cannonade from the splendid guns of the expeditionary force. The Chinese replied with spirit, and it was soon apparent that the Allies were not to have an easy victory. One of the principal magazines in the fort was exploded by a shell and yet the Chinese gunners fought on. A series of attempts made to scale the wall of the fort were baffled with heavy loss to the Allies. At length by a happy chance the British discovered a drawbridge, and by cutting the ropes which held it up they secured for the attacking party an easy means of access. The Chinese fought to the last and it was computed that out of a garrison of five hundred but one hundred escaped. On the side of the Allies the losses were considerable: the British alone had 22 killed and 179 wounded. The engagement, however, was a decisive one. Four other forts on the northern side were captured without loss, and the southern forts surrendered without a shot being fired. It only remained for the positions to be formally occupied on August 22nd simultaneously with the entrance of the fleet into the river.

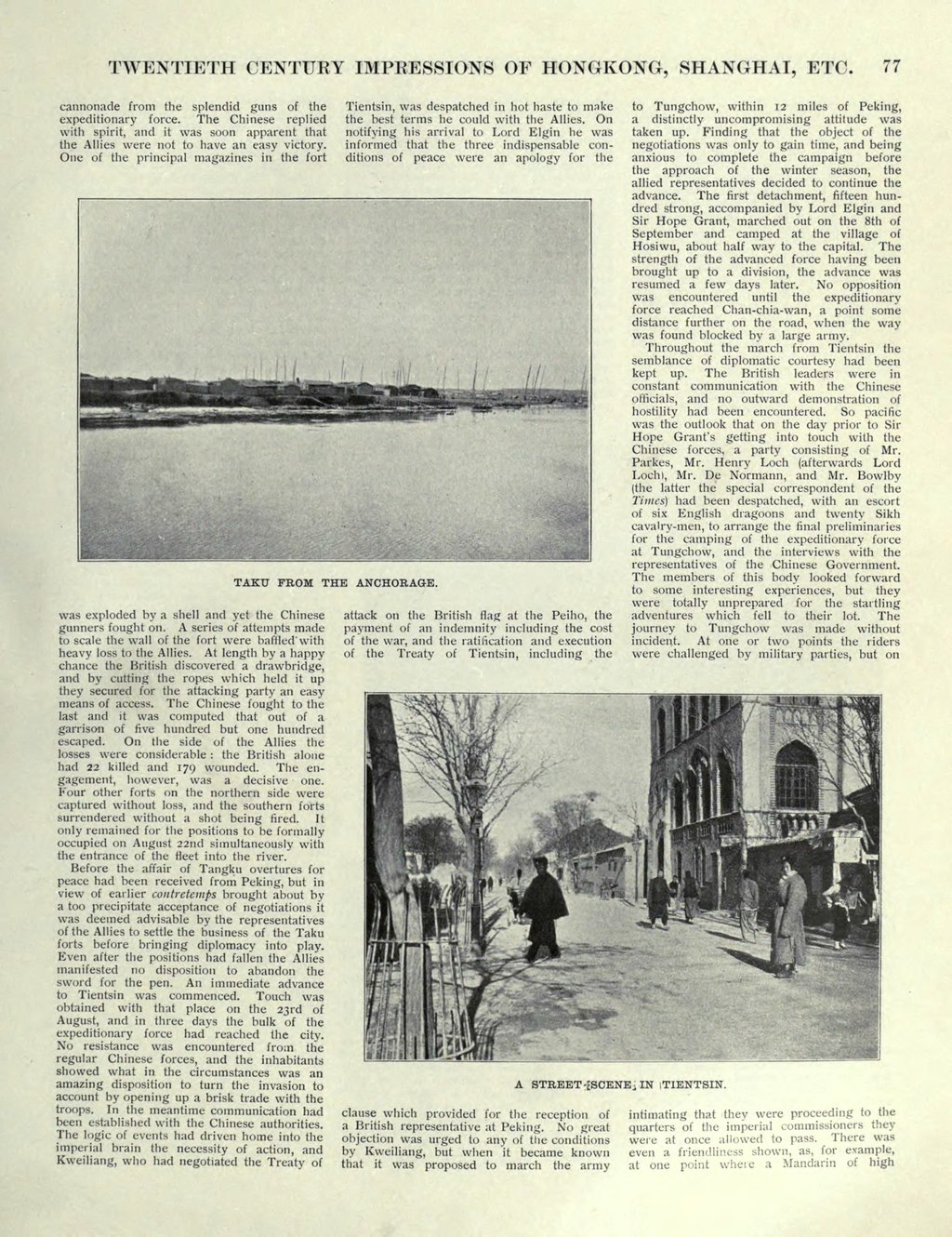

Before the affair of Tangku overtures for peace had been received from Peking, but in view of earlier contretemps brought about by a too precipitate acceptance of negotiations it was deemed advisable by the representatives of the Allies to settle the business of the Taku forts before bringing diplomacy into play. Even after the positions had fallen the Allies manifested no disposition to abandon the sword for the pen. An immediate advance to Tientsin was commenced. Touch was obtained with that place on the 23rd of August, and in three days the bulk of the expeditionary force had reached the city. No resistance was encountered from the regular Chinese forces, and the inhabitants showed what in the circumstances was an amazing disposition to turn the invasion to account by opening up a brisk trade with the troops. In the meantime communication had been established with the Chinese authorities. The logic of events had driven home into the imperial brain the necessity of action, and Kweiliang, who had negotiated the Treaty of Tientsin, was despatched in hot haste to make the best terms he could with the Allies. On notifying his arrival to Lord Elgin he was informed that the three indispensable conditions of peace were an apology for the attack on the British flag at the Peiho, the payment of an indemnity including the cost of the war, and the ratification and execution of the Treaty of Tientsin, including the clause which provided for the reception of a British representative at Peking. No great objection was urged to any of the conditions by Kweiliang, but when it became known that it was proposed to march the army to Tungchow, within 12 miles of Peking, a distinctly uncompromising attitude was taken up. Finding that the object of the negotiations was only to gain time, and being anxious to complete the campaign before the approach of the winter season, the allied representatives decided to continue the advance. The first detachment, fifteen hundred strong, accompanied by Lord Elgin and Sir Hope Grant, marched out on the 8th of September and camped at the village of Hosiwu, about half way to the capital. The strength of the advanced force having been brought up to a division, the advance was resumed a few days later. No opposition was encountered until the expeditionary force reached Chan-chia-wan, a point some distance further on the road, when the way was found blocked by a large army.

Throughout the march from Tientsin the semblance of diplomatic courtesy had been kept up. The British leaders were in constant communication with the Chinese officials, and no outward demonstration of hostility had been encountered. So pacific was the outlook that on the day prior to Sir Hope Grant's getting into touch with the Chinese forces, a party consisting of Mr. Parkes, Mr. Henry Loch (afterwards Lord Loch), Mr. De Normann, and Mr. Bowlby (the latter the special correspondent of the Times) had been despatched, with an escort of six English dragoons and twenty Sikh cavalry-men, to arrange the final preliminaries for the camping of the expeditionary force at Tungchow, and the interviews with the representatives of the Chinese Government. The members of this body looked forward to some interesting experiences, but they were totally unprepared for the startling adventures which fell to their lot. The journey to Tungchow was made without incident. At one or two points the riders were challenged by military parties, but on intimating that they were proceeding to the quarters of the imperial commissioners they were at once allowed to pass. There was even a friendliness shown, as, for example, at one point where a Mandarin of high