The New Forest: its history and its scenery/Chapter 6

CHAPTER VI.

BEAULIEU ABBEY.

I should trust that, on a fine day, twenty miles are not too much for any Englishman. If they are, and any one should think the walk along the coast too long, Beaulieu may be reached by going direct from Hythe, across Beaulieu Common. The moor stretches out on all sides, flushed in the summer with purple heather, northward to the Forest, southward to the cultivated fields round Leap and Exbury. Passing "The Nodes,"[1] the road runs quite straight to Hill Top, with its clump of firs, which we reached in the last chapter.

Down in the valley, hid from us by a turn in the road, lies Beaulieu. But a little farther on we reach part of the old Abbey walls, broken here and there, clustered with ivy, and grass, and yellow mullein, and white yarrow, whilst vine-clad cottages stand against its sides. The village is situated on a bend of the Exe, where, spanned by a bridge, the stream falls over the weir, formerly turning the old mill-wheel of the monks, and then, broadening with the tide, winds through meadows and thick oak copses down to the Solent.

Although far more beautifully situated, the Abbey is not nearly so well known as its own filial house at Netley, simply because more out of the way. For a moment let us give some account of its foundation, illustrating as it does both King John's cruelty and superstition. The story, as told by the monks, is that John, after various oppressions of the Cistercian Order, in the year 1204, convened their abbots to his Parliament at Lincoln. As soon as they came, he ordered his retainers to charge them on horseback. No one was found to obey such a command. The monks fled to their lodgings. That night the King dreamt he was led before a judge, who ordered him to be scourged by these very monks. The next morning John narrated his dream, which was so vivid that he declared he felt the blows when he awoke, to a priest of his court, who told him that God had been most merciful in thus simply chastising him in this world, and revealing the secrets of His will. He advised him at once to send for the abbots, whom he had so ill-treated, and to implore their pardon.[2]

Some truth, doubtless, underlies this story. Certain it is that in the same year, or the next, John founded the Abbey at Beaulieu, then Bellus Locus, so called from its beauty, placing there thirty monks from St. Mary's, at Citeaux, endowing it with land in the New Forest, and manors, and villages, and churches in Berkshire; exempting it from various services and taxes and tolls; giving further, out of his own treasury, a hundred marks; and ordering all other Cistercian Houses to assist in the work. Not only did he do this, but he revoked his gift of the manor of Farendon, which, in the previous year, he had conditionally bestowed on some other Cistercian monks, and now transferred it to Beaulieu, making the House at Faringdon a mere offshoot from the larger building.[3] And the abbot designate repaid him in his life-time by accusing his enemy, Stephen of Canterbury, before the Pope, for treason, and causing him to be suspended.[4]

John died, and Henry III. not only confirmed the privileges, but granted several more in consideration of the great expense of the building, and Innocent III., gave it the right of a sanctuary. So the work proceeded. The stone was quarried principally from the opposite limestone-beds in the Isle of Wight; and was brought over, says tradition, curiously illustrating the vague notions of ancient geography, which we have seen in Diodorus Siculus,[5] in carts. Not, however, till 1249, some forty-five years after its foundation, was the monastery finished. Henry himself, and his Queen, and Richard, Earl of Cornwall, and a long train of nobles and prelates, came to its dedication on the feast of St. John; Hugh, the first abbot, spending no less than five hundred marks on the entertainment.[6]

So, at last, the good work was accomplished, and men came here and lived, taking for their pattern the holy St. Benedict, and finding the problem of life solved by daily prayer to heaven and labour on earth.[7]

Here, to its sanctuary, in 1471, after she had landed at Southampton on Easter Day, the very day of the battle of Barnet, fled the Countess of Warwick, wife of the King-maker, slain on that bloody field.[8] Here, too, in 1497, after having raised the siege of Exeter, and deserting his troops at Taunton, fled the worthless Perkin Warbeck, not only an impostor, but a coward, closely pursued by Lord Daubeny and five hundred men. Persuaded, however, by Henry VII.'s promises, he left his shelter only to become a prisoner in the Tower, and finally to expiate his deceit at Tyburn.

So years passed at the Abbey, the monks happy in saying their daily prayers, content to see the corn grow, and their vineyards ripen, and their flocks increase, knowing little of the troubles which raged in the outer world, save when some forlorn fugitive arrived. But even what is best becomes the worst. Time brought a change of spirit on all the monasteries. Long before the middle of the sixteenth century the stern earnestness of a former age had dwindled into effeminacy and sensuality. Piety had sunk into gross idolatry; and faith, amongst the laity, had been corrupted into credulity, and, with the priests, into hypocrisy. The greatest blessings had festered into curses. It was so, we know, through all England. And Beaulieu must suffer with the rest of the monasteries.

In 1587, the Abbey was dissolved, the last Abbot, Thomas Stephens, with twenty out of the thirty monks, signing the deed of surrender.[9] Stephens was pensioned off with a hundred marks; and some of the monks received various annuities and compensations for their losses. So fell the monastery of Beaulieu, and its stones went to build Henry VIII.'s martello tower at Hurst, and its lead to repair Calshot,[10] to fight against the very Power which had raised it to its glory.

Nothing could be more beautiful than its situation on the banks of the Exe, formed by the tide more into a lake than a river. On every side it was sheltered: on the north by rising ground and the woods of the New Forest, and on the east again by the Forest and more hills, from whence an aqueduct brought down the water for the use of the monks; and on the south and west all was guarded by the river.

To this day the outer walls are in places standing, with the water-gate covered with ivy. And inside is the abbot's house, placed amongst its own grounds, surrounded by elms. Above its doorway is cut a canopied niche, where stood the patron saint, the Virgin, and above runs the string-course, supported by its carved corbel-heads. But the whole building has been unfortunately defaced by a moat and turretted wall, built as a defence by one of the Montagues against French privateers, as also by the modernized windows.

Entering, we come into the guesten-hall, the magna camera arcuata, formerly hung with tapestry, where the minstrels entertained the guests with songs or tales. Like all the other rooms, it has been sadly modernized, though its fine groined roof, springing from four shafts on each side, and a lancet window in the east wall, still remain. Upstairs, too, is left some oak panelling of Henry VIII.'s time, of the linen pattern, but covered over with paint. Eastward, in the meadow adjoining, stands the dormitory, better known in the village, from its former occupants, as Burman's House. Passing through it, we suddenly come upon the green quadrangle once surrounded with cloisters, where the three arches leading into the chapter-house still remain. The black Purbeck marble shafts, and bands, and capitals, have, however, long since become weather-worn and decayed, though the Binstead and Caen stone still stands, here and there covered with ivy, crested with wall-flowers, and white and crimson pinks, and rusted with lichens.

In the chapter-house are strewed the broken pillars which supported the groined roof, and the broken stone-seats which ran round the inside, whilst on the floor lie a stone coffin and gravestones. To the north of it stand the ruins of the sacristy, which had an entrance from the south transept of the church, from which, also, a staircase led to the scriptorium.

Of the cloisters, the north alley is the most perfect, with its seven carols, where the monks sat and talked; whilst above project the corbels which carried the cloister-roof. Here and there, too, as at the two north doors leading into the church, some of the original pavement still remains, and at the south-east corner a staircase led to the lavatory.

The church, however, has long since been destroyed. Nothing, except a portion of the south transept, is left. The foundations, though, can be accurately traced, showing the nave and aisles, and the large circular apse at the east end. Scattered about, too, appear the tesselated floor, bright as on the day it was laid down, and the graves of the abbots, and of Eleanor of Acquitaine, mother of the founder.[11]

Out in the fields beyond stand the ruins of a building, now a mere pinfold for cattle, called by tradition the Monk's Vine-Press, whilst the meadows beyond, lying on the slope of the hill, are still known as "the Vineyards."[12]

But the refectory still remains on the south side of the cloisters, from which a doorway, still ornamented with iron scroll-work, used to lead. Ever since the Reformation it has served as the parish church, differing only in its appearance by its lack of orientation.[13] In 1746 it was repaired, and its original roof lowered, and its fine triplet at the south end spoilt by a buttress, and one of the lancets lighting the wall-passage on the west side also blocked up. Its walls, however, are now covered with common spleenwort, and wall-lettuce, and pellitory, whilst the narrow-leaved rue—the "herb o' grace o' Sundays"—with which the old churchyards used to be sown, shows its pale blue blossoms amongst the gravestones.

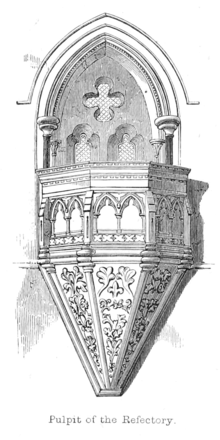

Inside it is still more interesting. Here still stands the lovely stone pulpit, its panels rich with flower-tracery, approached by a wall-passage and open arcade springing from double rows of black Purbeck marble pillars. This was the old rostrum of the monks, where one of the brethren read to the rest at their meals; so that, as St. Augustine says, their mouths should not only taste, but their ears also drink in the Word of God. Here, in this very village church, the old Cistercian monks obeyed the injunction which the Bishop of Hippo gives to the canons of his own order,—"When we enter, let us bare our heads, and going to our seats bend before the cross. Let us not behave idly, lest we give offence to any one. Let not our eyes wander, lest we give occasion for bickering, or quarrelling, or laughing; but fulfilling the saying of the blessed Hugh of Lincoln, 'let us keep our eyes upon the table, our ears with the reader, and our hearts with God.'"[14]

In the churchyard, plainly traceable by the ruined foundations, and mounds, and depressions, are the sites of the lavatory and kitchens, whilst in the fields beyond lie the fish-ponds. Everywhere, in fact, are seen the traces of the monks. Their walks still remain by the side of the Exe, overgrown with oaks, bright in the spring with blue and crimson lungwort, and sweet with violets, such as grew when Anne Beauchamp sought refuge here that dismal Easter day.

Not only do the Abbey grounds,[15] but the whole district, show the size of the monastery. Going out of Beaulieu, upon the road to Bucklershard, we come upon the ox-farm of the monks, still called Bouvery, and still famous for its grazing land. A little further, about the centre of their various farmsteads, at St. Leonard's, better known now as the Abbey Walls, stands part of the large barn, or spicarium, of the monastery, such as still remains in other parts of England—at Cerne Abbey, and Abbotsbury, and Sherborne, and Battle Abbey.[16] A modern barn now stands within it, partly formed by its walls, but its original size is well shown by the lofty eastern gable, locally called the Pinnacle, which, covered with ivy, overhangs the road.

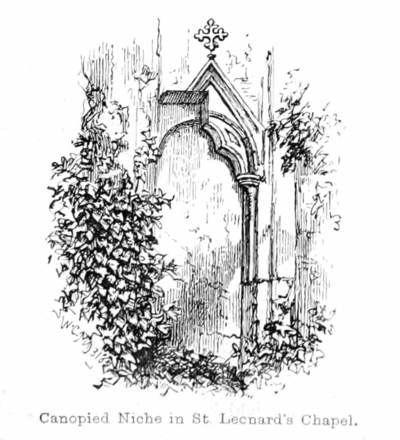

Close to the old farm-house, built from its ruins, stands a small roofless Decorated Chapel. The west window, and the arch of

the west doorway, still remain, and at the same end still project the corbels which supported the gallery. In the east wall are canopied niches, under which stood figures; and on the south the stoup, and the broken conduit where the holy water ran, and two aumbries are still visible, whilst opposite to them, in the present doorway, another aumbrie is inserted with its two grooves for shelves cut in the stone.[17]

Close to St. Leonard's lies also the sheep-farm of the monks, still called Bargery, and still famous for its sheep-land. Nearer Bucklershard is Park Farm, another grange, where fifty years ago stood a chapel, smaller even than the one we have just seen, partly Early-English and Decorated. It was divided into two compartments by a stone screen reaching to a plain roof. The piscina in the south wall was finally used by the ploughmen to mix their wheat with lime, until the whole building was pulled down to enlarge the farm-house from whose south-east end it projected.[18]

At these two granges the brethren worked in summer from chapter till tierce, and from nones till vespers. Here lived the ploughmen and artisans, the millers, and smiths, and carpenters, of the monastery. For them were these chapels built, lest either the weather or the roads might prevent them going to the Abbey Church.[19] Here they all worshipped as one family, the serf no longer a serf, but a freedman, when he entered the service of the abbey.

Farther away to the westward lies Sowley Pond, called in the Abbey Charters Colgrimesmore, and Frieswater, covering some ninety acres, formerly the boundary of the abbey estate, and used by the monks as a preserve for their fish. Here once were iron-works, whose blast-furnaces were heated with wood and charcoal from the Forest. The iron-stone was brought from Hengistbury Head and the Hordle Cliffs, and after being melted was shaped by the tilt-hammers, and finally sent off inland to Reading, or shipped at Pitt's Deep. But like all the other ferraria of Sussex and Hampshire, these too have long since been stopped, driven out of the field by the Staffordshire iron-works. Nothing now remains to tell their former importance but a few mounds and the village Forge-Hammer Inn, and a country proverb, "There will be rain when Sowley hammer is heard," whose meaning is fast being lost.

Returning, however, to Beaulieu, let us once more look at the old abbey and the ruins of the cloisters, and try to imagine for ourselves the time when, secluded from the world, in the midst of the New Forest, the monks from Citeaux prayed and worked, clad in their coarse white woollen robes, and slept, according to their vow, on pallets of straw, giving shelter to the fugitive, and food to the hungry.[20] It is only by seeing some such grey ruins as these, still breathing of a long past religion, placed amongst the solitude of their own green meadows and woods, by the silent lapse of some stream flowing and ebbing with every tide, that we can at all understand the meaning of a life of contemplation, and its true value. Along these cloisters paced the brethren, their eyes bent on the earth, their thoughts on heaven. Here tolled the great abbey-bell, its sound, full of solemn sweetness, borne not only over the lonely Forest, but down the river seaward to the tossing sailor. Here was that comfort, which could never fail, offered to the most desolate, and heaven itself, as a fatherland, to the exile. Here the great gate not only rolled back the noise of the world, but, to show that mercy is ever better than vengeance, stayed the hand of the law, and blunted the sword of the pursuer.

In these days we are surrounded by noise and excitement. Everywhere is haste and its accompanying confusion. It matters not what we do, the fever of competition ever rages. We travel as though we were flying from ourselves. We write the history of things before they are accomplished, and the lives of men before they are dead. Sorely there is some profit to be found in coming to a quiet village like this, if it will only give us some glimpses of a life which stands out in such strange contrast to our own.

Footnotes

edit- ↑ For an account of the barrows on Beaulieu Heath, see ch. xvii.

- ↑ Dugdale's Monasticon Anglicanum. Ed. 1825, vol. v., p. 682. Num. ii. See Chronica de Kirkstall. Brit. Mus. Cott. MSS. Domitian. A. xii., ff. 85, 86. The cause of John's enmity against the Cistercian Order may be gathered from Ralph Coggeshale, Chronicon Anglicanum, as before in Bouquet, Recueil des Historiens des Gaules et de la France, tom, xviii. pp. 90, 91.

- ↑ Carta Fundationis per Regem Johannem, given in Dugdale (Ed. 1825, vol. v. p. 683); and Confirmacio Regis Edwardi tertii super cartas Regis Johannis, Brit. Mus., Bib. Cott. Nero, A. xii., No. v, ff. 8-15, quoted in Warner (South-West Parts of Hampshire, vol. ii., Appendix, pp. 7-14). There are, however, no less than three dates given for its foundation. The Annals of Parcolude, according to Tanner (Notitia Monastica, Ed. Nasmyth, Hampshire, No. vi. foot-note h), say 1201, which is manifestly wrong; whilst John de Oxenedes, better known as St. Benet of Hulme (Chronica, Brit. Mus., Bib. Cott., Nero, D. ii., f. 223 K), with the Chronicon de Hayles and Aberconwey (Brit. Mus., Harl. MS., No. 3725, f. 10), and Matthew Paris, according to Dugdale, say respectively 1204 and 1205, though I have not been able to verify the last reference.

- ↑ Roger of Wendover, English Historical Society. Ed. Coxe, vol. iii. p. 344.

- ↑ See the previous chapter, pp. 57, 58, foot-note.

- ↑ Curiously enough, as Warner remarks (vol. i. 267), Matthew Paris gives two dates for the dedication, the first 1246 (Hist. Angl., tom. i. p. 710, Ed. Wats., London, 1640); and the second (p. 770) 1249; not, however, 1250, as Warner says, and who, followed by all later writers, totally misunderstands the passage, which means that, although the abbot spent so large a sum, yet the King would not remit him the fines he had incurred by trespass in the Forest,—"Nec tamen idcirco aliquatenus pepercit rex, quin maximum censum solveret illi pro transgressione quam dicebatur regi fecisse in occupatione Forestæ."

- ↑ See Matthew Paris, in praise of the Cistercian Order. Same edition as before, tom. i. p. 916.

- ↑ Not Margaret of Anjou, as the common accounts say, who, landing at Weymouth, took refuge at Cerne Abbey. See Historie of the Arrival of Edward IV. in England, pp. 22, 23, printed for the Camden Society, 1838; and Hollinshed's Chronicles, vol. iii. p. 685; and Speed, B. ix. p. 866. Hall, however (The Union of the Families of Lancaster and York, p. 219), with Grafton, in his prose continuation of Hardyng (Ed. Ellis, 1812, p. 457), say it was to Beaulieu that Margaret fled. But they are evidently mistaken, as Speed and Hollinshed, and the explicit and circumstantial narrative of the author of the Historie, show.

- ↑ The following list of books at Beaulieu, quoted, with some omissions, by Warner (vol. i. p. 278) from Leland (Collect. de Rebus Brit., vol. iv. p. 149), taken just before the dissolution, will show what was in those days an average ecclesiastical library:—The Life of Archbishop Anselm, by Edmerus the monk, bound up with the Life of Bishop Wilfrid; Stephanas on Ecclesiasticus; Stephanus on the Book of Kings; Stephanus on the Parables of Solomon; John, Abbot of Ford, on the Canticles; Damascenus on the Acts of Balaam and Josaphat; a small book of Candidas Arrian; a small book of Victorinus, the Rhetorician, against Candidas; three books of Claudian, respecting the Stale of the Soul, to Sidonius Apollinaris; Gislebertus on the Epistles of St. Paul; Prosper on a Life of Contemplation and of Activity.

- ↑ Ellis's Letters, second series, vol. ii. p. 87. For Henry VIII.'s enforcement of Wolsey's levies on Beaulieu, see State Papers, vol. i., part ii., p. 383.

- ↑ A few years ago, when the foundations were being excavated, a female skeleton was found near the high altar, and was supposed, by its position, to have been that of the Queen.

- ↑ Warner (vol. i. 255) mentions that in his time there was still brandy in the steward's cellars made from the vines growing on the spot. Domesday gives several entries of wines (see Ellis's Introduction, vol. i. pp. 116, 117), though none in the Forest district. But the term 'Vineyards' is still frequently found hereabouts as the name of fields generally marked by a southern slope, as at Beckley and Hern, near Christchurch, showing how common formerly was the cultivation of the vine, first introduced into England by the Romans.

- ↑ In Brit. Mus., Harl. MS. 892, f. 40b, is an extract from a most interesting letter written in 1648, describing the state of the refectory, which seems, with the exception of the alterations made in 1746, to have been much the same as at present.

- ↑ Quoted from Dugdale's Monasticon Anglicanum by Warner, vol. i. p. 249.

- ↑ It is pleasant to have to add that the present noble owner, the Duke of Buccleuch, has shown not only good taste and judgment in the restoration of the dormitory and the excavation of the church, but a wise liberality in throwing the grounds open to the public.

- ↑ In Parker's Glossary of Architecture is given a list of some of these old barns. Vol. i. pp. 240, 241.

- ↑ Some curious leaden pipes, soldered only on one side, were dug up close by, which are worth seeing, as they show how late the process of running hollow lead pipes was invented. The earthenware pipes found with them are as good as any which are now made. At Otterwood Farm, on the other side of the Exe, pavement and tiles have also been discovered.

- ↑ The chapel was standing in Warner's time. South-Western Parts of Hampshire, vol. i. pp. 232, 233.

- ↑ In Brit. Mus., Bib. Cott., Nero, A. xii., No. vii. f. 20 a b, is a copy of a Bull from Alexander I., giving permission to all the Cistercian Houses to hold service at their granges.

- ↑ Even Layton saw their kindness, and pleaded for the poor wretches whom they had protected. Letter regarding Beaulieu Sanctuary from Layton to Cromwell, Ellis's Letters, third series, vol. iii. pp. 72, 73.