Popular Science Monthly/Volume 45/October 1894/Sketch of Asaph Hall

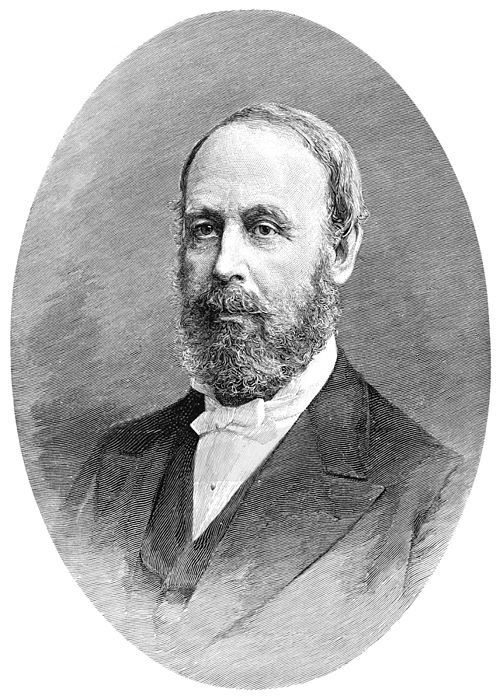

| SKETCH OF ASAPH HALL. |

IN spite of the few wonderful accidents that have led to great changes and advance in modern ideas, most of the real advances of the world have been the results of simple hard work and hard thinking by men of ability. As an example of the type of scientist who does not make astounding discoveries of doubtful value, but who surely and steadily advances the cause of science by faithful work, stands the astronomer Asaph Hall.

He was born on October 15, 1829, in the little town of Goshen, in the northwestern part of Connecticut, where the Berkshire Hills come rolling over from Massachusetts. His grandfather, a Revolutionary officer, was one of the first settlers of the place, and was a wealthy man. But his father, through business failures, lost nearly all his property. In 1842 he died, leaving a wife and six children, of whom Asaph, then thirteen, was the oldest. Up to the time of his father's death Asaph's life was that of a well-to-do country boy. He had worked on the farm and he had gone to the village school. His father was far better educated than most of the men of the place, so that many good books fell into the boy's hands. Often his rainy days were spent in the garret, fighting the battles on the plains of Troy, or following Ulysses in his wanderings.

When his father died everything was changed. Almost all the property was mortgaged. In a family council it was decided to remain on one of the farms and try to pay off the mortgage. So Asaph and his mother set to work, and for three years toiled with might and main, carrying on the work of a large farm almost entirely by themselves. Asaph's mother was a tireless worker, and he helped her as best he could; but when the three years were past they found they had been able to pay the interest on the mortgage and nothing more. Sticking to the farm did not seem to pay, so Asaph decided to leave and go and learn the carpenter's trade. He persuaded his mother to move to a little place she owned free from debt, and he apprenticed himself to a local carpenter. He worked for three years for sixty dollars a year. At the end of that time he became a journeyman and worked for himself. He stayed in Litchfield County, helping to build houses and barns that are standing on the old farms to-day.

For six years he stuck to carpenter work, but all that time he was full of ambition. He saw that the men he worked with were a poorly educated set. They knew how to make a right angle by the three, four, five rule, but they had no idea at all of the reason for it. He was not satisfied to work in this blind rule-of-thumb fashion—he wanted to know the reasons of things; so he kept picking up some knowledge of mathematics to help him understand his business. In the summer he was busy with carpenter work, but in the winter he generally went home. He did the chores on the farm in the early morning and at night, and went to school besides. As he learned more he decided to study and become an architect. He managed to spend one winter in Norfolk, Conn., under the instruction of the Principal of the Norfolk Academy. There he went through algebra and six books of geometry.

When he was twenty-five years old he had saved a little money from his carpenter work. Through the New York Tribune he saw that there was a college at McGrawville, N. Y., where a young man could earn his living and get an education at the same time. He decided to go to this college. So in the summer of 1854 he set out for Central College, as it was called. When he got there he found it was a very different place from what he had expected. It was open to both sexes and all colors, and was the gathering place of a queer set of cranks of all sorts. The teaching was poor, but still to the green country youth the experience was of immense value. His views were broadened and changed. He stayed at the college only a year and a half. In that time he went through algebra, geometry, and trigonometry, and studied some French and Latin. He soon proved himself to be by far the best mathematician in the college.

One of the students was a young woman named Angeline Stickney. She was a country girl of great sensibility and of fine mental qualities. She was working her way through college, and as a senior she helped in the teaching. Asaph Hall was one of her pupils in mathematics. Many were the problems he and his classmates contrived to puzzle their teacher, but they never were successful. When she was graduated Asaph Hall was engaged to her. He decided that he had stayed long enough at McGrawville. His money was about gone, and the college was poor. So in 1855 they set out together for Wisconsin. Angeline Stickney had a brother there, and she stayed at his house while Asaph tramped about the country in search of a school where they could teach. No school was open for them. They became tired of the flat, sickly country, and when spring came they decided to leave. On the 31st of March, 1856, they were married. Then they started for Ann Arbor. Asaph entered the sophomore and junior classes in Ann Arbor University, studying mathematics and astronomy under Prof. Brünnow. He found he could do good work in both these branches. His teacher encouraged him greatly. It was from him that he acquired his taste for astronomy. Prof. Brünnow was an excellent teacher, but he had trouble with his classes, and his work was so changed and broken up that young Hall decided to leave after he had been there but half a year.

He went with his wife to Shalersville, Ohio, and took charge of the academy there. They conducted it successfully for a year, paying off all their debts and buying themselves new clothes, of which they were much in need. When the school was over they had no idea where to turn next. Hall wanted to go back to Ann Arbor and study again, but there was a great storm on the lakes at that time and his wife would not go. So they started East. He had had an offer from Prof. Bond, who was in charge of the Harvard College Observatory, of three dollars a week as assistant. Finally, he decided to accept it. He visited his old home in the summer, and in the fall of 1857 he took his wife to Cambridge and began his career as an astronomer.

Very few young married men of this day would like to start in a profession at the age of twenty-nine on a salary of three dollars a week. But young Hall expected he would be able to pick up outside work. He thought he could pursue his study in mathematics under Prof. Benjamin Peirce, then at Harvard. So he entered on his new life full of hope. He took a couple of rooms on Concord Avenue, near the observatory, and began housekeeping. He soon found he could not carry out all his plans. There was some quarrel between Prof. Peirce and Prof. Bond, and he could not study with the former without offending his employer. He had to give up that plan. His work at the observatory required long hours, but he managed to study a little by himself. He studied mathematics and German at the same time by translating a German mathematical work. His little income was all eaten up by simply the room rent. In order to live he had to do outside work. By computing, making almanacs, and observing moon culminations he doubled his salary and managed to scrape along. His wife worked by his side faithfully, encouraging him, helping him in his studies, and doing all the housework with her own hands. Hall soon became a rapid, accurate, and skillful computer. Soon his employers saw how valuable he was, and they gradually increased his pay, till at last he drew a salary of six hundred dollars a year.

He stayed in the Cambridge Observatory till the year 1862. At that time the war had been going on for a year. The officers at the Naval Observatory at Washington had gone off into the service of either the North or the South. Men were needed to fill their places. Hall was recommended to fill a position there. It was a good opening. He went to Washington, passed an examination, and was offered a place. In the fall of 1863 he went down to Washington to begin his work. The city was then in a ferment. Many of the officeholders were from the South. All sorts of jealousies and meanness were rife in the departments of the Government. But he kept out of all disputes and settled down quietly to his work.

On January 2, 1863, he was appointed a Professor of Mathematics in the United States Navy. After that his career was assured, for his position was for life. Starting as a farmer boy, then turning carpenter, pursuing mathematics with the idea of becoming an architect, finally he had found the best field for his labor in astronomy. Up to this time his struggle was a hard one. He had never known what it was to have a moment of relaxation. It was toil from morning till night, and all that he did was for the personal benefit of others. After his appointment at Washington he was able to do work that counted for himself. So his public scientific career really began in 1862.

From 1862 to 1866 he worked on the nine-and-a-half-inch equatorial at the Naval Observatory under Mr. James Ferguson, making observations and reducing his work. One night, while he was working alone in the dome, the trap-door by which it was entered from below opened, and a tall, thin figure, crowned by a stovepipe hat, arose in the darkness. It turned out to be President Lincoln. He had come up from the White House with Secretary Stanton. He wanted to take a look at the heavens through the telescope. Prof. Hall showed him the various objects of interest, and finally turned the telescope on the half-full moon. The President looked at it a little while and went away. A few nights later the trapdoor opened again, and the same figure appeared. He told Prof. Hall that after leaving the observatory he had looked at the moon, and it was wrong side up as he had seen it through the telescope. He was puzzled, and wanted to know the cause, so he had walked up from the White House alone. Prof. Hall explained to him how the lens of a telescope gives an inverted image, and President Lincoln went away satisfied.

After 1866 Prof. Hall worked as assistant on the prime vertical transit and the meridian circle. In 1867 he was put in charge of the meridian circle. From 1868 to 1875 he was in charge of the nine-and-a-half-inch equatorial, and from 1875 until his retirement on October 15, 1891, he was in charge of the twenty-six-inch equatorial. It can thus be seen that his practical experience as an observing astronomer has been long and varied.

During his stay at the observatory he was sent on several expeditions for the Government, In 1869 he was sent to Bering Strait on the ship Mohican to observe an eclipse of the sun. In those days one had to go to San Francisco by way of the Isthmus of Panama; all the instruments had to be sent the same way so it was a big undertaking. In 1870-'71 he was sent to Sicily to observe another eclipse. In 1874 he went to Vladivostock, in Siberia, to observe a transit of Venus. He visited China and Japan on the way. In 1878 he headed an expedition to Colorado to observe the eclipse of the sun, and in 1882 he took a party to Texas to observe another transit of Venus.

Although on these expeditions he did valuable service, it has been at Washington with the twenty-six-inch equatorial that he has done his most important work. He has made studies of many double stars, to determine their distances and motions. He has also given a great deal of time to the study of the planet Saturn. He made an especial investigation of the rings of this planet, and also discovered the motion of the line of apsides of Hyperion, one of Saturn's satellites. But by far the most important discovery he has made, the one that will connect his name with astronomy as long as the planets exist, was his discovery of the satellites of Mars. It had been thought by some old astronomer that perhaps Mars had satellites, but no one had been able to find them. In the fall of 1877 Mars was in a very favorable position to observe, and Prof. Hall turned his big telescope upon it. He searched night after night without finding anything new. He began to give up hope; but on the night of August 11th he discovered a little speck that turned out to be the outer satellite. Six days later he discovered the inner one. The discovery of these two little bodies (the smaller one being not more than fifteen miles in diameter) spread quickly among the observatories. The eager astronomers immediately began to find enough extra moons to supply another solar system. One observer insisted that there was one more moon at least, and Prof. Hall was blamed as stupid for not seeing it. But after a thorough investigation it was shown that Prof. Hall had discovered the two and the only two satellites of Mars,

This important discovery brought his name at once before the world at large, and was not slow in earning its reward. The Royal Astronomical Society presented him with a gold medal, and he was given the Lalande prize from Paris. Since that time his work has been recognized as it should. He has become a member of the most important scientific societies of this country, and an honorary member of the royal scientific societies of England and Russia and of the French Academy. The universities of the country have recognized his work, Yale and Harvard each giving him the degree of LL. D. The very last honor conferred upon him is the Arago medal, just awarded to him by the French Academy of Sciences.

Personally, Prof. Hall is a fine-looking man. He is tall and broad-shouldered. His forehead is high and deep. His eyes are clear and bright, in spite of years spent in gazing at the stars. He has always been strong and healthy. He is fond of the open air, and has always taken exercise. So, in spite of his long years of hard work, he is now in perfect health. His success has not changed him in the least. He is always ready to help those who want to learn anything from him.

His writings have appeared mainly in astronomical magazines and in the Government reports of the work done in the Naval Observatory. They are all the results of practical astronomical work, and are mostly of a technical character. Consequently, they are of little interest to general readers. He has often been asked to write something for popular reading, but up to this time he has never consented to do so, thinking that there is already enough of such literature.

Prof. Hall is a self-made man. His life has not been an easy one. Every bit of his education, every one of his successes, has been gained by his own hard work. It was a steady uphill pull from the time he was thirteen years old until his appointment at Washington. In his younger days he saw many hard times. During a large share of that part of his life he had only one good suit of clothes in his possession. He and his wife were obliged to save every penny. From his early training and from such experience his habits were formed. Naturally they are of the simplest kind. He does not care for the luxuries of modern life. The comforts of a plain home are all he wants. He still lives almost as simply as when he was earning three dollars a week under Prof. Bond. He has never cared for society merely for its own sake, but he has been prominent in scientific circles. He is a quiet man who never pushes himself forward; yet, when he has anything to say, people are glad to listen to it.

In his ideas on politics, science, and religion he is liberal and yet conservative—that is to say, he has no objection to letting other people have their own thoughts and live their own lives. He can see no reason why science and real religion can not be reconciled. His views on religion and politics are sound. He does not care, however, to have anything to do with politics. He hates its corruption, meanness, and party quarreling. He has always been a little conservative in his scientific life. He has never been led into wild theories of no value. His work has been solid, earnest, and thorough, and will last forever. He is a widely read man, fond of study. He loves his work; so now, since his retirement in 1891, he continues his studies and investigations. He lives a quiet, simple life at his home in Washington, still advancing the cause of astronomy.