fore been given to the construction of such an apparatus, termed a regenerator. This has taken various forms in different machines—from a number of simple perforated plates to nests of tubes. Practically it has been found most economical to attempt to abstract only a part of the heat, as to do more offers too great an obstruction to the passage of the air, with the result of losing as much in power as is gained in heat.

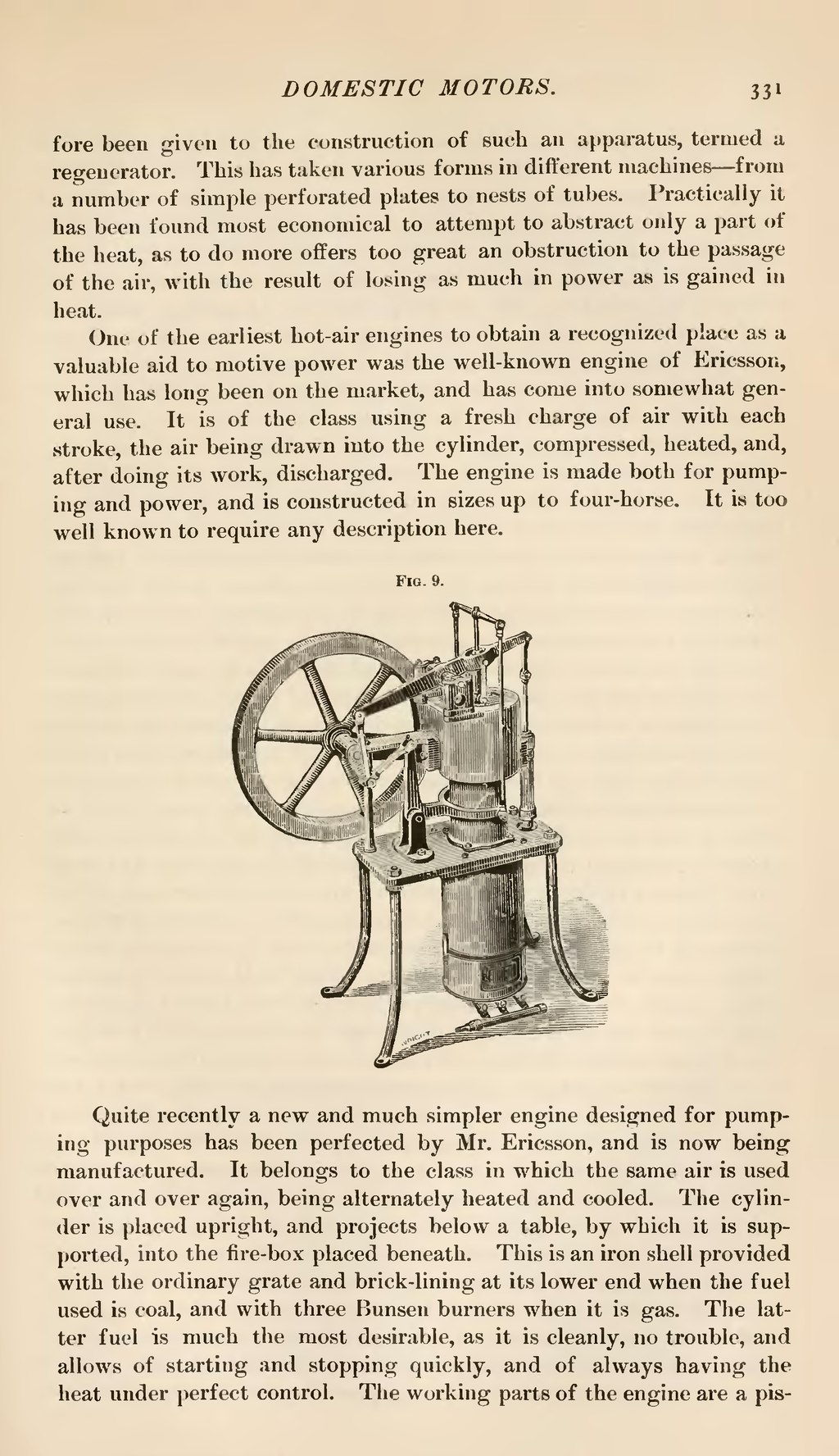

One of the earliest hot-air engines to obtain a recognized place as a valuable aid to motive power was the well-known engine of Ericsson, which has long been on the market, and has come into somewhat general use. It is of the class using a fresh charge of air with each stroke, the air being drawn into the cylinder, compressed, heated, and, after doing its work, discharged. The engine is made both for pumping and power, and is constructed in sizes up to four-horse. It is too well known to require any description here.

Fig. 9.

Quite recently a new and much simpler engine designed for pumping purposes has been perfected by Mr. Ericsson, and is now being manufactured. It belongs to the class in which the same air is used over and over again, being alternately heated and cooled. The cylinder is placed upright, and projects below a table, by which it is supported, into the fire-box placed beneath. This is an iron shell provided with the ordinary grate and brick-lining at its lower end when the fuel used is coal, and with three Bunsen burners when it is gas. The latter fuel is much the most desirable, as it is cleanly, no trouble, and allows of starting and stopping quickly, and of always having the heat under perfect control. The working parts of the engine are a pis-