentine (forming an enormous mass in the Serrania de Ronda), trachyte, liparite, andesite, basalt. The last four rocks occur as a volcanic series distributed in three chief districts—that of Cape Gata, including the south-east of Andalusia and the south of Murcia, that of Catalonia, and that of La Mancha.

Climate.—In accordance with its southerly position and the variety in its superficial configuration, Spain presents within its borders examples of every kind of climate to be found on the northern hemisphere, with the sole exception of that of the torrid zone. As regards temperature, the heart of the table-land is characterized by extremes as great as are to be met in almost any part of central Europe. The northern and north-western maritime provinces, on the other hand, have a climate as equable, and as moist, as that of the west of England or Scotland.

Four zones of climate are distinguished. The first zone is that of the table-land, with the greater part of the Ebro basin. This is the zone of the greatest extremes of temperature. Even in summer the nights are often decidedly cold, and on the high parameras it is not a rare thing to see hoar-frost in the morning. In spring cold, wetting mists occasionally envelop the land for entire days, while in summer the sky is often perfectly clear for weeks together. At all seasons of the year sudden changes of temperature, to the extent of from 30 to 50 F., are not infrequent. The air is extremely dry, which is all the more keenly felt from the fact that it is almost constantly in motion. At Madrid (2150 ft. above sea-level) it freezes so hard in December and January that skating is carried on on the sheet of water in the Buen Retiro; and, as winter throughout Spain, except in the maritime provinces of the north and north-west, is the season of greatest atmospheric precipitation, snowfalls are frequent, though the snow seldom lies long except at high elevations. The summers, on the other hand, are not only extremely warm but almost rainless, the sea-winds being deprived of their moisture on the edge of the plateau. In July and .August the plains of New Castile and Estremadura are sunburnt wastes; the roads are several inches deep with dust; the leaves of the few trees are withered and discoloured; the atmosphere is filled with a fine dust, producing a haze known as calina, which converts the blue of the sky into a dull grey. In the greater part of the Ebro basin the heat of summer is even more intense. The treeless mostly steppe-like valley with a bright-coloured soil acts like a concave mirror in reflecting the sun's rays and, moreover, the mountains and highlands by which the valley is enclosed prevent to a large extent the access of winds.

The second zone is that of the Mediterranean provinces, exclusive of those of the extreme south. In this zone the extremes of temperature are less, though the summers here also are warm, and the winters decidedly cool, especially in the north-east.

The southern zone, to which the name of African has been given, embraces the whole of Andalusia as far as the Sierra Morena, the southern half of Murcia and the province of Alicante. In this zone there prevails a genuine sub-tropical climate, with extremely warm and almost rainless summers and mild winters, the temperature hardly ever sinking below freezing-point. The hottest part of the region is not the most southerly district but the bright-coloured steppes of the coast of Granada, and the plains and hill terraces of the south-east coast from Almeria to Alicante. Snow and frost are here hardly known. It is said that at Malaga snow falls only about once in twenty-five years. The winter, in fact, is the season of the brightest vegetation: after the long drought of summer the surface gets covered once more in late autumn with a fresh green varied with bright-coloured flowers, and so it remains the