The Man Who Died Twice

By Frank Belknap Long, Jr.

In Death as

in Life Hazlitt

was futile,

spineless, in-

effectual.

Then came

one glorious

opportunity

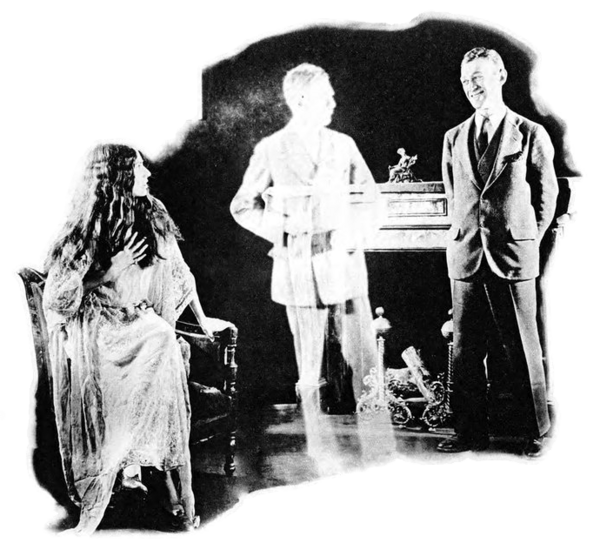

"Something has come between us,” said Hazlitt’s wife, "I feel it like a physical presence.”

When Hazlitt saw the stranger at his desk his emotions were distinctly unpleasant. “Upcher might have given me notice,” he thought. “He wouldn’t have been so high-handed a few months ago!”

He gazed angrily about the office. No one seemed aware of his presence. The man who had taken his desk, was dictating a letter, and the stenographer did not even raise her eyes. “It’s damnable!” said Hazlitt, and he spoke loud enough for the usurper to hear; but the latter continued to dictate: “The premium on policy 6284 has been so long overdue”

Hazlitt stalked furiously across the office and stepped into a room blazing with light and clamorous with conversation. Upcher, the President, was in conference, but Hazlitt ignored the three directors who sat puffing contentedly on fat cigars, and addressed himself directly to the man at the head of the table.

“I’ve worked for you for twenty years,” he shouted furiously, “and you needn’t think you can dish me now. I’ve helped make this company. If necessary, I shall take legal steps”

Mr. Upcher was stout and stern. His narrow skull and small eyes under heavy eyebrows, suggested a very primitive type. He had stopped talking and was staring directly at Hazlitt. His gaze was icily indifferent—stony, remote. His calm was so unexpected that it frightened Hazlitt.

The directors seemed perplexed. Two of them had stopped smoking, and the third was passing his hand rapidly back and forth across his forehead. “I’ve frightened them,” thought Hazlitt. “They know the old man owes everything to me. I mustn’t appear too submissive.”

“You can’t dispose of me like this,” he continued dogmatically. “I’ve never complained of the miserable salary you gave me, but you can’t throw me into the street without notice.”

The President colored slightly. “Our business is very important” he began.

Hazlitt cut him short with a wave of his hand. “My business is the only thing that matters now. . . . I want you to know that I won’t stand for your ruthless tactics. When a man has slaved as I have for twenty years he deserves some consideration. I am merely asking for justice. In heaven’s name, why don’t you say something? Do you want me to do all of the talking?”

Mr. Upcher wiped away with his coat sleeve the small beads of sweat that had accumulated above his collar. His gaze remained curiously impersonal, and when Hazlitt swore at him he wet his lips and began: “Our business is very important”

Hazlitt trembled at the repetition of the man’s unctuous remark. He found himself reluctant to say more, but his anger continued to mount. He advanced threateningly to the head of the table and glared into the impassive eyes of his former employer. Finally he broke out: "You’re a damn scoundrel!”

One of the directors coughed. A sickly grin spread itself across Mr. Upcher's stolid countenance. “Our business, as I was saying”

Hazlitt raised his fist and struck the president of the Richbank Life Insurance Company squarely upon the jaw. It was an intolerably ridiculous thing to do, but Hazlitt was no longer capable of verbal persuasion. And he had decided that nothing less than a blow would be adequate.

The grin disappeared from Mr. Upcher’s face. He raised his right hand and passed it rapidly over his chin. A flash of anger appeared for a moment in his small, deep-set eyes. "Something I don’t understand,” he murmured. "It hurt like the devil. I don’t know precisely what it means!”

"Don’t you?” shouted Hazlitt. "You’re lucky to get off with that. I’ve a good mind to hit you again.” But he was frightened at his own violence, and he was unable to understand why the directors had not seized him. They seemed utterly unaware of anything out of the ordinary: and even Mr. Upcher did not seem greatly upset. He continued to rub his chin, but the old indifference had crept back into his eyes.

"Our business is very important” he began.

Hazlitt broke down and wept. He leaned against the wall while great sobs convulsed his body. Anger and abuse he could have faced, but Mr. Upcher’s stony indifference robbed him of manhood. It was impossible to argue with a man who refused to be insulted. Hazlitt had reached the end of his rope: he was decisively beaten. But even his acknowledgment of defeat passed unnoticed. The directors were discussing policies and premiums and first mortgages, and Mr. Upcher advanced a few commonplace opinions while his right hand continued to caress his chin.

“Policies that have been carried for more than fifty years,” he was saying, “are not subject to the new law. It is possible by the contemplated”

Hazlitt did not wait for him to finish. Sobbing hysterically he passed into the outer office, and several minutes later he was descending in the elevator to the street. All moral courage had left him; he felt like a man who has returned from the grave. He was white to the lips, and when he stopped for a moment in the vestibule he was horrified at the way an old woman poked at him with her umbrella and actually pushed him aside.

The glitter and chaos of Broadway at dusk did not soothe him. He walked despondently, with his hands in his pockets and his eyes upon the ground. "I’ll never get another job.” he thought. "I’m a nervous wreck and old Upcher will never recommend me. I don't know how I’ll break the news to Helen.”

The thought of his wife appalled him. He knew that she would despise him. "She’ll think I’m a jellyfish,” he groaned. "But I did all a man could. You can’t buck up against a stone wall. I can see that old Upcher had it in for me from the start. I hope he chokes!”

He crossed the street at 73rd Street and started leisurely westward. It was growing dark and he stopped for a moment to look at his watch. His hands trembled and the timepiece almost fell to the sidewalk. With an oath he replaced it in his vest. “Dinner will be cold,” he muttered. “And Helen won’t be in a pleasant mood. How on earth am I going to break the news to her?”

When he reached his apartment he was shivering. He sustained himself by tugging at the ends of his mustache and whistling apologetically. He was overcome with shame and fear but something urged him not to put off ringing the bell.

He pressed the buzzer firmly, but no reassuring click answered him. Yet—suddenly he found himself in his own apartment. “I certainly got in,” he mumbled in an immeasurably frightened voice, "but I apparently didn’t come