Researches into the Early History of Mankind and the Development of Civilization/Chapter 5

CHAPTER V.

PICTURE-WRITING AND WORD-WRITING.

The art of recording events, and sending messages, by means of pictures representing the things or actions in question, is called Picture-Writing.

The deaf-and-dumb man's remark, that the gesture-language is a picture-language, finds its counterpart in an observation of Wilhelm von Humboldt's, that "In fact, gesture, destitute of sound, is a species of writing." There is indeed a very close relation between these two ways of expressing and communicating thought. Gesture can set forth thought with far greater speed and fulness than picture-writing, but it is inferior to it in having to place the different elements of a sentence in succession, in single file, so to speak; while by a picture the whole of an event may be set in view at one glance, and that permanently, so as to serve as a message to a distant place or a record to a future time. But the imitation of visible qualities as a means of expressing ideas is common to both methods, and both belong to similar conditions of the human mind. Both are found in very distant countries and times, and spring up naturally under favourable circumstances, provided that a higher means of supplying the same wants has not already occupied the place which they can only fill very partially and rudely.

There being so great a likeness between the conditions which cause the use of the gesture-language and of picture-writing, it is not surprising to find the natives of North America as proficients in the one as in the other. Their pictures, as drawn and interpreted by Schoolcraft and other writers, give the best information that is to be had of the lower development of the art[1]

Fig. 2. Fig. 2 is an Indian record on a blazed pine-tree (to blaze a tree is to wound (blesser) its side with an axe, so as to mark it with a conspicuous white patch). On the right are two canoes (2 and 4), with a catfish (1) in one of them, and a fabulous animal, known as the copper-tailed bear (3), in the other. On the left are a bear and six catfish; and the sense of the picture is simply that two hunters, whose names, or rather totems or clan-names, were "Copper-tailed Bear" and "Catfish," went out on a hunting expedition in their canoes, and took a bear and six cat-fish.

Fig. 3 is a picture on the face of a rock on the shore of Lake Superior, and records an expedition across the lake, which was led by Myeengun, or "Wolf," a celebrated Indian chief. The canoes with the upright strokes in them represent the force of the party in men and boats, and Wolf's chief ally, Kishkemunasee, that is, "Kingfisher," goes in the first canoe. The arch with three circles below it shows that there were three suns

under heaven, that is, that the voyage took three days. The tortoise seems to indicate their getting to land, while the representation of the chief himself on horseback shows that the expedition took place since the time when horses were introduced into Canada.

Fig. 4.

The Indian grave-posts, Fig. 4, tell their story in the same child-like manner. Upon one is a tortoise, the dead warrior's totem, and a figure beside it representing a headless man, which shows he is dead. Below are his three marks of honour. On the other post there is no separate sign for death, but the chief's totem, a crane, is reversed. Six marks of honour are awarded to him on the right, and three on the left. The latter represent three important general treaties of peace which he had attended; the former would seem to stand for six war-parties or battles. The pipe and hatchet are symbols of influence in peace and war.

The great defect of this kind of record is that it can only be understood within a very limited circle. It does not tell the story at length, as is done in explaining it in words; but merely suggests some event, of which it only gives such details as are required to enable a practised observer to construct a complete picture. It may be compared in this respect to the elliptical forms of expression which are current in all societies whose attention is given specially to some narrow subject of interest, and where, as all men's minds have the same frame-work set up in them, it is not necessary to go into an elaborate description of the whole state of things; but one or two details are enough to enable the hearer to understand the whole. Such expressions as "new white at 48," "best selected at 92," though perfectly understood in the commercial circles where they are current, are as unintelligible to any one who is not familiar with the course of events in those circles, as an Indian record of a war-party would be to an ordinary Londoner.

Though, however, familiarity with the picture-writing of the Indians, as well as with their habits and peculiarities, might enable the student to make a pretty good guess at the meaning of such documents as the above, which are meant to be understood by strangers, there is another class of picture-writings, used principally by the magicians or medicine-men, which cannot be even thus interpreted. The songs and charms used among the Indians of North America are repeated or sung by memory, but, as an assistance to the singer, pictures are painted upon sticks, or pieces of birch-bark or other material, which serve to suggest to the mind the successive verses.

Fig. 5.Some of these documents, with the songs to which they refer, are given in Schoolcraft, and one or two examples will show sufficiently how they are used, and make it evident that they can only convey their full meaning to those who know by heart already the compositions they refer to. They are mere Samson's riddles, only to be guessed by those who have ploughed with his heifer. Thus, a drawing of a man with two marks on his breast and four on his legs (Fig. 5) is to remind the singer that at this place comes the following verse:—

"Two days must you sit fast, my friend,—

Four days must you sit still."

Fig. 6 is the record of a love-song—(1) represents the lover; in (2) he is singing, and beating a magic drum; in (3) he surrounds himself with a secret lodge, denoting the effects of his necromancy; in (4) he and his mistress are shown joined by a single arm, to indicate the union of their affections, in (5) she is shown on an island; in (6) she is asleep, and his voice is shown, while his magical powers are reaching her heart; and the heart itself is shown in (7). To each of these figures a verse of the song corresponds.

1. It is my painting that makes me a god.

2. Hear the sounds of my voice, of my song; it is my voice.

3. I cover myself in sitting down by her.

4. I can make her blush, because I hear all she says of me.

5. Were she on a distant island, I could make her swim over.

6. Though she were far off, even on the other hemisphere.

7. I speak to your heart.

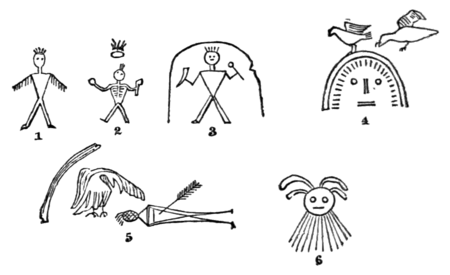

Fig. 7 is a war-song. The warrior is shown in (1); he is drawn with wings, to show that he is active and swift of foot. In (2) he stands under the morning star; in (3) he is standing under the centre of heaven, with his war-club and rattle; in (4) the eagles of carnage are flying round the sky; in (5) he lies slain on the field of battle; and in (6) he appears as a spirit in the sky. The words are these:—

1. I wish to have the body of the swiftest bird.

2. Every day I look at you; the half of the day I sing my song.

3. I throw away my body.

4. The birds take a flight in the air.

5. Full happy am I to be numbered with the slain.

6. The spirits on high repeat my name.

Catlin tells how the chief of the Kickapoos, a man of great ability, generally known as the "Shawnee Prophet," having, as was said, learnt the doctrines of Christianity from a missionary, taught them to his tribe, pretending to have received a super- natural mission. He composed a prayer, which he wrote down on a flat stick, "in characters somewhat resembling Chinese letters." When Catlin visited the tribe, every man, woman, and child used to repeat this prayer morning and evening, placing the fore-finger under the first character, repeating a sentence or two, and so going on to the next, till the prayer, which took some ten minutes to repeat, was finished.[2] I do not know whether any of these curious prayer-sticks are now to be seen, but they were probably made on the same principle as the suggestive pictures used for the native Indian songs.

Picture-writing is found among savage races in all quarters of the globe, and, so far as we can judge, its principle is the same everywhere. The pictures on the Lapland magic drums, of which we have interpretations, serve much the same purpose as the American writing. Savage paintings, or scratchings, or carvings on rocks, have a family likeness, whether we find them in North or South America, in Siberia or Australia. The interpretation of rock-pictures, which mostly consist of few figures, is in general a hopeless task, unless a key is to be had. Many are, no doubt, mere pictorial utterances, drawings of animals and things without any historical sense; some are names, as the totems carved by those who sprang upon the dangerous leaping-rock at the Red Pipestone Quarry.[3] Dupaix noticed in Mexico a sculptured eagle, apparently on the boundary of Quauhnahuac, "the place near the eagle," now called Cuernavaca,[4] and the fact suggests that rock-sculptures may often be, like this, symbolic boundary marks. But there is seldom a key to be had to the reading of rock-sculptures, which the natives generally say were done by the people long ago. I have seen them in Mexico on cliffs where one can hardly imagine how the savage sculptors can have climbed. When Humboldt asked the Indians of the Oronoko who it was that sculptured the figures of animals and symbolic signs high up on the face of the crags along the river, they answered with a smile, as relating a fact of which only a stranger, a white man, could possibly be ignorant, "that at the time of the great waters their fathers went up to that height in their canoes."[5]

As the gesture-language is substantially the same among savage tribes all over the world, and also among children who cannot speak, so the picture-writings of savages are not only similar to one another, but are like what children make untaught even in civilized countries. Like the universal language of gestures, the art of picture-writing tends to prove that the mind of the uncultured man works in much the same way at all times and everywhere. As an example of the way in which it is possible for an observer who has never realised this fact to be led astray by such a general resemblance, the celebrated "Livre des Sauvages" may be adduced.

This book of pictures had been lying for many years in a Paris library, before the Abbé Domenech unearthed it and published it in facsimile, as a native American document of high ethnological value. It contains a number of rude drawings done in black lead and red chalk, in great part enormously in- decent, though perhaps not so much with the grossness of the savage as of the European blackguard. Many of the drawings represent Scripture scenes, and ceremonies of the Roman Catholic church, often accompanied by explanatory German words in the cursive hand, one or two of which, as the name "Maria" written close to the rude figure of the Virgin Mary, the Abbé succeeded in reading, though most of them were a deep mystery to him. There are an evident Adam and Eve in the garden, with "betruger" (deceiver) written against them; Adam and Eve sent out of Paradise, with the description "gebant" (banished); a priest offering mass; figures with the well-known rings of bread in their hands, explained as "fassdag" (fast-day), and so on. There is no evidence of any connexion with America in the whole matter, except that the document is said to have come into the hands of a collector, in company with an Iroquois dictionary, and that the editor says it is written on Canadian paper, but he gives no reason for thinking so. So far as one can judge from the published copy, it may have been done by a German boy in his own country. One of the drawings shows a man with what seems a mitre on his head, speaking to three figures standing reverently before him. This personage is entitled "grosshud" (great-hat), a common term among the German Jews, who speak of their rabbis, in all reverence, as the "great hats."

The Abbé Domenech had spent many years in America, and was, no doubt, well acquainted with Indian pictures. Moreover, the resemblance which struck him as existing between the pictures he had been used to see among the Indians, and those in the "Book of the Savages," is quite a real one. A great part of the pictures, if painted on birch-bark or deer-skins, might pass as Indian work. The mistake he made was that his generalization was too narrow, and that he founded his argument on a likeness which was only caused by the similarity of the early development of the human mind.

Map-making is a branch of picture-writing with which the savage is quite familiar, and he is often more skilful in it than the generality of civilized men. In Tahiti, for instance, the natives were able to make maps for the guidance of foreign visitors.[6] Maps made with raised lines are mentioned as in use in Peru before the Conquest,[7] and there is no doubt about the skill of the North American Indians and Esquimaux in the art, as may be seen by a number of passages in Schoolcraft and elsewhere.[8] The oldest map known to be in existence is the map of the Ethiopian gold-mines, dating from the time of Sethos I., the father of Rameses II.,[9] long enough before the time of the bronze tablet of Aristagoras, on which was inscribed the circuit of the whole earth, and all the sea and all rivers.[10]

The highest development of the art of picture-writing is to be found among the ancient Mexicans. Their productions of this kind are far better known than those of the Red Indians, and are indeed much more artistic, as well as being more systematic and copious. Some of the most characteristic specimens have been drawn and described by Alexander von Humboldt, and Lord Kingsborough's great work contains a huge mass of them, which he published in facsimile in support of his views upon that philosopher's stone of ethnologists, the Lost Tribes of Israel.

The bulk of the Mexican paintings are mere pictures, directly representing migrations, wars, sacrifices, deities, arts, tributes, and such matters, in a way not differing in principle from that of the lowest savages. But in the historical records and calendars, the events are accompanied by a regular notation of years, and sometimes of divisions of years, which entitles them to be considered as regularly dated history. The art of dating events was indeed not unknown to the Northern Indians. A resident among the Kristinaux (generally called for shortness, Crees), who knew them before they were in their present half-civilized state, says that they had names for the moons which make up the year, calling them "whirlwind moon," "moon when the fowls go to the south," "moon when the leaves fall off from the trees," and so on. When a hunter left a record of his chase pictured on a piece of birch-bark, for the information of others who might pass that way, he would draw a picture which showed the name of the month, and make beside it a drawing of the shape of the moon at the time, so accurately, that an Indian could tell within twelve or twenty-four hours the month and the day of the month, when the record was set up.[11]

It is even related of the Indians of Virginia, that they recorded time by certain hieroglyphic wheels, which they called "Sagkokok Quiacosough," or "record of the gods." These wheels had sixty spokes, each for a year, as if to mark the ordinary age of man, and they were painted on skins kept by the principal priests in the temples. They marked on each spoke or division a hieroglyphic figure, to show the memorable events of the year. John Lederer saw one in a village called Pommacomek, on which the year of the first arrival of the Europeans was marked by a swan spouting fire and smoke from its mouth. The white plumage of the bird and its living on the water indicated the white faces of the Europeans and their coming by sea, while the fire and smoke coming from its mouth meant their firearms.[12] Thus the ancient Mexicans (as well as the civilized nations of Central America, who used a similar system) can only claim to have dated their records more generally and systematically than the ruder North American tribes.

The usual way of recording series of years among the Mexicans has been often described. It consists in the use of four symbols—tochtli, acatl, tecpatl, calli, i.e. rabbit, cane, cutting- stone, house, each symbol being numbered by dots from 1 to 13, making thus 52 distinct signs. Each year of a cycle of 52 has thus a distinct numbered symbol belonging to it alone, the numbering of course not going beyond 13. These numbered symbols are, however, not arranged in their reasonable order, but the signs change at the same time as the numbers, till all the 52 combinations are exhausted, the order being 1 rabbit, 2 cane, 3 knife, 4 house, 5 rabbit, 6 cane, and so on. I have pointed out elsewhere the singular coincidence of a Mexican cycle with an ordinary French or English pack of playing-cards, which, arranged on this plan, as for instance ace of hearts, 2 of spades, 3 of diamonds, 4 of clubs, 5 of hearts again, and so on, forms an exact counterpart of an Aztec cycle of 52 years. The account of days was kept by series combined in a similar way, but in different numbers.[13]

The extraordinary analogy between the Mexican system of reckoning years in cycles, and that still in use over a great part of Asia, forms the strongest point of Humboldt's argument for the connexion of the Mexicans with Eastern Asia, and the remarkable character of the coincidence is greatly enforced by the fact, that this complex arrangement answers no useful purpose whatever, inasmuch as mere counting by numbers, or by signs numbered in regular succession, would have been a far better arrangement. It may perhaps have been introduced for some astrological purpose.

The historical picture-writings of the Mexicans seem for the most part very bare and dull to us, who know and care so little about their history. They consist of records of wars, famines, migrations, sacrifices, and so forth, names of persons and places being indicated by symbolic pictures attached to them, as King Itzcoatl, or "knife-snake," by a serpent with stone knives on its back; Tzompanco, or "the place of a skull," now Zumpango, by a picture of a skull skewered on a bar between two upright posts, as enemies' skulls used to be set up; Chapultepec, or "grasshopper hill," by a hill and a grasshopper, and so on, or by more properly phonetic characters, such as will be presently described. The positions of footprints, arrows, etc., serve as guides to the direction of marches and attacks, in very much the same way as may be seen in Catlin's drawing of the pictured robe of Ma-to-toh-pa, or "Four Bears." The mystical paintings which relate to religion and astrology are seldom capable of any independent interpretation, for the same reasons which make it impossible to read the pictured records of songs and charms used further north, namely, that they do not tell their stories in full, but only recall them to the minds of those who are already acquainted with them. The paintings which represent the methodically arranged life of the Aztecs from childhood to old age, have more human interest about them than all the rest put together. In judging the Mexican picture-writings as a means of record, it should be borne in mind that though we can understand them to a considerable extent, we should have made very little progress in deciphering them, were it not that there are a number of interpretations, made in writing from the explanations given by Indians, so that the traditions of the art have never been wholly lost. Some few of the Mexican pictures now in existence may perhaps be original documents made before the arrival of the Spaniards, and great part of those drawn since are certainly copied, wholly or in part, from such original pictures.

It is to M. Aubin, of Paris, a most zealous student of Mexican antiquities, that we owe our first clear knowledge of a phenomenon of great scientific interest in the history of writing.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 9.This is a well-defined system of phonetic characters, which Clavigero and Humboldt do not seem to have been aware of, as it does not appear in their descriptions of the art.[14] Humboldt indeed speaks of vestiges of phonetic hieroglyphics among the Aztecs, but the examples he gives are only names in which meaning, rather than mere sound, is represented, as in the pictures of a face and water for Axayacatl, or "Water-Face," five dots and a flower for Macuilxochitl, or "Five-Flowers." So Clavigero gives in his list the name of King Itzcoatl, or "Knife-Snake," as represented by a picture of a snake with stone knives upon its back, a more genuine drawing of which is given here (Fig. 8), from the Le Tellier Codex. This is mere picture-writing, but the way in which the same king's name is written in the Vergara Codex, as shown in Fig. 9, is something very different. Here the first syllable, itz, is indeed represented by a weapon armed with blades of obsidian, itz(tli); but the rest of the word, coatl, though it means snake, is written, not by a picture of a snake, but by an earthen pot, co(mitl), and above it the sign of water, a(tl). Here we have real phonetic writing, for the name is not to be read, according to sense, "knife-kettle-water," but only according to the sound of the Aztec words, Itz-co-atl.

Fig. 10.Again, in Fig. 10, in the name of Teocaltitlan, which means "the place of the god's house," the different syllables (with the exception of the ti, which is only put in for euphony) are written by (b) lips, (c) a path (with footmarks on it), (a) a house, (d) teeth. What this combination of pictures means is only explained by knowing that lips, path, house, teeth, are called in Aztec, ten(tli), o(tli), cal(li), tlan(tli), and thus come to stand for the word Te-o-cal-(ti)-tlan. The device is perfectly familiar to us in what is called a " rebus," as where Prior Burton's name is sculptured in St. Saviour's Church as a cask with a thistle on it, "burr-tun." Indeed, the puzzles of this kind in children's books keep alive to our own day the great transition stage from picture-writing to word-writing, the highest intellectual effort of one period in our history coming down, as so often happens, to be the child's play of a later time.

Fig. 11.

M. Aubin may be considered as the discoverer of these phonetic signs in the Mexican pictures, or at least he is the first who has worked them out systematically and published a list of them.[15] But the ancient written interpretations have been standing for centuries to prove their existence. Thus, in the Mendoza Codex, the name of a place, pictured as in Fig. 11 by a fishing-net and teeth, is interpreted Matlatlan, that is "Net-Place." Now, matla(tl) means a net, and so far the name is a picture, but the teeth, tlan(tli), are used, not pictorially but phonetically, for tlan, place. Other more complicated names, such as Acolma, Quauhpanoayan, etc., are written in like manner in phonetic symbols in the same document.[16]

There is no sufficient reason to make us doubt that this purely phonetic writing was of native Mexican origin, and after the Spanish Conquest they turned it to account in a new and curious way. The Spanish missionaries, when embarrassed by the difficulty of getting the converts to remember their Ave Marias and Paternosters, seeing that the words were of course mere nonsense to them, were helped out by the Indians themselves, who substituted Aztec words as near in sound as might be to the Latin, and wrote down the pictured equivalents for these words, which enabled them to remember the required formulas. Torquemada and Las Casas have recorded two instances of this device, that Pater noster was written by a flag (pantli) and a prickly pear (nochtli), while the sign of water, a(tl), combined with that of aloe, me(tl), made a compound word ametl, which would mean "water-aloe," but in sound made a very tolerable substitute for Amen.[17]

Fig. 12.But M. Aubin has actually found the beginning of a Paternoster of this kind in the metropolitan library of Mexico (Fig. 12), made with a flag, pan(tli}, a stone, te(tl), a prickly pear, noch(tli), and again a stone, te(tl), and which would read Pa-te noch-te, or perhaps Pa-tetl noch-tetl.[18]

After the conquest, when the Spaniards were hard at work introducing their own religion and civilization among the conquered Mexicans, they found it convenient to allow the old picture-writing still to be used, even in legal documents. It disappeared in time, of course, being superseded in the long-run by the alphabet; but it is to this transition-period that we owe many, perhaps most, of the picture-documents still preserved. Copies of old historical paintings were made and continued to dates after the arrival of Cortes, and the use of records written in pictures, or in a mixture of pictures and Spanish or Aztec words in ordinary writing, relating to lawsuits, the inheritance of property, genealogies, etc., were in constant use for many years later, and special officers were appointed under government to interpret such documents. To this transition-period, the writing whence the name of Teocaltitlan (Fig. 10) is taken, clearly belongs, as appears by the drawing of the house with its arched door.

A genealogical table of a native family in the Christy Museum is as good a record of this time of transition as could well be cited. The names in it are written, but are accompanied by male and female heads drawn in a style that is certainly Aztec. The names themselves tell the story of the change that was going on in the country. One branch of the family, among whom are to be read the names of Citlalmecatl, or "Star-Necklace," and Cohuacihuatl, or "Snake-Woman," ends in a lady with the Spanish name of Justa; while another branch, beginning with such names as Tlapalxilotzin and Xiuhcozcatzin, finishes with Juana and her children Andres and Francisco. The most thoroughly native thing in the whole is a figure referring to an ancestor of Justa's, and connected with his name by a line of footprints to show how the line is to he followed, in true Aztec fashion. The figure itself is a head drawn in native style, with the eye in full front, though the face is in profile, in much the same way as an Egyptian would have drawn it, and it is set in a house as a symbol of dignity, having written over against it the high title of Ompamozcaltitotzaqualtzinco, which, if I may trust the imperfect dictionary of Molina, and my own weak knowledge of Aztec, means "His excellency our twice skilful gaoler."

The importance of this Mexican phonetic system in the History of the Art of Writing may he perhaps made clearer by a comparison of the Aztec pictures with the Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions consist of figures of objects, animate and inanimate, men and animals, and parts of them, plants, the heavenly bodies, and an immense number of different weapons, tools, and articles of the most miscellaneous character. These figures are arranged in upright columns or horizontal bands, and are to be read in succession, but they are not all intended to act upon the mind in the same way. When an ordinary inscription is taken to pieces, it is found that the figures composing it fall into two great classes. Part of them are to be read and understood as pictures, a drawing of a horse for "horse," a branch for "wood," etc., upon the same principle as in any savage picture-writing. The other part of the figures are phonetic. How they came to be so, seems plain from cases where we find the same picture sometimes used to stand for the object it represents, and sometimes for the sound of that object's name, after the manner just described of the rebus. Thus the picture of a star may represent a star, called in Egyptian sba, and the picture of a kid may stand for a kid, called in Egyptian ab; but these pictures may also be brought in to help in the spelling of the words sba, "door," and ab, "thirst," so that here they have passed into phonetic signs.[19] It is not always possible to distinguish whether a hieroglyph is used as a syllable or a letter. But it is clear that from an early period the Egyptians had chosen a number of hieroglyphs to be used as vowels and consonants to write words with, that is to say, they had invented alphabetic writing. Their use of hieroglyphs in all these stages, picture, syllable, letter, is of great interest in the history of writing, as giving the whole course of development by which a picture, of a mouth for instance, meant first simply mouth, then the name of mouth ro, and lastly dropped its vowel and became the letter r. Of these three steps, the Mexicans made the first two.

In Egyptian hieroglyphics, special figures are not always set apart for phonetic use. At least, a number of signs are used sometimes as letters, and sometimes as pictures, in which latter case they are often marked with a stroke. Thus the mouth, with a stroke to it, is usually (though not always) pictorial, as it were, "one mouth," while without the stroke it is r or ro, and so on. The words of a sentence are frequently written by a combination of these two methods, that is, by spelling the word first, and then adding a picture sign to remove all doubt as to its meaning. Thus the letters read as fnti in an inscription, followed by a drawing of a worm, mean "worm" (Coptic, fent], and the letters kk, followed by the picture of a star hanging from heaven, mean "darkness" (Coptic, kake). There may even be words written in ancient hieroglyphics which are still alive in English. Thus hbn, followed by two signs, one of which is the determinative for wood, is ebony; and tb, followed by the drawing of a brick, is a sun-dried brick, Coptic tôbe, tôbi, which seems to have passed into the Arabic tob, or with the article, attob, thence into Spanish through the Moors, as adobe, in which form, and as dobie, it is current among the English speaking population of America.

The Egyptians do not seem to have entirely got rid of their determinative pictures even in the latest form of their native writing, the demotic character. How it came to pass that, having come so early to the use of phonetic writing, they were later than other nations in throwing off the crutches of picture-signs, is a curious question. No doubt the poverty of their language, which expressed so many things by similar combinations of consonants, and the indefiniteness of their vowels, had to do with it, just as we see that poverty of language, and the consequent necessity of making similar words do duty for many different ideas, has led the Chinese to use in their writing determinative signs, the so-called keys or radicals, which were originally pictures, though now hardly recognizable as such. Nothing proves that the Egyptian determinative signs were not mere useless lumber, so well as the fact that if there had been none, the deciphering of the hieroglyphics in modern times could hardly have gone a step beyond the first stage, the spelling out of the kings' names.

We thus see that the ancient Egyptians and the Aztecs made in much the same way the great step from picture-writing to word-writing. To have used the picture of an object to represent the sound of the root or crude-form of its name, as the Mexicans did in drawing a hand, ma(itl), to represent, not a hand, but the sound ma; and teeth, tlan(tli), to represent, not teeth, but the sound tlan, though they do not seem to have applied it to anything but the writing of proper names and foreign words, is sufficient to show that they had started on the road which led the Egyptians to a system of syllabic, and to some extent of alphabetic writing. There is even evidence that the Maya nation of Yucatan, the ruins of whose temples and palaces are so well known from the travels of Catherwood and Stephens, not only had a system of phonetic writing, but used it for writing ordinary words and sentences. A Spanish MS., "Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan," bearing the date of 1561, and the name of Diego de Landa, Bishop of Merida, has been published by the Abbé Brasseur,[20] and contains not only a set of chronological signs resembling the figures of the Central American sculptures and the Dresden Codex, but a list of over thirty characters, some alphabetic, as a, i, m, n; some syllabic, as ku, ti; and a sentence, ma in kati, "I will not," written with them. The genuineness of this information, and its bearing on the interpretation of the inscriptions on the monuments, are matters for future investigation.

Yet another people, the Chinese, made the advance from pictures to phonetic writing, and it was perhaps because of the peculiar character of their spoken language that they did it in so different a way. The whole history of their art of writing still lies open to us. They began by drawing the plainest outlines of sun, moon, tortoise, fish, boy, hatchet, tree, dog, and so forth, and thus forming characters which are still extant, and are known as the Ku-wăn, or "ancient pictures."[21] Such pictures, though so much altered that, were not their ancient forms still to be seen, it would hardly be safe to say they had ever been pictures at all, are still used to some extent in Chinese writing, as in the characters for man, sun, moon, tree, etc. There are also combined pictorial signs, as water and eye for "tears," and other kinds of purely symbolic characters. But the great mass of characters at present in use are double, consisting of two signs, one for sound, the other for sense. They are called hing-shing, that is, "pictures and sounds." In one of the two signs the transition from the picture of the object to the sound of its name has taken place; in the other it has not, but it is still a picture, and its use (something like that of the determinative in the Egyptian hieroglyphics) is to define which of the meanings belonging to the spoken word is to be taken. Thus a ship is called in Chinese chow, so a picture of a ship stands for the sound chow. But the word chow means several other things; and to show which is intended in any particular instance, a determinative sign or key is attached to it. Thus the ship joined with the sign of water stands for chow, "ripple," with that of speech for chow, "loquacity," with that of fire, for chow, "flickering of flame;" and so on for "waggon-pole," "fluff," and several other things, which have little in common but the name of chow. If we agreed that pictures of a knife, a tree, an 0, should be determinative signs of things which have to do with cutting, with plants, and with numbers, we might make a drawing of a pear to do duty, with the assistance of one of these determinative signs, for pare, pear, pair. In a language so poverty-stricken as the Chinese, which only allows itself so small a stock of words, and therefore has to make the same sound stand for so many different ideas, the use of such a system needs no explanation.

Looking now at the history of purely alphabetical writing, it has been shown that there is one alphabet, that of the Egyptian hieroglyphics, the development of which (and of course of its derived forms) is clearly to be traced from the stage of pure pictures to that of pure letters. It was long ago noticed that some of the old Egyptian hieratic characters have been directly retained in use in Egypt. The Coptic Christians still keep up in their churches their sacred language, which is a direct descendant of the ancient Egyptian; and the Coptic alphabet, in which it is written and printed, was formed in early Christian times by adding to the Greek alphabet certain new characters to express articulations not properly belonging to the Greek. Among these additional letters, at least four are clearly seen to be taken from the old hieroglyphics, probably from their hieratic or cursive form, and thus to preserve an unbroken tradition at once from the period of picture-writing to that of the alphabet, and from times earlier than the building of the pyramids up to the present day.

It has long been known that the great family of alphabets to which the Roman letters belong with the Greek, the Gothic, the Northern Runes, etc., are to be traced back into connection with the Phœnician and Old Hebrew characters, the very word alphabet (alpha-bëta, aleph-beth) being an acknowledgment of the derivation from Semitic writing. But sufficient proof was wanting as to how these ancient Semitic letters came to be made. The theory maintained by Gesenius, that the Phœnician and Old Hebrew letters are rude pictures of Aleph the Ox, Beth the House, Gimel the Camel, etc., rested on resemblances which are mostly slight and indefinite. Also the supposition that the names of the letters date from the time when these letters were first formed, and thus record the very process of their formation, is a very bold one, considering that we know by experience how slight the bond is which may attach names to letters. Two alphabets, which are actually descended from that which is also represented by the Phœnician and Hebrew, have taken to themselves new sets of names belonging to the languages they were used to write, simply choosing for each letter a word which began with it. The names of our Anglo- Saxon Runes are Feoh (cattle, fee), Ûr (urus, wild ox), Thorn (thorn), Hägl (hail), Nead (need), and so on, for F, Û, Th, H, N, etc., this English list corresponding in great measure with those belonging to the Scandinavian and German forms of the Runic alphabet. Again, in the old Slavonic alphabet, the names of Dobro (good), Zemlja (land), Liodē (people), Slovo (word), are given to D, Z, L, S. Even if it be granted that there is an amount of resemblance between the letters and their names in the old Phœnician and Hebrew alphabets, which is wanting in these later ones, it does not follow from thence that the shape of the Hebrew letters was taken from their names. Letters may be named in two ways, acrostically, by names chosen because they begin with the right letters, or descriptively, as when we speak of certain characters as pothooks and hangers. A combination of the two methods, by choosing out of the words beginning with the proper letter such as had also some suitability to describe its shape, would produce much such a result as we see in the names of the Hebrew letters, and would moreover serve a direct object in helping children to learn them. It is easy to choose such names in English, as Arch or Arrowhead for A, Bow or Butterfly for B, Curve or Crescent for C; and we may even pick out of the Hebrew lexicon other names which fit about as well as the present set. Thus, though the list of names of letters, Aleph, Beth, Gimel, and the rest, is certainly a very ancient and interesting record, its value may lie not in its taking us back to the pictorial origin of the Hebrew letters, but in its preserving for us among the Semitic race the earliest known version of the "A was an Archer."

After the deciphering of the Egyptian hieroglyphs, it was seen to be probable that not only were the ancient Egyptians the first inventors of alphabetic writing, but that the Phœnician and Hebrew alphabet was itself borrowed from the Egyptian hieroglyph-alphabet. Mr. Samuel Sharpe made the attempt to bring together the Egyptian hieroglyphs in their pictorial form with the square Hebrew characters. The Vicomte de Rougé's comparison, left for years unpublished, of the Egyptian hieratic characters with the old Phœnician letters, confirms Mr. Sharpe's view as to the letters Vav and Shin (f and sh), and on the whole, though identifying several characters on the strength of too slight a resemblance, it lays what seems a solid foundation for the opinion that the main history of alphabetic writing is open to us, from its beginning in the Egyptian pictures to the use of these pictures to express sounds, which led to the formation of the Egyptian mixed pictorial, syllabic, and alphabetic writing, from which was derived the pure alphabet known to us in its early Phœnician, Moabite, and Hebrew stages, hence the Greek, Latin, and numerous other derived forms come down to modern times.[22]

It remains to point out the possibility of one people getting the art of writing from another, without taking the characters they used for particular letters. Two systems of letters, or rather of characters representing syllables, have been invented in modern times, by men who had got the idea of representing sound by written characters from seeing the books of civilized men, and applied it in their own way to their own languages. Some forty years ago a half breed Cherokee Indian, named Sequoyah (otherwise George Guess), invented an ingenious system of writing his language in syllabic signs, which were adopted by the missionaries, and came into common use. In the table given by Schoolcraft there are eighty-five such signs, in great part copied or modified from those Sequoyah had learnt from print; but the letter Ꭰ is to be read a; the letter Ꮇ, lu; the figure Ꮞ, se; and so on through Ꭱ, Ꭲ, Ꭵ, Ꭺ, and a number more.[23] The syllabic system invented by a West African negro, Momoru Doalu Bukere, was found in use in the Vei country, about fifteen years since.[24] When Europeans inquired into its origin, Doalu said that the invention was revealed to him in a dream by a tall venerable white man in a long coat, who said he was sent by other white men to bring him a book, and who taught him some characters to write words with. Doalu awoke, but never learnt what the book was about. So he called his friends together, and one of them afterwards had another dream, in which a white man appeared to him, and told him that the book had come from God. It appears that Doalu, when he was a boy, had really seen a white missionary, and had learnt verses from the English Bible from him, so that it is pretty clear that the sight of a printed book gave him the original idea which he worked out into his very complete and original phonetic system. It is evident from Fig. 13 that some part of the characters he adopted were taken, of course without any reference to their sound, from the letters he had seen in print. His system numbers 162 characters, representing mostly syllables, as a, be, bo, dso, fen, gba; but sometimes longer articulations, as seli, sediya, taro. Though it is almost entirely and purely phonetic, it is interesting to observe that it includes three genuine picture-signs, ꗬ gba, "money;" ꖜ bu, "gun," (represented by bullets,) and ꕀ chi, "water," this last sign being identical with that which stands for water in the Egyptian hieroglyphics.

It appears from these facts that the transmission of the art of writing does not necessarily involve a detailed transmission of the particular signs in use, and the difficulty in tracing the origin of some of the Semitic characters may result from their having been made in the same way as these American and African characters. If this be the case, there is an end of all hope of tracing them any further.

In conclusion, it may be observed that the art of picture-writing soon dwindles away in all countries when word-writing is introduced, yet there are a few isolated forms in which it holds its own, in spite of writing and printing, at this very day. The so-called Roman numerals are still in use, and I II III are as plain and indisputable picture-writing as any sign on an Indian scroll of birch-bark. Why V and X mean five and ten is not so clear, but there is some evidence in favour of the view that it may have come by counting fingers or strokes up to nine, and then making a stroke with another across to mark it, somewhat as the deaf-and-dumb Massieu tells us that, in his untaught state, his fingers taught him to count up to ten, and then he made a mark. Loskiel, the Moravian missionary, says of the Iroquois, "They count up to ten, and make a cross; then ten again, and so on, till they have finished; then they take the tens together, and make with them hundreds, thousands, and hundreds of thousands."[25] A more modern observer says of the distant tribe of the Creeks, that they reckon by tens, and that in recording on grave-posts the years of age of the deceased, the scalps he has taken, or the war-parties he has led, they make perpendicular strokes for units, and a cross for ten.[26] The Chinese character for ten is an upright cross; and in an old Chinese account of the life of Christ, it is said that "they made a very large and heavy machine of wood, resembling the character ten," which he carried, and to which he was nailed.[27] The Egyptians, in their hieroglyphic character, counted by upright strokes up to nine, and then made a special sign for ten, in this respect resembling the modern Creek Indians, and the fact that the Chinese only count 〡〢〣 in strokes, and go on with an 〤 for four, and then with various other symbols till they come to 〸 or ten, does not interfere with the fact, that in three or four systems of numeration, so far as we know independent of one another, in Italy, China, and North America, more or less of the earlier numerals are indicated by counted strokes, and ten by a crossed stroke. Such an origin for the Roman X is quite consistent with a half X or V being used for five, to save making a number of strokes, which would be difficult to count at a glance.[28]

However this may be, the pictorial origin of I II III is beyond doubt. And in technical writing, such terms as T-square and S-hook, and phrases such as "☉ before clock 4 min.," and "☽ rises at 8h. 35m.," survive to show that even in the midst of the highest European civilization, the spirit of the earliest and rudest form of writing is not yet quite extinct.

- ↑ Figs. 2 to 7, and their interpretations, are from Schoolcraft 'Indian Tribes,' part i. See also the 'Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner,' edited by Edwin James, 1830, from which many of Schoolcraft's pictures and interpretations seem taken.

- ↑ Catlin, 'North American Indians,' 7th ed.; London, 1848, vol. ii. p. 98.

- ↑ Catlin, vol. ii. p. 170.

- ↑ Lord Kingsborough, 'Antiquities of Mexico;' London, 1830, etc., vol. iv. part i., no. 31, and vol. v. Expl.

- ↑ Humboldt and Bonpland, vol. ii. p. 239.

- ↑ Gustav Klemm, 'Allgemeine Cultur-Geschichte der Menschheit;' Leipzig, 1843–52, vol. iv. p. 396.

- ↑ Rivero and v. Tschudi, 'Antigüedades Peruanas;' Vienna, 1851, p. 124. Prescott, 'Peru;' vol. i. p. 116.

- ↑ Schoolcraft, part i. pp. 334, 353; part iii. pp. 256, 485. Harmon, 'Journal; Andover, 1820, p. 371. Klemm, C. G., vol. ii. pp. 189, 280.

- ↑ Birch, in 'Archæologia,' vol. xxxiv. p. 382.

- ↑ Herod, v. 49.

- ↑ Harmon, p. 371.

- ↑ 'Journal des Sçavans,' 1681, p. 46. Sir W. Talbot, 'The Discoveries of John Lederer;' London, 1672, p. 4. Humboldt, 'Vues des Cordillères;' Paris, 1810–12, pl. xiii.

- ↑ Tylor, 'Mexico and the Mexicans;' London, 1861, p. 239.

- ↑ Clavigero, 'Storia Antica del Messico;' Cesena, 1780–1, vol. ii. pp. 191, etc., 248, etc. Humboldt, 'Vues des Cord.,' pl. xiii.

- ↑ Aubin, in 'Revue Orientale et Américaine,' vols, iii.–v. Brasseur, 'Hist. des Nat. Civ. du Mexique et de l'Amériqne Centrale;' Paris, 1857–9, vol. i. An attempt to prove the existence of something more nearly approaching alphabetic signs (Rev., vol. iv. p. 276–7; Brasseur, p. lxviii.) requires much clearer evidence.

- ↑ Kingsborough, vol. i., and Expl. in vol. vi.

- ↑ Brasseur, vol. i. p. xli.

- ↑ Aubin, Rev. O. and A., vol. iii. p. 255.

- ↑ Renouf, 'Elementary Grammar of the Ancient Egyptian Language,' London, 1875.

- ↑ Brasseur, 'Relation des Choses de Yucatan de Diego de Landa,' etc.; Paris and London, 1864.

- ↑ J. M. Callery, 'Systema Phoneticum Scripturæ Sinicæ,' part i.; Macao, 1841, p. 29. Endlicher, Chin. Gramm., p. 3, etc.

- ↑ Sharpe, 'Egyptian Hieroglyphics;' London, 1861, p. 17. Vte. Em. de Rougé, 'Mémoire sur l'Origine Egyptienne de l'Alphabet Phénicien,' Paris, 1874. In former editions of the present work, the Egyptian origin of the alphabet was only treated as a likely supposition. In consequence of the appearance of M. de Rougé's argument since, the text has been altered to embody the now more advanced position of the subject. [Note to 3rd Edition.]

- ↑ Schoolcraft, part ii. p. 228. Bastian, vol. i. p. 423.

- ↑ Koelle, 'Grammar of the Vei Language;' London, 1854, p. 229, etc. J. L. Wilson, 'Western Africa;' London, 1856, p. 95.

- ↑ Loskiel, Gesch. der Mission der evangelischen Brüder; Barby, 1789, p. 39.

- ↑ Schoolcraft, part i. p. 273.

- ↑ Davis The Chinese; London, 1851, vol. ii. p. 176.

- ↑ A dactylic origin of V, as being a rude figure of the open hand, with thumb stretched out, and fingers close together, succeeding the I II III IIII, made with the upright fingers, has been propounded by Grotefend, and has occurred to others. It is plausible, but wants actual evidence.