Popular Science Monthly/Volume 44/March 1894/Customs and Superstitions of the Mayans

| CUSTOMS AND SUPERSTITIONS OF THE MAYAS. |

By Mrs. A. D. LE PLONGEON.

FROM ancient Maya books and inscriptions we learn that the Mayas at one time formed a great nation, occupying the territory between Tehuantepec and Darien. To-day those Indians, as they are called, live in the peninsula of Yucatan, famous for its ruins; in Guatemala, in Peten, in the Lancandon country, on the banks of the Uzumacinta River, and in the valleys between those mountains where the mysterious "land of war" is supposed to be.

Among all people, civilized and uncivilized, superstition exists, though the former are more careful to conceal their peculiar notions. The Mayas are more superstitious now than they were

Indians blasting Rocks to level a Road.

five hundred years ago, for, added to their own queer notions, they have a vast store of strange fancies imported by the Spanish conquerors. Many of the native ideas are of great antiquity, such as the belief in metempsychosis and metamorphosis. Those people hesitate before killing the most venomous reptile, if found in or near the old palaces and temples left by their ancestors, and now gradually crumbling beneath the dense foliage of tropical forests. Urge them to destroy a viper within or near those deserted halls, and they say: "Ah, no! it belongs to the Xlah-pak yum" (lord of the old walls), "whose spirit roams here." Under such circumstances they recoil from inflicting death, much as they would if told to murder their father or mother—a thing unheard of among them, for they revere and honor their parents above all others. To their elders they show much respect, never presuming to contradict them beyond remarking, if they do not agree with what is said, "So says my elder," implying that but for that they would express an opinion.

When questioned about the old ruined cities, they reply, "The dwarfs built them," and insist that the pixan, or souls of those dwarfs, always walk about at night, coming into their houses, though the doors be shut. In the daytime they are supposed to dwell among the ruins. The reputation of the alux (dwarfs) is not much better than that enjoyed by the "little people" of Ireland and Scotland, accused of stealing butter, souring milk, and changing pretty babies for ugly little creatures with wrinkled faces. The alux are said to disturb tired laborers by shaking their hammocks, lash those who slumber too heavily, throw stones, and whistle. They terrify all who look at them, and steal food;

School of Mestizas Girls at Hoctam.

for, though not taller than a child four years old, they can eat more than any man does. Their only article of apparel is a very wide brimmed straw hat.

Belief in these dwarfish apparitions is perhaps induced by a vague knowledge that several centuries ago a race of remarkably small people did live in those parts. Edifices built by them are found on the east coast of Yucatan and on adjacent islands. There are several temples only nine feet high, and triumphal arches of the same height, while the doorways are but three feet high and eighteen inches wide. In some of those houses domestic utensils have been found, very small. Any traveler may examine the strange little houses; and doubtless the belief in the phantom

Southeast Corner of North Wing of Can's Palace, Uxmal.

alux is an outgrowth of tradition concerning the dwarfish people who constructed them.

Directly opposed to the alux is Huahuapach, a gigantic specter supposed to put himself in the way of belated travelers and make them fall so as to injure themselves. This, again, would be some dim recollection of those big men whose bones have at various times been unearthed in different parts of the peninsula. Several historians testify to such gigantic remains having been dug from the ground in the early part of the Conquest, We have also been assured by people of Spanish descent, now living in that country, that they themselves have disinterred enormous skulls and other bones of the human body. None had the curiosity to keep them. To this may be added that on the walls of certain ancient structures there are imprints, eleven inches long, of hands that had been dipped in red liquid and pressed upon the stones, as it was customary for the owner of the building to do.

Xtabai is a wicked, deceitful phantom, said to haunt the highways at night. It appears as a beautiful woman, always combing her luxuriant locks with a plant that the natives call "the comb of Xtabai." This lovely being generally runs away when any one approaches, but, if a lovesick laddie does succeed in clasping her in his arms, she instantly transforms herself into a sack of thorns that rests on two duck's feet. After embracing this prickly arrangement the deluded youth is ill with fever.

Another much-dreaded nocturnal, unsubstantial individual is Balam, god of agriculture, an old fellow with a long beard, said to walk in the air and whistle as he goes. Should his people fail to make offerings to him, he would vent his spleen by afflicting them with sickness; therefore, the first fruits of the field are for him. The corn first ripe is scattered upon the ground, and pies, the crust made of corn, are also prepared for the god to enjoy at his leisure. These pies are seasoned with enough red pepper to torment the palate of any number of balams (leopards). One pie is put in each corner of the field, three being sprinkled with a liquor called balché. The fourth is left without this sauce, possibly for the benefit of any teetotaler friend who may happen to call.

Balché is a liquor made by soaking the bark of a tree thus named in a mixture of honey and water. When fermented and kept some time it is very intoxicating. The Indians use it in all their ancient rites and ceremonies, and the Fans of equatorial Africa make liquor in the same way.

Catholics in name, the Mayas in fact prefer to render homage to any stone figure that once ornamented the temples of their forefathers. We have seen one, kept in a cavern underground, that served as a personification of Balam, for it represented a man with a long beard, and to it they make offerings of corn. As a work of art the figure is worthy of notice. Its antiquity can not be doubted, similar ones being sculptured on pillars at the entrance of a very ancient castle in the famous ruined city of Chichen. The figure in the cavern is on its knees; its hands are raised to a level with the head, palms upturned. On its back is a bag containing a cake of corn and beans, the whole cut from one block of stone. This statue is now black, owing to the incense and candles with which its devotees smoke it. Previous to sowing grain they place before it a basin of cool beverage made of corn, also lighted wax candles and sweet-smelling copal, imploring the god to grant them an abundant harvest. When the crops ripen the finest ears are carried to the smoke-begrimed divinity by men, women, and children, who within the cavern dance and pray all day long, some of their quaint instruments serving as accompaniment to the Christian litanies which they chant without having the vaguest idea of their meaning.

An instrument that they use in their religious practices is the tunkul. The literal meaning of this word is "to be worshiping." The tunkul is a piece of wood three feet long and one in diameter, hollowed out. On one side it has a mouth extending nearly from end to end; on the other are two oblong tongues starting from the extremities and separated in the middle only by the thickness of a carpenter's saw. Its mouth is placed in contact with the ground, and the tongues, serving as two keys, are struck with sticks whose ends are covered with India rubber, which makes them rebound. The tones thus produced can be heard five or six miles off, when the wind is favorable, and sound like a great rumbling in the earth. The same instrument was used in Mexico.

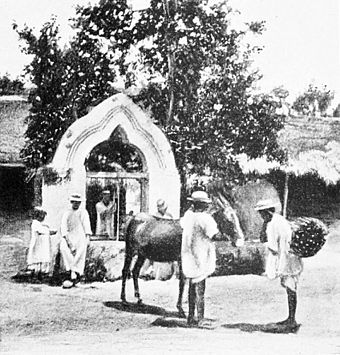

A Well by the Wayside.

In the museum of the capital of that republic some finely sculptured tunkuls are preserved.

The Maya Indians take a great deal of pleasure in ceremonies and religious observances; religion is a very important matter with them, though it is doubtful if they could tell exactly what they believe. They punctually attend church, but their worship is in reality an odd mixture of paganism and Christianity. Being fond of sweet things, and by nature indolent, their idea of heaven is a place where they will rest beneath the spreading branches of an evergreen tree and enjoy an inexhaustible supply of sweet things; while hell is a region where they will suffer intensely from cold, fatigue, and hunger. Nor do they hope to escape that torment, for it is their belief that when death claims them they will be conducted to the gloomy abode to suffer for all the wrong they have done, after which they will be in heaven for a time as a recompense for their good deeds; that then—some ages having elapsed—they must be reborn on this earth, without any recollection of the past or knowledge of the future.

When one is dangerously ill, his relations make offerings to the yumcimil, or "god of death." This offering consists of food

A Tunkul

and drink, which they hang outside of the house. They call it kex, or "exchange," because they offer it as a ransom for the life of the patient.

From remote times they have been accustomed to make offerings to the souls of the departed, particularly a certain pie that they call "food for the soul." The crust must be of yellow corn; the interior, tender chicken and small pieces of pork. These pies are wrapped in leaves of the banana tree and baked underground between hot stones. When done, they are placed on the graves or hung from trees close by. Sometimes, after leaving them there for an hour or two, the living take home the pies and enjoy them, saying that the souls have already drawn from them all the ethereal part of the substance.

When among the ruins in the ancient city of Chichen Itza, we happened to be very hard pressed for food on All Saints day, as on many other occasions, and knowing that the "feast of the dead" would be celebrated in a not very distant village, we allowed some of our men to go there and take their chance of enjoying a good meal.

In that they were most successful, the natives being at all times exceedingly hospitable, and never failing to invite those who approach their home to partake of what they have. But the men also thought of us. We had early taken to our hammocks, remembering the saying, "Qui dort, dîne" (He who sleeps, eats). About two o'clock in the morning we were aroused by a man only just returned from the village. He had waited there till all were asleep, then made his way to the graveyard, and gathered from a tree a fine fruit in the shape of a large pie. This he brought to us, wisely arguing that the embodied needed it more than the disembodied. The dead man's food was still wrapped in its banana leaf, and we were not sorry to avail ourselves of this chance to breakfast at two o'clock in the morning. No tender chicken was concealed within that particular crust, only a pig's foot with a few stray bristles on it, and a most liberal dose of red pepper, but hunger made it excellent.

When overtaken by disease, the Indians doctor themselves with certain herbs, and if that fails, call a medicine man, who knows about as much of their malady as they themselves do—perhaps less. They never attribute illness to natural causes, but either declare that they are bewitched or that their time has come and Death wants them. The medicine man pretends that he can discover the party who has done the bewitching, and for that purpose demands three days' meditation in the home of the patient, during which time he must be supplied with all the good food and drink procurable. On the third day he drinks balché, nectar of the gods, until he falls into a heavy sleep. The instant he awakes he looks into a crystal and there pretends to see the witch or wizard. He then scrapes the mud floor under the hammock of the patient, and produces a small figure that he, of course, had concealed about his person, and declares that that was what caused the sickness. For this simple trick he receives a fee. If the patient recovers, the medicine man's reputation is greatly increased. If death results, the mourners say: "It is very hard, but so it was written; his time had come; it had to be thus."

The little figures used by the trickster are made of wax and have a thorn stuck in the part corresponding to the seat of greatest pain in the body of the victim. This particular superstition may therefore have been introduced by the Spaniards, for at one time l'envoútement was believed in nearly all over Europe; even yet credence is given to it among voodoo societies in Louisiana. L'envoútement consists in pricking and slowly melting a small wax figure representing the individual intended for a victim of magic art. Charles IX, of France, was said to have come to his

Indian Women spinning.

death by means of wax figures made to his likeness and cursed by magic art which his enemies, the Protestant sorcerers, caused to melt, a little every day, thus extinguishing the life of the king by degrees as the figures were consumed.

That same monarch is said to have expelled thirty thousand sorcerers from the city of Paris; and during the reign of Henry III, France was supposed to be infested with one hundred thousand individuals who practiced the black art. Physicians in those days made the sorcerers responsible for all diseases that they failed to cure. Consumptives especially were supposed to waste away as the wax figures did when melted.

In former times the Indians used to abandon a house after one died in it, because they buried the body either in the house or at the back of it, and were very much afraid of seeing the ghost of the dear departed. Strange creatures, to weep so much at losing them, and then be terrified at the thought of their returning!

They believed that the lower animals also had souls, for they used to put with the corpse of their relations certain provisions which they said was to feed the souls of the animals they had eaten during life, so that these might not harm them.

They bred a species of dog, quite hairless, called tzom, considered a great delicacy. They killed them by choking them in a pit, and this seems to have weighed heavily on their conscience, for they were particularly careful to provide deceased relations with food to pacify the slaughtered tzoms.

Being constant and careful observers of Nature, and seeing the remarkable works of many creatures, they attribute intelligence to small insects, such as the ants and bees. In some parts of England it is supposed that bees will not remain on the premises after there is a death in the house of their owner, unless an intimation of the fact be conveyed to them. Therefore some go and tell the bees; others tie a piece of crape to a stick, and set it in front of the hives.

The Indians in question would not tie crape near their hives, for they themselves never use any kind of mourning, retaining always their white garments. They suspend from the hives gourds filled with a beverage made from corn, in order that the bees may not go away, but produce abundant honey and keep sickness from the home. The hives are not like those in use among us, but simply pieces of trunk hollowed out, wooden walls being fitted into the ends and covered with mud so that the name

A Yucatan Village.

of the owner may be stamped on it with white ashes. A small hole is left in the middle of each end for the passage of the bees. If the hives are not cleaned from time to time, the bees desert them. In order to do this, the operator removes the end walls, cleans the interior thoroughly, and rubs it with a little honey and an aromatic plant that is much liked by the bees. Unlike our bees, these are quite harmless, black and small, though they manifest their annoyance when intruded upon, by swarming about ones head, getting into hair, ears, eyes, and nose. After their hives are cleaned they make no mistake as to their homes, every insect returning with unerring precision to its own quarters. At each entrance a bee sentinel constantly stands, to give warning of approaching danger, when, from within, the door is immediately blockaded.

We must not forget to mention the Ez, the genuine wizard, supposed to call to his aid the black art for evil purposes, whereas the medicine man is believed to be a good magician. The Ez may and does "bewitch" those who offend him, but the medicine man can break the spell. They are very careful to make this distinction between magician and sorcerer.

While in the eastern part of Yucatan, we frequently heard people speak of the Jew's Book, a medical work bearing that title. At last it fell into our hands—not a printed copy, though it has been put in type, but the old Spanish manuscript. The contents rather astonished us. As a cure for leprosy, patients are advised to drink the water in which an unplucked turkey buzzard has been boiled for three hours!

However, we found some very important recipes. Here, for instance, is one to cure the bewitched: "First take a root of vervain, cook it in wine and make the patient drink it. This will be thrown up. To know if the person is bewitched, pass over him a branch of the plant called skunk. If the leaves turn purple, the patient is bewitched. To free him from the enchantment, let him wear a cross made from the root of the skunk plant." The odor of that plant would most undoubtedly remove all charm from any person!

Side by side with those absurd prescriptions, there are others quite in accordance with the materia medica. The book is believed to have been written by a white man, and many white people and half-breeds have the greatest confidence in it. As for the Indians, they summon the medicine man to give them herbs and dispel the evil power of the wizard that has prostrated them.