Popular Science Monthly/Volume 63/May 1903/The Opportunity of the Smaller Museums of Natural History

| THE OPPORTUNITY OF THE SMALLER MUSEUMS OF NATURAL HISTORY. |

By WILLIAM ORR,

SPRINGFIELD, MASS.

WITH the rapid growth of public libraries and the multiplication of books, periodicals and newspapers, there has arisen an urgent need for the direction of popular reading and for the promotion of serious study. Librarians are striving, with the aid of schools and teachers, to counteract the general tendency towards aimless superficial reading. Another educational agency that promotes exact knowledge, quickens observation and leads to research and consecutive study is the museum of natural history.

The near future may well see as great an interest in the establishment of museums as there is now in the founding of libraries. Such an institution can do an especially valuable service in the smaller city or town, provided its directors sense and seize their peculiar opportunity and clearly recognize the limitations imposed by local conditions. There should be no attempt to imitate the expensive buildings, exhaustive synoptic collections and the elaborate research and exploration of museums in the great centers of population. Salaries and incidental expenses can be kept at modest figures. Volunteer workers should be enlisted to cooperate with the paid officials. Public interest and the practical support of men of means are important factors to secure and retain. Connection with the public library under one general management makes for efficiency and economy.

For distinction and reputation the small museum must depend on special excellence in a few departments, on its representation of the local natural history and on its influence as an educational force in the community. Large sums may be spent to advantage on groups or on individual specimens when by such features local pride is aroused and visitors attracted. Carefully selected index collections can be used to give general views of the animal, plant and mineral worlds, while industry and ingenuity find full room for exercise in illustrating clearly and vividly the geology, botany and zoology of the region in which the museum is situated. As an agent of popular instruction the museum in the smaller centers possesses important advantages in the comparative ease with which people may be reached and interested. Usually the tone of life and the freedom from distracting influences are favorable

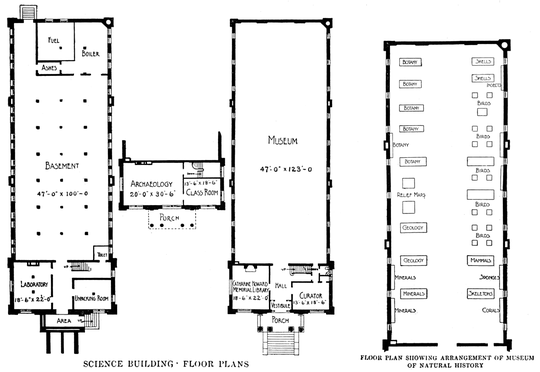

Science Building, containing Museum of Natural History and Catharine L. Howard Memorial Library of Science.

to earnest study. Adequate moral and financial support are assured by the promotion of a general interest in the museum. The open country is accessible for excursions by various scientific societies. Rambles are a delightful means of leading girls and boys to a knowledge of the treasures of nature in the hills and valleys near their homes. Even in the village, much may be done to relieve the monotony of life and to enrich the intellectual interest—so often mean and meager. As an active educational agency the museum should be in close and sympathetic touch with the public schools. Visits of teachers with groups of pupils should be encouraged. With people beyond school age, much may be done by lectures, classes and by scientific organizations. Attention should be directed not merely to the strictly scientific features of natural history, but also to the broader aspects and deeper meanings of nature, whence come sympathy, insight and refreshment of spirit.

As a setting for this work, the museum building should be simple in construction and planned with a view to economical management. Elaborate decoration or architectural effects are not desirable. Money can be expended to better advantage in other ways. Problems of lighting, construction and arrangement of cases, and the distribution of material call for careful attention. The general color effect and the background for objects are important elements in adding to the attractiveness of the collections. Cleanliness, neatness and abundant light are the cardinal virtues of the museum.

An illustration of the possibilities open to a small museum is afforded by the recent development of the Museum of Natural History, in Springfield, Massachusetts. This institution had its beginning in 1859, and was in a measure the result of interest aroused by a meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Science, held in Springfield that year. At the outset, the museum was placed under the control and care of the City Library Association, and this relation has been maintained ever since to the advantage of both institutions. For many 5'ears but little was done apart from the gathering of specimens, and dependence was in the main placed on contributions from local collectors. The result was a large amount of material, not always correctly classified, and decidedly miscellaneous in character. Better quarters were provided in 1871 in the new library building. and the museum was reorganized and brought into close relationship with the scientific department of the high school. In 1895, a commodious and suitable hall was provided for the collections in the Art Museum. The material was carefully classified and arranged for the first time on a systematic basis. With the new facilities, there came a notable increase in activity; public interest was enlisted and large gifts of specimens and money were made. Class-work, lectures and scientific societies were begun. In a few years the museum had outgrown its new quarters, and in 1898 it was provided with an attractive and commodious building for its own use.

The general plan and details of the building are made in accordance with the recognized needs of the institution, so that without any sacrifice of appearance, the care and supervision of the collections are reduced to lowest terms. The dimensions are: width, fifty feet; length, one hundred and fifty feet. In the front portion, which contains two stories, there are on the ground floor a library and the curator's office, and up-stairs a small class room and the department of archeology and ethnology. Beyond these apartments, and approached by a wide entrance hall, is the main exhibition room, forty-six feet wide and

twenty-two feet high. All the collections are on one floor and are lighted from overhead, a method that has proved most successful. Side windows are used chiefly for ventilation. By an abundant supply of electric lamps in the form of ceiling disks and wall brackets, the room can be brilliantly lighted in the evening. A series of radiators is placed under the side windows, so that there is no loss of wall or floor space. The floor is of selected maple, finished with an oil varnish. A simple and systematic arrangement of the collections is made possible by the size and shape of this room. Especial care has been taken to make the basement suitable for the storage of duplicate material for class and laboratory work. The floor is of Portland cement. At least six feet of the room is above the grade of the building, and there is generous window space so that the lighting is better than is found in many museum halls. In general the building is a modern French adaptation of Greek and Roman styles and is constructed of Pompeiian brick with trimmings of Indiana limestone and terra-cotta. The chief ornamental feature is the portico with massive limestone foundations and its four great columns of polished granite. The building is somewhat removed from the street so that the noise of traffic is escaped. It is situated near the center of the city and in close proximity to Library, Art Museum and High School. The opportunity thus afforded of cooperation between these institutions has been utilized with excellent results.

An important element in the success of the museum is the excellence of the cases. They have been designed so as to secure the largest possible glass surface and adequate protection against dust. The frames are of quartered oak and are fitted with the highest grade of plate-glass. In adjusting the shelves, the display of specimens to the best advantage has been constantly kept in mind, and the cases have been modified according to the kind of material exhibited. A buff color has proved most satisfactory for a background. On the main floor there are now ten standing cases, each ten feet long, four feet wide and seven feet high. This height seems most convenient for the utilization of all shelf space. There are thirteen wall cases of somewhat smaller dimensions than the standing floor cases. Four table cases are used for material in botany and two desk cases for shells and birds' eggs. For animal groups there are in all seventeen cases, making a total of forty cases in the main museum, to which must be added eight wall eases and two desk cases for the material in archeology, and historical relics. In the desk cases, only the upper part is used for display of specimens, and the space below is fitted with drawers for the preservation of duplicate and study collections.

The arrangement of the museum has been based on the principle of a simple and systematic grouping that should give an attractive appearance; where such a course seemed desirable, liberty has been taken to depart from a strictly formal classification. On the left side of the main hall are collections in mineralogy, lithology and geology. One alcove contains the Samuel Cotton Booth collection of local minerals, and a wall case is devoted to specimens of unusual rarity or beauty. This material is supplemented by relief maps, as, the Colorado cañon, the Volcanic District of the Auvergne in central France, the United States with a representation of the glacial ice-sheet, and southern New England. Photographs, wall maps and models complete the geological exhibit. In the basement there is a large amount of material for laboratory work and for illustration of local formations. In time, the latter will be placed in the main room and will constitute a fine presentation of the geology of Springfield and vicinity. Botany shares with geology the left side of the main hall. Under this division there is an extensive

herbarium of local flora, specimens of woods of North America and the Bahamas, that show tangential, cross and radial sections, and illustrations of the cocoanut palm, Indian corn and vegetable fibers.

Zoology, on the east side of the room, is represented by a very complete collection of local birds in the form of individual specimens and as groups in reproductions of the natural environment. There are fifteen of these groups, and they comprise the following species: song sparrow, American robin, spotted sandpiper, Indian bunting, Baltimore oriole, red-winged blackbird, wood-thrush, oven-bird, rose-breasted grosbeak, scarlet tanager, vireo, king-bird, bobolink and quail. The last group to be installed is an excellent representation of the prairie-hen. These realistic imitations of birds and insects amid their environment of foliage, blossoms and grasses constitute a feature of the museum that appeals with peculiar interest to children. Under the head of zoology there are good collections of corals and shells; the latter with over two thousand specimens, representing two hundred and twenty-nine genera and one hundred and seven species. Entomology is represented by twenty cases of butterflies with a total of two hundred and thirty-five specimens, twenty-two cases of moths with three hundred and twenty-three specimens and five boxes containing orthoptera, gall wasps and micro-lepidoptera with ninety-seven specimens, and three cases showing the life history of moths. There is also a study collection of one hundred and seventy-two noctuid moths. Some notable additions have been made to the department of mammals in the past few years. Mention should be made of an albinistic northern Virginia deer, an unusually rare specimen. A muskrat group, measuring five feet by seven feet, six inches, and showing the home of the animal in winter and summer with the environment carefully reproduced has been recently installed.

Last summer the museum received two remarkable gifts, a group of elk and one of buffalo. Each requires a case sixteen by sixteen feet on the floor and twelve feet high. The elk family of three members is placed among barberry bushes, quaking ash trees, moss-covered logs and stumps, in a veritable imitation of a woodland scene. Remarkable skill has been shown in the mounting of the animals, the arrangement of material and the modeling of the plant life, the leaves and blossoms. A bit of open prairie, with characteristic vegetation, constitutes the setting for the group of bison and is as effective in all respects as that of the elk. These additions are a means of attracting visitors and thus promote the popularity of the museum. As specimens of native animals, whose numbers are rapidly decreasing, their value will increase with years. The mounted mammals are supplemented by a series of skeletons of typical vertebrates. Attention is now being given to the better development of the department of mammals, especially in the direction of the local fauna.

In the upper story of the front portion of the museum building, there is on exhibition material in archeology, historical curios and ethnology. The Indian relics are of wide range in kind and geographical distribution, and the Connecticut Valley in which Springfield is situated is well represented. Out of a total of over three thousand specimens, seven hundred and sixty-six are from this valley and four hundred and forty-nine from Massachusetts and Connecticut beyond the limits of the valley. Professor Albertus T. Dakin, of the Peabody Museum, at Cambridge, has made this report on a part of the collection: "It constitutes a very interesting and valuable addition to any museum, but is of more than ordinary value to this community because of the fact, that with few exceptions, the entire collection of stone implements was gathered in the near vicinity of Springfield and all the specimens of stone art have been found within the confines of the Connecticut Valley. It is, moreover, one of the largest, if not the largest collection of distinctly local material that has been brought together and exhibited under one roof." Two important gifts, the Booth loan collection, and fifteen hundred carefully selected specimens given by

Dr. Philip Kilroy make up the largest part of the Indian relic collection. In the arrangement of the material a scheme has been followed that shows the geographical distribution, while at the same time the various implements have been grouped to illustrate the development of primitive art and industry and the uses of the different articles. Photographs, maps and descriptive labels furnish additional information in regard to the life of the Indian. Every facility is offered in the use of the collection for study and research. Under the auspices of the museum, a beginning has been made in the examination of old camp sites, quarries and fireholes in the vicinity, and some interesting results have been obtained already, with the promise of richer discoveries in the near future. A few cases devoted to historical relics and curios complete the material on exhibition in the museum.

The Catharine L. Howard Memorial Library, which is placed in a room at the left of the entrance hall, is a valuable aid in the work of the institution and is an efficient factor in encouraging study and research. It contains about six hundred standard reference volumes in the different branches of natural history. Geology is represented by the latest editions of Geikie, Dana, Lyell, Sedgwick, Le Conte, Lapparent and Credner, monographs on local geology, Dana's 'System of Mineralogy,' Williams' 'Crystallography' and Zittel's 'Paleontology.' Students of botany will find among other books the 'Natural History of Plants,' by Kerner and Oliver; Britton, Gray and Sargent. Zoologists will find Scudder on butterflies, 'Das Tierreich,' 'Cambridge Royal Natural History,' Woodward on the mollusca and authorities of like standing in all lines of the study of animal forms. The library is furnished after the fashion of a private room and provided with facilities for quiet reading. All books are accessible to readers, but none may be taken away.

By reason of the simplicity of the museum building, the excellence of the cases and careful installation of the collections at the outset, the work of administration has been conducted at very slight expense and with a small staff of attendants, and much time has been given to the active educational work of the museum. Constant effort is made to enlist volunteer assistants in the various lines of activity and to awaken popular interest in the different phases of natural history. The open hours are from two to six o'clock during the summer season and from one to five o'clock in the winter, but the collections are practically accessible at any hour of the day. Various devices are employed to make the room attractive and cheerful. The main hall is decorated by tropical plants, as palm, sago and century plants, in themselves an interesting study.

An especial effort has been made to bring the museum into close and helpful relations with the public schools. Out of duplicate material, collections illustrative of geology, mineralogy and lithology have been prepared and placed in various schools in the city and in near-by towns, where they have done good service in the branches of nature study undertaken by the teachers. Within the past year arrangements have been made with the school authorities whereby pupils arc brought to the museum in charge of instructors and in groups of such size that the greatest advantage may be gained. It is an interesting sight to see eager children gathered around a case or about a table of specimens, intent on the explanations and busy with pencil and note-book. While the scheme of museum visitation has not yet been thoroughly systematized, there is a steady growth in attendance, interest and results. During the year 1901-02, sixty-six classes, accompanied by teachers, visited the collections, with a total attendance of eight hundred and sixty-three. Apart from the class visits, teachers are making a practice of sending individual pupils to look up specimens and seek information at first hand. This plan has been followed more particularly in bird and plant study. Another means of rousing interest is through competition for prizes for the best collections or reports. Last year the supervisor of nature study offered a prize for the best collection in mineralogy, and the twenty-seven sets of specimens entered were exhibited in the museum and attracted much attention. This fall prizes were awarded for the best work done in collecting and studying beetles by any pupil below high school grade. In connection with this contest, two talks were given on 'Beetles and how to collect them,' and two excursions were conducted under the auspices of the museum. Ten children presented collections numbering in all 1,806 beetles. The prize winner had collected 202 species and 28 food plants. A number of rare specimens were among those presented, and the results showed that the young people had spent much time on the work with genuine interest and careful thought. There are many profitable lines on which such contests may be conducted.

Pupils from the high school are encouraged and guided to use the museum in connection with the study of zoology, botany, mineralogy and physiography. Teachers in the high school draw freely on the resources of the collection for specimens and are allowed under simple conditions to take out specimens for use in recitations and lectures.

Cooperation between schools and museums has been worked out in detail in many places in England, notably in Liverpool, Leeds and Manchester, and with excellent results. The director of the Liverpool Museum, Henry 0. Forbes, in a special circular dated July, 1902, reaches the following conclusion: 'That these efforts to interest children in nature study are producing good results is strikingly demonstrated by the way in which school children avail themselves of holidays to voluntarily visit our museum—the fact of a school holiday being of late always unmistakably indicated by the invasion of the museum by school children who evince a growing interest in the exhibits.'

Each year definite class-work is conducted in the Springfield Museum. During the past winter, twelve exercises on the chemical and physical properties of minerals with simple tests for determination were given by the assistant curator. A volunteer class in plant study was formed in the early spring and has continued to hold weekly meetings, with the exception of the two months of summer. Another means of arousing public interest has been found in the informal evening openings. During the season of 1901-02, six talks were given at these openings on such topics as 'Vegetable Fibers,' 'Industrial Insects, 'The History of a Lake,' and on 'Plants,' 'Buds' and 'Galls.' Special invitations were sent to people who do not generally visit the collection, and the results in attendance and interest were most gratifying. The daily attendance on the museum makes a total for the year of about 30,000, and this number steadily increases.

Several scientific societies find their home in the museum building. The botanical society has for many years held weekly meetings during the spring, summer and fall. The herbarium is in charge of the curator. The geological club uses the collections and reference books and as one result of its excursions specimens are added to the museum. By means of this club young people are given an interest in local geology and with this object in view the organization is making a careful study of the formations in and about Springfield, with excursions to interesting localities. The zoological club maintains a series of valuable meetings and has been fortunate in securing able lecturers from the many educational institutions in the near neighborhood. Meetings of all these societies are open to the public. There are now under consideration plans for the organization of holiday and vacation rambles whereby groups of children may be brought into sympathetic and intelligent relations with their surroundings and individually interested in particular phases of nature study. For mature minds regular lecture courses conducted on university extension methods are a possibility of the near future.

Another means of enlisting popular interest and promoting serious study has been found in special exhibits made from time to time. In the late winter, spring and early summer, the migrant birds that appear each month are displayed on the table and the specimens denoted by their scientific and popular names. Reliable reference books are near at hand. On the bulletin board a calendar is kept of the appearance of each species and a comparison made with the dates of previous years. These observations are printed in the annual report of the museum. The results for last spring, 1902, pointed to an unusually early arrival of many migrants. A similar arrangement is followed on the table devoted to botany, where one finds buds and blossoms as they appear. Early in the year the winter condition of certain plants is shown, and the progress in the development of leaf, buds and blossoms as they advance. On February 15, the chickweed, Stellaria lucidea, was found in bloom, and on the twenty-eighth, the skunk-cabbage, Symplocarpus. fætidus. The hood of the latter was cut so as to expose the spadix with its many flowers. Then followed in order, hepatica, bloodroot, marsh marigold, trailing arbutus and other spring flowers and tree blossoms. By the opening of June the exhibition had reached such an extent that another table was added. Twelve species of orchids were shown. One rare and beautiful flower, the Pentstemon grandiflorus, not supposed to exist east of the Mississippi, was found on the outskirts of the city. In all about four hundred separate plants were shown to the close of July. The exhibit was discontinued in July, but in September was opened again with various compositæ, as asters and golden rod, together with gentian and witch hazel, and as winter came on with cryptogams, as toadstools, lichens and mosses. Pupils in the high school have cooperated in the work by preparing lists to show the dates of the appearance of different blossoms. Corrected lists are published in the annual report and in time these will add materially to our knowledge of the flora of the region. There is also printed in the report a classified list of flowering plants and ferns growing on the museum grounds. Plans are under way for an exhaustive study and complete herbarium of the flora of Forest Park.

In planning lectures and exhibits, the museum officials are on the alert to take advantage of any special interest in the minds of people. Some years ago when there was much discussion of the value of mushrooms and the importance of care in collecting them, there were placed on special tables with careful descriptions many of the most common and important species. The exhibit of birds and plants appeal to an innate interest, easily aroused and maintained. Evidences are many that these various activities and influences of the museum are in a quiet but effective way developing in the community a spirit of sympathy, power of observation and a delight in the wonderful treasures of nature.

A city of the wealth and population of Springfield is certainly fortunate in the possession of a museum of natural history of such excellence and of collections so extensive and of such value for exhibition purposes and for study. These things have been made possible by the fine public spirit that characterizes the community. The City Library Association, including the Library, Art Museum and Museum of Natural History, constitutes a rallying point for the various interests in matters literary, artistic and scientific. Much of the efficiency and influence of the association is the result of the untiring and unselfish devotion and labors of the late Rev. Dr. William Rice, librarian from 1861 to 1897. Such is the confidence of the people in the work of the institution that the city makes each year a generous grant of money to meet the running expenses of the three departments of literature, art and science. In land, buildings, books and collections the total value of the property is nearly, if not over, $600,000, most of which has been the gift of public-spirited citizens. On account of the simplicity of the museum building and the excellent work done on the cases, and care taken in the installation of the collections, this department of the association is conducted at a minimum expense. The total annual appropriation to cover salaries, repairs, cleaning and lighting is $1,200, and this amount is rarely exceeded. Yet the museum is emphatically an active institution, and has never lacked zealous and enthusiastic workers. By an inevitable law of growth, as the museum is active and progressive, it constantly demands more room and greater facilities. Already in the short space of eight years it has twice outgrown its quarters. While the present building is commodious, the needs of the future were kept in mind in both construction and site, so that successive additions can be made until the building forms a quadrangle. When this extension is completed the main divisions of natural history, geology, botany and zoology will each have a floor space equal in extent to that of the present structure. With such a building Springfield's needs for museum facilities will be amply satisfied and the range of work and influence broadened.

And the field for the museum of natural history when conducted with enterprise and wisdom is one that well repays all effort and labor. Much of the best instruction in the public schools, training in observing and reflecting on the facts of nature is well adapted to assist the museum, while the latter institution, rightly used, widens the outlook. A growth in familiarity with the region surrounding the city makes possible profitable holiday rambles and vacation outings for the study of local natural history. There may be developed a love and appreciation of the delights that nature has in store for her students. Such pursuits are antidotes for the cares and perplexities that burden too many lives, so that a more healthful tone will pervade the social life of the community; nature opens her treasures to rich and poor alike, and the fullest indulgence in these joys carries no sorrow with it. In the larger centers well-equipped museums may well serve as training schools and points for the distribution of materials and examples of the best methods of administration. Their influence could be brought to bear on the smaller towns. Such a system with a very moderate expenditure of money would do much to relieve the barrenness and monotony which too often characterize the intellectual and social life of the country town.