CHAPTER II

Characteristics of the New Zealanders—Former Cannibals who have become Good Citizens

And now what can be said of them who have created this meritorious State? Are they, because they have accomplished so much in so brief a time, an extraordinary people; are they mentally, morally, socially superior, as individuals? In one respect, perhaps, the New Zealanders differ from the majority of mankind. As a democracy they have made more of their opportunities. They have run where others walked or wallowed. They have exhibited humanitarianism where others displayed brutality, uncharitableness, or indifference.

New Zealanders are so far from being extraordinary that they have been called parochial and conceited. On criticism laudatory of their country they smile, and, some charge, on censure frown. Many parochial and conceited New Zealanders there are, but I cannot candidly say that the average New Zealander is more parochial or conceited than are millions of people in the United States or in Europe. On subjects affecting his native heath the New Zealander undoubtedly is sensitive, but what nationalities are not so?

On the other hand, prolonged prosperity apparently has created in the New Zealander some indifference to criticism which, if heeded, might have beneficial results. It is possible that, for the development of character, New Zealand has had too much prosperity.

World-wide praise also has contributed to the New Zealander's self-complacency. With the world's eyes upon him, he sometimes proudly asks the visitor, "What do you think of our little country?" But his national pride is excusable. His land has accomplished something worthy. It has labored to alleviate the burdens of the commonalty; it has set the world a bright example.

New Zealanders are a busy, independent, and pleasure-loving people. Their popular sports are horse-racing, football, cricket, tennis, golf, swimming, and yachting. In every part of the country there is a weekly half-holiday for factories, shops, offices, the building trades, etc., and in addition there are from six to seven full holidays each year. Proof that New Zealanders enjoy themselves may be seen on any clement Saturday night, when, in the cities, thousands leisurely stroll the streets, crowding the footpaths and filling the roadways from curb to curb. Noteworthy, too, is the observance of the Sabbath. On that day scarcely a train moves; in some cities street cars do not run during church services; and all shops and hotel bars are closed. To those persons who find the customary fishing expedition or steamer excursion a tame diversion, Sunday in Aotearoa often is most pronouncedly dull.

Another noticeable characteristic of the New Zealander is his friendly feeling toward the United States. One of the stanchest supporters of friendly relations

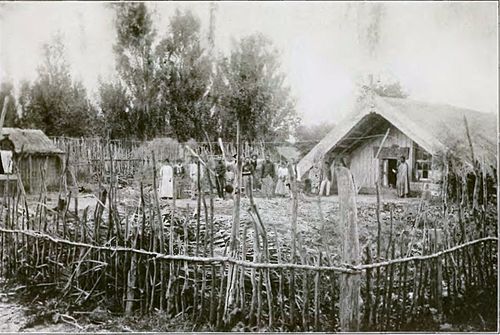

MAORI MEETING HOUSE

with the United States is New Zealand's Chief Justice, Sir Robert Stout. "I have always been of opinion," he told me, "that we ought to have close relations with our kin beyond the sea on the Pacific. This is why I have ever advocated social and trade relations between New Zealand and the United States. And personally I have always liked the Americans I have met."

Apparently one cause of New Zealand's friendliness toward the United States is the fear of an Asiatic armed invasion. At present New Zealand appears to have little reason for such apprehension, yet, as mirrored in the press, it is held to be a possibility of the future. There are now only about three thousand Chinese in the country—much less than formerly—and in the last decade less than one hundred Japanese have entered New Zealand. It is apparent also that an imperial war with Germany has not been overlooked.

A determination to be prepared for war has caused New Zealand, partly at the suggestion of Lord Kitchener, to adopt compulsory military training. This action, though perhaps popular with the majority of New Zealand men, has been received with bitter hostility by thousands of them, and many have preferred prison sentences to enforced service. From all able-bodied males over twelve years of age military training is required until the age of twenty-five, followed by enrollment in the Reserve Force until the age of thirty.

New Zealanders are intelligent; and, answering the American woman who asked, "What language do New Zealanders speak?" they speak English. The country has one of the best public school systems in the world, and eighty-five per cent of its people can both read and write. It has primary, secondary, and high schools, technical and industrial schools, training colleges for teachers, and schools for the Maoris. It has a limited free-book system, various free scholarships, and evening continuation classes. With the exception of fees charged for instruction in the higher branches at district high schools, education in the public schools is free, and, between the ages of seven and fourteen, compulsory.

My prefatory reference to the New Zealanders would be incomplete without an accompanying introduction of the Dominion's romantic brown people. Beneath the ensign of the Southern Cross and the Union Jack dwells a race of imposing stature, almost the tallest among men. Its members, dark-haired, smiling, and robust, are intelligent, in land collectively wealthy, independent, proud, and jealous of their rights.

Such are the New Zealand Maoris, the venturesome sailors of Hawaiki, the greatest fighting people of the South Pacific. A man-eating, blood-drinking race, they yet had their poets, their orators, their astronomers and wise men. Long before Columbus braved the dangers of unknown seas the Maoris roved the wide Pacific. For thousands of miles they pushed outward from the east, west, and north in naught but canoes, discovering and populating many islands, and in New Zealand reaching their ultima Thule. The Maoris have a remarkable history, one rich in stories of the human passions, of love and hate, of merciless warfare, of cannibalism, of multitudinous superstitions and amazing, deadly suspicions. To those who love to delve into the mystic past of primitive people the history of the Maoris is a romance of romances. It carries the investigator from Arabia to America, from Northern India and Hawaii to the pathetic remnants of the Morioris in the Chatham Islands. It involves the rise and fall of nations. It tells of many migrations, of almost constant intertribal warfare. It is replete with tales of gods and demigods, of monsters of land and sea. It is bright with charming recitals of love escapades of man and maiden.

Stirring, indeed, were the days of old. For hundreds of years the militant cry of the toa rang through the land, from Hawke Bay to Taranaki, from Auckland to the greenstone isle. War was waged on a thousand pretexts: over land, women, curses, insults. Until 1869 cannibalism existed, although it had long been uncommon; and as late as 1871 Maoris warred against the colonials.

Whence came the Maoris? From Hawaiki, they say. But where is Hawaiki? There are many Hawaikis. All the myriad islands of Polynesia, from Easter Island to Ponape, from Hawaii to New Zealand, say that Hawaiki, or its equivalent in the various Polynesian dialects, was their original home; but their ideas respecting the exact location of this ancestral abode are somewhat vague. According to S. Percy Smith, at least seven Hawaikis are known, among them Hawaii, Samoa, Tahiti, and neighboring islands, and Rarotonga. Mr. Smith believes the Hawaiki of the Maoris to be Tahiti and adjoining islands. Maoris themselves say that they came from Tawhiti-nui, but it is doubtful if the first Hawaiki was situated in that part of the world.

Tentatively Mr. Smith has traced the Maoris back to India. Judge Pomander, of Hawaii, held that these Polynesians, and Polynesians in general, were a branch of the Indo-Europeans. Other investigators have traced them to Arabia, thus giving them a Caucasian origin. Professor J. Macmillan Brown has traced them to the Mediterranean's shores. By Judge Francis Dart Fenton the Maoris were accorded kinship with the Sabaians, the most celebrated of all the people of ancient Arabia. The Sabaians were "men of stature," says Jeremiah, and one of their rulers was the Queen of Sheba.

The date of the first arrival of the Maoris in New Zealand is not positively known. Judge Fenton says that apparently there were thirteen expeditions to New Zealand of which traditional accounts have been preserved, and others of which only uncertain stories exist. According to Mr. Smith, the original discovery of New Zealand by a Maori was made in the tenth century by Kupe, a high chief of Tahiti. About 1350 A.D. there reached New Zealand a fleet of six double-decked canoes. This is the greatest Maori migration known to-day.

MAORI WARRIOR

If the Hawaiki of the Maoris was Tahiti, it was a long, dreary, and dangerous voyage they were forced to make to reach New Zealand. After leaving Rarotonga, there were about two thousand statute miles of sea to navigate before reaching the northern part of Aotearoa, where nearly all the canoes landed, and there were but a few wide-scattered islands en route, at which the voyagers may or may not have halted.

When the Maoris settled in New Zealand they found it inhabited by a race generally believed, though not absolutely known, to be the Morioris, a branch of the Polynesians. Whatever race it was, it is certain that its members were soon conquered and enslaved, and many of them eaten, by the Maoris. If they were not Morioris, they have been long extinct; if they were, they have been so nearly exterminated that to-day not more than a half-dozen pure-blooded members of the race exist, and all of these live on the Chatham Islands, about five hundred miles east of Lyttleton.

Possibly the people inhabiting New Zealand prior to the Maoris were Melanesians; but the Melanesian taint seen in a few Maoris to-day is not generally regarded as evidence that a black race once lived in the Dominion. Yet one tradition says that Melanesians reached New Zealand in a canoe about 1250 A.D. Probably this relationship to the black is due to intermarriage in Fiji and westward centuries ago.

After establishing themselves in New Zealand the Maoris did not organize any intertribal governments or make any efforts to form a nation. From the first every tribe, with occasional exceptions inspired by policy, lived and fought for itself. Changes of scene, of climate, and the possession of greater chances for development, did not modify the militant propensity of these barefooted colonists. They warred as they did in Hawaiki. Over all the land blood was spilled; whole tribes were destroyed, and cannibal feasts were common. Every able man was a warrior, ready at an instant's notice to exchange the peace of home for the strife of battle-field. On fortified hills the Maori ensconced himself, and there, day and night, watched and waited for his enemies; or, with spear, sword, club, and tomahawk, sallied forth for conquest.

Apparently the Maoris were constantly at war because they loved it, but John White says they did not, "though when once in it they are so proud that they cannot think of wishing or offering terms of peace." Undoubtedly the majority of Maori wars were due to violations of the Maori's code. Possibly no people had a nicer sense of honor, "in the old acceptation of the term," says Gudgeon, than the Maori. To him the slightest insult or injury "was unbearable, and therefore quickly avenged, even when the injured tribe was weak compared with the enemy." A single tribesman could start a war merely by a verbal insult. Even a fancied insult from a child has caused war.

A feature of Maori warfare was cannibalism, the worst stage of which was reached in Hongi's wars. Long prior to this, cannibalism had gratified appetite both in war and peace. This was so generally known to early navigators to New Zealand that for years, the terror of cannibalism prevented intercourse with the natives. In 1780, when in the House of Commons New Zealand was proposed as a suitable place for a convict colony, "the cannibalistic propensities of the natives was urged in opposition and silenced every other argument."

By many Maoris human flesh was classed as the best of all flesh. Some Maoris were so eager for food of this sort that they lay in wait for victims "like the tigers of India." Many of the victims of cannibalism were slaves, some of whom were eaten in peaceful times. One writer says that occasionally even children were eaten. Yet the Maoris liked children so well that they spoiled them. When children were the offspring of an enemy, however, it was considered proper to eat them.

As the Maoris increased in numbers in New Zealand, they spread over the land until, from the North Cape to the Bluff, not an inch of soil remained unclaimed. And all land claims were guarded with the most jealous care. The Maori was always sure of his boundaries. His landmarks were trees, streams, stones, holes, posts, rattraps, and eel-dams. These boundaries were thoroughly memorized. Patiently and minutely their names, location, and characteristics were implanted in the minds of Maori youth by father and grandfather. Instruction also was given in all important history connected with the acquirement and possession of the land. And all these lessons were treasured by the pupil with a memory that, says Judge Fenton, was reliable up to twenty Maori generations, or five hundred years.

A dispute over landmarks among such positive, combative memorizers was sure to lead to serious trouble. That which the Maori regarded as his "mother's milk," and his "life from childhood," he at all times was ready to risk his life to retain. Considering the complex nature of Maori land titles, it is not surprising that there was a multitude of land disputes, or that many land title tangles try the patience of the Native Land Court to-day.

Some of the claims made by native landowners are amazing. One Maori believed he was entitled to a tract of land because he had been cursed on it. Another claimed ownership because he had been injured on the property involved. By the Colonial Government one claim actually was allowed because one of the claimants swore that he had seen a ghost on the disputed land.

The Maoris have always held land in common, and to a very large extent they so hold their five million acres to-day. To them communal ownership seems to be satisfactory, but when a white man leases a piece of their land he may not find the system so agreeable. When the first rent-day arrives he, like the Bay of Plenty physician I heard about, may be harassed by several landlords and landladies.

In answer to a knock one day, this doctor opened his front door to find his veranda occupied by three or four generations of Maoris. What did they want? "Money

A MAORI VILLAGE

for the rent." The lessee did not want to deal with what looked to him like a tribe, and, summoning a frown, he shouted: "Get out of here!" The rent collectors got, but outside the gate they halted, and after a parley they sent back, with better results, one of their number to collect for all.

Among Maoris land was a frequent cause of war, and it was often a bloody bone of contention between them and the white settlers. An early result of the "king movement," culminating in 1858 in the proclamation of Potatau Te Wherowhero as the first Maori king, an act that was prompted partly by a desire to retain native lands in Maori hands, was war. In this thousands of troops, including ten thousand imperial soldiers, were engaged for months. The Maoris displayed great bravery, first-class fighting ability, and remarkable cunning. The end of the war was dramatic, and typical of the Maori spirit.

In a hurriedly built fort about three hundred natives, among them women and children, for three days withstood the artillery and rifle fire and bayonet charges of fifteen hundred soldiers. When called upon to surrender, Rewi, the chief in charge, wrote to General Cameron:—

"Friend, this is the word of the Maori: They will fight on forever, forever, forever."

The women, declining an opportunity to leave the fort in safety, said:—

"If our husbands are to die, we and the children will die with them."

Finally, however, the pa's defenders dashed out in compact formation and scattered for freedom, leaving about half the garrison dead and wounded.

Of men the Maoris never were afraid, but the boldest among them quailed at thoughts of incurring the displeasure of gods and spirits. They still are superstitious, but not to the degree they once were. At all times their lives were regulated by a strict regard for the supernatural. In their memory the respected, dreaded tapu was deeply engraved in large letters. To break it often meant death. From the legendary day that the god Tanemahuta separated earth and heaven by standing on his head and kicking upward, "the whole Maori race, from the child of seven years to the hoary head, were guided in all their actions by omens."

In those days witchcraft was rampant, and persons accused of it were put to death. Curses, which were believed to be the main causes of bewitchery, were so dreaded that whole families were sometimes driven to death merely by the knowledge that they had been cursed. When a Maori believed himself to be bewitched he consulted a priest, or tohunga, who, with much ceremony, including many incantations, tried to destroy the effects of the curse.

The number of objects to which tapu applied among the Maoris was astonishing. This touch not, taste not, handle not perturber was always exercising its baneful influences. Even to those it protected it was dangerous. Also it was inconvenient. The possessors of tapu, according to an authority, did not even dare to carry food on their backs, and everything belonging to them was tapu, or prohibited to the touch or use of others. The suggestions of punishment conveyed by violations of tapu were so strong that sometimes they frightened the culprits to death.

Some forms of tapu were removable by tohungas, as those existing at the baptism of children and at tattooings. It would seem that tohungas—who, often priests, also were wizards, seers, physicians, tattooers and barbers, and not uncommonly builders of houses and canoes—had enough to do merely in lessening and preventing the results of tapu violations; but it was not so. Much of their time was spent as physicians. As such their services were required for ills both real and imaginary. Their cures were effected mainly by suggestion, and to create and convey curative fancies they employed a great variety of invocations. Also they called to their aid the properties of barks, roots, and leaves, supplemented by the planting and waving of twigs, clawing of the air, and bodily contortions. They were surprisingly successful, despite the fact that many of their cures were secured under such rigorous treatment as bathing in cold water to eradicate fever and consumption.

Tohungas did not claim ability to raise the dead, but they did undertake to revive all who were on the verge of the grave, on certain conditions. Then even the stars were required as assisting agencies. The Pleiades had to be at or near their zenith and the morning star must be seen when Toutouwai the robin caroled his first song of the day.

When the patient recovered, the tohunga was a great man. But when the patient died, there was weeping and wailing. Then it was the mournful tangi was held; then men and women came from far and near to condole with the sorrowing, to cry loudly, to feast even while their hearts were heavy and their eyes red with the deluge of many tears. Then were heard wild songs, then were seen frenzied dances, then flowed the blood of lamenting ones, usually women, who in their mad grief slashed their bodies and sometimes their faces. Sacrifices of slaves were occasionally made, that the bewailed might have attendant spirits. Sometimes even suicide was committed, as when the wives of a chief strangled themselves; and sometimes, too, wailing ones fell dead from exhaustion, and in Te Reinga joined those for whom they had so passionately mourned.

The tangi is generally observed among the Maoris even to-day. Still are heard, for days at a time, the moan, the wail, the startling outburst of pent emotion. Still tears flow copiously, noses are rubbed against each other in grievous salutation, and there are collected the great commissariat stores so indispensable where the hangi (oven) is necessary to the prolonged continuance of the tangi.

A modern tangi is a very lamentable event. The largest tangis are attended by hundreds of natives, as well as by some white men. There is food for all. When there isn't,—then it is time to stop the tangi. A tangi without food! Taikiri! Impossible! At the greatest tangis tents and specially built houses are provided for the overflow attendance. At the tangi over King Tawhiao, which was attended by three thousand persons, hundreds of tents and extra whares were erected.

After death, what? This question, in so far as it relates to rewards and penalties for deeds done in the body, would have been answered hazily by the ancient Maori. Of this phase of the world beyond, the Maori knew little. Yet he had so far progressed in religious inquiry as to recognize ten heavens and as many hells. He also believed that some souls returned to the earth as insects; and like many Caucasians to-day, he held that when persons were asleep their souls could leave their bodies and commune with other souls. His belief also embraced recognition of the Greater Existence (Io), the dual principle of nature, and deification of the powers of nature. The spirits of dead ancestors he propitiated. A possible symbol of the Maori's belief in theism I saw in the heitiki, a grotesque, distorted representation of the human form, usually composed of greenstone and hanging pendant from the necks of Maori women.

In olden days the Maoris associated their chief rulers with the gods. In the men of highest rank, the arikis, gods were believed to dwell, and other gods were supposed to attend them. Arikis were the wise men of the tribes, and their powers and duties were manifold. They were the people's guides, they discharged many offices in times of peace, and exercised much authority in times of war. In all cases, however, their authority as priests was limited to things in which the interference of the gods could be discerned.

To-day the Maoris, as a people, know not the religion of their forefathers. In the main the pakeha's religion has become their religion. Thousands of them are church communicants, many of them can quote long passages of Scripture from memory, and the voices of others are heard in daily family worship. A Mormon missionary told me that some native families are such zealous Christians—outwardly, at least—that they have family prayers both morning and night. The majority of Maoris are communicants of the Church of England, but within recent years an astonishing number have embraced the Mormon faith.

Although, generally speaking, the Maori has accepted the fundamental principles of Christianity, his ethical viewpoint often is totally different from that of the European. This was well illustrated in a parliamentary inquiry into alleged "grafting" by a native member of Parliament. The charge, "accepting payment in connection with petitions," apparently astonished the Maoris. In this they could see no more wrong than in the Opposition leader's legitimate acceptance of a present of one thousand pounds from his constituents. In defending his colleague, Dr. Te Rangihiroa said that "the Maori could not be expected to understand pakeha ways, as the pakeha could not himself. The Maori and European ethical systems are totally different."

Singular illustrations of Maori ethics are furnished by native marriage customs. In a trial where one Maori woman was charged with assaulting another wahine, counsel for the complainant said that Maoris believed that "when a husband has been away for seven years he is as good as dead, so that in this case the wife was considered divorced, and in consequence was treated somewhat lightly."

A further illustration is furnished by the murus, or punitive expeditions, that sometimes raid Maori households. With Maoris it has always been a recognized rule that when there has been misconduct on the part of either husband or wife a raid may rightfully be made on the offender's property. By the raided couple a muru may be regarded as the equivalent of a formal divorce. In one plundering excursion I learned that property to the value of five hundred dollars was seized.

The Maoris of old were industrious; idlers they did not have, as they have to-day. Every man able to do so was expected to work, and when the Maoris were not engaged in war they occupied themselves in many ways. On hills they built and fortified their important villages. Around them they dug ditches and sometimes built as many as four palisades, which they adorned with wood carvings that represented years of toil with stone implements.

They built canoes for war and peace; they chiseled and polished weapons of strife; they made ornaments of greenstone, whalebone, and wood, and from the fibres of the flax, the kiekie, and the cabbage tree they wove clothing, mats, and baskets. They were rude surgeons, clever tattooers, hunters, fishers, tillers of the soil. Time they divided into seasons (summer and winter) and moons, and they searched the heavens; for many stars were known to them by name, and comets they dreaded. When the Maoris saw a comet headed toward the earth they recited incantations to prevent a collision.

In the moon the Maoris made a discovery that, if it should ever be substantiated, will forever relegate to the shades of oblivion the blithesome affirmation, "My lover's the man in the moon." For in Marama the Maoris found not a man, but a woman. Her name was Rona. And was Rona a divine and angelic creature? Ah, no. She was only a cook. At Kaipara, says legend, Rona was cooking, and was on her way to get a calabash of water, when she stumbled and fell. In her rage Rona cursed the innocent moon. The moon, becoming nettled, descended, and seized the angry wahine. The woman stoutly held to a tree, but the moon prevailed, and carried Rona, tree, and calabash to the sky.

One of the commonest of old Maori occupations was tattooing. Among both men and women it was the fashion to be tattooed. The men tattooed because they believed it improved their faces and made them look more resolute; and, further, because Maori women did

MAORI WAHINE WITH MAT OF KIWI FEATHERS AND

PENDENT HEITIKI

not regard the attentions of untattooed men with the highest favor. The women tattooed (usually only on lips and chin, as to-day) because the Maori tangata, unlike the Caucasian man, did not like red-lipped sweethearts or wives.

But that was in the long ago. Tattooing, excepting among women,—and many of them are no longer tattooed,—is out of fashion. Not for forty years have Maori men been tattooed.

The busy Maori of the past did not spend all his peaceful days working. He amused himself in a variety of ways. He danced, he sang, and on drums, whistles, and nose flutes he played. His ear for music was keen; in rhythm he was skilled; and his voice was deep and well matured. He engaged in many sports and games, and in the wharetapere, the house of amusement, he sometimes entertained himself all night. There was wrestling on land and in water; there were tobogganing, rope-skipping, stilt-walking, and kite-flying. Tops were spun, hoops were rolled, and for the children there were games of see-saw and hide-and-seek.

And the Maori also feasted. At the hakari, greatest of his ancient festivals, he piled food on high pyramidal stages. There sweet potatoes, taro, eels, fish, gourds, and many foods of tree, creeper, and fern were heaped in profusion. There, welcomed by songs and by speeches of pacing orators, visiting tribes assembled to partake of prodigal hospitality.

The Maori also spent many hours in making himself as attractive as possible. His vanity was appeased with ornaments, paint, and bright colors. To the hair much attention was paid by persons of rank, including chiefs, whose hair usually was long in peaceful days. For beards the majority of men did not care, because they hid the tattooing, and so facial hairs were extracted with mussel-shell pincers.

Those were the days of knobbed heads. Hair knobs were "the rage." On the back of some heads there were from three to six or more. They were fastened with combs, and their possessors were very careful to keep them in place. The coiffures were brightened with the feathers of birds, and one feathery decoration was a war plume of twelve huia feathers, single ones of which are worth now, I was told, as much as five dollars. But time has wrought her changes in this land as elsewhere. Befeathered Maoris are still common in New Zealand, but their feathers are worn in European hats. The war plume is no longer seen, the strife-provoking suspicions of early days exist no more. Rongo, god of sweet potatoes, has more followers than the warring Tu.

The modernized Maori is not much like his mat-clothed, tattooed ancestors. The flax mat and kilt have been superseded by European apparel, in many cases by carefully pressed suits and other demands of modern fashion. Even such conveniences as telephones and automobiles are possessed by Maoris.

The Maori is absorbing the education and customs of his vanquishers, but in turn he himself is being absorbed. Hear the lament of Chief Te Huki, uttered in 1911:—

"You Maoris are being superseded, absorbed by the pakehas. We have Maori features, true, but our skins are pakeha. The tide has turned, and is slowly but surely flowing out into oblivion. When the tide turns again, it will be salt, it will be pakeha. While the river Ruamahanga flowed and rippled across the land it was sweet, pure, and fresh; but when it reached the sea of Kiwa, it was lost, lost, lost!"