Taste

we know little that is definite. What little there is points to the lower temporal regions again. Consult Ferrier as below.

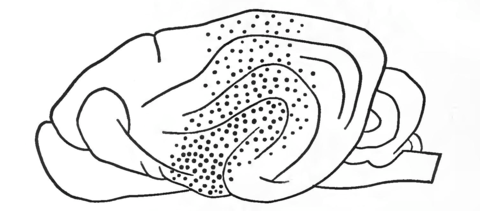

Fig. 19.—Luciani's Olfactory Region in the Dog.

Touch.

Interesting problems arise with regard to the seat of tactile and muscular sensibility. Hitzig, whose experiments on dogs' brains fifteen years ago opened the entire subject which we are discussing, ascribed the disorders of motility observed after ablations of the motor region to a loss of what he called muscular consciousness. The animals do not notice eccentric positions of their limbs, will stand with their legs crossed, with the affected paw resting on its back or hanging over a table's edge, etc.; and do not resist our bending and stretching of it as they resist with the unaffected paw. Goltz, Munk, Schiff, Herzen, and others promptly ascertained an equal defect of cutaneous sensibility to pain, touch, and cold. The paw is not withdrawn when pinched, remains standing in cold water, etc. Farrier meanwhile denied that there was any true anæsthesia produced by ablations in the motor zone, and explains the appearance of it as an effect of the sluggish motor responses of the affected side.[1] Munk[2] and Schiff[3], on the