Popular Science Monthly/Volume 85/October 1914/The Coniferous Forests of Eastern North America

| THE CONIFEROUS FORESTS OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA |

By Dr. ROLAND M. HARPER

COLLEGE POINT, N. Y.

IN eastern North America about thirty species of coniferous trees make up at least two thirds of the existing forest, while the remainder comprises something like 250 hardwood or broad-leaved species. About 70 per cent, of the lumber sawed in the eastern United States at the present time is of conifers or softwoods, and if the statistics for eastern Canada and for fuel, pulp-wood, cross-ties, poles, etc., were included the preponderance of softwood in the area under consideration would be still more evident. Most of the houses in the United States and Canada are built of coniferous wood, most of our paper comes from the same source, and, in all but the most densely populated regions, most of the domestic fuel.[1]

From the relative abundance and number of species it is evident that the average conifer species is represented by a much larger number of trees than the average hardwood. It happens that most of our conifers form pure stands of greater or less extent in some parts of their ranges at least, so that there are about as many types of coniferous forest as there are species of conifers. All but a few of the rarer or less important types will be described below, beginning with the northernmost, which are mainly confined to the glaciated region, and ending with those confined to the coastal plain, and one whose range extends southward into the tropics. The treatment of each type will include geographical distribution, correlations with soil, water, climate, fire,[2] etc., and notes on the economic aspects of the trees themselves and the regions in which they grow.

The Forest Types in Detail

The Boreal or Spruce Type.—The northernmost type of forest, which covers almost the whole of eastern North America from the arctic tundra down to latitude 45°, with many more or less isolated areas farther south, especially in the mountains, is mainly composed of jack pine (Pinus Banksiana), tamarack (Larix laricina), two or three species of spruce (Picea), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), and arbor-vitæ

Dense Growth of Spruce {Picea Mariana) and Arbor-vitæ (Thuja) in a Cold Swamp, Cheboygan Co., Michigan. August, 1912.

or northern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis). In places some one of these may cover considerable areas exclusively (this is especially true of the pine), but usually two or three of them are mixed together. They have much in common in general appearance, mature trees being as a rule spindle-shaped or narrowly conical in outline, with more or less deflexed branches, and leaves an inch or less in length. The tamarack is deciduous, and the rest evergreen.

Forests of similar aspect, and made up mostly of trees of the same genera, cover large areas in all the cooler parts of the northern hemisphere. Doubtless on account of the abundance of such trees in northern Europe, where most of our Anglo-Saxon traditions originated, the spindle-shaped tree has become firmly established as the conventional type of conifer. Illustrations of these trees in their native haunts abound in publications dealing with outdoor life in the extreme northern states and Canada printed since the invention of the half-tone process, about thirty years ago.

In the United States the jack pine prefers coarse sand and the other trees above mentioned are found mainly in peat bogs; but farther north they may grow in almost any kind of soil, wet or dry. (In Alaska even some of the glaciers are said to be partly covered with spruce forests.) The regions where they grow are characterized by cool and moderately humid climates, with an average temperature of 45° F. or less, and an average growing season (i. e., period free from killing frosts) of not

Burned Spruce Swamp, With Living Trees in Background, Cheboygan Co., Michigan. August, 1912.

more than 150 days. The ground freezes several feet deep in winter, and temperatures of -30° F. or lower are likely to be experienced by each tree many times during its life.

The average annual precipitation is 20 inches or more, and in most places in the boreal conifer region there is more of it in summer than in winter, which tends to keep the soil moist throughout the year.

A climatic factor which involves both temperature and precipitation is the amount of snowfall; and it appears from statistics of the snowfall of the United States recently published that the type of forest under consideration can be correlated pretty closely with an average annual snowfall of 50 inches and upward. Although it would not be exactly correct from a biological standpoint to say that the narrow conical form of these trees is an adaptation to heavy snows, like the steep roofs of Norway, for example, it would be difficult to imagine any other form of evergreen tree with the same amount of wood and foliage which would be less liable to injury from snow and ice than the spruces and balsams. The tamarack has an additional safeguard in that it loses its leaves in winter; and at the northern limit of the forests it is said to grow comparatively tall and straight while the spruces around it are much stunted.

Burned areas, in which all the trees have been killed by fires sweeping through their crowns, are and always have been, from all accounts, common throughout the spruce region (not only in the East, but also in the Rocky Mountains, where forests of different species but similar aspect predominate); and many great fires, involving loss of life and much property, have become historic.[3] In northern Michigan and doubtless in many other places where spindle-shaped conifers abound posters warning against the dangers of allowing fire to spread greet the traveler at every turn;[4] and some of the western railroads print similar advice in their time-tables.

Although at the present time the origin of most of the northern forest fires can be ascribed to human agencies, lightning is known to cause a considerable proportion of them (estimated by Plummer at 15 per cent.), and in prehistoric times it must have been the principal cause.[5] From all the evidence available it would seem that the normal frequency of fire at any one spot in the boreal conifer forests is about once in the average lifetime of a spruce tree, which may be between 50 and 75 years. The average extent of a single fire must be several square miles.

In the untold ages that fire has been a factor in the life-history of these forests there has developed a class of plants known as fireweeds, consisting of a score or more of herbs, shrubs, and short-lived deciduous trees, such as birch and aspen, which quickly take possession of burned areas and flourish until the dominant, but more slowly growing conifers have time to reestablish themselves. When the foliage of the conifers is consumed by fire the potash and other mineral nutrients stored up in several years' growth of evergreen leaves is returned to the soil in readily available form, and this must be a significant factor in the rapid growth of the fireweeds. Quite a lengthy chapter could be written about this phenomenon, which has almost no counterpart in the coniferous forests farther south, where fires are nearly always ground-fires, and do not kill the trees outright.

The economic aspects of these northern forests are numerous and varied. The soil and climate are not very favorable for agriculture, so that the farmer, the greatest enemy of forests in this country, has done little damage, and the timber is in no immediate danger of exhaustion. The trees are used to a considerable extent for lumber, and almost as much for pulp-wood; nearly all the large paper mills in North America being located not far from such forests. Logging is nearly all carried on in winter, when the snow facilitates hauling the logs to the nearest river or railroad. The Christmas trees used in northern cities are nearly all brought from the same region. The same forests furnish our spruce gum and Canada balsam, and among them are found the most important peat deposits in North America.[6]

The boreal conifer region is a favorite resort for hunters, trappers, fishermen, berry-pickers, campers, canoeists, hay-fever sufferers, etc., most of whom migrate northward in summer from the densely populated regions a little farther south. At certain times and places mosquitoes and black-flies make life in the north woods somewhat burdensome, but the mosquitoes are at least not of the malarial variety, and poisonous snakes and some other pests are conspicuous by their absence.

The White Pine (Pinus Strobus) ranges from Newfoundland and Manitoba to the mountains of Georgia, and associates with many other trees, mostly hardwoods, in various parts of its range; pure stands of it being the exception rather than the rule. It grows in almost any kind of soil except the richest and poorest, wettest and driest, but seems to prefer that containing a moderate amount of humus. From its distribution we may infer that it is confined to climates where the average temperature is less than 55° F., and the growing season not more than half the length of the year: climates pretty well suited for apples but not for cotton.[7]

This species is rather sensitive to fire, at least when young, and perhaps up to middle age. In northern lower Michigan and doubtless elsewhere there are large areas said to have been covered with white pine forests up to about thirty years ago, when the lumberman came along and felled them. Since then fires, mainly of human origin, have been too frequent to allow the pine to reproduce itself except in protected places like islands and shores of lakes and streams, and the uplands are covered with a worthless scrub of birch, aspen, bird cherry, and other fireweed trees, averaging about ten feet tall.

The white pine is one of the world's most important timber trees. It was originally so abundant, and its wood is so easily worked, that it has been used for almost every purpose that does not require great strength, hardness or durability. Millions of houses have been built of it, and probably hundreds of millions of dry-goods boxes. On account of its growing within easy reach of some of the oldest and most thickly settled parts of this country the value of its lumber which has been placed on the market in the last 300 years doubtless exceeds that of any other North American tree.[8] At the present time the leading states in the production of white pine lumber are Minnesota, Wisconsin, Maine, Michigan, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York and North Carolina, in the order named. But if the figures for the last census had been computed on a basis of equal areas, Massachusetts would rank first, New Hampshire second, and Minnesota third.

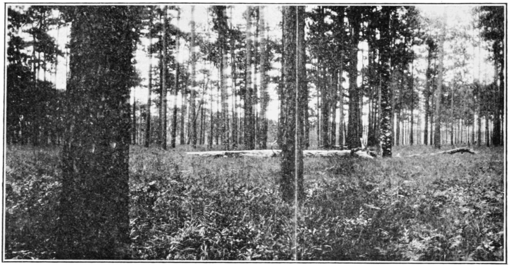

The Red or "Norway" Pine (Pinus resinosa) has a range approximately concentric with that of the white pine, but smaller. It is confined to the glaciated region, except that it has been reported from two or three counties in central Pennsylvania and one in West Virginia. In some places in the neighborhood of the upper Great Lakes it forms pure stands with little undergrowth,[9] something like the long-leaf pine forests of the south; but it is more commonly mixed with jack pine, white pine, or other trees. It grows in dry, usually sandy soil, nearly devoid of humus. Its climatic relations are perhaps sufficiently indicated by its distribution.

This species withstands fire almost as well as some of the southern pines to be discussed later, and it resembles them in general appearance, too. In mature trees the branches and foliage are too high up to be injured by ground fires, and the bark is thick enough to be reasonably fireproof. But even when the bark is burned through by a severe fire, making a large scar, the tree is not necessarily killed. At what age it becomes immune to brush fires has not been determined, but in the devastated pine lands of Michigan above mentioned there are many vigorous red pine saplings among the birches and aspens, as well as occasional tall trees of the same species which must have survived many fires.

The wood is so similar to that of the white pine that it is not usually distinguished in the lumber market or in the census returns. But reports on the wood-using industries of Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota, prepared in recent years by members of the U. S. Forest Service and published by the respective states, give the amount of each kind of wood used by manufacturers (i. e., that which passes beyond the stage of rough lumber, even if it is merely planed) in each state in a year, and distinguishes between lumber cut within the state and that

Young Trees of Red Pine (Pinus resinosa) in Brush Land Subject to Frequent Fires, Cheboygan Co. Michigan. August, 1912.

brought in from other states. From these we learn that the manufacturers of Michigan use in a year about 10 million feet of home-grown red pine, those of Wisconsin something over 6 million, and in Minnesota 167 million. (The corresponding figures for white pine are 70, 72 and 455; and both added together are less than half the total lumber production of the two species for these states as reported by the Tenth Census.)

The Hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis)[10] has a distribution very similar to that of the white pine, except that it is a little more southerly. It grows in several counties of Alabama, in which state the white pine is unknown. It commonly grows mixed with various hardwood trees and sometimes with white pine besides. It prefers moderately dry soils with considerable humus, perhaps more than any other eastern conifer. (The states which according to the last census cut more hemlock lumber than white pine—making due allowance for the inclusion of more than one species under the same name—have richer soils, on the whole, than those in which the reverse is true.)

This tree is confined to situations rarely or never visited by fire, being protected either by the scarcity of undergrowth, or by the topography, or both. It is probably very sensitive to fire, especially when young.

Formerly the hemlock was valued chiefly as a source of tanbark, and it was once, and still is in many places, as far apart as Michigan and Georgia, a common practise to cut the trees for their bark alone, and leave the logs to rot in the woods. At present it is used largely also for lumber and pulp-wood. The leading states in the production of hemlock lumber in 1909, in proportion to area, were Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Michigan, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maryland and Virginia, in the order named. (The first four of these, as well as Vermont, New York and Maryland, cut more hemlock than white pine.)

The Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida) ranges from New Brunswick and Ohio to the mountains of Georgia, but seems to form extensive pure

Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida) Near Lakehurst, N. J. Typical New Jersey pine-barrens. Trees in background killed by fire. August, 1909.

stands only in southeastern Massachusetts, eastern Long Island, and southern New Jersey. Such forests usually have a dense undergrowth of two shrubby oaks (Quercus ilicifolia and Q. prinoides), with poor sandy soils, and the ground-water level fairly constant throughout the year.

In its relations to fire the pitch pine seems to be intermediate between the spruces already mentioned and some of the southern pines. The pine-barrens of Long Island and New Jersey everywhere bear the marks of fire, which seems usually not to kill the older trees. Further studies of this point are needed.

This tree is usually too small, crooked or knotty to be of much value for lumber, but where it is abundant it has been used for many purposes, especially in the early days before transportation facilities enabled better woods to compete with it so-strongly. The soil in which it grows is of little value for ordinary agriculture, but in wet places among the pines, especially in Massachusetts and New Jersey, large crops of cranberries are gathered. The pine region of New Jersey formerly produced considerable quantities of bog iron ore[11] and glass sand. See The Popular Science Monthly, 42: 442, 830. 1893.

The Red Cedar (Juniperus Virginiana) grows nearly throughout

Red Cedar (Juniperus Virginiana) and Various Hardwood Trees, among Limestone Rocks on Mountain Slope Near Scottsboro, Alabama. March, 1913.

eastern North America between—but hardly overlapping—the boreal forests of high latitudes and altitudes and the tropical forests of southern Florida. It is most abundant on the northwestern flanks of the Alleghanies, in what might be called the interior hardwood region, and forms nearly pure stands, commonly called cedar glades, in Middle Tennessee and northern Alabama. (Of the numerous places named Lebanon in the United States it is altogether probable that those in Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama and Florida, if not most of the others, were named from the presence of cedar trees, although our cedar bears little resemblance to Cedrus Libani, the classical cedar of Lebanon.)

The soil in which this tree grows is usually dry, and nearly always thin or rocky, but it varies greatly in chemical composition. In Alabama, Tennessee and some other parts of the country the cedar is believed to prefer calcareous soils, but this does not seem to be true throughout its range, for it grows in many places where no lime can be detected without a careful chemical analysis.

This species is very sensitive to fire, and the places frequented by it, such as pastures, fence-rows, edges of marshes, dunes, rocks, bluffs, hammocks, etc., are all pretty well protected from fire in one way or another. In fact exemption from fire seems to be the only significant character that its diverse habitats have in common, from which we may conclude that that governs its local distribution more than anything else.[12]

The wood of the cedar is very durable, but now used mostly for pencils, in which this quality is not taken advantage of. Eepresentatives of the pencil-makers have scoured the country pretty thoroughly for it, and few large straight-grained trees have escaped them, even in small groves in the most out-of-the-way places in the South. Although it is not separated from some other species in the census returns, the cedar cut in 1909 in Tennessee (8,927,000 feet), Missouri (2,984,000 feet) and Alabama (2,869,000 feet) must be all or nearly all of this species.

The Southern White Cedar or "Juniper" {Chamœcyparis thyoides) is the only conifer that grows both in the glaciated region and in the coastal plain and nowhere else. It ranges from New Hampshire to Mississippi, but is not known more than 200 miles inland, or southeast of a straight line drawn from Charleston to Apalachicola (which excludes most of Florida); and there are several large gaps in its range. It usually grows in dense colonies of several hundred trees or more, much like the spruces farther north.

It is strictly a swamp tree, growing naturally only in permanently saturated soil, or peat. The water of these swamps is exceptionally free from mud, lime (perhaps also sulphur) and other mineral substances, but is usually colored dark brown by vegetable matter. Cities as far apart as Brooklyn, N. Y., and Mobile, Ala., get part of their water supply from streams in which Chamæcyparis grows; and the water of Dismal Swamp—one of the best-known localities for this species—used to be preferred for drinking purposes on ships sailing from Norfolk on long voyages. Tire manufacture of paper is an industry which seems to require good water in large quantities, and the only paper mills in the coastal plain known to the writer (viz., at Hartsville, S. C, and Moss Point, Miss.) have juniper growing in their immediate vicinity.

The relations of this species to fire have been little studied, but what evidence there is seems to indicate that they are much the same as in the case of the boreal forests already described.

The wood is very durable, and therefore used largely for poles, shingles, woodenware, etc., but it is not separated from that of arbor-vitæ and red cedar in the latest census returns.

The Scrub Pine (Pinus Virginiana), also known as Jersey pine, spruce pine, nigger pine, cliff pine, etc., bears considerable resemblance

Pinus Virginiana on Rocky Bluffs along Warrior River, Tuscaloosa Co., Alabama. March, 1911.

to the jack pine previously mentioned, but does not grow within 200 miles of it. It ranges from just south of the terminal moraine in New York and Indiana to central Alabama, nearly always forming dense groves or thickets with little admixture of other trees. It is common in the coastal plain of Virginia north of the James River, but farther south seems to be confined to the highlands. In Alabama its distribution is approximately coextensive with the coal region, where it is a familiar feature of the landscape. It grows in rather dry, poor, often rocky soil, but not quite the poorest. In Maryland and Virginia it is very common in abandoned fields, but toward its southern limits it prefers steep rocky bluffs.

This pine, like others with very short leaves, has a thin bark and is quite sensitive to fire, though a light ground fire does not necessarily injure mature trees. In young thickets fire sometimes sweeps through the tops of the trees and kills them outright, as in the boreal conifer forests first mentioned. Its local distribution seems to be governed largely by fire, as in the case of the red cedar, for the places where it grows are usually pretty well protected by their isolation, as in abandoned fields, by topography, as on bluffs, or by the sparseness of the undergrowth.

This tree does not often grow large enough to be useful for anything but fuel, charcoal and wood-pulp.[13]

The Southern Short-leaf Pines.—Two species (Pinus echinata and P. Tæda), which although they are easily distinguished have much in common, are called short-leaf pine in the South. The latter is distinguished in the literature of botany and forestry as "loblolly pine," a name which does not seem to be used much by lumbermen and other "natives."

Pinus echinata ranges from Staten Island and southern Missouri to northern Florida and eastern Texas, ascending the mountains of

Forest of Short-leaf Pine (Pinus echinata) a Few Miles Northeast of Tallahassee, Florida. April, 1914.

Georgia to an altitude of about 3,000 feet, while Pinus Tæda grows from Cape May to Arkansas, Texas and Central Florida, rarely more than 1,000 feet above sea-level. The former grows in dry soils somewhat below the average in fertility, while the latter prefers or tolerates a little more moisture and humus. Both are usually more or less mixed with oaks and hickories, or with each other, so that opportunities for getting satisfactory photographs of them are not very numerous.

The distribution of P. echinata corresponds approximately with mean temperatures of 55°-70°, and P. Tæda with about 60°-72°. The latter does not seem to be capable of enduring temperatures much below zero (Fahrenheit). It may be regarded more appropriately than any other as the typical tree of the South. Where it abounds cotton is the principal money crop, about half the population is colored, and a large majority of the white voters are Democrats. In South Florida, where it is unknown, there are no cotton fields, few negroes, few southern traditions, and many northern people; and substantially the same might be said of the southern Appalachian region, western Texas, and several other places just outside of the range of this tree.

Both species when mature have bark thick enough to withstand any ordinary forest fire, and the dead leaves in the woods in which they grow are likely to be burned nearly every year, with little apparent injury to the trees. Trees of either species less than ten years old probably suffer somewhat from fire, though.

Both are very abundant and important timber trees, not far inferior to the long-leaf pine mentioned below, and together they are now being cut at the rate of several billion feet annually. Probably even more trees have been cut by farmers than by lumbermen, for the soil in which they grow is adapted to many staple crops. They reproduce themselves very readily in abandoned fields, though, so that they are in no immediate danger of exhaustion.

The Black Pine[14] (Pinus serotina), which looks very much like P. Tæda, but is more closely related to P. rigida (whose range it overlaps very little if at all), is strictly confined to the sandier parts of the coastal plain, where the summers are wetter than the winters. It is frequent from southeastern Virginia to central Florida and southeastern Alabama, but not very abundant except in eastern North Carolina, where it is the dominant and characteristic tree of the "pocosins." Its favorite habitat is sour sandy or peaty swamps, where the water-level varies little throughout the year.

Its relations to fire have not been specially investigated. Its wood is similar to that of P. Tæda, from which it is not usually distinguished in the lumber markets.

The Cypress (Taxodium distichum) is one of our most interesting trees, from several points of view, and a great deal has been written about it. It ranges from Delaware and southwestern Indiana to Florida (within two degrees of the Tropic of Cancer) and Texas, and is almost

Cypress (Taxodium distichum) With Knees, in a Creek Swamp, Pickens Co., Alabama. Taken in early spring when trees were leafless. February, 1913.

confined to the coastal plain. It is usually abundant where it grows, but more or less associated with other deciduous trees.

This is a swamp tree, growing naturally only where the ground is alternately dry and overflowed. It can stand flooding to a depth of eight or ten feet for a few weeks at a time, and 25 feet for a few days, but does not seem to grow on the immediate banks of the Mississippi and other large rivers whose high-water periods last too long; except near their mouths where the seasonal fluctuations are necessarily less than they are farther up. Its occurrence on the banks of ox-bow lakes which were once part of the Mississippi River may therefore be used as evidence of the minimum age of such lakes.[15] It prefers soil that is rather rich, either from the amount of mineral plant food in the strata penetrated by its roots, or from alluvium deposited by streams.

The regions where this species grows have a mean temperature of about 53°-75°, a growing season of 180 to 360 days, and an average annual rainfall of 38 to 65 inches. It is successfully cultivated, however, not only in New York or even farther north of its natural range, but at the same time in ordinary dry soil of parks and streets.[16]

The cypress swamps are pretty well protected from fire most of the time by the wetness of the soil or the absence of inflammable material on the ground, but occasionally in a very dry season fire gets into the edge of such a swamp from the neighboring uplands and kills some of the trees, whose thin bark renders them rather sensitive.

The wood of our cypress, like that of the Old World tree of quite different appearance which bore the same English name long before ours was discovered by civilized man, is very durable and easily worked, and therefore cut in large quantities for shingles and other articles which are to be exposed to the weather or placed in contact with the soil. The last census reports 955,635,000 feet of cypress as having been sawed in 1909, nearly two thirds of this amount coming from Louisiana. Next in order were Florida, Arkansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, North Carolina, Missouri and Georgia. (Some of this amount, however, possibly 10 per cent., should be credited to the other species of cypress discussed a little farther on.) The soil in which cypress is found is usually too wet for cultivation and not easily drained, so that in spite of the tree's slow growth and the rapid rate at which it is being cut the supply will probably not be exhausted for many years.

The Long-leaf Pine (Pinus palustris), also known as yellow or Georgia pine, extends through the coastal plain from extreme southern Virginia to the vicinity of the Caloosahatchee River in Florida and the Trinity River in Texas, and also inland to the mountains of Georgia and Alabama, nearly 2,000 feet above sea-level. (It almost meets the white pine in Georgia.) In the greater part of its range it is the most abundant tree, and there are or have been many places where it is the only tree in sight. It probably was originally, and may be even yet, the most abundant tree in eastern North America. The long-leaf pine forests, or southern pine-barrens, differ from most others in their open park-like character. Even in a virgin forest of this kind one can usually see about a quarter of a mile in every direction; and the ground is carpeted with wire-grass or other coarse grasses, or with low shrubs.

This species grows best in poor soils, rather dry and sandy and devoid of humus, but never in the very poorest, such as sand dunes. The region covered by it has a warm-temperate climate, with very little

Park-like Virgin Forest of Long-leaf Pine (Pinus palustris), Colquitt Co., Georgia. August, 1903.

snow, and more rain in summer than in winter, except in northern Georgia and Alabama.

After reaching the age of four or five years the long-leaf pine seems to withstand fire better than any other tree known, with the possible exception of one or two of its near relatives to be discussed below; and what is more, it probably could not perpetuate itself very long without

Long-leaf Pine Forest with almost No Underbrush, in Southern Part of Liberty Co., Florida. June, 1909.

the aid of fire. All forests of it bear the marks of frequent ground fires, which in some places come nearly every year. At the present time, of course, most of the fires are of human origin, but those set by lightning in prehistoric times could spread over much larger areas than they do now, on account of the absence of clearings, roads, and other

Pure Stand of Black Pine (Finus serotina) in the Dover Pocosin, Jones Co., North Carolina. August, 1913.

artificial barriers, so that the frequency of fire at any one spot may not be much greater now than it was originally. A fire every year during the lifetime of the tree would be likely to prevent its reproduction, but in any area that escapes burning for a few years once in fifty years or so there is opportunity for a new crop of trees.

If fire were withheld too long the oaks and other hardwoods which grow in the long-leaf pine regions would take possession of the ground and gradually crowd the pine out, for its seedlings do not thrive in shade. Proofs of this can be seen in many places in the coastal plain, where fire is barred by the topography, as on bluffs bordering swamps, or by water, as on islands and narrow-necked peninsulas. Such places, in which the soil must have been originally much the same as in the neighboring pine forests, are nearly always occupied by what is known as "hammock" vegetation, consisting mostly of hardwood trees, which make a rather dense shade and cover the ground with humus.[17]

Few trees in the world are used by more people or in more different ways than the long-leaf pine. For strength and durability combined its wood has no superior among the pines, and it ranks equally high as a fuel. The same tree is our chief source of "naval stores" (i. e., turpentine and rosin).[18] In the regions where it abounds the log cabin of the small farmer and the mansion of the wealthy lumberman or naval stores operator are mostly built (from sills to shingles), painted, fenced and heated with the products of this tree. It supplies cross-ties, bridges, depots, cars and freight to many railroads, and motive power to some.[19] The masts, decks, and cargo of many a schooner on the Atlantic Ocean are of this species, and some of the busiest streets of our large cities have been paved with blocks of its wood in the last few years. Turpentine and lampblack from it are found in every drug-store.

As this pine grows mostly in comparatively level ground and almost unmixed with other trees, it has been cut as ruthlessly and wastefully as the northern white pine, and most of the once magnificent forests of it are now scenes of desolation. Although some other pines are mixed with it in the census returns, it is probably safe to say that at the present time the annual cut of it exceeds that of any other North American tree. Of the 2,736,756,000 feet of "yellow pine" cut in Louisiana and 1,100,840.000 feet cut in Florida in 1909 probably at least 75 per cent, was of this species.

The future prospects for it seem brighter than those of the white pine, for, as already pointed out, it is not affected much by fire, the greatest scourge of some of the northern forests. The long-leaf pine's worst enemy at present is the farmer, who in the last two or three decades has been taking possession of the once despised sandy pine lands very rapidly.[20] Notwithstanding the comparative poverty of the soil, the ease with which it can be cultivated and the mild climate are

powerful attractions; and where the soil is given over to agriculture the production of timber of course stops.[21]

The Pond Cypress (Taxodium imbricarium, or ascendens) is confined

Pond Cypress (Taxodium ascendens) in Very Shallow Flatwoods Pond (Dry at this Time), Pasco Co., Florida. April, 1909. This species is readily distinguished from T. distichum by its crooked trunk and coarser bark, among other things.

to the coastal plain, from eastern North Carolina (perhaps as far north as the Dismal Swamp) to southern Florida (south end of the Everglades) and eastern Louisiana. It extends over 150 miles inland in the Carolinas and Georgia, but apparently not over 100 miles in Alabama or 60 miles in Mississippi. It seems to be most abundant in Georgia, where it does not form large forests, but is often the dominant tree over several acres, especially in Okefinokee Swamp, where it seems to attain its maximum dimensions.[22]

It grows in poor soils, usually sand, inundated part of the year, but rarely if ever to a greater depth than five or six feet. (High-water mark is indicated by the height of the enlarged base of the trunk rather than by the knees, which are less characteristically developed in this species than in T. distichum.) Its favorite habitats are shallow ponds which dry up in spring, and the swamps of coffee-colored (i.e., not muddy) creeks and small rivers. The regions where it grows have an average temperature of 60°-75°, a growing season of 240 to 360 days, and an annual rainfall of 40 to 65 inches, over 40 per cent. of which falls in the four warmest months, June to September.

The pond cypress has a thicker bark than its better-known relative, and mature trees are practically immune to fire. The ponds in which it grows are likely to be swept in the dry season by fire, which chars the bark at the bases of the trees a little, but does no perceptible harm.

The wood is very similar to that of T. distichum (a little stronger and heavier, if anything), and not satisfactorily distinguished in the lumber trade, but the tree is usually too small, crooked or hollow to be worked up into lumber profitably. It is used principally for shingles, posts, poles, piles, cross-ties, etc. No statistics of its production are available, but it is evidently cut most extensively in Georgia and Florida.

The Southern Spruce Pine (Pinus glabra) is sometimes called white pine, or "bottom white pine," on account of its resemblance to the well-known northern tree, to which it is not very closely related, however. It ranges from southern South Carolina to central Florida and eastern Louisiana, in the coastal plain, and never forms pure stands, but associates with hardwood trees, especially the magnolia. It prefers soils well supplied with humus and protected from fire, like the white pine and hemlock, and is usually found in hammocks.

Its wood is softer than that of most other southern pines, and might be used as a substitute for white pine if it were more abundant and better known.

The Slash Pine (Pinus Elliottii) is also strictly confined to the coastal plain, ranging from southern South Carolina to southeastern Mississippi, inland about 165 miles in Georgia, and southward to about latitude 27° in Florida. It is sometimes the only tree on several acres, but is commonly associated with the pond cypress just mentioned, in shallow ponds or in swamps of small streams that are never muddy.[23]

Although it grows naturally only in saturated soil, it sometimes takes possession of comparatively dry ground from which long-leaf pine has been cut off; a circumstance which has led some uneducated people to believe that the long-leaf does not reproduce itself after lumbering, but mutates into another species. Some writers on forestry also have been misled into thinking that P. Elliottii is destined to take the place of P. palustris in the not distant future. But the range of the slash pine is much the smaller of the two, and it has shown no evidence of extending its boundaries since it was first recognized as a distinct species, about 35 years ago.

It is not injured perceptibly by fire, except when very young. Its economic properties are practically the same as those of the long-leaf pine, from which it is seldom distinguished in the lumber and naval stores markets. Its distribution corresponds approximately with that of the sea-island cotton crop, except that this cotton is not now raised west of the Chattahoochee River, while the pine extends nearly to the Pearl River.

The Florida Spruce Pine (Pinus clausa), a near relative of P. Virginiana, is the least widely distributed of all the eastern conifers, being

Interior of a Florida Spruce Pine (Pinus clausa) Forest on a Peninsula of Lake Tsala Apopka, Citrus Co., Florida; taken from a point about twenty feet from the ground. March, 1914. The abundance of "Spanish moss" (Tillandsia usneoides) indicates the infrequency of fire.

almost confined to one state. It ranges from Baldwin County on the coast of Alabama to Dade County, Florida, about latitude 26°. Like the somewhat similar jack pine of the north, it is confined to the most sterile soils imaginable, where other pines are scarce or absent. Its favorite soil, about 99 per cent, white sand, is most extensively developed in the lake region of peninsular Florida, where it supports a peculiar type of vegetation known as "scrub" consisting mostly of this pine, two small evergreen oaks (Quercus geminata and Q. myrtifolia), saw-palmetto and several other evergreen shrubs, with very little herbaceous growth: grasses and leguminous plants especially being conspicuous by their

absence. Outside of the lake region this type of soil and vegetation is principally confined to old stationary dunes near the coasts.

Fire sweeps through the scrub on the average about once in the lifetime of the trees, as in the boreal conifer forests, and kills the pines completely; but their cones, which normally remain closed for years, then open and discharge seeds for a new crop.

The wood of this pine is of little value, and the soil in which it grows is worthless for ordinary crops. But on the east coast of Florida south of latitude 28°, where frost is sufficiently rare to make such

Pinus Caribaea on Top of a Limestone Cliff Near Cocoanut Grove, Dade Co., Florida. March, 1909.

ventures profitable, large areas of old dunes have been cleared of their spruce pines and planted in pineapples. The pineapple is peculiar in belonging to a family of air-plants (Bromeliaceæ), and taking very little nourishment from the soil.

Our southernmost conifer, Pinus Caribæa, seems to have no distinctive common name in general use. (It has been called "Cuban pine" by several writers on forestry in recent years, but that name would be more appropriate for Pinus Cubensis, a species confined to eastern Cuba.) It is abundant in South Florida, and may extend along the coast to Georgia and Mississippi, though this point has not yet been determined beyond question. It is said to occur also in the Bahamas, western Cuba, the Isle of Pines, and British Honduras. It grows in pure stands, like the long-leaf, and south of the Caloosahatchee River it is almost the only pine, and more abundant than all other trees combined. It is confined to low regions within 100 feet of sea-level, and the saw-palmetto is usually the most conspicuous feature of the undergrowth (in Florida, but not in the tropics, for this palmetto does not grow farther south).

It grows mostly in sandy soil north of Miami, and on limestone rock south of there, where sand is scarce. Although it occupies the driest soils within its range (quite unlike its near relative P. Elliottii), the country where it grows is so low that there is usually water within two or three feet of the surface. The climate is subtropical, with no snow and little frost, and the summers are much wetter than the winters.

This species withstands fire about as well as P. palustris and P. Elliottii do, or perhaps even better, and is exposed to it as often.

Its wood is similar to that of the long-leaf pine, except that it is more resinous and brittle, and therefore is not used much for lumber except locally where there is no other pine within easy reach. The gum does not flow readily, and consequently very little turpentine is obtained from this species; but it is not unlikely that the increasing scarcity of long-leaf pine may before long bring about the invention of some method for utilizing P. Caribæa as a profitable source of naval stores. The range of this species lies almost entirely south of the cotton crop, but the soil or rock in which it grows is being planted extensively to grape-fruit, mangoes, avocadoes, and other tropical fruits.

- ↑ A map between pages 488 and 489 of the 9th volume of the Tenth Census shows the distribution of coal and wood fuel in the United States three decades ago.

- ↑ Forest fires have generally been looked upon as regrettable accidents, and much more thought has been given to devising means to prevent them than to studying their geographical distribution and historical frequency. But those that start from natural causes seem to be just as much a part of Nature 's program as rain, snow and wind (which like fire may do both good and harm at the same time), and to be subject to more or less definite laws. Their frequency, extent and effects vary greatly in different parts of the country and in different types of forests, as will be shown below, and nearly every species of conifer seems to have become accustomed or adjusted to a certain amount of fire, as to other environmental factors.

- ↑ See Pinchot's "Primer of Forestry" (U.S. Forestry Bulletin 24), Part 1, pp. 79-83, 1897; also U. S. Forestry Bulletin 117, by F. G. Plummer, 1912, especially map on page 22.

- ↑ Several such posters are reproduced in colors in American Forestry for November, 1913.

- ↑ See papers by Dr. Robert Bell in Forest Leaves for October, 1889, and the Scottish Geographical Magazine for June, 1897, and Bulletins 111 and 117 of the U. S. Forest Service, by F. G. Plummer, 1912. The second of Dr. Bell's papers, which is on the forests of Canada, contains much valuable information on other subjects than fire.

- ↑ Bulletin 16 of the U. S. Bureau of Mines, by Dr. Charles A. Davis, 1911, contains a large colored map showing the distribution of peat in the United States. The Canadian deposits are still more extensive.

- ↑ The range of the white pine perhaps does not overlap that of the cotton crop at all, though they can be seen within a mile of each other at the western base of the Blue Ridge in northern Georgia.

- ↑ For valuable notes on the economic history of this and other pines see Bulletin 99 of the U. S. Forest Service, by Hall and Maxwell, 1911.

- ↑ There are two illustrations of such forests in Minnesota in The Popular Science Monthly for November, 1912 (p. 535), and another on page 10 of a report on the Wood-using industries of Minnesota published by the State Forestry Board in 1913.

- ↑ Also called "spruce pine" in Georgia and Alabama, if not farther north. The settlement of Spruce Pine, Ala., takes its name from this tree (see Bull. Torrey Bot. Club, 33: 524. 1906), and the same may be true of the place similarly named in North Carolina and even of Spruce, Ga.

- ↑ There is an interesting sketch of the old iron industry in southern New Jersey by Gifford in The Popular Science Monthly for April, 1893.

- ↑ This was discussed at some length in Torreya, 12: 145-154, July, 1912. The most complete treatise on red cedar is Bulletin 31 of the Division of Forestry of the U. S. Department of Agriculture, by Dr. Charles Mohr, 1901.

- ↑ The most complete account of it available is Bulletin 94 of the U. S. Forest Service, by W. D. Sterrett, 1911.

- ↑ This is the name by which it goes in Georgia. In the books it is designated as "pond pine," a rather inappropriate and perhaps wholly arbitrary name.

- ↑ See Science, II., 36: 760-761, November 29, 1912.

- ↑ In such situations its characteristic "knees," the tops of which in a state of nature seem to indicate the greatest height of water to which the tree is accustomed, are developed on a very small scale if at all.

- ↑ The idea that fire is essential to the long-leaf pine has been expressed long ago by a few other observers in the south, but has never been generally accepted by writers on forestry, most of whom live in regions where the normal frequency of forest fires is much less. For more extended discussions of the problem see Bull. Torrey Bot. Club, 38: 515-525, 1911; Geol. Surv. Ala. Monog., 8: 25-27, 83, June, 1913; Literary Digest, 47: 208, August 9, 1913; American Forestry, 19: 667-669, October, 1913.

- ↑ The old method of extracting turpentine has been described in The Popular Science Monthly for April, 1887, and February, 1896; and the modern cup-and-gutter method by Dr. C. H. Herty, the inventor thereof, in Bulletin 40 of the IJ. S. Bureau of Forestry, 1903.

- ↑ A generation ago pine wood seems to have been the prevailing fuel for locomotives in the coastal plain, but most of the railroads have had to abandon it on account of its growing scarcity.

- ↑ The "wire-grass country" of Georgia, an area of about 10,000 square miles near the center of the range of this tree, increased in population about 60 per cent, between 1890 and 1900, and 35 per cent, between 1900 and 1910, which necessitated the creation of ten new counties in that part of the state since 1904. Somewhat similar developments have been taking place in the corresponding parts of Florida, Alabama and Mississippi at the same time.

- ↑ For valuable information about the economic aspects of the long-leaf and several other southeastern pines see Bulletin 13 of the Division of Forestry, U. S. Department of Agriculture, by Dr. Charles Mohr (1896 and 1897).

- ↑ See Science, II., 17: 508, March 27, 1903; Bull. Torrey Bot. Club, 32: 113, 1905; The Popular Science Monthly, 74: 603, 604, 607, 612, June, 1909; The Auk, 30: 485-487, October, 1913.

- ↑ There is an illustration of a forest of this species in the The Popular Science Monthly for June, 1909, p. 607.