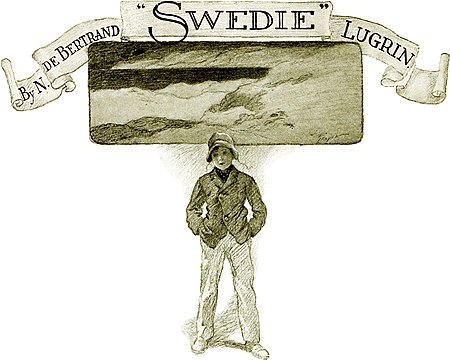

Outside the wind was blowing wailingly about the little cabin, not harshly or loudly, but sobbingly, plaintively, like a child in trouble, and in the lulls the Malemutes took up the mournful cry, sending it out and over the frozen river to the ghostly banks on the other side, that returned it across the ice in a dying whisper. Outside the full moon shone over a world of whiteness. All unbroken lay the snow upon the Yukon, and the pines on the hills, like mute white hands, pointed above to a vault of gleaming stars. By and by the weeping wind, afraid of its own voice, perhaps, died away altogether, and the Malemutes, missing it, and growing tired, ended their wailing also. It was very still, with the stillness of intense cold, and every one in Fortymile was sleeping, for it was past midnight; every one with the exception of “Swedie.”

Inside the little cabin a fire burned fiercely in the heater, and on the coonskin-covered couch beside it little Swedie sat with Viking, his Great Dane dog, and he talked to him in the tongue the boy loved, but alas! could use so seldom now, since his mother’s death, and since he had started to go to school. It was at school that they had given him his name, half in fun, half in contempt. His real name was Eric Gustavus Kalmar, but no one except his father and the schoolmaster paid any attention to that. The school-children had dubbed Eric a bit of a coward, wherein they made a great mistake, though they are no wiser than many older people who cannot tell the difference between proud sensitiveness and silly, shrinking timidity. Swedie had as brave a heart as any of the other little Yukon boys, but because they misjudged him he scorned to show them otherwise, and because he could only speak their language in a halting, nervous way he kept much to himself. If he had been at home in Norway with his own little people, he would have led them all in sport and in his classes as well. But here he felt himself an alien, almost an outcast; and it hurt him all the more because he hid the hurt beneath his proud little exterior, and carried his curly head high,even when the red mantled his cheek in a cruelly hot flush at bearing the laughter at his many mistakes.

And now the rink had been opened, and of all the boys in Fortymile Swedie was the only one who had not been inside. Not because he could not skate,—for two years ago, in Norway, he had won a medal in the boys’ contest,— but because his father had been very unfortunate in his mining ventures, and his mother’s illness had swallowed up all the little capital, so that now every two-bit piece had to be saved. There was scarcely enough money to procure necessities, and Swedie was forced to go without his skates. Since his mother’s death, a year ago, his father had earned a slender living by hunting. He was away just now, and that was why Swedie was awake and talking to Viking. He always worried when his father was absent, for the cold had affected his father’s eyes, and he could net see as well as a hunter should see to be successful, But their wants were few, and Swedie baked the bread and did the washing,422