Popular Science Monthly/Volume 37/September 1890/Some Natives of Australasia

| SOME NATIVES OF AUSTRALASIA.[1] |

By ELISÉE RECLUS.

SHAKEN collectively, the Dayak populations differ from the civilized Malays by their slim figure, lighter complexion, more prominent nose, and higher forehead. In many communities the men carefully eradicate the hair of the face, while both sexes file, dye, and sometimes even pierce the teeth, in which are fixed gold buttons. The lobe of the ear is similarly pierced for the insertion of bits of stick, rings, crescent-shaped metal plates, and other ornaments, by the weight of which the lobe is gradually distended down to the shoulder. In several tribes the skulls of the infants are artificially deformed by means of bamboo frames and bandages.

The simple Dayak costume of blue cotton with a three-colored stripe for border is always gracefully draped, and the black hair is usually wrapped in a red cloth trimmed with gold. Most of the Dayaks tattoo the arms, hands, feet, and thighs, occasionally also the breast and temples. The designs, generally of a beautiful blue color on the coppery ground of the body, display great taste, and are nearly always disposed in odd numbers, which, as among so many other peoples, are supposed to be lucky. Amulets of stone, filigree, and the like, are also added to the ornaments to avert misfortune. In some tribes coils of brass wire are wound round the body, as among some African peoples on the shores of Victoria Nyanza.

Many Dayak tribes are still addicted to head-hunting, a practice which has made their name notorious, and which but lately threatened the destruction of the whole race. It is essentially a religious practice—so much so that no important act in their lives seems sanctioned unless accompanied by the offering of one or more heads. The child is born under adverse influences unless the father has presented a head or two to the mother before its birth. The young man can not become a man and arm himself with the mandau, or war-club, until he has beheaded at least one victim. The wooer is rejected by the maiden of his choice unless he can produce one head to adorn their new home. The chief fails to secure recognition until he can exhibit to his subjects a head secured by his own hand. No dying person can enter the kingdom beyond the grave with honor unless he is accompanied by one or more headless companions. Every rajah owes to his rank the tribute of a numerous escort after death.

Among some tribes, notably the Bahu Trings, in the northern part of the Mahakkam basin, and the Ot-Damons of the upper Kahajan, the religious custom is still more exacting. It is not sufficient to kill the victim, but before being dispatched he must also be tortured, the corpse sprinkled with his blood, and his flesh eaten under the eyes of the priest and priestesses, who perform the prescribed rites. All this explains the terror inspired by the Dayaks in their neighbors, and the current belief that they are sprung from swords and daggers that have taken human form. With the gradual spread of Islam the Dayaks of the British and Dutch possessions are slowly abandoning their bloodthirsty usages. At the same time the head-hunters themselves, strange to say, are otherwise the most moral people in the whole of Indonesia. Nearly all are perfectly frank and honest. They

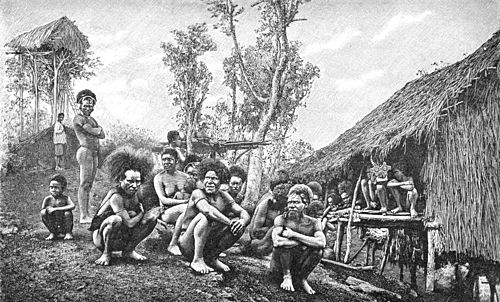

Fig. 1.—Dayak Types, Borneo.

scrupulously respect the fruits of their neighbors' labor, and in the tribe itself murder is unknown.

The population of New Guinea, variously estimated at from half a million to two millions, comprises a very large number of groups differing greatly from each other in stature, complexion, shape of the skull, and other physical features, as well as in their usages and mental qualities. Several tribes approach the Indonesian type, as found in Borneo and Celebes, while others resemble the Malays, and are described by travelers as belonging to this race. But, although there is no ethnical uniformity, as seemed probable from the reports of the early explorers, the Papuan element, whence the great island takes the name of Papuasia, certainly predominates over all others.

On the whole the Papuans are somewhat shorter than the Polynesians, the average height being about sixty-two to sixty-four inches. They are well proportioned, lithe, and active, and display surprising skill both in climbing trees and in using the feet for prehensile purposes. Most Papuans have a very dark skin, but never of that shiny black peculiar to the Shilluks of the White Nile, the Wolofs of Senegal, and some other African peoples. The eyebrows are well marked, the eyes large and animated, the mouth large but not pouting, the jaw massive. Among the northwestern Papuans, regarded by Wallace as representing the type in its purity, the nose is long, arched, and tipped downward at the extremity, and this is a trait which the native artists never fail to reproduce in the human effigies with which they decorate their houses and boats. Another distinctive characteristic of numerous tribes is their so-called mop-heads, formed by superb masses of frizzly hair, no less abundant than that of the Brazilian Cafusos, and, as in their case, possibly indicating racial interminglings.

However backward they may be in other respects, most of the Papuans are endowed with a highly developed artistic feeling, and as carvers and sculptors they are far superior to most of the Malayan peoples. Having at their disposition nothing but bamboos, bone, banana-leaves, bark, and wood, they usually design and carve with the grain—that is, in straight lines. Nevertheless, with these primitive materials they succeed in producing extremely elegant and highly original decorative work, and even sculpture colossal statues representing celebrated chiefs and ancestors. Thanks to this talent, they are able to reproduce vast historic scenes, and thus record contemporary events. Numerous tribes have their annals either designed on foliage or depicted on rocks in symbolic writing. The skulls of the enemies slain in battle, which are carefully preserved to decorate the houses, are themselves often embellished with designs traced on masks made of wax and resin. On the banks of the Fly River these skulls are also used as musical instruments.

The island of Tasmania has already been completely "cleared" by the systematic destruction of its primitive inhabitants, who were estimated at about seven thousand on the arrival of the

Fig. 2.—Group of Koyari Chiefs, Southeast New Guinea.

whites, and who were said to be of a remarkably gentle and kindly disposition. On December 28, 1834, the last survivors, hounded down like wild beasts, were captured at the extremity of a headland, and this event was celebrated as a signal triumph. The successful hunter, Robinson, received a government reward of six hundred acres and a considerable sum of money, besides a public subscription of about eight thousand pounds.

The captives were at first conveyed from islet to islet, and then confined to the number of two hundred in a marshy valley of Flinders Island, washed by the stormy waters of Bass Strait. They were supplied with provisions and some lessons in the catechism; their community was even quoted as an example of the

Fig. 3.—Lalla Rookh, the Last Tasmanian.

progress of Christian civilization. But after ten years of residence in this place of exile more than three fourths of the natives had perished. Then pity was taken on them, and the twelve surviving men, twenty-two women, and ten children, nearly all half-breeds, were removed to a narrow promontory at Oyster Cove, near Hobart, and placed under some keepers, who enriched themselves at their expense. In 1800 the Tasmanian race was reduced to sixteen souls; in 1869 the last man perished, and in 1876 "Queen" Truganina, popularly known as Lalla Rookh, followed her people to the grave. But there still survived a few half-castes, and in 1884 a so-called "Tasmanian" woman obtained a grant of land from the Colonial Parliament.

The Fijians present affinities both with the western Melanesians and eastern Polynesians, and are at least partly of mixed descent, although the majority approach nearest to the former group. They are tall and robust, very brown and coppery, sometimes even almost black, with abundant tresses intermediate between hair and wool. Half-breeds are numerous and are often distinguished by almost European features. Till recently they went nearly naked, wearing only the loin-cloth or skirt of vegetable fiber, smearing the body with oil, and dyeing the hair with red ochre. The women passed bits of stick or bark through the pierced lobe of the ear, and nearly all the men carried a formidable club; now they wear shirts, blouses, or dressing-gowns, or else drape themselves in blankets, and thus look more and more like needy laborers dressed in the cast-off clothes of their employers. They display great natural intelligence, and, according to Williams, are remarkable for a logical turn of mind, which enables Europeans to discuss questions with them in a rational way. Their generosity is attested by the language itself, which abounds in terms meaning to give, but has no word to express the acts of borroAving or lending. Compared with their Polynesian neighbors, they are also distinguished by much reserve. Their meke, or dances, always graceful and marked by great decorum, represent little land or sea dramas, sowing, harvesting, fishing, even the struggles between the rising tides and rocks.

Cannibalism entered largely into the religious system of the Fijians. The names of certain deities, such as the "god of slaughter," and the "god eater of human brains," sufficiently attest the horrible nature of the rites held in their honor. Religion also taught that all natural kindness was impious, that the gods loved blood, and that not to shed it before them would be culpable; hence those wicked people who had never killed anybody in their lifetime were thrown to the sharks after death. Children destined to be sacrificed for the public feasts were delivered into the hands of those of their own age, who thus served their apprenticeship as executioners and cooks. The banquets of "long pig"—that is, human flesh—were regarded as a sacred ceremony from which the women and children were excluded; and while the men used their fingers with all other food, they had to employ forks of hard wood at these feasts. The ovens also in which the bodies were baked could not be used for any other purpose. Notwithstanding certain restrictions, human flesh, was largely consumed, and in various places hundreds of memorial stones were shown which recalled the number of sacrifices.

Fig. 4.—Tattooed Native of the Marquesas Islands.

From the ethnical standpoint Polynesia forms a distinct domain in the oceanic world, although its inhabitants do not appear to be altogether free from mixture with foreign elements. The vestiges of older civilizations differing from the present even prove that human migrations and revolutions have taken place in this region on a scale large enough to cause the displacement of whole races. The curious monuments of Easter Island, although far inferior in artistic work to the wood-carvings of Birara and New Zealand, may perhaps be the witnesses of a former culture, no traditions of which have survived among the present aborigines. These monuments may possibly be the work of a Papuan people, for skulls found in the graves differ in no essential feature from those of New Guinea.

The Polynesians, properly so called, to whom the collective terms Mahori and Savaiori have also been applied, and who call themselves Kanaka, that is, "men" have a light-brown or coppery complexion, and rather exceed the tallest Europeans in stature. In Tonga and Samoa nearly all the men are athletes of fine proportions, with black and slightly wavy hair, fairly regular features, and proud glance. They are a laughter-loving, light-hearted people, fond of music, song, and the dance, and where not visited by wars and the contagion of European "culture" the happiest and most harmless of mortals. When Dumont d'Urville questioned the Tukopians as to the doctrine of a future life, with rewards for the good and punishment for the wicked, they replied, "Among us there are no wicked people."

Tattooing was wide-spread, and so highly developed, that the artistic designs covering the body served also to clothe it; but this costume is now being replaced by the cotton garments introduced by the missionaries. In certain islands the operation lasted so long that it had to be begun before the children were six years old, and the pattern was largely left to the v skill and cunning of the professional tattooers. Still, traditional motives recurred in the ornamental devices of the several tribes, who could usually be recognized by their special tracings, curved or parallel lines, diamond forms, and the like. The artists were grouped in schools, like the Old Masters in Europe, and they worked not by incision as in most Melanesian islands, but by punctures with a small, comb-like instrument slightly tapped with a mallet. The pigment used in the painful and even dangerous operation was usually the fine charcoal yielded by the nut of Aleurites triloba, an oleaginous plant used for illuminating purposes throughout eastern Polynesia.

In Samoa the women were much respected, and every village had its patroness, usually the chief's daughter, who represented the community at the civil and religious feasts, introduced strangers to the tribe, and diffused general happiness by her cheerful demeanor and radiant beauty. But elsewhere the women, though as a rule well treated, were regarded as greatly inferior to the men. At the religious ceremonies the former were

Fig. 5.—Samoan Women.

noa, or profane; the latter ra, or sacred; and most of the interdictions of things tabooed fell on the weaker sex. The women never shared the family meal, and they were regarded as common property in the households of the chiefs, where polygamy was the rule. Before the arrival of the Europeans, infanticide was systematically practiced; in Tahiti and some other groups there existed a special caste, among whom this custom was even regarded as a duty. Hence, doubtless, arose the habit of adopting strange children, almost universal in Tahiti, where it gave rise to all manner of complications connected with the tenure and inheritance of property.

In Polynesia the government was almost everywhere centered in the hands of powerful chiefs, against whose mandates there was no appeal. A vigorous hierarchy separated the social classes one from another, proprietors being subject to the chiefs, the poor to the rich, the women to the men; but over all custom reigned supreme. This law of taboo, which regulated all movements and every individual act, often pressed hard even on its promulgators, and the terrible penalties it enforced against the contumacious certainly contributed to increase the ferocity of the oceanic populations. Almost the only punishment was death, and human sacrifices in honor of the gods were the crowning religious rite. In some places the victims were baked on the altars, and their flesh, wrapped in taro-leaves, was distributed among the warriors.

Yet, despite the little value attached to human life, the death of adult men gave rise to much mourning and solemn obsequies. Nor was this respect for the departed an empty ceremonial, for the ancestors of the Polynesians were raised to the rank of gods, taking their place with those who hurled the thunderbolt and stirred up the angry waters. A certain victorious hero thus became the god of war, and had to be propitiated with supplications. But the common folk and captives were held to be "soulless," although a spirit was attributed to nearly all natural objects.

- ↑ From Oceanica, the fourteenth volume of Reclus's great illustrated work on The Earth and its Inhabitants, now in course of publication by D. Appleton & Co.