Popular Science Monthly/Volume 41/May 1892/Cave Dwellings of Men

| CAVE DWELLINGS OF MEN. |

By W. H. LARRABEE.

STORIES of men who lived or worked in caves abound in history, mythology, and folk-lore tales. The youthful imagination is charmed with accounts of robbers' caves, from that of the forty thieves down to those described in Gil Blas and those which are associated with the robber period of the history of the Mississippi Valley. Mythology furnishes caves of giants, those to which heroes have resorted, and the homes of supernatural beings or of gnomes like the Niebelungen and the "little people." Such stories are suggested by the obvious fact that a cave may afford a safe and convenient place of refuge when no better is at hand; and their imaginative features are the outcome of the rarity or remoteness of experiences of cave-life within historic times—distance lending enchantment to the view.

Tribes of cave-dwelling men, or troglodytes, are described by ancient writers as having lived in Egypt, Ethiopia, on the borders of the Red Sea, and in the Caucasus. The Red Sea region was called by the Greeks from this fact Troglodytice. Some of the ancient caves in Arabia are still occupied by Bedouins.

The caves of the troglodytes near Ain Tarsil, in Morocco, which have been visited by Balanza and Sir Joseph Hooker, and described by a correspondent of the London Times, are situated in a narrow gorge, the cliffs of which rise almost perpendicularly from a deep valley, and are cut in the solid rock at a considerable height from the ground. In some places they are in single tiers, and in other places two or three tiers, one above the other, and inaccessible except by ropes and ladders. The entrances give access to rooms of comfortable size, furnished with windows, which were in some cases connected with other smaller rooms, also furnished with windows. The appearance of the caves, attesting that great pains were taken to secure comfort, is hardly consistent with the conception of the troglodytes as savages, which has been drawn from Hanno's account of them. Caves have been much used for burials, and have suggested the form of various artificial burial-places. The ancient Egyptians used natural caves or hollowed out artificial ones, preparing elaborate suites of chambers, ante-chambers, and recesses, and adorning them with brilliant paintings and art-works of religious significance. The recovery and exploration of these tombs constitute one of the most interesting and profitable branches of modern archaeological research. The most ancient real-estate transaction recorded in a historical book is the purchase of the cave of Machpelah from the children of Heth by Abraham, to be his family burial-place; and it is still guarded as such at Hebron by a Mohammedan mosque, which only the children of the faith and no infidel can pass.

Remarkable vestiges of the cave-life of antiquity may be seen in the rock-hewn city of Petra in Edom, some fifty miles south of the Dead Sea. The valley in which it stood is lined on either side with the remains of tombs, temples, and perhaps habitations, excavated out of the rock. These structures are supposed to date from a remote antiquity. In later times they were faced with architectural fronts of a more or less imposing character. They are believed to have been used chiefly as places of burial. But there is reason to suppose that most of them were originally intended and used as habitations. Many of the chambers have no resemblance to tombs, but are such as a primitive race would construct to live in. Most of these have closets and recesses suitable for family uses, and many have windows in front, which would be superfluous in tombs. It may be that in the course of time, as customs and people changed, these chambers were abandoned for other houses, to be subsequently used as places of sepulture.

Evidences are found in caves the world over of their use by prehistoric men from the stone ages down—so frequently as to indicate that they were at one or more periods the usual dwellings of the race, and archæologists have based upon them the type or types of cave-men. The evidences of human abode are often found mingled with traces of animals, some of extinct species, which seem to have shared man's occupancy or contested with him for it, or to have possessed the caves alternately with, him. They have furnished fruitful fields for archæological and geological research, and the excavation of them has afforded valuable information concerning the condition and surroundings of the most primitive men, and incidentally as to the age in which they lived. The most noted localities where the earlier finds of ancient stone implements were made in France were habitations of cave-dwellers or in the immediate vicinity of such, habitations, and the science of palæolithic arcæhology was thus based in its beginning upon the relics left by men of this type. In Kent's Cavern, Torquay, which was one of the first of these palæolithic abodes to be studied in England, human bones or articles of human manufacture have been found in two or three different strata, the oldest ones under conditions betokening extreme antiquity and in company with the remains of animals that were extinct long before the historical period. The first discoveries were among the earliest evidences that were obtained of man's having had a greater antiquity than had till then been ascribed to him, and were received incredulously by a public which the thought struck as contradictory to revelation. The cave was examined year after year by scientific committees. The findings were confirmed, and shown to be in place and so situated as to forbid the supposition of the human remains being of more recent origin than the accompanying deposits. Similar remains have been found in many caves in all countries, and now constitute

Fig. 1.—Corinthian Tomb at Petra.

only one among several kinds of evidences of man's glacial and preglacial existence. A cave at Cravan, near Belfort, France, appears to have been extensively used as a prehistoric burial-place of the polished-stone period. It contained a number of skeletons in such positions as suggested deliberate arrangement, and with them were beautifully ornamented vases, polished-stone bracelets, and a mat of plaited rushes. The cave of Marsoulas, in the Haute-Garonne, France, was inhabited by man several times during the palæolithic age. The relics of what is designated as the second occupation are interesting on account of the specimens of artistic taste they afford. Besides the usual instruments of silex, arrow-points, and the like, were found some peroxide of manganese, which was probably used in tattooing, and engraved designs; a piece of bone adorned with a regular ornamentation, engravings very much like those found in the valley of La Vézère; and a piece of rib having an ovibos (or musk ox) carved upon it, in which, according to the Marquis de Nadaillac, the design is treated with exact knowledge of anatomical forms, the relief is brought out by shadings, and the drawing is vigorous. One of the recent excursions of the French Association for the Advancement of Science took in its way the grottoes of Lamouroux and Montrajoux, near Brive. The grottoes of Montrajoux are natural and have been used as the abodes of shepherds' families since the age of the reindeer. Those of Lamouroux are the work of man, as is attested by the marks of the pick which they still bear. They are grouped in Line and arranged in different stories which communicate with one another, there being in some places five stories. Some were distinguished by benches in the back, bearing tying-holes on their edges, which suggested that they had been occupied by the domestic animals. The situation of these grottoes in the neighborhood of the Château of Turenne, crowning the heights, induces the supposition that they served as places of refuge for Protestants during the religious wars. The bone caves of Borneo appear to have been occupied by men who were acquainted with the use of manufactured iron. The remains have recently been discovered on the banks of the Amu Daria or Oxus River, in central Asia, of a considerable city which was composed of caverns hewn in the rock. It seems, from the inscriptions, coins, and other objects found in it, to have been in existence in the second century of the Christian era. Some of the houses were of several stories.

Dr. Arthur Mitchell, of Edinburgh, in a lecture delivered a few years ago on the condition and antiquity of the cave-men of western Europe, showed of the men of the caves which he had

Fig. 2—Upper figure—a piece of bone, bearing regular designs. Lower figure—a piece of rib with an ovibos engraved upon it. Both found in the grotto of Marsoulas (Haute-Garonne).

particularly in mind—that their weapons of war and the chase were made of bone or horn, and highly finished, while their implements of stone were extremely rude and calculated chiefly to serve as tools in the making of their bone implements, so that they were placed in the bone rather than the stone age of civilization. From an elaborate examination of the objects which the cave-man has left, displaying an art faculty, and from the study of the crania of the cave people themselves, he argued that they must have possessed a high capacity for culture in all directions, and must have been as complete in their whole manhood as living Europeans. He was disposed to put their age only a few thousand years back.

The cave temples of India are famous and most curious specimens of architecture. They date from near the beginning of the Christian era. The best-known ones, those of Elephanta, have been described and pictured over and over again. The great cave, according to Mr. James Burgess, in The Rock-cut Temples

Fig. 3.—Façade of the Temple of Pandu Lena, near Nassik, India. (From a drawing by M. Albert Tissandier.)

of Elephanta or Ghârâpuri, occupies a space having an extreme length of two hundred and sixty feet, with a depth into the rock of a hundred and fifty feet. It has three entrances—one in the side and one at each end—which are each about fifty-four feet wide, and divided into three doors by pillars fully three feet in diameter and sixteen feet high. This subdivision is repeated over the entire area of the underground temple, which may be described as consisting of eight parallel rows of such columns about fifteen feet apart. One of the quadrangular clumps of pillars is built round and incloses the shrine. Opposite the north entrance is the Trimusti, or Trinity, one of the most remarkable sculptured religious relics in the world. It consists of three united half-length figures, each head being elaborately carved and ornamented, and is seventeen feet high and twenty-two feet wide. Besides the great caves there are three others on the island. They consist of a central excavation for the shrine, usually about twenty feet square, with attached cells or apartments for priests, two, four, and six respectively in number, each about sixteen feet square. The temples

Fig. 4.—The Temples of Kylas Ellora, India. (From a drawing by M. Albert Tissandier.)

of Pandu Lena, constructed, according to the inscriptions they bear, about 129 b. c., are remarkable for the profusion and perefection of their ornamentation, which, like that of the cave temples generally, seems to be designed to imitate constructions of wood. Those of A junta consist of four temples and twenty-three monasteries, built in the face of an almost perpendicular cliff. They were begun about 100 b. c., and have remained in the condition in which they are now seen since the tenth century. They are excavated en suite in the amygdaloid of the mountain, and are described as being of grand aspect, upheld by superb columns with

Fig. 5.—Plan of the Temples of Kylas.

curiously sculptured capitals and adorned with admirable frescoes reproducing the ancient Hindu life. The temples of Ellora are of different construction. Built in a sloping hill, it was necessary, in order to obtain a suitable height for the facade, to make a considerable preliminary excavation. In the group of these temples known as the Kylas, according to M. Albert Tissandier, the excavation has been carried around three sides, so as to isolate in the center an immense block, in which a temple with annexed chapels has been cut. The buildings are thus all in the open air, carved in the form of pagodas. Literally covered with sculptures composed with consummate art, they form a unique aggregate. They appear to be placed upon a fantastic sub-base on which all the gods of the Hindu mythology, with symbolical monsters and rows of elephants, are sculptured in alto rilievo, forming caryatides of strange and mysterious figure, well calculated to strike the imagination of the ancient Hindu population. The interior of the central pagoda is adorned with sixteen magnificent columns, which, as well as the side walls, were once covered with paintings; and, with the central sanctuary of the idol, is composed with a correct understanding of architectural proportions. The two exit doors open upon a platform on which are five pagodas of lesser importance but of architectural merit and artistic ornamentation corresponding to those of the main building. Around these isolated temples excavations have been made into the sides of the mountain, in which are found a cloister adorned with bas-reliefs representing the principal gods of the Hindu pantheon; other halls, likewise sculptured; and various other  Fig. 6.—Yaki Deshik Caves of Afghanistan. features implying great labor and refined artistic taste and skill.

Fig. 6.—Yaki Deshik Caves of Afghanistan. features implying great labor and refined artistic taste and skill.

At Bamian, in Afghanistan, are five colossal statues (probably Buddhas) seated in niches which have been dug out in the cliff, while the rock is pierced with caves which are supposed to have been excavated by Buddhist monks during the first five centuries of the Christian era. Many of the caves are inhabited. Some of them are shown to have been bricked up in front, and both niches and caves are adorned with paintings and ornamental devices. Captain F. de Laessoe has described a number of caves which were excavated for habitation in the sandstones of the right bank of the Murghab River, near Penjdeh, in Afghanistan. One of them (Fig. 6) consists of a central passage a hundred and fifty feet long and nine feet broad and high, having on each side staircases and doors leading to rooms of different sizes. Each room has attached to it a small chamber, with a well in which possibly water brought up from the river was stored; and is also provided with small niches in the walls on which the lamps were placed and where marks of soot can still be seen. The entrances from the main passage to the rooms were shut with folding doors on wooden hinges, of which the socket-holes of the hinges and holes for the admission of the arm behind the door to draw back the bolt are the only traces now to be seen. This structure had an upper story, but much less extensive than the lower story. Many other caves, similarly constructed but containing fewer rooms, are found all along the valley. At one of them the cliff is so well preserved as to show how access was gained. It was by means of holes cut in the rock for steps, which could be easily climbed by the aid of a rope hanging down from above.

Vestiges of cave dwellings are very abundant in America, but they have not been made the subject of special study to so great an extent as those of Europe. They are prehistoric, ancient, or relatively modern, and represent various stages of civilization in those who inhabited them. Some are found as far north as Alaska, where, according to Dr. Peet, who has published in the American Antiquarian excellent illustrated summaries of the results of the explorations of the cliff and cave dwellings, "they are associated with shell-heaps; others in the Mississippi Valley, where they are closely connected with the mounds; others in the midst of the cañons of Colorado and Arizona, where they are associated with structures like the Pueblos; others in the central regions on the coasts of Lake Managua, in Nicaragua; and still others in the valley of the Amazon in South America." According to Mr. William H. Dall, the cave-dwellers of Alaska were neolithic. The caves in Tennessee are described by Prof. F. W. Putnam as containing tokens of a neolithic character; but it is uncertain whether they preceded the mounds or were contemporaneous with them. Dr. Earl Flint has described caves in Nicaragua which strike him as being very ancient; and certain caves in Brazil are supposed to be palæolithic.

The most interesting of the American cave dwellings, and those which have received the most attention, are those which are associated and almost confounded with the cliff dwellings of the cañons of Arizona and Colorado. So nearly related are the cliff and cave dwellings of this region, in fact, that it seems to have been to a considerable extent a question of the shaping of the rock whether the habitation should be one or the other. Regarding the two as a whole, they were very numerous, and indicate the former existence of a large population. Major Powell is quoted as having expressed surprise at seeing in the region nothing for whole days but cliffs everywhere riddled with human habitations, which resembled the cells of a honeycomb more than anything else. Yet it is probable that only a small fraction of these singular dwellings have been seen, while the number of those that have been even only superficially explored is much less.

An excellent, finely illustrated description of some of these

Fig. 7.—Cave Dwellings in the Rio San Juan.

ancient dwellings in the Rio Verde Valley was given, from his own personal observations, by Dr. Edgar A. Mearns, in The Popular Science Monthly for October, 1890. But his attention was devoted chiefly to the buildings in exposed situations of the Pueblo style of architecture; while he speaks of having seen lines of black holes emerging upon the narrow ledges, which he was told were cave dwellings of an extinct race. He mentions also walled buildings of two kinds those occupying natural hollows or cavities in the face of the cliffs, and those built in exposed situations; the former, whose walls were protected by sheltering cliffs, being sometimes found in almost as perfect a state of preservation as when deserted by the builders, unless the torch has been applied. "Another and very common form of dwellings," Dr. Mearns continues, "is the caves which are excavated in the cliffs by means of stone picks or other instruments. They are found in all suitable localities that are contiguous to water and good agricultural land, but are most numerous in the vicinity of large casas grandes."

The cave dwellings are more prominent in other accounts of the region, and seem to be a very important feature in some of the canons. The majority of those known are in the valleys of the Colorado and the Rio Doloroso, Rio San Juan, and Rio Mancos, its tributaries. A village, if we might call it that, on the San Juan, described by Mr. W. H. Holmes, is surmounted by three estufas or towers, one rectangular and two circular, each over a different group of cave dwellings. A short distance from this ruin are the remains of another tower, built on a grander scale. These structures are supposed by Mr. Holmes to have been the fortresses, council chambers, and places of worship of the cliff and cave dwellers.

The great Echo Cave on the San Juan is described by Mr. W. H. Jackson as situated on a bluff about two hundred feet high, and as being one hundred feet deep. "The houses occupy the eastern half of the cave. The first building was a small structure, sixteen feet long and from three to four feet wide. Next came an open space, eleven feet long and nine feet deep, probably a workshop. Four holes were driven into the smooth rock floor, six feet apart, probably designed to hold the posts for a loom. . . . There were also grooves worn into the rock where the people had polished their stone implements. The main building comes next, forty-eight feet long, twelve feet high, and ten feet wide, divided into three rooms, with lower and upper story, each story being five feet high. There were holes for the beams in the walls, and window-like apertures between the rooms, affording communication to each room of the second story. There was one window, twelve inches square, looking out toward the open country."[1] There were also holes in the upper rooms, which may have been used for peep-holes. Beyond these rooms the wall continued one hundred and thirty feet farther, and the space was divided into rooms of unequal length. The appearance of the place impressed Mr. Jackson as indicating that the family were in good circumstances. These are single specimens of a class of dwellings of which there are probably many hundreds. The ages of these dwellings and the conditions under which they were built and

Fig. 8.—Echo Cave on the Rio San Juan.

occupied are unknown. The climate favors the preservation of objects, so that they may be of considerable antiquity; and there is no reason for supposing they were not inhabited down to a comparatively recent period. The objects found within the cliff and cave dwellings, some of which are represented in Dr. Mearns's article, indicate a considerable degree of civilization.

An account was published by Mr. Theodore Hayes Lewis, in Appletons' Annual Cyclopædia for 1889, of some curious drawings that are found in caves at St. Paul, Winona, and Houston Counties, Minn., La Crosse County, Wis., and Allamakee County, Iowa. They include representations of the human form, fish, snakes, animals, and conventional figures.

Many accounts of travelers go to show that residence in caves is not rare in modern times, and that it constitutes a feature of life, though not an important one, in some of the most civilized countries in Europe. Some of the most interesting pages in Mrs. Olivia M. Stone's account of her visit to the Canary Islands (Teneriffe and its Six Satellites) relate to the cave villages, still inhabited by a curious troglodyte population—mostly potters—found in various places in Gran Canaria. Appositely to an account by the Rev. H. F. Tozer of certain underground rock-hewn churches in southern Italy, Mr. J. Hoskyns Abrahall relates that when visiting Monte Vulture, and while a guest of Signor Bozza, at Barili, having expressed surprise at learning the number of inhabitants in the place, his host told him that the poor lived in caves hollowed out of the side of the mountain, and took him into one of the rock-hewn dwellings; and he accounts for their existence by the facility with which they are formed.

Fig. 9.—Gh'mrassen, in the Ourghemma, Southern Tunis, with the Rock-cut Dwellings.

The rock-cut village of Gh'mrassen, in the Ourghemma, southern Tunis, consists of rows of snug family dwellings, close to each other, hollowed out of the side of a cliff, the top of which at an overhanging point, is crowned by the remains of a small mosque.

At a recent meeting of the Royal Geographical Society of Madrid, Dr. Bide gave an account of his exploration of a wild district in the province of Caceres, which he represented as still inhabited by a strange people, who speak a curious patois, and live in caves and inaccessible retreats. They have a hairy skin, and have hitherto displayed a strong repugnance to mixing with their Spanish and Portuguese neighbors. Roads have lately been pushed into the district inhabited by these "Jurdes," and they are beginning to learn the Castilian language and attend the fairs and markets.

Some disused rock-hewn dwellings are mentioned in Meyer's Guide-Book as existing near the ancient Klusberg in the Hartz

Fig. 10.—Cave Dwellings near Langenstein, in the Hartz Mountains. (From a drawing by E. Krell.)

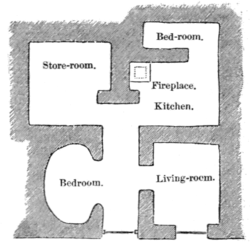

Mountains. Herr E. Krell describes in a German periodical a group of such dwellings, now inhabited, near the village of Langenstein in the same region. There are some twenty of them, each furnished with a door and a window, and inhabited altogether by about forty persons. The oldest of them was made  Fig. 11.—Plan of a Cave Dwelling near Langenstein. about thirty years ago, by a poor, newly married couple who found the conditions of life in the village too hard. It was gradually enlarged, by patient excavation in the rock, until it has been made a comfortable and convenient dwelling. The house has a neatly kept entrance, with a hallway, a living-room on the right, in which is the only window, a bedroom on the left of the hall; in the rear a spacious store-room on the left, and a kitchen with a fireplace on the right; and behind the kitchen another bedroom. The chimney is carried up through the roof, and where it comes out above the surface of the ground is well guarded with a wall of stones. Although the back rooms are not directly lighted from without, they receive sufficient light from the front; the houses, as a whole, are dry, warm in winter and cool in summer, and do not suffer from lack of ventilation; and their inhabitants, as a rule, are a healthy and vigorous people. Some of the proprietors have whitened the fronts of their dwellings, and have planted gardens in the ground over them and in front of them, so as to give their homes a not unpleasing air; and the cave dwellings are much drier and more healthful than city basements.

Fig. 11.—Plan of a Cave Dwelling near Langenstein. about thirty years ago, by a poor, newly married couple who found the conditions of life in the village too hard. It was gradually enlarged, by patient excavation in the rock, until it has been made a comfortable and convenient dwelling. The house has a neatly kept entrance, with a hallway, a living-room on the right, in which is the only window, a bedroom on the left of the hall; in the rear a spacious store-room on the left, and a kitchen with a fireplace on the right; and behind the kitchen another bedroom. The chimney is carried up through the roof, and where it comes out above the surface of the ground is well guarded with a wall of stones. Although the back rooms are not directly lighted from without, they receive sufficient light from the front; the houses, as a whole, are dry, warm in winter and cool in summer, and do not suffer from lack of ventilation; and their inhabitants, as a rule, are a healthy and vigorous people. Some of the proprietors have whitened the fronts of their dwellings, and have planted gardens in the ground over them and in front of them, so as to give their homes a not unpleasing air; and the cave dwellings are much drier and more healthful than city basements.

Another group of inhabited caves is described in La Nature by M. Brossard de Corbigny as stretching for the length of a kilo

Fig. 12.—The Grottoes of Meschers, in the Bluff, Charente-Inférieure, France.

(From a water-color sketch by M. Brossard de Corbigny.)

metre along the right bank of the river Gironde, at Meschers, in the Charente-Inférieure, France. "They are excavated in a high bluff of shell-rock, which is crowned above them by a number of windmills, some still active while others are disused, and face the broad river, commanding a view of the sea and the Cordouan Tower in the distance. The caves are partly natural and partly the work of man. They can not be seen from the top of the bluff, and are accessible by goat-paths descending from the mills—not very pleasant walking for women and children, especially where it has been necessary to cut stepping-notches in the rock. Not all the paths are equally difficult of descent, and some leading to the stations of the lobster-fishers go down to a kind of ladder that reaches to the water's edge. Whatever path one follows, he is sure at about a third of the distance down to come upon an excavation suggesting the nest of some gigantic sea-bird of the olden time; but he will soon observe that the bottoms of the caves and the roofs have been made smooth by the hand of man, while the great openings looking out upon-the sea bear marks of erosion by the southwest winds and the rains. Most of these grottoes were inhabited fifty years ago, but the majority of them have been abandoned in consequence of the land-slides and the development of the knowledge and desire of a better way of living. Three of them are still occupied by persons who boast that they are very comfortable in them—warm in winter with their southern exposure and complete protection from the north, and enjoying a refreshing coolness in the summer. The caves are free from moisture, and cost no rent except a slight fee paid to the proprietor of the ground above them. The natural opening on the side of the sea is closed not very tightly with boards or stones, in which one or two windows admit a sufficient light. The house is usually composed of two rooms, separated by a partition which was left in the hollowing out of the cave, and the furnishings are as comfortable as those possessed by the majority of the peasants of the

Fig. 13.—Entrance to the Grotto La Femme Neuve, Meschers.

region. Other shallower cavities outside of the main ones serve as sheds for the wood which is used to cook, in earthen kettles, the soup and the fish and oysters which are found in abundance at the foot of the bank. The visitor who expects to find misery or signs of hard life in these grotto homes will be disappointed; instead, he will see people as satisfied with their lot as Diogenes was with his tub.

"If we desire to visit these grottoes, we may descend from one of the windmills by a winding path to the one called Femme neuve, because it is the newest of the group. We are welcomed with the best the proprietor has to offer. The women are busy with their washing. The smoke escapes freely through the loose planks of the sea-wall. A second chamber serves as a sleeping

Fig. 14.—Interior View of the Grotto La Femme Neuve, Meschers.

room and is furnished with two beds, a commode, and, opposite the beds, the fireplace, back to the sea, between two small glass windows. During high southwest winds the spray leaps up to the height of the caves, the rain dashes against the planks, the grottoes are inundated and made uninhabitable, and it becomes necessary to seek shelter in some of the cottages of the village.

"Another path from the windmills leads to a second grotto, where lives Father Lavigne, a bright and sprightly man of about eighty years, who makes a weekly trip to Royau and back in the same day. He receives his visitor with great courtesy, hat in hand, and shows him his two rooms, nearly bare, but commanding a fine view over the gulf and the sea. His furniture is simple but neat; and the old gentleman, who has lived here more than forty years, declares that he is quite happy, for health is left to him. His cave-life has never given him rheumatism.

"A locksmith and knife-grinder has recently established himself in a third cave, and has the love of a hermit for it. His door and window are open, showing a single room with a bed of straw on four legs, a wall-table, a few utensils, and a chair, as all the furniture. In one corner are a grindstone and a forge, the arrangement of which shows how much an ingenious man can do with the most primitive materials. The proprietor has traveled extensively in the exercise of his trade and has seen much of the world. Now, at forty years of age, he seeks rest, and the embellishment

Fig. 15.—Plan of the Grotto La Femme Neuve. Meschers: a, beds and closets; b, wash-tub; c, fireplace; f, windows; g, vertical planks forming a partition on the broad side; h, rim of vertical rocks twenty metres above the sea;- - - - edge of the floor; p, door; r, ladder ascending to the top of the cliff; t, water-hole.

of his home is his ruling desire. He communicates his plans enthusiastically to his visitors. He has planted white gilliflowers under his window, the only kind, he says, that will bear the sea winds. Next year he will plant a grape-arbor, the vines of which he will carefully protect against too severe exposures.

Fig. 16.—The Knife-grinder's Cave at Meschers.

"Other grottoes have been acquired by persons in easy circumstances, remodeled, partitioned off, and even fancifully papered. They are simply the pavilions of citizens, and there is no interest in visiting them." At the foot of the bluff on the eastern side are large regular cavities which are said to have been the refuge of Protestants during the religious wars. They were afterward converted into quarries, from which a soft shell stone was obtained. The places are still to be seen where the barges landed at the entrance of the quarries, and the older people of the country remember when they were worked.

For specimens of modern cave dwellings in the United States we might turn to the sod-houses of the Western plains, which the settlers construct for temporary shelter while waiting for a supply of lumber with which to build a more conventional if not better house. They can not, however, be classed with the permanent dwellings which this paper has held in view. As soon as the new house is done, they are turned over to the cattle and pigs, or abandoned and left to the mercy of the elements.

- ↑ Dr. Stephen D. Peet, in the American Antiquarian.