in such districts. Its great economical advantage over animal power, its freedom from liability to become disabled by epizoötic diseases, its reliability under all circumstances, and the many other advantages which are possessed by the machine, are already securing its introduction, despite the difficulties arising from popular prejudice and unfamiliarity, from hostile municipal laws and other existing obstacles.

We are learning that this motor, when it can be used at all, is comparatively inexpensive; that our roads are improved by it; and that the ancient idea of its conflicting with the interests of owners and workers of horses is only a superstition.

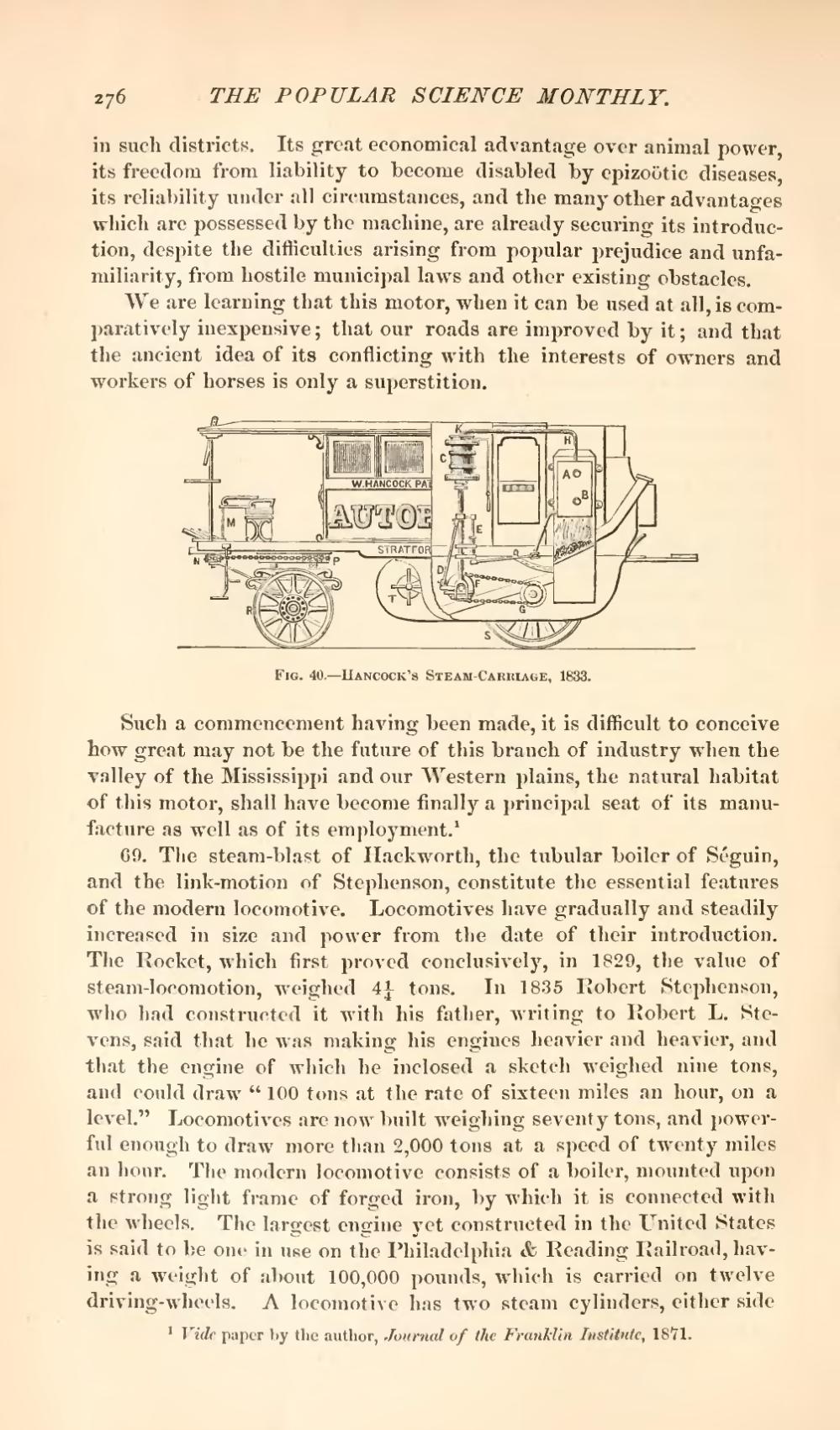

Fig. 40.—Hancock's Steam-Carriage, 1833.

Such a commencement having been made, it is difficult to conceive how great may not be the future of this branch of industry when the valley of the Mississippi and our Western plains, the natural habitat of this motor, shall have become finally a principal seat of its manufacture as well as of its employment.[1]

69. The steam-blast of Hackworth, the tubular boiler of Séguin, and the link-motion of Stephenson, constitute the essential features of the modern locomotive. Locomotives have gradually and steadily increased in size and power from the date of their introduction. The Rocket, which first proved conclusively, in 1829, the value of steam-locomotion, weighed 4¼ tons. In 1835 Robert Stephenson, who had constructed it with his father, writing to Robert L. Stevens, said that he was making his engines heavier and heavier, and that the engine of which he inclosed a sketch weighed nine tons, and could draw "100 tons at the rate of sixteen miles an hour, on a level." Locomotives are now built weighing seventy tons, and powerful enough to draw more than 2,000 tons at a speed of twenty miles an hour. The modern locomotive consists of a boiler, mounted upon a strong light frame of forged iron, by which it is connected with the wheels. The largest engine yet constructed in the United States is said to be one in use on the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, having a weight of about 100,000 pounds, which is carried on twelve driving-wheels. A locomotive has two steam cylinders, either side

- ↑ Vide paper by the author, Journal of the Franklin Institute, 1871.