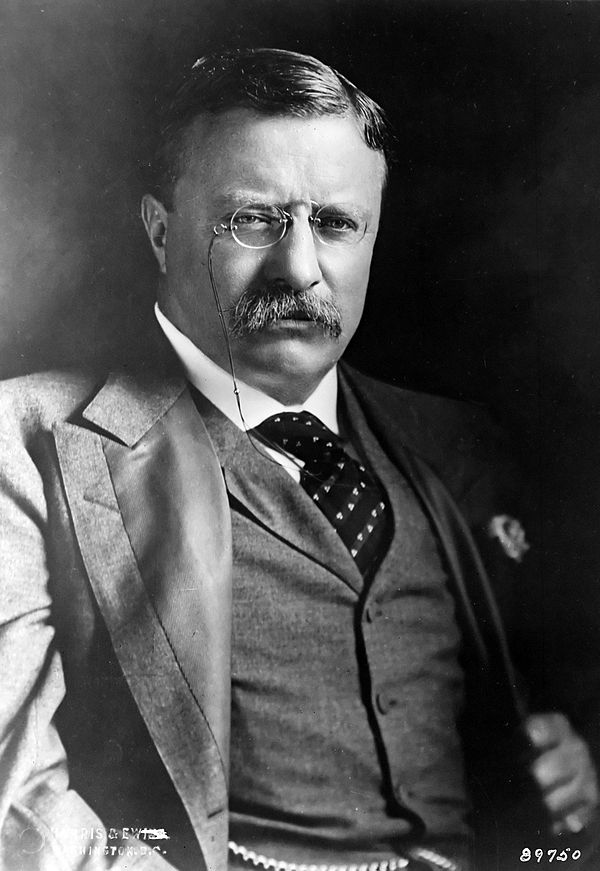

The Presidents of the United States, 1789-1914/Theodore Roosevelt

|

| Copyright by Harris & Ewing, Washington |

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

I

Until the inauguration of Theodore Roosevelt,

forty-seven was the age of our youngest president,

General Grant. With the further exceptions of

Polk, Pierce, Garfield, and Cleveland, no other had

been under fifty. Roosevelt was not quite forty-three.

Of twenty-seven presidents, he was the

fifth whom death, instead of election, placed in the

White House.

Theodore Roosevelt was born October 27, 1858, in his father's house, which was No. 28 East 20th Street, New York city. Like most of his predecessors in office, he comes of a family which has been American since early colonial times. For two hundred and fifty years New York has been the native soil of the Roosevelts. Since they made their beginnings in the colonies, they have been plentifully represented in public life and in good works; and a study of former Roosevelts shows them to have attained distinction as fighters, as writers, in politics, and in philanthropy. It would seem that President Roosevelt drew from all these ancestral sources the qualities that have so forcibly marked his career.

His boyhood was passed chiefly in the city of his birth, and it was here that he received his early schooling. In that day the health of his body seems to have been fragile; the ordinary games of boys were beyond his strength. But it is evident there could have been no weakness in the health of his mind. Perceiving the necessity for a vigorous constitution, he set himself to the getting of one. From this purpose he seems never to have swerved, and by the time he was ready to enter Harvard College he had begun to be robust.

His four years of college life show his character and tendencies as completely as does any period which has followed them. His energies were directed to bodily exercise, to study, and to all the social advantages that Boston afforded him. Although conspicuous in no single athletic sport, he was energetic in a variety, sparring and horsemanship being among them. His knowledge of sparring, besides the general benefit that it was to him, proved at least upon one later occasion in the West of particular service, and enabled him most successfully to surprise a typical saloon bully who had attempted to take liberties with him. As a student, he was as attentive and energetic as in muscular exercise; and here also, though not conspicuous in any one branch, he devoted himself with industry to several, political history being perhaps the chief of these. He read “The Federalist” with especial interest and attention, and his mind evidently turned as by instinct to such questions and problems as our republic has solved already, or has still to solve. During his college course he was an editor of the “Harvard Advocate,” in whose columns he made his first appearances in print. Besides political history, he continued an interest in natural history, which had been begun in those boyhood days when he was in search of health, and studied the birds of his country neighborhood near Oyster Bay. He was graduated in 1880, a student of sufficiently high rank to make him a member of the Phi Beta Kappa society.

Upon leaving college he traveled in Europe, and here also his time may be said to have been divided between study and hard physical exercise. This latter was mainly in Switzerland, where he climbed, among other peaks, the Matterhorn. Upon his return from Europe, where he had been absent for about a year, he studied law for a time in the office of his uncle, Robert B. Roosevelt. This was in the year 1881, which saw him attend his first primary and also write his first book, “A History of the War of 1812.” The book was the beginning of an eminent literary career, as the primary was the beginning of a political career still more eminent.

It is said that applause was the only result of Roosevelt's first political speech, somewhat to his surprise. His entire inexperience led him to mistake the clapping of hands for a conversion of morals; but the approval was only a good-natured and half-ironic encouragement to a young beginner who seemed in his innocence to be advocating reform, and it went no further — the morals and the votes remained as if Mr. Roosevelt had not existed. Nevertheless, he had made an impression. Very soon after this first attempt there was a revolt in his district, the Twenty-first. Dissatisfaction with some of the leaders led to a split, and the party in revolt chose Roosevelt as their candidate to the assembly.

The close of 1881 saw Theodore Roosevelt a member of the New York Assembly from the Twenty-first district, and identified so closely with the cause of decent politics, and so plainly a type of clean patriot, as to win from his opponents, the routine politicians, the men with no creed save their pocket, the name of Silk Stockings.

With such a name the politicians of the pocket expected that the young reformer's career would be short-lived. To their somewhat limited vision he had everything against him. He was highly educated; he came of a line of forefathers who had been well-to-do, and also public spirited for the sake of the common welfare instead of for their own; and he belonged to what is called Society. These were heavy odds, in their opinion, against a man being useful to his country and harmful to themselves, and so they dismissed him with the term Silk Stocking. But they reckoned without the American people, who, when it comes to the point, are fond of honesty. The young reformer had a strong equipment. He had made himself physically vigorous. His determination was implacable. He had studied government with all the earnestness of his character. He had visited foreign places and returned possessing a knowledge of other countries, and hence, through power to make practical comparisons, the key to a proper understanding of his own. And to this very rich equipment he added the true spirit of democracy, recognizing merit wherever he met it. Such a man was Theodore Roosevelt when he went to Albany at the age of twenty-three, the youngest assemblyman in New York. To the surprise and distaste of the purse politicians he was twice re-elected to the legislature, serving the terms of 1882, 1883, and 1884, and coming to be the leader of the minority.

One of the chief measures for cleanliness in which he played a leading part was abolishing the fees in the office of the register and county clerk. Through the investigation which he then originated, it came to light that the county clerk took $82,000 a year in fees, and that the sheriff pocketed about $100,000. These traditional thefts were ended through Mr. Roosevelt's agency. Through him was abolished the power of the New York board of aldermen to confirm or reject the mayor's appointments. He also secured the passage of the civil-service reform law of 1884. Besides these achievements he put through the anti-tenement cigar-factory bill. A police investigation would have been instituted under his inspiration had he longer remained an assemblyman. Such an activity as this naturally got him many enemies among the purse politicians; nevertheless, in 1884, he had made such strong friends that he was sent to the republican national convention. It was as a supporter of Mr. Edmunds in opposition to Mr. Blaine that he went to Chicago.

In this same year of 1884 he joined the National Guard of New York, beginning as lieutenant in the Eighth regiment, and ending as captain. His service in the militia somewhat exceeded four years in duration, and was most useful to him as a preparation for his more important activity in the Spanish war of 1898.

Also in the year of 1884 came a crisis in Mr. Roosevelt's career. Upon Mr. Blaine's becoming the republican candidate for president, those friends of Mr. Roosevelt whose faith in him had been based upon his political independence were turned against him because of his adherence to his party's choice. Although he has been known to say that he does not count party allegiance among the Ten Commandments, it is nevertheless his belief that breaking with one's party should be a step of the last resort; that in nine cases out of ten more effective good can be rendered by remaining with one's party even while not in total agreement with it. Mr. Roosevelt declined to join that movement of republicans which elected Mr. Cleveland. The enmity from former friends which he incurred by this has been as bitter, and sometimes almost as harmful, as the enmity which he has always had from purse politicians.

Before this time Roosevelt had traveled in the West. He now returned there and became a ranchman at Medora on the Little Missouri. Of his experiences in the Rocky Mountains much has been said; it is enough to say here that they made a picturesque episode in Roosevelt's life, added to his knowledge and his love of the American people and to their knowledge and love of him. From these years he also drew the inspiration and the material for his books about western life, which were the first complete picture of this life that had appeared in literature. Mr. Roosevelt returned East in 1886.

He was now again called into the world of politics, and became a candidate for mayor of New York. He had accepted an independent nomination, and upon this was indorsed by the republican party. He was defeated by Mr. Hewitt, but he polled relatively a larger vote than any republican candidate had done up to that time. As usual, no activities, whether those of a wilderness hunter or those of a republican candidate for office, caused his pen to be idle. In this year he wrote his “Life of Thomas H. Benton,” and in the following year his “Life of Gouverneur Morris.” As to his literary style, it should perhaps be remarked that the themes which he has usually chosen do not call for all the resources of expression that he has at command. Force, simplicity, clearness, and, when necessary, incisive satire, are the qualities which his historic, political, and critical writings reveal; but besides these characteristics he can use, when he needs it, considerable poetic subtlety. No man who had not in him somewhere a strain of the artist could have made the remark which he did about the Western Bad Lands, that they resembled in appearance the sound of the language used by Edgar Allan Poe.

After his contest for the mayoralty of New York, though he was to be nine years in the public service, no elective office was offered him until he ran for governor of the state. In 1889 he was appointed by President Harrison a member of the United States civil service commission.

As his life had been at Albany, so it now was in Washington — a struggle for honesty against the purse politicians. His methods here were the same as those which had surprised and dismayed the legislatures of New York. They were (as they have always been) characterized by a directness and candor which on the face of them appeared to be based upon inexperience or ignorance, but which were in reality based upon extremely shrewd and adroit observation. Mr. Roosevelt added twenty thousand places to the scope of the reform law, and so admirable was his work altogether that President Harrison has said of it: “If he had no other record than his service as an employee of the civil service commission, he would be deserving of the nation's gratitude and confidence.” Mr. Cleveland, upon succeeding Mr. Harrison as president, retained Roosevelt, and thus his work continued for two years more, until May 1, 1895, when he resigned to become president of the Police board of New York city.

Besides his other labors, while in Washington, he had begun what he considers his most important literary work, “The Winning of the West,” and had also written many fugitive articles upon the subjects of natural history and politics.

For nearly two years he was president of the Police board of New York city, where, as usual, he set himself to the cleaning of the corruption and the blackmail with which he found the entire department rotten. His measures produced the natural outcry of rage from the politicians with whose pockets he began materially to interfere, and his enforcement of the excise law was for a while unfavorably looked upon by many of his friends. But he was of President Grant's opinion, that if you desire the repealing of a bad law you had better enforce it; and enforce the excise law he did. But his new ways, which so disgusted the politicians, delighted the policemen, who soon recognized in him their best friend. His midnight visits to all sorts of streets and haunts in a sort of incognito, in order that he might be able to see with his own eyes how his orders were being carried out, came to be liked more than they were feared; while his instant recognition and rewarding of any bravery shown by a policeman while in the course of duty still more endeared him to the force. It is recorded that until Roosevelt's time if any policeman happened to ruin his clothes through the process of making an arrest the price of a new suit came out of his own pocket. Roosevelt remedied this in justice, and a new suit was furnished at the public expense.

On April 6, 1897, he was again called to

Washington, this time to serve as assistant secretary of

the navy. In this office he spent just one year and

one month. To his immense energy and intelligent

knowledge of what was required to make a navy

efficient in time of war are largely due the

successes which attended our captains in 1898. In that

year, and on May 6, Theodore Roosevelt resigned

his position as assistant secretary of the navy.

War had been declared against Spain, and for

every reason he was moved to take a personal part

in the contest. He felt that any man who had

talked so much and written so much about the duty

and the necessity of defending one's country should

make good his words by deeds.

His apprenticeship in the New York militia now served him in good stead. With Leonard Wood as colonel and himself as lieutenant-colonel the first cavalry regiment of United States volunteers was organized. Owing partly to the unusual and picturesque personnel of the enlisted men, comprising young fellows from Newport and cowboys from the West, united in a brotherhood of patriotism and adventure, each discovering that one was as good as the other, and also partly owing to the personality and the capabilities of Roosevelt and Wood, this regiment became undoubtedly one of the popular heroes of the Spanish war. Even the name of Dewey will hardly live more upon the lips and in the hearts of the people than the name of the Rough Riders. Their part at San Juan was an unusually brilliant one for a volunteer regiment in its first campaign; and when the war was over Mr. Roosevelt found himself a national figure, and also the center of popular enthusiasm in his own state. It was not possible for his political enemies to stand up against the fervor which the name of Roosevelt instantly aroused upon any occasion; and, little to the relish of these politicians, they were obliged to accept him as the candidate of the republican party for governor of New York. In the fall of 1898, at the age of thirty-nine, Theodore Roosevelt was chosen to this office. It is singular to contemplate his two kinds of enemies. These were, on the one hand, the rabble of dishonesty and ring politics that he had been successfully fighting and thwarting since the beginning of his career, and, on the other, certain supercivilized citizens of Boston and New York, whose inflamed consciences had developed into tumors. The “New York Journal” and the “Evening Post” have at various times denounced Mr. Roosevelt with equal bitterness, concealing as much as possible his successes and exaggerating as much as possible his failures.

No one knew better than the governor that his

work in the cause of honesty in New York was

scarcely begun in the spring of 1900. Some things

he had certainly accomplished, and in some efforts

he had distinctly failed. These events draw too

near the present time to demand recapitulation.

But it must be stated by way of reminder how

greatly he deprecated the notion of being taken

from his work in New York for any reason whatever.

Events, however, are stronger than any

man's opinion; and in looking back upon the

popular

determination that Theodore Roosevelt should

be the next vice-president, the religious mind is

tempted to see in this the hand of a foreseeing and

guiding Providence. The attention of our country

has too often been careless in the choice of a

vice-president. Totally against his will, therefore, but

entirely beyond his control, the sweep of his

popularity brought him the republican nomination.

On March 4, 1901, Theodore Roosevelt became Vice-President of the United States. He held this office six months and ten days. On Friday, September 6, 1901, President McKinley was shot at Buffalo; he died on Saturday, the 14th of the same month. This tragedy brought upon Roosevelt suddenly the greatest responsibilities which a man's shoulders can be called upon to bear. At Buffalo, upon that day, at the residence of Mr. Wilcox, Elihu Root, the secretary of war, requested, for reasons of weight connected with the administration of the government, that Mr. Roosevelt take the oath as president at once. Mr. Roosevelt replied: “I shall take the oath of office in obedience to your request, sir, and in doing so it shall be my aim to continue absolutely unbroken the policy of President McKinley, which has given peace, prosperity, and honor to our beloved country.” These words were not long in spreading far and wide, and their effect produced at once a confidence as far and wide. In the presence of all the cabinet, save the secretary of state and the secretary of the navy, the oath was taken, Judge Hazel of the United States District Court administering it. The new president hereupon said: “In order to help me keep the promise I have taken, I would ask all the cabinet to retain their positions at least for some months to come. I shall rely upon you, gentle men, upon your loyalty and fidelity to help me.” The sentiment of these words also produced a happy effect upon the nation; and a few days later, in Washington, President Roosevelt made clear his desire that no changes should occur in the cabinet. The members of it were John Hay, secretary of state; Lyman J. Gage, secretary of the treasury; Elihu Root, secretary of war; John D. Long, secretary of the navy; Ethan A. Hitchcock, secretary of the interior; James Wilson, secretary of agriculture; Philander C. Knox, attorney-general; Charles Emory Smith, postmaster-general. Upon the same Saturday that he took the oath, President Roosevelt issued the following:

“A terrible bereavement has befallen our people.

“The President of the United States has been struck down; a crime committed not only against the chief magistrate but against every law-abiding and liberty-loving citizen.

“President McKinley crowned a life of largest love for his fellow-men, of most earnest endeavor for their welfare, by a death of Christian fortitude; and both the way in which he lived his life and the way in which, in the supreme hour of trial, he met his death will remain forever a precious heritage of our people. It is meet that we, as a nation, express our abiding love and reverence for his life, our deep sorrow for his untimely death.

“Now, therefore, I, Theodore Roosevelt, President of the United States of America, do appoint Thursday next, September 19, the day in which the body of the dead president will be laid in its last earthly resting-place, as a day of mourning and prayer throughout the United States. I earnestly recommend all the people to assemble on that day in their respective places of divine worship, there to bow down in submission to the will of Almighty God, and to pay out of full hearts their homage of love and reverence to the great and good president, whose death has smitten the nation with bitter grief.”

The acts of President Roosevelt since the date

of his oath belong with his acts before his last

exalted office came to him. The best comment

upon them is the confidence in his administration

already shown throughout the country. Whatever

displeasure political circles may have taken in

learning Theodore Roosevelt's determination to

exclude political influence from the army, the navy,

and the colonies, must resemble the displeasure that

political circles have invariably taken at every step

in his career at learning that he proposed, so far

as lay within the scope of his power, to see that

merit, and merit only, was rewarded, and that

honesty, and honesty only, was practised. His

intentions regarding rural free delivery service in

the post-office department correspond with his

well-known views as to civil service reform.

It may be said that his most important acts have not been those to create the greatest comment. One of his least important acts, namely, inviting as a guest to his table a distinguished and honorable member of the colored race, occasioned an outburst of temper from southern newspapers the folly of which reaches such dimensions as to be historical.

His first annual message to Congress, December 3, 1901, was, as could be expected, entirely like himself and wholly unlike most of the preceding documents of this class. Abstract sentiments were few; concrete convictions were many and unequivocally expressed. Its length was immediately forgotten in its interest. Its style was of a very close texture; it was the number and importance of its topics that made it long. Among the many vital themes for legislative attention, such as anarchy, the so-called trusts, the army, the navy, the tariff, and civil-service reform — to mention no more — there was vagueness in only one, namely, the question of ship subsidy. Perhaps no human mind could achieve so much expression of opinion about existing conditions and future policy without some slight dislocation of logic somewhere. In speaking of the Philippines, the message says: “What has taken us thirty generations to achieve we can not expect to see another race accomplish out of hand.” This is surely true. But in speaking of the Indian tribes, the message says: “The Indian should be treated as an individual, like the white man.” Placed next to each other, these two statements contain elements of humor; perhaps had they been called to his attention, Mr. Roosevelt would have expressed them differently.

To describe Theodore Roosevelt as a man of action is true, but is not the whole truth; to describe him as a man of letters is equally true, but is not the whole truth. It is not possible for contemporary judgment adequately to estimate him; to esteem him is easy indeed. It should not go unremarked that he stood on September 14 more unshackled by prejudice than has generally been possible for one in his position. For him the way was unimpeded by extorted promises, and lay clear to work out his duties and his aspirations. It was a day to be full of hope.

The chief accomplishments of what Mr. Roosevelt preferred to call his first administration, instead of calling it the unexpired term of his predecessor, are at present, in the general estimate, outweighed by certain steps more peculiarly and individually his own; and it is likely they will be thus outweighed in the future also; for the accomplishments ended some uncertainties, whereas the steps began some uncertainties. Among the accomplishments should be named the final settlement of the troubles concerning the Alaskan boundary, an important controversy to see satisfactorily terminated. The establishing of the Cuban “reciprocity” is another, not, perhaps, of equal, but of considerable dimensions. The Panama canal question is a third, and it would be difficult to overestimate the value of this. The circumstances under which it was achieved, the recognition, on the part of the United States, of the Panama government as an independent one, brought, not surprisingly, criticism from certain quarters. This place is not the place to answer, but merely to record, such criticism; but it may be said that much lay beneath the surface at that moment which has at no moment since come to public light, and which, if it should ever come, would go far toward changing for any adverse (and honest) critics the unfavorable aspect of the incident; nor does the fact that we had strength upon our side while there was weakness on the other, of itself constitute wrong on our part, as some of the adverse critics have eccentrically elected to assume.

The steps taken by Mr. Roosevelt during his first administration may be counted, for significance, as two: the suit he caused to be brought against that combination of railroad interests known as the Northern Securities, and the commission which he occasioned to be appointed to hear and judge the merits of the coal strike in Pennsylvania. As has already been remarked, these proceedings are more likely to be identified, in the general mind of the future, with Mr. Roosevelt's name, than any of the above mentioned “accomplishments” of his first administration, not excepting the incalculably important Panama incident. Both steps were, at bottom, outcomes of the same vigilance; Mr. Roosevelt is more avowedly and keenly alive than any other patriot in public life to the sinister menace to the stability of our government which lies in combinations, whether they be combinations of “labor” or of “capital.” It is too soon to say what good or what harm these steps have done; but to any American mind (save the mind of an American corporation) it is becoming clear as day that if the corporations pursue and complete their growing control of legislatures, our Republic will change to a syndicate and self-government will explode. For our increasing and wholesome anxiety about this, Mr. Roosevelt is to be honored, whatever imperfections may be found in his corrective machinery so far as it has gone. An equally great, if not greater, service has been rendered to the whole country by Mr. Roosevelt's “Strike Commission,” which not even his friends have had the wit to point out. His apparent siding with “labor” on that occasion led “labor” to commit so many arrogant outrages that the scales fell from the hitherto blind and sentimental public eye, and it was seen that “labor” could become just as dangerous a public enemy as could “capital.” At all events, to sum up, Mr. Roosevelt was in November, 1904, elected president by the largest majority which the history of our nation records; upon which he announced that he considered this his second term.

II

The foregoing was written and published in

1905, and such few opinions as were therein

expressed may stand as then set down — even though

the eight momentous years which have followed

since show that if the public eye saw “labor” in its

true light for a day, the public mind forgot it the

next day, and has remained on the whole as

confused, weak and sentimental as it was before: the

American people seldom remembers anything over

night, and this shortness of memory is a hindrance

to any enlightened public opinion almost as grave

as if our ninety million citizens were born

half-witted. From time to time the insolences, the

destructions and the murders inspired by “labor,”

called forth from Mr. Roosevelt words of the

plainest import — as plain as those which he used

about the tyrannies of “capital”: as when, for

instance, the book-binders union undertook to

order the United States to dismiss from its

employment a man named Miller; as when upon

another occasion he uttered the sharp homely phrase

that “the door of the White House swings open for

the poor just as easily as for the rich, and not a

bit easier”; as when in April, 1907, he coupled the

miscreants of “capital” and “labor” together,

denouncing a certain railroad magnate, with Moyer,

Haywood, Pettibone and other leaders of the

Western Federation of Miners, as “undesirable

citizens”; or as when, some time after his presidency,

in an editorial entitled “Murder is Murder,”

he gave its true character to the assassination of

some twenty men at work in the Times building at

Los Angeles. But for the unexpected confession

of the “laboring” men responsible for this crime,

Justice would undoubtedly have been cheated as

completely as it was in the case of the murder of the

governor of Idaho some years earlier.

Rich and poor become dangerous alike whenever they are able to defy the law (as the rich attempted in the Northern Securities) or to make the law not apply to themselves (as in the exemption of labor unions from the operation of the Sherman anti-trust law — the very same which the rich finally had to obey in the Northern Securities case); it is neither riches nor poverty, but unchecked power, which constitutes the evil and the menace to the State. If analysis of Mr. Roosevelt's enemies be made to-day, these will be found to fall into two chief groups, apparently contradictory; one of money and one of labor, one whose flag may be symbolized by the tape that flows from the stock-broker's “ticker,” and one that waves the red flag of general destruction. But these two are not really contradictory. In their excess they are identical. It is at their excess that Mr. Roosevelt struck. By all these excessives is he hated, by the Harrimans who would be above the law, by the Haywoods who would destroy the law.

Certain recurrent features necessarily mark all administrations, certain similar laws and treaties, which continue to be made because they continue in the nature of things to be required; an account of these would hardly distinguish one president from another. Apart from the foreign treaties ratified during Mr. Roosevelt's second term, significant chiefly in the number of them which provide for arbitration and in the fact that they are so numerous because our points of contact with the rest of the world have increased so rapidly since the Spanish War of 1898 — apart from these, Mr. Roosevelt's second term is marked strongly by three main trends of policy:

He did not wish corporations and financiers to be hobbled, but to be properly harnessed.

He did not wish the laboring man to be a pampered pet, but to be treated as a human being by those who employed him.

He did not wish our waterways and other natural resources (including children) to be disused or misused, but to be cherished and developed for the benefit of the present and the future.

If to these three leading subjects of concern to Mr. Roosevelt, be added the Panama Canal, our relations with South America, and the Army and Navy, most of what was important during his second Administration will be included and classified.

His cabinet, which underwent many changes during the four years, stood thus on March 6, 1905: Secretary of State, John Hay; Secretary of the Treasury, Leslie M. Shaw; Secretary of War, William H. Taft; Attorney-General, William H. Moody; Postmaster-General, George B. Cortelyou; Secretary of the Navy, Paul Morton; Secretary of the Interior, Ethan Allen Hitchcock; Secretary of Agriculture, James Wilson; Secretary of Commerce and Labor, Victor H. Metcalf. Charles W. Fairbanks was Vice-President.

The first change occurred in four months, when Charles J. Bonaparte succeeded Paul Morton as Secretary of the Navy.

No fair account of Mr. Roosevelt's character and public services could fail to be a eulogy such as but two out of his twenty-four predecessors have deserved. Washington and Lincoln are benefactors with whom he is to be classed without being compared. But no fair account of Mr. Roosevelt should fail to allude to some of those public mistakes into which impulse has led him more than once.

Paul Morton was a personal friend. Mr. Roosevelt had seen something of him while on a western journey, and knew him to be endowed with good business powers. Needing a capable Secretary of the Navy, he invited him to take this portfolio; and no doubt Mr. Morton could have made an admirable Secretary. But how should a man directly involved in railroad transactions, to prohibit which Mr. Roosevelt was at that moment doing his utmost to have special laws enacted, be with any propriety a member of the cabinet? Unfavorable comment was here justified, and thus the change was made. This sort of mistake, sometimes grave, sometimes not important, has always been forgiven by the people, because they know Mr. Roosevelt. A sometimes misleading enthusiasm about friends, an occasional failure to judge the character of a man or the propriety of an act, do not impair the popular conviction that at bottom Mr. Roosevelt is generally right. There was bewilderment in 1910 when he spoke in Boston in favor of Senator Lodge, whose politics were utterly at variance with his own; but even this piece of perfect inconsistency was soon understood and laid to the door of old friendship, where it belonged.

A still more important change in the cabinet was when Elihu Root succeeded John Hay as Secretary of State, July 20, 1905. Throughout Mr. Roosevelt's second term, Mr. Root rendered services to the country so sound and brilliant that the President repeatedly declared his Secretary to be the greatest statesman living of whom he had any knowledge. Leaving the service of corporations quite opposed to Mr. Roosevelt's policies, Mr. Root renounced a legal income many times larger than his salary, and, steering an entirely new course, dedicated his remarkable powers to the good of his country during nearly four years. But, before touching upon the achievements which so distinguished him, some other matters must receive brief notice.

During this first summer of the second term, in response to Mr. Roosevelt's invitation and offer of his services, the envoys of Russia and Japan met at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to conclude peace between their countries. Though diplomatic intrigue of foreign governments somewhat impaired this tribute to the United States and its President, the fact remains that this was the first time in our history that we took any such place or played any such part in the concert of nations. Such recognition was very largely due to the personal weight of Mr. Roosevelt. In consequence of his successful intercession he was in 1906 awarded the Nobel prize. With the sum thus received, forty thousand dollars, he endowed the Foundation for the promotion of Industrial Peace. A year later, March 2, 1907, an act was approved providing that the Chief Justice of the United States, the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Commerce and Labor, and their successors in office, together with a representative of labor and a representative of capital, and two persons to represent the general public to be appointed by the President, should be trustees of this Foundation, to hold the money and any other sums given for its purpose, namely, to obtain a better understanding between employers and employees.

Certain complications in the Moroccan coast were the next occasion to bring the United States into conference with foreign powers at Algeciras. This led to a treaty in April, 1906, ratified by the Senate in December, and proclaimed in January, 1907, signed by representatives of twelve powers, providing for the governing, policing and financing of Morocco. Numerous international negotiations were ratified at this time: a supplementary extradition treaty with Great Britain, December 13, 1905; another with Japan, June 22, 1906; a copyright convention with Japan, February 28, 1906; and treaties upon various subjects with Roumania, San Marino, and Mexico. A convention with Great Britain providing for the survey of the Alaskan Canadian Boundary, April 26, 1906, was followed during the next few years by various understandings as to Canada, Alaska, and also the Newfoundland Fisheries — a long vexed question; the Senate early in 1909 ratified an agreement to submit this to The Hague Tribunal. At The Hague, by a treaty signed October 18, 1907, by representatives of practically all civilized nations, and ratified by the Senate early in the following April, a Permanent Court of Arbitration to sit at The Hague was established. Nine treaties regarding the customs and practices of war, signed at The Hague, were ratified by the Senate in 1908. Arbitration treaties with twelve nations — France, Switzerland, Italy, Mexico, Norway, Portugal, Great Britain, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, Japan and Denmark — were ratified during the first half of 1908, as well as naturalization and extradition treaties with several countries, all of them Latin.

This brings us to Mr. Root and South America, with which portion of the Western Hemisphere our dealings have been marked from the beginning with crudeness and stupidity. Our bad manners toward neighbors are an English inheritance which we have considerably augmented. As a very natural consequence, our neighbors both to the north and south do not like us. When the Monroe Doctrine is considered, and our need of adjacent friends instead of enemies in case this doctrine should be forcibly disputed, a century of rudeness on our part does not help our already slender reputation for urbane statesmanship.

Some perception of the need to redeem ourselves had dawned upon preceding administrations. James G. Elaine, when Secretary of State, had presided over the first Pan-American Congress, held in Washington, in October, 1889. A second was called at Mexico twelve years later by Mr. McKinley, who was sensitive to the commercial disadvantages which our incivilities to our southern neighbors had brought upon us. The Third Pan-American Congress was in session at Rio de Janeiro from July 21 to August 26, 1906, and Mr. Root addressed the conference, not as a delegate, but as Secretary of State. Questions of naturalization were considered, but chiefly a plan of uniformity through laws relating to patents, copyrights, and trade-marks; chiefest of all, however, was the subject of arbitration, as it was also in the succeeding conference, held at Buenos Ayres in July and August four years later. Mr. Roosevelt's message to congress of December, 1905, had laid much stress upon the importance of arbitration as making for international peace, and Mr. Root's journey to South America six months later was undertaken with this object. His intellect, his skill and his address brought about the happiest results. It is too often our uncouth habit to commit our international affairs to hands partially or wholly unversed in the usages of civilization. But even the most well-meaning bull can accomplish but little good in a china shop, and diplomacy is a china shop, if ever there was one. Mr. Root “knew how to behave,” if the phrase may be permitted, and he is a proof that our Democracy can produce, even if it be seldom willing to use, men whose training is equal to their intelligence. He was chosen honorary president of the conference of Rio de Janeiro. Later he visited Buenos Ayres, Santiago de Chile, Lima, and was guest of the Mexican Government at Mexico in September of the following year. Some of the results of these journeys were: the extension of the treaty of Mexico (January 30, 1902) regarding the arbitration of pecuniary claims, signed at Rio de Janeiro August 13, 1906, by representatives of the United States, Ecuador, Paraguay, Bolivia, Colombia, Honduras, Panama, Cuba, San Domingo, Peru, Salvador, Costa Rica, Mexico, Guatemala, Uruguay, Argentine, Nicaragua, Brazil and Chile. The work of the Bureau of American Republics was also greatly enlarged. In January, 1907, John Barrett was appointed its director. A year earlier Andrew Carnegie had given seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars for a building for this bureau, and an appropriation of two hundred thousand toward the purchase of a site had been made. To this some of the other republics also contributed. Later in 1907 Mr. Root acted as temporary chairman of a convention of five Central American States, assembled in Washington at the invitation of Mr. Roosevelt and President Diaz to prepare treaties of peace and arbitration in consequence of hostilities between Honduras and Nicaragua. The slippery conduct of Colombia in regard to the project of the Panama Canal had driven Mr. Roosevelt during his first administration to “take Panama,” as he phrased it some ten years later in a speech delivered in Philadelphia. The civilized world rejoices at this summary sweeping away of the intrigues which barred this great avenue of commerce; Mr. Roosevelt's enemies (both tropical and indigenous) have equally rejoiced to obscure and ignore the fact that he acted entirely within the scope of the Treaty of New Granada. Had Mr. Roosevelt waited any longer for Colombia, the canal would be waiting still. You could as easily pin Colombia to any position, said Mr. Roosevelt, as you could “nail a piece of currant jelly to the wall.”

After a month's conference in Washington in 1907, six treaties were drawn, in addition to an agreement being made for the establishment of a permanent international court, to be termed the Central American Court of Justice. Early in 1908 a convention signed August 23, 1906, in Rio de Janeiro was ratified by the Senate, providing for the establishment of an international commission of jurists to prepare draft codes of private and public international law regulating the relations between the nations of America. This was followed in June of the same year by a formal opening of a joint tribunal of arbitration which adjusted a dispute between Honduras, Guatemala and Salvador. The Sixtieth Congress (first session December 3, 1907, to May 30, 1908) had created already two new diplomatic posts, Honduras and Nicaragua, giving us a minister at each of the five Central American Republics. These provisions against disorders did not end disorders forever, but they furnished better means for dealing with them. The first arbitration treaty between the United States and South America was that signed by Secretary Root and Mr. Pardo, the Peruvian Minister. We cannot here dwell upon the various troubles between ourselves and the South American countries or the troubles between themselves; but the adventurer Castro, of Venezuela, should not be wholly passed over. During the ferments in his unrestful country he had boiled up from the bottom, without antecedents, education or principle, but with some sort of savage force, owing to which he had come to the top, stayed on top, and finally usurped the dictatorship. He soon laid his hands upon some valuable asphalt properties which had been conceded with due legality to Americans. He declined to arbitrate the matter (July, 1907) and the High Federal Court of Venezuela, from which there was no appeal, subsequently annulled the concessions in obedience to his orders. On Castro's continued refusal to arbitrate, relations between the United States and Venezuela were broken off in June, 1908. Castro had that aversion to paying his debts which is common to adventurers, and in August the Netherlands prepared to take active measures in regard to some claims of theirs. This brought some private understanding between them and ourselves. A revolution in Venezuela, bloodless on this occasion, led to Castro's taking himself off to Europe; and we sent a special commissioner together with a fleet to Venezuela. That the various adjustments then made satisfactorily will be permanent is fervently to be hoped. Our understanding with the Netherlands in 1908 was the logical sequel to a convention between ourselves and the Dominican Republic of February 25, 1907, ratified in June and proclaimed in July. There had been trouble in the collection and application of the customs revenues of San Domingo; and to obviate foreign interference for the payment of claims, the United States had undertaken in 1905 to administer the troubled finances of the country. Pending action by congress, a temporary arrangement was made in 1906, a special Commissioner was appointed, and the treaty of 1907 followed his report. Our Monroe Doctrine laid upon us this odd office of collecting and paying the debts of one South American nation, and it is to be hoped our responsibilities of this kind will not increase; in our foreign affairs there is no piece of equilibrium more unstable than the possible consequences of the Monroe Doctrine.

Trouble in Cuba had compelled Mr. Taft, Secretary of War, to go there on September 14, 1906, proclaim himself provisional governor and establish military rule. He was succeeded by Charles E. Magoon, an admirable, competent, much slandered and little recognized official. In his message to congress of December 3, Mr. Roosevelt cautioned Cuba that, “if the elections became a farce, and if the insurrectionary habit becomes confirmed on the Island, it is out of the question that the Island should remain independent.” This message also referred to another piece of unstable equilibrium in our foreign relations — namely, the issue between the United States Government and the State of California as regards Japan.

The question is thirty years old. California has objected to the coming of Asiatics to settle. Her objection has not always been based on the same grounds; Oriental immorality and racial incompatibility have been alleged; but a famous line in a famous poem, “We are ruined by Chinese cheap labor” probably hits the truth. However they may differ from us in morals or in other traits, the Asiatics are more thrifty, more industrious, more efficient as laborers, and can live on less than Americans. One Chinese or Japanese servant in a house does the work of two or three servants of other nationalities, and it is the same with out-door labor. This has been true ever since George Washington characterized the American farmer as the most shiftless and wasteful that he knew. But California's contention that her state is for her own people and not for aliens, be they better or worse than native citizens, is not easily answered. The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1881. No other Asiatics were then considered. This is not the place to narrate the long and complicated story of the agitation, or the hand which the labor unions took in the matter in 1906, when the Mayor of San Francisco excluded Japanese children from the public schools. The labor unions have become a worse enemy to California than the Southern Pacific railroad, and the advantages which they took over a prostrate community at the time of the earthquake in 1906 are almost unparalleled in bestial greed. But the only point which can be touched on here is, that in his message of December 3, 1906, to the 59th Congress, Mr. Roosevelt declared that the Japanese in San Francisco should be treated justly and their rights must be enforced. Much excitement was caused in California by this declaration, and various inquiries, law-suits and investigations followed, bringing out, among other facts, that the school question was of far less importance than had been represented — only ninety-three Japanese scholars being in the schools — and that there had been attacks and boycotts of Japanese restaurants and citizens. Our treaty of 1893 with Japan had assured that nation a favorable treatment for its citizens during their stay in this country. Some interviews between authorities from California and the White House followed, some adjustments were made, and whatever irritation the newspapers of Japan and America had fomented was allayed by Mr. Taft when he visited Japan on his important journey round the world in 1907. In November of that year, Baron Hayashi, Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs, made an official statement for publication on the relations of the two countries, for the purpose of checking misrepresentations calculated to mislead the public. The matter was then for the time quieted; but it is by no means yet settled, as recent occurrences have plainly shown. With us a divided opinion about California's attitude prevails. But that any State of the Union can at any moment disregard and impair the utility of a treaty made with a foreign nation by the United States is something about which opinion cannot be divided.

After his private audience at Tokio with the Emperor of Japan, October 2, 1907, when the California difficulty was smoothed down, Mr. Taft attended the first Philippine Congress, which he opened on October 16. On December 23 he delivered at St. Petersburg an address on the subject of world peace, and on the 20th he finished at New York his journey round the world.

Four days previous to his return, the Atlantic Fleet left Hampton Roads. Its journey was also to be round the world. The President reviewed it. His enemies were greatly shocked at this cruise. The fleet reached San Francisco by way of the Straits of Magellan; sailed on to Hawaii, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, China and Manila; thence home by way of India, the Suez Canal, the Mediterranean ports and Gibraltar. The voyage took about a year and two months. Mr. Roosevelt's enemies have always been particularly shocked at anything suggested by him that was particularly useful. This cruise was of inestimable value in training for the fleet and in aiding to establish satisfactory relations with other countries. Three memorable journeys, Mr. Root's to South America, Mr. Taft's and the fleet's round the world, are to be counted as the most signally excellent steps of his administration apart from certain measures economic and humane carried through by his direction and influence. Mention should be made of a sanitary convention with eleven South American countries signed October 14, 1905, ratified May 29, 1906, and a more important arrangement of similar kind, concluded at Rome, December 9, 1907, and ratified February 10, 1908, with ten European nations and Egypt for the establishment and regulation of the international office of public health.

During the disturbances in South America and elsewhere, we had others at home, to some few of which allusion should be made. From March to July, 1906, there was a strike of bituminous coal miners sufficiently serious to call for the same sort of intervention from Mr. Roosevelt as the anthracite coal strike had occasioned during his first term. Of this earlier intervention and its unprecedented character, the heads of the coal railroad could not think sufficiently ill; therefore it is worth while to record that later, when its effects were ascertained, Mr. George F. Baer, president of the Reading Railroad, publicly characterized it as the most beneficial thing that had ever happened to coal operators. Mr. Roosevelt had to deal with another strike in another manner in December of the year following, when he sent Federal troops to Goldfield, Nevada, to protect life and property from the violence inspired by the Western Federation of Miners. But a far worse trouble than either of these occurred at Fort Brown, Brownsville, Texas, the rights and wrongs of which were so confused in the public mind that Mr. Roosevelt's course was open to severer and more lasting criticism. On the night of August 13, 1906, a riot took place in which one citizen was killed, another wounded, and the Chief of Police seriously injured. Soldiers of the regular army — of a colored regiment — were accused of this by the townspeople. Bad blood had been existing for some time, and the theory (adopted by the Secretary of War after an investigation) was that from nine to twenty men from a battalion of 170 had planned this riot by way of revenge upon the civilians. A midnight sortie from barracks, a firing into certain houses, a return to their places in the ranks following a call to arms, appeared to be what had happened. But as silence and concealment impenetrably veiled everything, the President ordered the entire battalion dismissed without honor, never to be employed again in the civil or military service of the Government. Now if regulars had indeed fired upon citizens in such circumstances, extreme and quick and very public punishment was imperative. But the sweeping severity of the order while the facts were in the dark was widely condemned. Mr. Roosevelt later regretted to a friend in private that he had not balanced his act with a court of inquiry for every commissioned officer at the Post. Such had been his impulse; the War Department dissuaded him from it. Congressional investigation followed, with much bitter oratory. In the end, February 23 and 27, 1909, Congress provided an opportunity for these negro soldiers of the 25th Infantry to make themselves eligible for reinstatement. This whole incident was a great chance for Mr. Roosevelt's enemies, by this time ravenously on the watch for any chance whatever, even the smallest. We must now take up those economic and humane policies which were the cause of this ravenousness: “Trusts,” “Conservation,” “Employers Liability,” “Pure Food,” “Interstate Commerce” — here are the words which suffice to suggest what these various policies were.

Policies Economic. The conspicuous suit against the Northern Securities, brought by the Government during Mr. Roosevelt's first term under the Sherman Anti-Trust law, to compel the divorce of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific railroads has been already mentioned. Other suits — as for instance against the Tobacco Trust — were subsequently instituted: but in connection with this famous Sherman Law it must be most distinctly emphasized that Mr. Roosevelt has always, in constant messages and in other public utterances, urged that it be amended in such way as to define and direct its present altogether too general and sweeping scope. The divorce of the two systems in the Northern Securities was obviously “reasonable” from the public standpoint; the divorce of the Southern and Union Pacific, decreed in 1912, has been thought less “reasonable”; the situations were far from identical; yet logically, as the language of the Sherman Law now stands, the Court would have been obliged to interpolate some discretion of its own to escape its decision. The Court's use of the word “reasonable” in another case was a manifest exercise of common sense in the opinion of many people — and was also bitterly assailed by many other people as an arbitrary piece of “judicial legislation.” It has been Mr. Roosevelt's very sensible conviction that the language of no law should be able to place a Court in such a position. But so far, the Sherman Law stands unamended — to the great satisfaction of those who have no property to lose, and the great peril of business stability in the United States.

The Elkins Anti-Rebate Law had been passed in February, 1903, during the first term: It provided against discriminating favors from railroads to big shippers. On June 29, 1906, was passed the Railroad Rate Regulation Act, enlarging the powers of the Interstate Commerce Commission, providing for the regulation of rates charged by carriers engaged in interstate commerce, forbidding the issue of passes, providing for the publication of schedules and rates, for complaints and hearings before the Commission, with a review by the courts, and imposing penalties. The Commission was enlarged so as to consist of seven members with terms of seven years at a salary of ten thousand each a year. By a joint resolution passed shortly before this act, the Interstate Commerce Commission was empowered to look into the ownership by railroads of stock in other corporations, especially coal and oil companies. These laws are likely to stand historically among our epoch-making legislation.

March 4, 1907, an act provided for the issue and redemption of paper currency. May 30 of the fol lowing year an “Act to amend the National Banking Laws” was approved, providing for the issue of emergency currency by currency associations, limiting the note issue to five hundred million. A national monetary commission was also created — nine members from each house — to inquire and report as to our banking system. Later was proposed the plan known as the Aldrich Bill. Its provisions were so much better than anything we had or have, that it is highly unfortunate the unpopularity of Senator Aldrich should have prevented his bill from giving to his country the only national benefit it would ever have received from him. If our currency and banking system is to meet modern conditions intelligently (which it utterly fails to do at present) many of Mr. Aldrich's recommendations will have to be adopted.

Policies Humane. On June 11, 1906, was passed an act now known as the first “Employers Liability Act,” providing for the liability of common carriers by rail. The Supreme Court declared this unconstitutional. On April 22, 1908, another act was passed which has stood the test of the courts. By it railroads are held liable to their employees for death or injury caused by the negligence of the employers. This ended a doctrine of the common-law — the doctrine of “assumed risk” — established in days before steam and electricity had totally changed the conditions of transportation. The repeated messages of Mr. Roosevelt on this subject are responsible for the enlightened advance marked by the Act of 1908. These messages were also concerned with the necessity to limit the power of the courts to enforce injunctions, and with the prohibition of child labor. A law about this latter for the District of Columbia was passed. On March 4, 1907, was passed “An Act to promote the safety of employees and travelers upon railroads by limiting the hours of service of employees thereon.” It made unlawful the permitting of any employee to remain on duty for more than sixteen consecutive hours. An Act of May 30, 1908, provided for compensation for injuries to Federal employees.

The month of June, 1906, is associated with another memorable step taken by Mr. Roosevelt in the direction of humane policy. It is the second time in our history that a novel has been the quickener of public changes. In other countries, works of fiction have frequently exerted a marked influence upon opinion. In our own, there had been no case of this since “Uncle Tom's Cabin” until the appearance of “The Jungle.” This story by Mr. Upton Sinclair concerned the processes of meat-packing and the life of packers in Chicago; and beneath its sensational inaccuracies lay enough truth to set both America and England talking. It raised — and justly — a storm of excitement. England was as severely shocked as if her own skirts were spotless and she had never forced upon helpless China the opium grown in her Indian Empire. We differ from England in many ways, being less civilized and less hypocritical. Our impulse to make a clean breast of it and rise to higher things is our most precious national characteristic, and no president has ever surpassed Mr. Roosevelt in fostering it. He sent for the author of “The Jungle” and talked with him. It was on June 30, 1906, that an act was passed, known as the Agricultural Appropriation Act, providing for inspection of meat and food products used in interstate or foreign commerce, and imposing penalties. That this law today does less good than it ought, and that our only strict inspection is of meats exported to foreign countries because foreign countries also subject the meat to inspection, is due to the eternal vigilance of American rascals and the eternal inattentiveness of the American people. We allow the Beef Trust to sell us inferior meat and send the good meat abroad, where less is paid for it than we pay for the scrapings. On the same day in June was passed another most valuable act, rendered of less value through the reactionary influence of Mr. Taft's administration, and known as the “Pure Food and Drugs Act.” This forbade the manufacture, sale or transportation of adulterated or misbranded or poisoned or deleterious foods, drugs, medicines and liquors. In this case too the organized alertness of American rascals is triumphing over Democracy's unpiloted and helmless mind.

Conservation. More peculiarly his own than the South American, the Trust or even perhaps the humane policies, is Mr. Roosevelt's splendid attempt to stop the despoiling of our continent by water companies, land companies, lumber companies and all companies which would squat upon valuable fragments of the planet, and, keeping everybody out who could not pay excessive toll, selfishly exhaust natural supplies, regardless of the future's needs. Besides the forest reserves and regulations of timber cutting, the prevention of forest fires and provision for reforestation, a number of kindred matters fall under the general head of Conservation.

An Act providing for the preservation of Niagara Falls and prohibiting the diversion of water, except under certain conditions and with the consent of the Secretary of War, was passed June 29, 1906. If certain corporations using electric power end by having their way, Niagara Falls will be destroyed.

The improvement of inland waterways, repeatedly urged in Mr. Roosevelt's messages to Congress, was got at a little nearer by his appointment of the Waterways Commission, March 16, 1907. In May of the following year he invited a Conference of Governors at the White House to discuss this subject. The International Commission, composed of Americans and Canadians, had reported in January. The Internal Commission had reported in February. The report was sent to Congress by the President with a special message, recommending that suitable provisions be made for improving the inland waterways of the United States at a rate commensurate with the needs of the people as determined by competent authorities. Congress failed to take any action, or to provide for the continued existence of the Commission; so Mr. Roosevelt continued it by executive act and reappointed the former members. The unpatriotic conduct of this sixtieth congress is readily explained: The railroads feared competition if the waterways were developed and the vivacities of Mr. Roosevelt's phraseology regarding the lobbyists and legislators who were blocking, or doing their best to block, his reform had sped too sharply and accurately to elicit anything but rage from the particular and numerous individuals whom these barbed generalities struck. Besides the term “undesirable citizens,” he had coined another, “the predatory rich,” and he had spoken of a “rich men's conspiracy” against all such measures as the publicity of corporation finances, the control of Trusts, and the various policies fiscal, humane and conservational which he was forcing or attempting to force through Congress. It had not been long since a senator from the West was caught and convicted in land dealings of a dishonest nature. Mr. Roosevelt later named a senator from the South as implicated in transactions of a similar kind. And he then more than intimated that members of the Secret Service were needed to watch the conduct of our legislators at Washington. In consequence of his laws which impeded and his words which stung a great many “undesirable citizens,” a sea of abuse now arose against him as violent as that which once assailed Washington and Lincoln. Some one has collected the vocabulary of this language; and to read it is sufficient proof that Mr. Roosevelt is a great man; no other kind of man could arouse such prolonged vilification.

From May 13 to May 15, 1908, the conference of Governors he had called was in session at Washington, and was addressed by him on the subject of State and Federal rights.

At this gathering, the first of its kind ever held, besides governors or representatives from virtually all States of the Union, the foremost men in politics and affairs spoke or listened, and woman, never before included in State counsels, was represented by Sarah Platt Decker, President of the General Federation of Women's Clubs. Andrew Carnegie addressed the conference on the subject of iron and coal in relation to their exhaustion; Elihu Root dwelt upon the importance of the States directing their powers to preserving their natural resources; James J. Hill spoke about the wasteful use of the soil. Among other speakers were William J. Bryan, John Mitchell, Governor Glenn of North Carolina, Gifford Pinchot, and James R. Garfield, then Secretary of the Interior. A committee was appointed to compile statistics, and another conference was planned for 1909. In the following month (June 8) Mr. Roosevelt appointed a National Conservation Commission of forty-eight members representing the various States and Territories, which met in Washington the following December under the presidency of Gifford Pinchot, national forester, to prepare a report to the President for transmission to Congress on the resources of the country. Mr. Pinchot, as the personal representative of President Roosevelt, had visited Canada to carry an invitation to the Governor General and the Premier to be present at the conference called for February, 1909. A few months earlier (October 7) the Lake-to-the-Gulf Deep Waterway Association met in Chicago to further the development of the Great Lakes with the Mississippi and its branches. On March 3, 1909, the River and Harbor Appropriation Act was approved. It created the National Waterways Commission, composed of Members of Congress, to investigate questions of water transportation and the improvement of waterways and to recommend to Congress action upon these subjects. It will be noticed that this was almost exactly two years after the occasion when Congress ignored the message of Mr. Roosevelt urging some such step, and also exactly on the last day of his second term. Three months previous to this act, approved March 3, the National Rivers and Harbors Congress, composed of nearly 3,000 delegates from 44 States and Territories, held sessions in Washington during three days, when addresses of a similar character to those of the Conservation Commission, some of them given by the same men, were made; and the Act was of course the direct consequence of this conference. Two days before, on March 1, the House passed the Forest Reserve Bill.

Panama Canal. An act of June 29, 1906, provided for lock construction and thus ended the controversy between those who upheld this plan and those who advocated a sea-level canal. On November 17, 1907, the President announced that the Government would issue fifty million Panama bonds and interest-bearing certificates to the amount of a hundred million. In January, 1908, he issued an executive order defining the powers of the Isthmian Canal Commission and its chairmen. This was merely a comprehensive revision of the provisions of November 17, 1906, and subsequent orders. In March, 1908, some troubles of the Republic of Panama were pacified by Mr. Taft, but in July, as the election then approached, marines were sent to the Isthmus. What changes may come to the world in consequence of the canal cannot be at present imagined. Perhaps our destiny is to be more affected by it than anything directly due to an act of Mr. Roosevelt's. Our foreign relations, our labor conditions, the future of the Pacific coast, all are knit up with this huge enterprise, originated long before the day of Mr. Roosevelt, but the consummation of which he most certainly precipitated.

Immigration. By an act of June 29, 1906, a Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization was provided, laying down a uniform rule for the naturalization of aliens throughout the United States. An Act of February 20, 1907, provided for the levy and collection of a tax of four dollars upon every alien entering the United States. By this act certain classes of aliens, such as idiots and epileptics, were excluded; the importing of women for the purposes of prostitution was forbidden; as was also the prepayment of transportation of contract laborers. Undesirables were to be deported, anarchists excluded. Adequate provision for administration was unfortunately not made.

Most of us are aware that members of some twenty-five or thirty races come to our shores every year to remain. Many know that nearly thirty millions have so come since 1820; that in 1910 we had living among us nearly fourteen million foreign born people; that they are now arriving at the rate of nearly a million a year (Mr. Warne in his excellent and ominous book computes that during the past ten years every time the clock strikes the hour, night and day, one hundred immigrants step ashore) bringing languages, religions and customs at variance with our own. Our Constitution was made by English-speaking people for English-speaking people, by the self-governing for the self-governing; it rests upon the idea of a homogeneous population, with the same general traditions of law and life. With what stability it will rest upon a kaleidoscope of tribes and peoples speaking neither one another's language nor our own is a question very likely to concern the United States at some not distant day. Meanwhile the law of 1907 works little good; and we leave the incoming piebald hordes untaught.

After March 4, 1907, the Legislative, Executive and Judicial Appropriation Act of February 26 provided that the salaries of the vice-president, the speaker of the house and members of the Cabinet should be at the rate of twelve thousand a year and seventy-five hundred should be the compensation of congressmen. A fund not exceeding twenty-five thousand a year had been provided for the president's travelling expenses by an Act of June 23, 1906. In that month the state of Oklahoma was admitted to the Union. Certain further foreign agreements should be mentioned: A United States Court for China (June 30, 1906); a resolution authorizing the President to consent to a modification of the bond for our twenty-four millions received from China as indemnity on account of the Boxer disturbances of 1900, remitting about half this sum as an act of friendship (May 25, 1908). This led in the November following to the sending of Tang Shao Yi, Governor of Mukden Province, by the Chinese Government as special envoy to express China's thanks. He announced in San Francisco that the thirteen millions and odd remitted would be used in sending Chinese students to this country. In this same year the Senate ratified arbitration treaties with France, Italy, Mexico, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Spain, Portland, Great Britain, the Netherlands and Japan. With Japan this was the first treaty since the re-establishment of the friendly relations broken off in 1906 on account of the assaults upon Japanese subjects in San Francisco.

Such are the chief acts and incidents of Mr. Roosevelt's second term. By some of them the number of his friends and enemies had been simultaneously increased. He had set machinery going which, if properly kept going, would curb the excesses of the corporations, shield the lives of their employees, keep the forests safe from monopolizing hands and make the waterways useful for transportation. An act of January 26, 1907, had for bidden national banks and corporations organized under Federal law to contribute money to political campaigns. The great public purveyors of food and drugs were to be watched. Here was enough machinery to benefit the many and control the few; and Mr. Roosevelt had been saying that Mr. Taft was the man to keep it going after him. Numbers of people wished Mr. Roosevelt to stay on. In November, 1907, Federal office-holders were active in advocating a third term, and he issued a letter forbidding them. A month later he repeated his announcement that he would not again become a candidate for the presidency. A month after that, January 30, 1908, Mr. Taft resigned as secretary of war to become the Republican candidate for president, Luke E. Wright succeeding him in the following July, five days after Mr. Taft's nomination. This nomination was opposed by Mr. Roosevelt's enemies from the moment they began to fear it might occur. Believing that Mr. Taft would keep the machinery going, they made a ticket according to their financial taste — Cannon and Sherman doing what they could to impair the powerful popular influence of Mr. Roosevelt's recommendation. Their latest weapon was the “rich men's panic” of the Autumn of 1907. Mr. Roosevelt had caused it, they said, by his incendiary threats against “big business.” Equally preposterous was the counter-assertion that “big business” had artificially induced the disaster to frighten Mr. Roosevelt and stop his talking. The panic did come immediately after a speech made by the President during a journey regarding waterways through the Mississippi Valley. It had to come one day or another; an ebb-tide in finance and credit had been flowing slowly round the world, and it reached us at the time predicted for it a year before the worst. But this truth is not even now universally known; and in 1907-1908 it was concealed for political purposes by some who did know it. Of the two false notions, unquestionably that one prevailed which laid the panic at the “rich man's” door. At the Republican Convention held in Chicago, June 25, 1908, the “demonstration” for Mr. Roosevelt lasted for forty minutes. The nomination could have been swept to him on the wave of enthusiasm raised by his name; it was only not swept to him through the energy and skill of those who were aiding him to carry out his determination against it and in favor of Mr. Taft.

Although the final acts of Congress in Mr. Roosevelt's second term, the Forest Reserve Bill passed by the House March 1, and the ratification by the senate of the Canadian Waterways Treaty, March 4, were in harmony with his policies, for many months the relations between him and both houses had been increasingly discordant, and he may be said to have stepped out of the White House amid lightnings and thunders. There was a day when George Washington swore furiously at a cabinet meeting that he would rather be in his grave than endure the malignity of the press and the politicians. Upon another day Lincoln wondered if it were worth while to give oneself to the service of this country. A similar disgust once darkened the spirit of General Grant. They were all anticipated by two Frenchmen, one of whom remarked: “I begin to see things as they are; it is time I should die,” and the other: “The better I know men the better I like dogs.” Vindictiveness on the part of those politicians and magnates whose intentions both as to legislation and the presidency had been partly or wholly thwarted by Mr. Roosevelt, was pursuing him by any means that could discredit or harass him. The Brownsville trouble had served them well, so in a petty way had the matter of the sentence “In God we trust” he had ordered to be left off the new coins. Congress had ordered this restored amid verbiage that dripped with scandalized piety. A new chance, most fruitful for many a long day, had turned up during the panic of 1907. Mr. Roosevelt had then replied to inquiries made by two representatives of the United States Steel Corporation that, while he could not advise its purchase of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company (to save a serious impending failure), nevertheless he felt it to be no public duty of his to interpose any objection. That such a purchase offered no ground for proceedings against the Steel Corporation was the opinion given to Mr. Roosevelt by Mr. Bonaparte, the attorney-general. It was seen that Mr. Roosevelt's conversation could be twisted into something that would look oblique; a secret support of trusts while openly denouncing them. The trust people themselves, through their politicians in the Senate, requested information from the president regarding this transaction. He refused to give it, referring to Mr. Bonaparte's opinion. Two days later the Senate ordered its judicial committee to investigate the matter — on the very same day (January 8, 1909) that the president's private letter to Senator Hale about there being members of Congress whose transactions needed watching by detectives was made public. It is not surprising that on February 20 the committee's report found that the president had exceeded his authority. This affair of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company was used against Mr. Roosevelt in later circumstances, as was the matter of the Harvester Trust. Obliquity on his part was again sought to be established. Why, when in office, had he not prosecuted this trust? He replied that at a full cabinet meeting Mr. Bonaparte had given his opinion there was not sufficient evidence upon which to base proceedings. This statement was immediately confirmed by Mr. Bonaparte himself. The person who preserved silence was Elihu Root, who had been present at the meeting. A word from him would have entirely cleared Mr. Roosevelt in every quarter; but Mr. Root in 1912 was no longer serving Mr. Roosevelt or his policies, he was serving his opponents with all his immense skill; and so this word was left unspoken.

After failing of nomination by the Republicans, in 1912, Mr. Roosevelt “bolted” a long predestined certainty, hoped for earlier by some people. A month later, at an extraordinary and exalted convention, whose deep feelings rendered even the newspaper men unable to scoff for several days, he organized the Progressive Party and became its candidate. A campaign followed, wonderful and devoted. Its chief incident was near its close, when Mr. Roosevelt was shot in the street at Milwaukee on his way to address a meeting. His instant words to the agitated crowd were not to hurt the assassin. “Don't hurt the man. Don't let any one hurt him.”[1] He addressed the meeting and then spent some ten days in a hospital. A thick fold of notes in his breast pocket prevented a fatal wound and his excellent health and life-long moderation of habit speeded his recovery.