IV

The Image Prints of the Fifteenth Century.

Were Engraved on Wood…Print of St. Christopher…Print of Annunciation…Print of St. Bridget. Other German Engravings on Wood…Flemish Indulgence Print…The Brussels Print…The Berlin Print…All Image Prints from Germany or the Netherlands…How were they Printed? Not by the Frotton…Methods of taking Proof now used by Engravers and Printers…Images copied from Illustrated Manuscripts…Not made by Monks…Images highly prized by the People…The Beginning of Dissent in the Church…Preceded by Ruder Prints.

Woltmann

ONE of the purposes to which early printing was applied was the manufacture of engraved and colored pictures of sacred personages. These pictures, or image prints, as they are called by bibliographers, were made of many sizes; some of them are but little larger than the palm of the hand, others are of the size of a half sheet of foolscap. In a few prints there are peculiarities of texture which have provoked the thought that they may have been printed from plates of soft metal like lead or pewter; but this conjecture has never been verified. We find in many of the prints the clearest indications that they were taken from engravings on wood. With a few exceptions, these prints were colored; some were painted, but more were colored by means of stenciling, as is abundantly proved by the mechanical irregularities which are always produced by the occasional slipping of the stencil. The colors are gross, glaring, and so inartistically applied that the true outlines of the figures are frequently obscured.

The Print of St. Christopher.

Size of original 8½ by 11¼ inches.The quality of the engraving is unequal; some prints are neatly, and others are rudely cut, but in nearly all of them the engraving is in simple outline. We seldom see any shading tints, or any cross-hatchings, rarely ever any attempt to produce a perspective by the use of fine or faint lines. The absence of shading lines is not entirely due to the imperfect skill of the engravers. The engravings seem to have been cut for no other purpose than that of showing the colors of the stencil painter to advantage, by giving a definite edge to masses of color. The taste for prints in black and white had not then been developed. To the print-buyer of the fifteenth century, the attraction of the image print was not in its drawing, but in its vivid color, and its supposed resemblance to the paintings that adorned the walls of churches and monasteries. The image print of the fifteenth century was the prototype of the modern chromo.

The St. Christopher, a bold and rude engraving on wood, which represents the saint in the act of carrying the infant Saviour across a river, is one of the most remarkable of the image prints. This print was discovered in the cover of an old manuscript volume of 1417, among the books of one of the most ancient convents of Germany, the Chartreuse at Buxheim, near Memmingen, in Suabia.[1] The monks said that the volume was given to the convent by Anna, canoness of Buchau, who is known to have been living in 1427. The name of the engraver is unknown. This convent is about fifty miles from Augsburg, a city which seems to have been the abode of some of the early engravers on wood. The date is obscurely given in Roman numerals at the foot of the picture.

| Christoferi faciem die quacunque tueris, | Millesimo cccc. |

| Ella nempe die morte mala non moreiris. | rr° tertio. |

| In whatsoever day thou seest the likeness of St. Christopher, In that same day thou wilt at least from death no evil blow incur. |

1423. |

The date 1423 is evidence only so far as it shows that the block was engraved in that year. The printing could have been done at a later date. As it is printed in an ink that is almost black (in which feature it differs from other early image prints, that are almost invariably in a dull or faded brown ink), there is reason to believe that this print was made some time after the engraving, when the method of making prints with permanent black ink was more common.

This engraving has its merits as well as its absurdities. Chatto says that the design is better than any he has found in the earlier type-printed books; that the figure of the saint and that of the youthful Christ are, with the exception of the extremities, designed in such a style that they would scarcely discredit Albert Durer himself.

The accessories are grotesquely treated. One peasant is driving an ass with a loaded sack to a water-mill; another is toiling with a bag of grain up a steep hill to his house; another, to the right, holds a lantern. The relative proportions of these figures are but a little less absurd than those made famous in Hogarth's ironical study of false perspective.

The AnnunciationThese faults of drawing are counterbalanced by real merits of engraving. There is a noticeable thickening and tapering of lines in proper places, a bold and a free marking of the folds of drapery, and a general neatness and cleverness of cutting that indicate the hand of a practised and judicious engraver. This engraving of St. Christopher is obviously not the first experiment of an amateur or an untaught inventor.

In the book which contained this print of the St. Christopher was also found, pasted down within the cover, another engraving on wood, that is now known as the Annunciation. It is of about the same size as the print of St. Christopher. It is printed on the same kind of paper, with the same dull black ink. There is some warrant for the general belief that both engravings were executed at or about the same time, but they are so unlike that they cannot be considered as the work of the same designer nor of the same engraver. The lines of the Annunciation are more sharply cut; the drawing has more of detail; there are no glaring faults of perspective.

The Virgin is represented as receiving the salutation of the angel Gabriel; the Holy Spirit descends in the shape of a dove proceeding from a part of the print which has been destroyed, and in which was some symbol of the Almighty. The black field in the centre of the print was left unrouted by the engraver, apparently for no other purpose than that of lightening the work of the colorist, who would otherwise have been required to paint it black. This method of producing the full blacks of a colored print was practised by many of the early engravers. Full black shoes on the feet of human figures may be noticed in many of Caxton's woodcuts while other portions of the print are in outline. There are portions of this print in which the practical engraver will note an absence of shading where shades seem to be needed. The body of the Virgin appears as naked, except where it is covered by her mantle. It was intended that an inner garment should be indicated by the brush of the colorist. What the early engravers on wood could not do with the graver, they afterward did with the brush. They not only printed but colored their prints, and the colored work was usually done in a free and careless manner.

These prints do not contain internal evidences of their origin. They were found in Germany, but there is nothing in the designs, nor yet in their treatment, that is distinctively German. The faces and costumes reveal to us no national characteristics; the legends are in Latin; the architecture of the Annunciation is decidedly Italian.

But there is a print known as the St. Bridget, a print supposed to be of nearly the same age as the St. Christopher, which gives us at least an indication of the people by whom it was purchased and of the country in which it was printed.

St. Bridget.Saint Bridget of Sweden, born 1302, died 1373, was one of the chosen saints of Germany. The print represents her as writing in a book while the Virgin and the infant Christ look down approvingly. The letters S. P. Q. R. on the shield, and the pilgrim's hat, staff and scrip are supposed to indicate her pilgrimages to Rome and Jerusalem. The armorial shield has the arms of Sweden. The legend, if it can be so called, at the top of the print is in German: O Brigita bit got für uns.—O, Bridget, pray to God for us. The letters M. I. Chrs at the bottom of the print have been construed as, Mother of Jesus Christ.

The lines of this print are of a dull brown color. The face and hands are of flesh color, the gown, hat and scrip are dark grey; the desk, the staff, letters, lion and crown, as well as the glory or nimbus about the head, are yellow. The ground is green, and the whole cut is surrounded with a border of shining lake or mulberry color. This harsh arrangement of the colors is a proper illustration of the inferiority of the workmanship of the colorist to that of the designer.

Other prints in European libraries have been attributed to unknown engravers of Germany, who are supposed to have practised their art between the years 1400 and 1450. One of these prints, to which is attached a short prayer and the date of 1437, and which was discovered in a monastery in the Black Forest near the border of Suabia,[2] represents the martyrdom of St. Sebastian. These prints are rare: of the St. Christopher only three copies are known;[3] of the St. Bridget and Annunciation there is but one copy each. All of them were discovered in German religious houses, in which places it seems that they have been preserved ever since they were printed. They were found in a part of Germany that is famous as the abode of early engravers on wood, and as the birthplace of several great German artists. Prints of a similar nature were subsequently made in Germany in greater quantity than in any other part of Europe. The legend of St. Bridget is in German; the costumes of the archers in St. Sebastian are German. They are trustworthy evidences in favor of the hypothesis that engraving on wood was first practised in Germany.

This hypothesis has been disputed. It is opposed by several contradictory theories, which may be stated in the following words: (1) that engraving on wood was applied to the manufacture of playing cards in France at the end of the fourteenth century; (2) that it was derived from China; (3) that it was invented in Italy; (4) that it was practised in the Netherlands before it was known in Germany. As the theories of French, Chinese and Italian origin have no early prints of images to offer, they need not be considered in this chapter. The argument in favor of a very early practice of engraving in the Netherlands is based on its prints of images.

The Flemish Indulgence Print.

The illustration on the opposite page is the reduced fac-simile of an old print once known as the Indulgence Print of 1410, and then considered as of greater age than the print of Saint Christopher. The inscription at the foot of the indulgence; which is in old Dutch or Flemish, is to this effect:

"Whoever, regarding the sufferings of our Lord, shall truly repent of his sins, and shall thrice repeat the Pater Noster and the Ave Maria, shall be entitled to seventeen thousand years of indulgence, which have been granted to him by Pope Gregory, as well as by two other popes and by forty bishops. [This has been done so that] the rich as well as the poor may try to secure this indulgence."

That this print was made in Flanders is apparent from the language, as well as from the peculiar shape of the letter t at the end of words. The perpendicular bar dropping from the top of this t was so seldom used in Germany that it may be regarded as a very old Flemish mannerism. That the print was engraved in 1410 is extremely improbable. The Pope Gregory here mentioned is undoubtedly Pope Gregory xii, who reigned from 1406 to 1415. It was once believed that the two other popes mentioned in the indulgence were the rivals of Gregory, the anti-popes Benedict xii and John xxii. It was supposed that this print was published during this period,[4] and for this reason, it has sometimes been called the Indulgence Print of 1410.

M. Wetter, a learned German critic, has pointed out the absurdity of the belief that three popes at enmity with each other should unite in the promulgation of this document.[5] It is now understood that the two other popes mentioned in the indulgence are Pope Nicholas v, who reigned from 1447 to 1455, and Pope Calixtus iii, who reigned from 1455 to 1458. The publication of the indulgence is therefore placed between the years 1455 and 1471. Consequently, the print is of no value as an evidence of Flemish priority, for it was made more than thirty years after the St. Christopher.

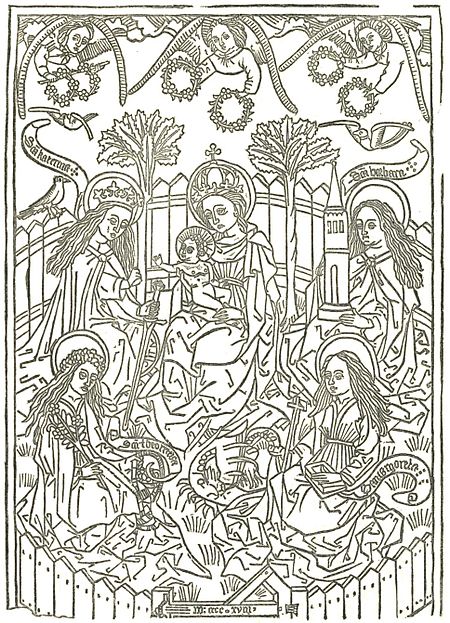

A much more satisfactory evidence of the great age of Flemish engraving on wood is afforded by the Brussels Print, which was discovered in 1848 by an innkeeper, pasted down on the inside of an old chest. It was bought by an architect of the town of Mechlin, who sold it for five hundred francs to the Royal Library of Brussels, where it is now preserved. This print bears the date 1418, but the validity of the date has been challenged. It was alleged that the numerals that form the date had been repaired with a lead pencil in such a manner as to provoke doubts of its genuineness; that the true date is 1468, instead of 1418; that an alteration was made, by scratching out the L from the middle of the numerals [thus, mcccc(l)xviii] and by substituting a period—a fraud that puts the date backward fifty years. The charge of fraud has been denied with ability, and seemingly with justice. The print has passed the ordeal of hostile criticism, and is now accepted as a genuine print of 1418. It represents the Virgin and infant Saviour, when surrounded by St. Barbara, St. Catharine, St. Veronica and St. Margaret. The design is somewhat stiff and mechanical, but the composition is not devoid of merit. The lines of the engraving were purposely broken, for it was intended that the print should be more fully developed by the bright colors of the stencil painter. The fac-simile is taken from Holtrop's Monuments typographiques. Holtrop says that the fac-simile is slightly reduced in height. The size of the block, as he represents it, is 9⅞ by 13¾ American inches.

The Brussels Print.

The Flemish origin of the Brussels Print is established by an image, in the Cabinet of Engravings at Berlin, now known as the Berlin Print. It is of the same size as the Brussels Print, and is, apparently, the work of the same designer, for in these prints a remarkable similarity of treatment in designing and engraving may be noticed in the wings of the angels, in the figure and position of the angel who crowns the Virgin, in the crowns of St. Catharine and the Virgin, in the flowing hair of the three saints, and that of the Virgin, and in the collars on the doves. This print represents the Virgin as carrying in her arms the infant Saviour. It is described in the catalogue as an early xylographic engraving, printed by friction about the middle of the fifteenth century. It is without date or name of artist. The language of the legend is Flemish. The Virgin holds in her right arm the infant Jesus, and in her left hand an apple. The child caresses the chin of his mother with one hand, while he drops a rose from the other. The Virgin, enshrined in an aureole of glory, encircled by four angels and four doves, placidly stands upon a crescent. The legend in the four corners is in metre, and is an exhortation to the reader to serve the Virgin, and imitate her example.

Who is this queen who is thus exalted?

She is the consolation of the world.

What is her name? tell me, I pray!

Mary, blessed Mother and Virgin.

How did she attain this exaltation?

By love, humility and charity.

Who will be uplifted with her, on high?

Whoever knows her best in life.

Connoisseurs in prints disagree as to the age and merit of this print. Passavant says that the Berlin Print, which he sescribes as of fine execution, is undoubtedly of Dutch origin, but he thinks it is the design of a German artist. He places its date in the same period as that of the Brussels Print, which, according to him, is 1468. Renouvier says that the outlines of the Berlin Print are in the style of well-known Dutch or Flemish prints. He hazards no conjecture as to the exact date of its publication, but intimates that it may properly be classified with the older prints of the Netherlands.

The Berlin Print.

Holtrop says that the language of the legend in the Berlin print decides its origin; the design is of the Netherlandish school; the language is Flemish, and not Dutch. He further says: "These two prints (of Berlin and Brussels) complement each other; the print of Berlin shows their common origin; the print of Brussels indicates their date. It may be said that they were engraved in the Netherlands, probably in Flanders, and perhaps in Bruges, at the beginning of the fifteenth century."

The prints herein described are the earliest prints with dates, but they are not, necessarily, the earliest of all. There are prints known to collectors as the Crucifixion, the Last Judgment and the St. Jerome, which are regarded by many bibliographers as the work of unknown engravers at or about 1400. There is a print of St. George which competent judges say was done in the thirteenth century. None of the prints contain the name or the place of the engravers, but it is plain that they were made in the Southern Netherlands, as well as in Southern Germany. It would be premature to assume that they were made nowhere else; but it must be acknowledged that there are no image prints on paper which can be ascribed to any engraver in France, Italy, Spain, Holland or England, during the first fifty years of the fifteenth century. There is a plausible statement on record, which will be reviewed on another page, that artistic engravings on wood were made in Italy before this period. We find, also, a more questionable statement, that engraving on wood was practised in France before the year 1400—a statement based entirely on a print in the public library of the city of Lyons, with a printed date which has been represented as that of the year 1384. The age of this print has been denied. It is alleged, with every appearance of probability, that there is mistake or fraud in the numerals, for the costumes of the figures prove that the print should have been made in the sixteenth century.

The question whether image prints were first made in the Netherlands or in Suabia need not now be considered. It is enough to say that, although the Brussels print bears the earliest date, the manufacture of these image prints was more common in Germany, not only in the first but in the latter half of the fifteenth century. That these few accidentally discovered prints represent the half, or even one-tenth, of the images then published, is not at all probable. We have good reason for the belief that they were as abundant in Southern Germany during the year 1450 as cheap lithographs were in the United States during the year 1830. That the greater part of these image prints have been destroyed and forgotten may be explained by the improved taste of the succeeding generation. The artistic copper-plate prints which came in fashion soon after swept away as rubbish the once admired image prints, just as the chromos of this period have supplanted the painted lithographic prints of 1830.

How were these images printed? Almost every author who has written on printing has said that they were printed by friction, with a tool known as the frotton, which has been described as a small cushion of cloth stuffed with wool. It is said that when the block had been inked, and the sheet of paper had been laid on the block, the frotton was rubbed over the back of the sheet until the ink was transferred to the paper. We are also told that the paper was not dampened, but was used in its dry state. The shining appearance on the back of the paper is offered as evidence of friction. This explanation of the method used by the printers of engraved blocks has been accepted, not as a conjecture, but as the description of a known fact. I know of no good authority for it. I know no author who professes to have seen the process. I know no engraver who has taken impressions with a cloth frotton. I doubt the feasibility of the method. The reasons for this doubt will be apparent when this conjectural method is contrasted with the methods used by modern printers and engravers for taking proofs off of press.

The modern engraver on wood takes his proofs on thin India paper. He uses a stuffed cushion to apply the ink to the cut. The ink, which is sticky, serves to make thin paper adhere to the block. He gets an impression by rubbing the back of the paper after it is laid on the block, with an ivory burnisher. If he is careful, he can take with a burnisher a neater proof than he could get from a press. But the only point of similarity between the imaginary old process and the present process is in the method of rubbing or friction. The materials are different: the modern paper is thin and soft, the old was coarse and harsh; modern ink is glutinous, medieval ink was watery; the burnisher is hard, the frotton was very elastic; the burnisher will give a shining appearance to the back, the soft frotton will not. If the modern engraver should attempt to use coarse, thick, dry paper, fluid ink, and a cloth frotton, he could not keep the sheet in place on the block during the slow process of rubbing. No care could prevent it from slipping when rubbed with an elastic cushion. The least slip would produce a distorted impression.

The modern printer takes his proof on dampened paper with a tool known as the proof-planer. This proof-planer is a small thick block of wood, one side of which is perfectly flat and covered with thick cloth. When the paper, which must be dampened, has been laid on the inked type or engraving, the printer places the planer carefully on the paper, holding it firmly with his left hand; with a mallet, held in his right hand, he strikes a strong hard blow on the planer. He then lifts his planer carefully and places it over the nearest unprinted surface and repeats the blow. In like manner he repeats the blow until every part of the type surface has been printed. Rude as this method may seem, a skillful workman can obtain a fair print with the planer. Although the wet paper clings to the type, and the ink is sticky, great care is needed to prevent the slipping of the sheet, and the doubling of the impression. The back of a thick sheet printed in this manner often shows a shining appearance in the places where the blow was resisted by the face of the type or by the engraved lines.

It will be seen that the printer's method of taking proof differs in all its details from the supposititious method of the early engravers. We have soft, damp paper, sticky ink, and a sudden flat pressure against a hard surface shielded with cloth, in opposition to fluid ink, dry paper, rubbing pressure and an elastic printing tool.

As we can find no positive knowledge of the method of printing which was adopted by the early printers of engravings on wood, it is somewhat hazardous to offer conjectures in place of facts. It is begging the question to assume that they were not printed by a press. The presswork of early prints is coarse and harsh, and could have been done with simple mechanism, with rude applications of the screw or of the lever, that could have been devised by any intelligent workman. It is more reasonable to assume that the early prints were made by a press, or with some practicable tool like a proof-planer, rather than with the impracticable frotton. One cannot resist the suspicion that the chronicler of early block printing who first described the frotton attempted to describe what he did not thoroughly understand—that he mistook the engraver's inking cushion for the tool by which he got the impression.

It should be noticed that all these old prints are of a religious character. Portraits of remarkable men or women, landscapes, representations of cities or buildings, caricatures, illustrations of history or mythology—none of these are to be found in any collection of the earliest prints. The early engravers were completely under the domination of religious ideas. Their prints seem to have been made with the permission, and possibly under the direction, of proper clerical authority. The designs are of much greater merit than any that could have been created by amateurs in the art of engraving on wood. They were, undoubtedly, copied from the illuminated books of piety which were then to be found in all large monasteries. Ecclesiastics of this period were careful of their books and jealous of their privileges, and not disposed to allow either to become cheap or common, but they must have favored an art that multiplied the images of patron saints. It was an age of great disbelief, and the image prints were of service as reminders of religious duty.

There is no evidence that these prints were made by the monks themselves. There is a statement current in German books of bibliography that one Luger, a Franciscan monk in Nordlingen, engraved on wood at the end of the fourteenth century. But this statement needs verification. It is not at all certain that the word which is here translated engraver on wood was written with clear intention to convey this meaning. The earliest typographers were not monks, nor were they favored with the patronage of the church.[6] It is not probable that any monk who had been educated for the work of a copyist or an illuminator, would forsake his profession for the practice of engraving on wood or printing. Prints, as then made, were coarse, mechanical copies of meritorious originals. The artistic scribe rightfully felt that engraving was beneath him. He must have looked on the people who bought image prints with the same pitying scorn that a true artist feels for the uneducated taste of those who now buy glaring lithographs of sacred personages, and he must have felt as little inducement to engage in their manufacture.

And yet the multitude received them gladly. Wealthy laymen who could afford to buy gorgeous missals, and priests who daily saw and handled manuscript works of art, might put the prints aside as rubbish; but poor men and women, whose work-day lives were unceasing rounds of poverty and drudgery, unrelieved by art, ideality or sentiment, must have hailed with gladness the images in their own houses which shadowed ever so dimly the glories of the church and the rewards of the righteous. The putting-up of the image print on the wall of the hut or the cabin was the first step toward bringing one of the attractions of the Catholic church within the domestic circle. It was the erection of a private shrine, an act of rivalry, pitiable enough in its beginning, but of great importance in its consequences. For it was the initiation of the right of private judgment, and of the independence of thought which, in the next century, made itself felt in the formidable dissent known in all Protestant countries as the Great Reformation.

Our knowledge of the origin of engraving on wood has not been materially increased by the recent discovery of the Berlin and Brussels Prints. We see that wood-cuts of merit were made during the first quarter of the fifteenth century, but we see also that they could not have been the first productions of a recently discovered or newly revived art. They present indications of a skill in engraving which could have been acquired only through experience. One has but to compare them with wood-cuts made by amateurs in typographic printing in Italy, Germany and Holland between the years 1460 and 1500, to perceive that the manufacturers of the image prints were much more skillful as engravers. If there were no other evidences, we could confidently assume that this skill could have been acquired only by practice on ruder and earlier engravings. Of this preliminary practice-work we find clear traces in the stenciled and printed playing cards which were popular in many parts of Europe before the introduction of images.

- ↑ Heineken, Idée générale d'une collection complette d'estampes, avec une dissertation, etc., p. 250.

According to the legend, it was the occupation of Saint Christopher to carry people across the stream on the banks of which he lived. He is accordingly represented as a man of the weight of gigantic stature and strength. One evening a child presented himself to be carried over the stream. At first his weight was what might be expected from his infant years; but presently it began to increase, and kept increasing, until the ferryman staggered under his burden. Then the child said, "Wonder not, my friend; I am Jesus, and you have the sins of the whole world on your back." St. Christopher was thus regarded as a symbol of the church.

- ↑ The Suabia of the fifteenth century was separated by the Rhine from Switzerland and France on the south and west; its eastern boundary was Bavaria; its northern boundary, Franconia and the Palatinate of the Rhine.

- ↑ As these three copies have never been compared side by side, it has not been proven that they are impressions from the same block. The copy described on a preceding page has some peculiarities not found in the others.

- ↑ A book printed at Delft in 1480, says that when St. Gregory was pope, he celebrated mass in the church Porta Crucis. As he was consecrating the bread and wine, Christ appeared to him as represented in the engraving, with all the accessories to his passion. Robert of Cologne, who wrote a treatise on indulgences, published at Zutphen in 1518, adds, that Pope Gregory kindly granted 14,000 years of indulgence; that Pope Nicholas V doubled them; that Pope Calixtus, after requiring the repetition five times of the prayers, again doubled the years of indulgence; that Pope Innocent VIII, after adding seven more prayers, two other prayers, and two more of the Pater Noster and the Ave Maria, again doubled the length of indulgence—so that the sum total amounted to at least 70,000 years: according to other computations, to 92,000 years, or 112,000 years. Holtrop, Monuments typographiques, p. 13. There is but one copy of this print, which recently belonged to the collection of Theodor O. Weigel of Leipsic, who published a fac-simile of it in colors, in his great work, The Infancy of Printing, plate 113, vol. 1.

- ↑ Wetter says that all letters of indulgence for thousands of years are spurious; that they were made by monks and ignorant traveling priests for no other purpose than to allure simple people to church.

- ↑ Sweinheym and Pannartz, who were invited, in 1464, to establish a printing office in the monastery of Subiaco near Rome, were the first printers connected with any ecclesiastical institution. It may be remarked, that they did not thrive under clerical favor, for they soon found it expedient to remove to the city of Rome, where they were equally unfortunate in their efforts to find purchasers for their books.