Popular Science Monthly/Volume 51/October 1897/The Racial Geography of Europe: Italy IX

APPLETONS’

POPULAR SCIENCE

MONTHLY.

OCTOBER, 1897.

| THE RACIAL GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPE. |

A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY.

(Lowell Institute Lectures, 1896.)

By WILLIAM Z. RIPLEY, Ph. D.,

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY, MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY; LECTURER IN ANTHROPO-GEOGRAPHY AT COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY.

IX.—ITALY.

THE anthropology of Italy has a very pertinent interest for the historian, especially in so far as it throws light upon the confusing statements of the ancients. Pure natural science, the morphology of the genus Homo, is now prepared to render important service in the interpretation of the body of historical materials which has long been accumulating. Happily, the Italian Government has assisted in the good work, with the result that our data for that country are extremely rich and authentic[1] The anthropological problems presented are not as complicated as in France, for a reason we have already noted—namely, that in Italy, lying as it does entirely south of the great Alpine chain, we have to do practically with two instead of all three of the European racial types. In other words, the northern Teutonic blond race is debarred by the Alps. It does appear in a few places, as we shall take occasion to point out, but its influence is comparatively small. This leaves us, therefore, with two rivals for supremacy—viz., the broad-headed Alpine type of central Europe and the true Mediterranean race in the south.

A second reason, no less potent than the first, for the simplicity of the ethnic problems presented in Italy is, of course, its peninsulated structure. All the outlying parts of Europe enjoy a similar isolation. The population of Spain is even more unified than the Italian. The former is probably the most homogeneous in Europe, being almost entirely recruited from the Mediterranean long-headed stock. So entirely similar, in fact, are all the peoples which have invaded or, we had better say, populated the Iberian Peninsula that we are unable to distinguish them anthropologically one from another. The Spaniards are akin to the Berbers in Morocco, Algiers, and Tunis. The division line of races falls at the French-Spanish frontier, as the maps in our last article on the Basques showed in detail. "Beyond the Pyrenees begins Africa" indeed. In Italy a corresponding transition from Europe to Africa takes place, more gradually perhaps but no less surely. It divides the Italian nation into two equal parts, of entirely different racial descent.

Geographically, Italy is constituted of two distinct parts. The basin of the Po, between the Apennines and the Alps, is one of the best defined areas of characterization in Europe. The only place in all the periphery where its boundary is indistinct is on the southeast, from Bologna to Pesaro. Here, for a short distance, one of the little rivers which comes to the sea by Rimini, just north of Pesaro, is the artificial boundary. It was the Rubicon of the ancients, the frontier chosen by the Emperor Augustus between Italy proper and cisalpine Gaul. The second half of the kingdom, no less definitely characterized, lies south of this line in the peninsular portion. Here is where the true Italian language in purity begins, in contradistinction to the Gallo-Italian in the north, as Biondelli long ago proved. The boundaries of this half are clearly marked on the north along the crest of the Apennines, away across to the frontier of France; for the modern provinces of Liguria (see map) belong in flora and fauna, and, as we shall show, in the character of their population, to the southern half

of the country. It is this leg of the peninsula which alone was called Italy by the ancient geographers; or, to be more precise, merely the portion south of Rome. Only by slow degrees was the term extended to cover the basin of the Po, The present political unity of all Italy, real though it be, is of course only a recent

and, in a sense, an artificial product. It should not obscure our vision as to the ethnic realities of the case.

The topography and location of these two halves of the kingdom of Italy which we have outlined have been of profound significance for their human history. In the main distinct politically, the ethnic fate of their several populations has been widely different. In the Po Valley, the "cockpit of Europe," as Freeman termed it, every influence has been directed toward intermixture. Inviting in the extreme, especially as compared with the transalpine countries, it has been incessantly invaded from three points of the compass. The peninsula, on the other hand, has been much freer from ethnic interference, especially in the early days when navigation across seas was a hazardous proceeding. Only in the extreme south do we have occasion to note racial

invasions along the coast. The absence of protected waters and especially of good harbors, all along the middle portion of the peninsula has not invited a landing from foreigners. Open water ways have not enabled them to press far inland, even if they disembarked. These simple geographical facts explain much in the anthropological sense. They meant little after the full development of water transportation, because thereafter travel by sea was far simpler than by land. Our vision must, however, pierce the obscurity of early times before the great human invention of navigation had been perfected. In order to give a summary view of the physical characteristics of the present population which constitutes the two halves of Italy above described, we have reproduced upon the following pages the three most important maps in Livi's great atlas. Based as they are upon detailed measurements made upon nearly three hundred thousand conscripts, they can not fail to inspire confidence in the evidence they have to present. Especially is this true since their testimony is a perfect corroboration of the scattered researches of many observers since the classical work of Calori and Nicolucci thirty years ago. Researches at that time made upon crania collected from the cemeteries and crypts began to indicate a profound difference in head form between the populations of north and south. Then later, when Zampa, Lombroso, Pagliani, and Riccardi[2] took up the study of the living peoples, they revealed equally radical differences in the pigmentation and stature. It remained for Livi to present these new data, uniformly collected from every commune in the kingdom, to set all possible doubts at rest. It should be observed that our maps are all uniformly divided by white boundary lines into compartimenti, so called. These administrative districts correspond to the ancient historical divisions of the kingdom. Their names are all given

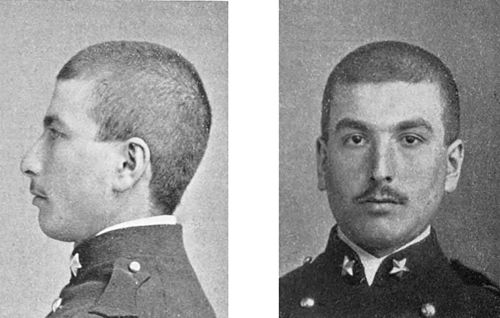

Alpine Type. Piedmont. Cephalic Index, 91·3

upon our preceding map of physical geography. Being similar through the whole series, they facilitate comparisons between smaller districts in detail.

The basin of the Po is peopled by an ethnic type which is manifestly broad-headed. This Alpine racial characteristic is intensified all along the northern frontier. In proportion as one penetrates the mountains this phenomenon becomes more marked. It culminates in Piedmont along the frontier of France. Here, as we have already shown in our general map of Europe, is the purest representation of the Alpine race on the continent. Dr. Livi has photographed a recruit from this region for me. It is reproduced upon this page. The rounded fullness at the forehead and the shortness of head from front to back can not fail of notice. Across the frontier, in French Savoy, the same racial type is firmly intrenched in the high Alps. Such is also the prevalent physical type of the Swiss, who are descendants of the Rhætians of Roman times. Still further back we come upon the prehistoric lake dwellers. No change of race has here taken place since very early times. All indications point to a primitive occupation and a persistent defense of the Alpine highland by this broad-headed racial type.[3]

This Alpine type in northern Italy is the most blond and the tallest in the kingdom. This, of course, does not imply that these are really a blond and tall people. Compared with those of our own parentage in northern Europe, these Italians appear to be quite brunette; hair and eyes in our portrait type were classed as light chestnut. Standing in a normal company of Piedmontese, an Englishman could look straight across over their heads; for they average three to five inches less in bodily stature than we in England or America; yet, for Italy, they are certainly one of its tallest types. The traits we have mentioned disappear in exact proportion to the accessibility of the population to intermixture. The whole immediate valley of the Po, therefore, shows a distinct attenuation of each detail. We may in general distinguish such ethnic intermixture from either of two directions: from the north it has come by the influx of Teutonic tribes across the mountain passes; from the south, by several channels of communication across or around the Apennines from the peninsula. For example, the transition from Alpine broad heads in Emilia to the longer-headed population over in Tuscany near Florence is rather sharp, because the mountains here are quite high and impassable, save at a few points. On the east, however, by Pesaro, where natural barriers fail, the northern element has penetrated farther to the south. It has overflowed into Umbria, Tuscany, and Marche, being there once more in possession of a congenial mountainous

habitat.[4] The same geographical isolation which, as Symonds asserts, fostered the pietism of Assisi, has enabled this northern type to hold its own against aggression from the south. It is rather interesting to note the prevalence of the brachycephalic Alpine race in this mountainous part of Italy; for nowhere else in the peninsula proper is there any evidence of that differentiation of the populations of the plains from those of the mountains which we have noted in other parts of Europe. Nor is a reason for the general absence of the phenomenon hard to find. If it be, indeed, an economic and social phenomenon, dependent upon differences in the economic possibilities of any

given areas, there is little reason for its appearance elsewhere in Italy; for the Apennines do not form regions of economic unattractiveness, as their geology is favorable to agriculture, and their soil and climate are kind. In many places they are even more favorable habitats than the plains, by reason of a more plentiful rainfall. The absence of anthropological contrasts coincident with a similar absence of economic differences is, in fact, a point in favor of our hypothesis.

Are there any vestiges in the population of northern Italy of that vast army of Teutonic invaders which all through the historic period and probably since a very early time has poured over the Alps and out into the rich valley of the Po? Where are those gigantic, tawny-haired barbarians described by the ancient writers who came from the far country north of the mountains? Even of late there have been many of them—Cimbri, Goths, Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Saxons, Lombards. Historians are inclined to overrate their numerical importance as an element in the present population. On the other hand many anthropologists, Virchow for example, have asserted that these barbarian invaders have completely disappeared from sight in the present population. Truth lies intermediate between the two. It is, of course, probable that ancient writers exaggerated the numbers in the immigrant hordes. Modern scholars estimate their numbers to be relatively small. Thus Zampa[5] holds the invasion of the Lombards to have been the most considerable numerically, although their forces did not probably exceed sixty thousand, followed perhaps by twenty thousand Saxons. Eighty thousand immigrants in the most thickly settled area in ancient Europe surely would not have diluted the population very greatly. We can not expect too much evidence in this direction consequently, although there certainly is some. The relative purity of the Piedmont Alpine type compared with that of Veneto is probably to be ascribed to its greater inaccessibility to these Teutons. Wherever any of the historic passes debouch upon the plain of the Po there we find some disturbance of the normal relations of physical traits one to another; as, for example, at Como, near Verona, and at the mouth of the Brenner in Veneto. The clearest indubitable case of Teutonic intermixture is in the population of Lombardy about Milan. Here, it will be observed on our maps, is a distinct increase of stature; the people are at the same time relatively blond. The extreme broad-headedness of Piedmont and Veneto is moderated. Everything points to an appreciable Teutonic blond. This is as it should be. Every invading host would naturally gravitate toward Milan. It is at the focus of all roads over the mountains. Ratzel, in his Anthropo-Geographie, has contrasted the influence exerted by the trend of the valleys on the different slopes of the Alps. Whereas in France they all diverge, spraying the invaders upon the quiescent population; in Italy all streams seem to concentrate upon Lombardy.[6] The ethnic consequences are apparent there, perhaps for this reason. With the exception of Lombardy the blood of the Teutonic invaders in Italy seems to have been diluted to extinction. Notwithstanding this, it is curious to note that the German language still survives in a number of isolated communities in the back waters of the streams of immigration. Up in the side valleys along the main highways over the Alps are still to be found German customs and folklore as well. The peasants, however, are not to be distinguished physically at this present day from their true Italian-speaking neighbors. These southern Alps are also places of refuge for many other curious membra disjecta. Mendini, for example, has studied in Piedmont, with some detail, a little community of the Valdesi, descendants of the followers of Juan Valdès, the mediæval reformer. Here they have persisted in their heretical beliefs despite five hundred years of persecution and ostracism. In this case mutual repulsion seems to have produced real physical results, as the people of these villages seem to differ quite appreciably from the Catholic population in many important respects.

The ethnic transition from the Alpine race in the Po Valley to the Mediterranean race in Italy proper is particularly sharp along the crest of the Apennines from the French frontier to Florence. The population of modern Liguria, the long, narrow strip of country between the mountains and the Gulf of Genoa, is distinctly allied to the south in all respects. Especially does the Mediterranean long-headedness of this region appear upon both of our maps of cephalic index. It is curious to note how the sharpness of the ethnic boundary is softened where the physical barriers against intercourse between north and south are modified. Thus there is just north of Genoa a decided break in the distinct racial frontier of the province; for just here is, as our topographical map of the country indicates, a broad opening in the mountains leading over to the north. The pass is easily traversed by rail to-day. Over it many invasions in either direction have served to confound the populations upon either side.

The individuality of the modern Ligurians culminates in one of the most puzzling ethnic patches in Italy, viz., the people of the district about Lucca, in the northwest corner of Tuscany. Consideration of our maps will show the strong relief with which these people stand forth from their neighbors. These peasants of Garfagnana and Lucchese seem to set all ethnic probabilities at naught. They are as tall as the Venetians or any of the northern populations of Italy, yet in head form they are closely allied to the people of the extreme south. They are among the longest-headed in [all the kingdom. They seem also to be considerably more brunette than any of their neighbors. Nor are these peculiarities of modern origin; certainly not their stature, at all events. For Strabo tells us that the Romans were accustomed to recruit their legions here because of the massive physique of the people.

In order to make the reality of this curious patch more apparent, we have reproduced in our small map on this page a bit of the country in detail. It shows how suddenly the head form changes at the crest of the Apennines as we pass from the Po valley to the coast strip of Liguria. As we leave the river and rise slowly across Emilia toward the mountain range the heads

gradually become less purely Alpine: and then suddenly as we cross the watershed we step into an entirely different population. On the southern edge this little spot of Mediterranean longheadedness terminates with almost equal sharpness, although geographical features remain quite uniform. This eliminates environment as an explanation for the phenomenon; we must seek the cause elsewhere.

All sorts of explanations for the peculiarities of this ethnic spot about Lucca have been presented. Lombroso, who first discovered its tall stature, inclines to the belief that here is a last relic of the ancient and long-extinct Etruscan people penned in between some of the highest mountains in Italy and the sea. He holds that they were here driven to cover in this corner of Tuscany by the developed Roman power in the south. Dr. Beddoe gives another explanation which is interesting. He believes this population to be the result of artificial colonization. Livy tells us that the Romans at one time, in pursuance of a long-settled policy, transported forty thousand Ligurians (?) to Samnium, filling their places with others from the south. If this artificial transplanting had been effected a sufficient number of times; if the Liguria of Livy had surely been this modern one instead of the Alpine ancient one; and thirdly, if we could thus account for the tallness of stature, certainly not of southern origin, we might place more reliance upon this ingenious hypothesis. As it is we can not think it far reaching enough. To us it seems more likely that we have to do rather with a population highly individualized by geographical isolation. Much of the region is very fertile; it is densely populated; it is closely bounded by mountain and sea. May it not contain a remnant of a more ancient people than others roundabout? This accords with both Sergi's and Livi's view. At a later time we shall be able to prove that in many respects the oldest, most primitive layer of population in Italy possessed many of these peculiar traits of the Garfagnanans and Luccheser. We incline to the belief that a bit of this primitive substratum has persisted in this place. The people of the island of Elba off the coast are quite similar to it. Insularity explains their peculiar physical traits. Why not environmental isolation about Lucca as well?

One of the most disputed points in the ethnological history of Europe concerns the origin of the ancient Etruscans, who dominated middle Italy a thousand years or more before the Christian era. Ancient Etruria covered what is now made up of the two compartimenti of Toscana and Roma—extending, that is to say, from the Arno to the Tiber. Here we find a sub-area of characterization, rich alike in soil and climate, somewhat isolated from the rest of the peninsula. This district is the center of one of the earliest highly evolved cultures in Europe. The Etruscans appear suddenly upon the scene, invading the territory of the Umbrians, who seem to have been indigenous to the soil, akin to the Oscians, Italians (Vituli), and other native peoples. With the advent of this immigrant people a great advance in culture seems to have occurred, from which Rome afterward derived her supremacy in that respect: for the Etruscans were the real founders of the Eternal City.

Popularly, the word "Etruscan" at once suggests the ceramic art; the progress effected in a short time was certainly startling. To give an idea of the sudden change, we have reproduced upon this page illustrations of typical bits of Italian pottery. The first vase, prior to the full Etruscan culture, shows its crudity at once, both in its defects of form and the plainness and simplicity

| Early Etruscan. | Pure Etruscan. Middle Period. |

of its ornamentation. Such a vessel might have been made in Mexico or even by our own Pueblo Indians. In a century or two some teacher made it possible to produce the sample depicted in the next cut. Perfect in form, superb in grace of outline, its decoration is most effective; yet it betrays greater skill in geometrical  Greek Etruscan. design than in the representation of animate life. The dog drawn on the girdle is still far from lifelike. Then come—probably after inspiration from Greek art—the possibilities in complex ornamentation represented by our third specimen. Not more pleasing in form; perhaps less truly artistic because of its ornateness, it manifests much skill in the delineation of human and animal forms. The culture culminates at this point. From profusion of ornament and overloaded decoration degeneracy begins. It is the old story of the life and decay of schools of art, time in and time out, the world over.

Greek Etruscan. design than in the representation of animate life. The dog drawn on the girdle is still far from lifelike. Then come—probably after inspiration from Greek art—the possibilities in complex ornamentation represented by our third specimen. Not more pleasing in form; perhaps less truly artistic because of its ornateness, it manifests much skill in the delineation of human and animal forms. The culture culminates at this point. From profusion of ornament and overloaded decoration degeneracy begins. It is the old story of the life and decay of schools of art, time in and time out, the world over.

The advance in culture typified by our vases was equaled in all the details of life.[7] The people built strongly walled cities; they constructed roads and bridges; their architecture, true predecessor of the Roman, was unique and highly evolved. All the plain and good things of life were known to these people, and their civilization was rich in its luxury, its culture and art as well. In costumes, jewelry, the paraphernalia of war, in painting and statuary they were alike distinguished. Their mythology was very complex, much of the Roman being derived from it. Most of our knowledge of them is derived from the rich discoveries in their chambered tombs, scattered all over Italy from Rome to Bologna. There can be no doubt of a very high type of civilization attained as early as ten or twelve centuries before the Christian era. Roman history is merged in the obscurity of time, five or six hundred years later than this. The high antiquity of the Etruscan Is therefore beyond question.

We know less of the language used by the Etruscans than of many other details of their existence—only enough to be assured that it was of an exceedingly primitive type. It was constructed upon as fundamentally different a system from the Aryan tongues as is the Basque, described in our last paper. It seems to have been, like the Basque, allied to the great family of languages which includes the Lapps, Finns, and Hungarians in modern Europe, and the aborigines of Asia and America. These unfortunate similarities led to all sorts of queer theories as to the racial origin of the people; as wild, many of them, as those invented for the Basques. It never occurred to any one to differentiate race, language, and culture one from another, distinct as each of the trio may be in our eyes to-day. If a philologist found similarity in linguistic structure to the Lapp, he immediately jumped to the conclusion that the Etruscans were Lapps, and Lapland the primitive seat of the civilization. Thus Taylor, in his early work, asserts an Asiatic origin akin to the Finns. Then Pauli and Deecke for a time independently traced them to the same Turanian source. At last, when the Etruscan civilization began to be investigated in detail, authorities fell into either one of two groups. They both agree that the culture itself was of foreign origin. The Germans, with the sole exception of Pauli[8] and Cuno, are unanimous in the assertion that it is an immigrant from the Danube Valley and northern Europe. These authorities regard it as an offshoot of the so-called Hallstadt civilization, which flourished at a very early period in this part of the continent. In a later paper on the Aryan culture we shall have occasion to speak of it more in detail. At the same time they declare the people racially to be of Rhætian or Alpine origin. The second school is disposed to derive the Etruscan civilization from the southeast—generally Lydia in Asia Minor. The relation of the Etruscan to the Greek is by them held to be very close.[9] Much evidence is favorable to either side. To us it seems that Deecke is more nearly correct than either. He holds it to be probable that both centers of civilization contributed to the common product. In his opinion the Etruscans were crossed of the Tyrrhenians from Asia Minor and the Raseni from the Alps. All these views, it will be noted, concern civilization mainly. It is now time for us to examine the purely physical data at our disposition. Even supposing their culture to have been an immigrant from abroad, that need not imply a foreign ethnic derivation for the people themselves.

Inspection of our maps, in so far as they concern Etruria, convinces one that if the Etruscans were of entirely extra-Italian origin, their descendants have at the present time completely merged their identity in that of their neighbors; for no sudden transitions are anywhere apparent, either in respect of head form, stature, or pigmentation. On the whole, the trend of testimony appears to favor the German theory that the Etruscans made a descent upon Italy from the north; and that they were derived from the Rhætians, racial ancestors of the modern Swiss andother Alpine peoples. Thus it will be observed that Tuscany allies itself in head form to the north rather than the south. Especially is this brachycephaly noticeable about Bologna, just over the Apennines in Emilia. In this region, especially about Bologna, many of the richest archaeological finds of Etruscan remains have been made. There appears to be a sort of wedge of broad-headedness penetrating the peninsula nearly as far south as Rome. This could not be if the Etruscans had been ethnically of Greek or Semitic origin; for the Greeks were and are of a type quite similar to the Italians of the extreme south—of Mediterranean racial descent, in fact. Certainly no ethnic type of this kind has contributed largely to make up the modern Tuscan people.[10]

To us it appears as if here, in the case of the Etruscans as of the Teutonic immigrants, we find reason to suspect that the ethnic importance of the invasion has been immensely overrated by historians and philologists. It seems quite probable that the Etruscan culture and language may have been determined by the decided impetus of a compact conquering class; and that the peasantry or lower orders of population remained quite undisturbed. It is certain that the remains of the people unearthed in their tombs betray very mixed characteristics. Crania are very rare, owing to the customs of cremation which were in vogue; such as have been studied are of all types.[11] It appears, from the few that have been measured, that a long-headed (Greek?) element was rather predominant; and, as we have already observed, Lombroso and others are inclined to regard the peculiarly dolichocephalic people

Mixed Type. Island of Ischia. Cephalic Index, 83·6.

about Lucca as the last remnant of the pure Etruscan. If all Etruria were once like this, it must have changed wonderfully in the historic period, contrary to most of the experience we have related, for to-day this long-headed element is relatively quite scarce. For our own part, we regard the testimony of fifty thousand living peasants, more or less, as more credible than the evidence from a score or two of crania of uncertain origin, even though they be found in Etruscan tombs.

On the whole, we are inclined to the belief that our Etruscan ethnic origins must be sought in the north rather than in the south; in other words, that the Etruscans were an offshoot of our Alpine race of central Europe. Since the earliest times, as Zampa has proved, and it agrees with evidence from all around the Alps, there has been a steady outflow of population from this inhospitable habitat, unable as it is to afford sustenance to an increasing population. This downpour of broad-headed Alpine race types has entirely overcome the valley of the Po. In prehistoric times the people of Lombardy, Veneto, and Emilia were quite similar to the modern peasants in the extreme south. All Italy, in other words, was once Mediterranean in type. This has been proved. Is it not probable that the same flood of expanding population from the north which submerged these districts may have traversed the Apennines and overflowed both Etruria and Umbria? The so-called Etruscan historic invasion may have been merely an incident in this great demographic event. This internal origin for the Etruscan race is rendered all the more probable by other evidence close at hand. All the chief cities were well inland. None were on the coast, where Greek or Phœnician invaders by sea would most likely have located. The Etruscans, in fact, seem to have been quite ignorant of the art of navigation; and, finally, the testimony of place names points to the Alps as a point of initial dispersion, as Canon Taylor has shown.

Middle Italy south of Umbria has little of special interest to offer. It is merely intermediate between north and south. To make this transition clear, compare the portrait on preceding page with that of our pure Alpine type on page 725 and with the pure Mediterranean type on this page. Owing to the late Abyssinian war so many of the Calabrians and Sardinians in the south were in the field that it was impossible to procure photographs of these  Berber. Tunis.

Berber. Tunis.

Cephalic Index, 72. racial types. They are quite similar, however, in head form to those which prevail in Tunis. For all practical purposes this African will do as well. Notice that the breadth of forehead and the roundness of face in our medium type stand between the extremes on either side. In pigmentation and stature the same thing is true. Little by little as we go south the Alpine blonde is eliminated until we reach the Mediterranean race in all its purity.

The southern part of the Italian Peninsula is to-day the seat of a Mediterranean population of remarkably pure ethnic descent. The peasants are very long-headed, strongly brunette, and almost diminutive in stature. Especially is this true in the mountains of Calabria, where geographical isolation is at an extreme. Along the coasts we find little points of contact with invaders by sea. Apulia (see map of geography) especially contains many foreign colonies.[12] Some of these are of interest as coming from the extremely broadheaded country east of the Adriatic. So persistently have these Albanians kept by themselves that after four centuries they are still characterized by a cephalic index higher by four units than the pure long-headed Italians about them. Many Greek colonists have settled along these same coasts. They, however, being of the same ethnic Mediterranean stock as the natives, are not physically distinguishable from them.

In conclusion, let us for a moment compare the two islands of Sicily and Sardinia in respect of their populations. With the latter we may rightly class Corsica, although it belongs to France politically. Our maps corroborate the historical evidence with surprising clearness. In the first place, the fertility and general climate of Sicily are in marked contrast to the volcanic, often unpropitious geological formations of the other islands. In respect of topography as well, the differences between the two are very great. Sardinia is as rugged as the Corsican nubble north of it. In accessibility and strategic importance Sicily is alike remarkable. Commanding both straits at the waist of the Mediterranean, it has been, as Freeman in his masterly description puts it, "the meeting place of the nations." Tempting therefore and accessible, this island has been incessantly overrun by invaders from all over Europe—Sicani, Siculi, Fenicii, Greeks and Romans, followed by Albanians, Vandals, Goths, Saracens, Normans, and at last by the French and Spaniards. Is it any wonder that its people are less pure in physical type than the Sardinians or even the Calabrians on the mainland nearby? Especially is this noticeable on its southern coasts, always more open to colonization than on the northern edge. Nor is it surprising, as Freeman rightly adds, that "for the very reason that Sicily has found dwelling places for so many nations a Sicilian nation there never has been."

Sardinia and Corsica, on the other hand, are two of the most primitive and isolated spots on the European map, for they are islands a little off the main line. Feudal institutions of the middle ages still prevail to a large extent. We are told that the old wooden plow of the Romans is still in common use to-day.[13] This geographical isolation is peculiarly marked in the interior and all along the eastern coasts, where almost no harbors are to be found. Here in Sardinia stature descends to the very lowest level in all Europe, almost in the world. Whether a result of unfavorable environment or not, this trait is very widespread to-day. It seems to have become truly hereditary. It extends over fertile and barren tracts alike. In other details also there is the greatest uniformity all over the island—a uniformity at an extreme of human variation be it noted: for this population is entirely free from all intermixture with the Alpine race so prevalent in the north.

We have now seen how gradual is the transition from one half of Italy to the other. The surprising fact in it all is that there should be as much uniformity as our maps indicate. Despite all the overturns, the ups and downs of three thousand years of recorded history and an unknown age precedent to it, it is wonderful to observe how thoroughly all foreign ethnic elements have been melted down into the general population. The political unification of all Italy, the rapid extension of means of communication, and, above all, the growth of great city populations constantly recruited from the rural districts, will speedily blot out all remaining traces of local differences of origin. Not so with the profound contrasts between the extremes of north and south. These must ever stand as witness to differences of physical origin as wide apart as Asia is from Africa. This is a question which we defer to a subsequent article in our series, when we shall return specifically to trace the geographical origin of these great European elemental races each by itself.

- ↑ The best authority upon the living population is Dr. Ridolfo Livi, Capitano Medico in the Ministero della Guerra at Rome. To him I am personally indebted for invaluable assistance. His admirable Antropometria Militare, Rome, 1896, with its superb atlas, must long stand as a model for other investigators. Titles of his other scattered monographs will be found in the author's Bibliography of the Ethnology of Europe, shortly to appear in a Bulletin of the Boston Public Library. Among other references of especial value on Italy are: G. Nicolucci, Antropologia dell' Italia nel evo antico e nel moderno, in Atti del R. Accademia delle Scienze di Napoli, series 2 a, ii, 1888, No. 9, pp. 1-112; G. Sergi, Liguri e Celti nella valle del Po, in Archivio per I'Antropologia, xiii, 1883, pp. 117-175, gives a succinct account of the several strata of population; R. Zampa, Sull' etnografia storica ed antropologica dell' Italia, Atti del Accademia pontificia dei Nuovi Lincei, Rome, xliv, session May 17, 1891, pp. 173 seq.; and ibid., Crania Italica vetera, Memoric Accad. pont. dei Nuovi Lincei, vii, 1891, pp. 1-73. Full references to the other works of these authors, as well as of Calori, Lombroso, Helbig, Fligier, Virchow, et als., will be found in the authors bibliography above mentioned. Broca, in reviewing Nicolucci's work in Revue d'Anthropologie, 1874, gives a good summary of conclusions at that time, before the more recent methods of research were adopted.

- ↑ Exhaustive bibliography of each of these writers will be found in the Bulletin of the Boston Public Library, mentioned in the note on a preceding page.

- ↑ Whether this brachycephalic population is to be identified historically with the "Ligurians" or not is still matter of earnest dispute. Nicolucci, Calori, and most foreign authorities answer it affirmatively. On the other hand, such eminent specialists as Livi, Sergi, and Zampa agree in tracing the Ligurians back to a still more primitive and underlying stratum of population. This original stock was dolichocephalic, identical with the Mediterranean type in the south. Its direct descendants and survivors are the people of the modern province of Liguria, to be described shortly. These latter writers hold the broad headed more recent overlying people to be the true Celtic invaders from the Alps. Whichever theory be correct, we may rest assured of the ethnic facts in the case. There is no longer doubt of the two distinct strata. To christen them is a relatively unimportant matter, from our point of view.

- ↑ Vide, on the Umbrians, Zampa, in Archivio per l'Antropologia, xviii, 1888, pp. 175 et seq.; and Memorie Accademia pontiticia dei Nuovi Lincei, Rome, 1889, pp. Ill et seq.

- ↑ Les Gaulois d'ltalie, in Mem. pont. Accad. di Nuovi Lincei, Rome, viii, 1892, pp. 241-316.

- ↑ On the significance of the Alpine passes, vide Lentherie, Les Alpes devant l'Homme; also Jahresbericht des Vereins für Erdkunde zu Dresden, xviii.

- ↑ A good recent résumé of Etruscan culture is given by Lefevre in Revue Mensuelle de l'École d'Anthropologie, i, pp. 112 seq. and 268 seq., and also in Revue Linguistique.

- ↑ Von Czoernig, Helbig, Hoernes, Hochstetter (for a time), Koch, Müllenhoff, Niebuhr, Mommsen, Seemann, Steub, and Virchow. Taylor, in later work, seems to agree. Complete titles will be found in the author's Bibliography of the Ethnology of Europe above mentioned.

- ↑ The Italians range themselves on this side—viz., Brizio, Nicolucci, Lombroso, Sergi, and Zampa. With them stand Brinton, Evans, Lefevre, Montelius, and Myres, with Hochstetter in his later work.

- ↑ On the Greeks vide Zampa's Anthropologie Illyrienne, in Revue d'Anthropologie, series 3, i, pp. 632 seq., and Weisbach in Mitt. Anth. Ges. in Wien, xi, pp. 72 seq.

- ↑ The best references on this subject (see author's bibliography) are Zampa, 1891, pp. 48-56; Nicolucci, 1869, and especially 1888, pp. 12-52.

- ↑ Vide for details Zampa's excellent Vergleichende anthropologische Ethnographie von Apulien in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 1886, pp. 167-193, and 201-232.

- ↑ Bull. Soc. d'Anth., Paris, 1882, p. 310. On anthropology see work of Onnis, in Archivio per l'Antropologia, xxvi, 1890, pp. 27 seq., besides the other authorities aforenamed.