"the central habitation." The Greeks made Olympus the centre; the Egyptians, Thebes; the Assyrians, Babylon; the Hebrews, Jerusalem; while the Chinese always called their country the central empire. This is natural enough (as Aristotle would say), because most people regard their neighborhood as the centre of the universe, and the number of central railroads shows the continued force of this geometric idea.

One of the most primitive ideas concerning the earth represented it as a vast plain or flat island, surrounded on all sides by an inaccessible and interminable ocean. At the extremities and around the borders were placed the "fortunate isles," or imaginary regions, peopled by giants, pygmies, and extraordinary beings. The circumscribing

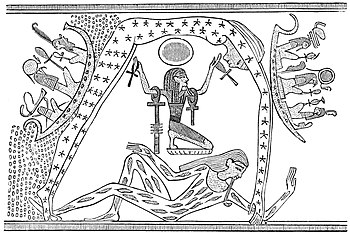

Fig. 7.—Egyptian Representation of the Heavens and Earth.

water surrounding the irregular outlines of the land led to the idea of a universal ocean. But, when men began to have experience of the sea by early navigation, the idea of a circular horizon always observed led to the notion that the ocean was bounded, and the whole earth came to be represented as contained in a circle, beneath which were roots reaching downward without end.

The priests of Veda, the scriptures of Buddhism, asserted that the earth was supported on twelve columns, which they very ingeniously turned to their own account by asserting that these columns were sustained by virtue of the sacrifices that were made to the gods, so that if these were not made the earth would collapse.

"These pillars were invented in order to account for the passing of the sun beneath the earth after his setting, for which at first they