The Strand Magazine/Volume 1/Issue 1/The Story of the Strand

The Story of the Strand.

STRAND is a great deal more than London's most ancient and historic street: it is in many regards the most interesting street in the world. It has not, like Whitehall or the Place de la Concorde, seen the execution of a king; it has never, like the Rue de Rivoli, been swept by grape-shot; nor has it, like the Antwerp Place de Meir, run red with massacre. Of violent incident it has seen but little; its interest is the interest of association and development. Thus it has been from early Plantagenet days, ever changing its aspect, growing from a riverside bridle-path to a street of palaces, and from the abiding-place of the great nobles, by whose grace the king wore his crown, to a row of shops about which there is nothing that is splendid and little that is remarkable. It is not a fine street, and only here and there is it at all striking or picturesque. But now, as of yore, it is the high road between the two cities—puissant London and imperial Westminster. From the days of the Edwards to this latest moment it has been the artery through which the tide of Empire has flowed. Whenever England has been victorious or has rejoiced, whenever she has been in sadness or tribulation, the Strand has witnessed it all. It has been filled with the gladness of triumph, the brilliant mailed cavalcades that knew so well how to ride down Europe; filled, too, with that historic procession which remains the high water-mark of British pageantry, in the midst of which the king came to his own again. The tide of Empire has flowed westward along the Strand for generations which we may number but not realise, and it remains to-day the most important, as it was once the sole, highway between the two cities.

STRAND is a great deal more than London's most ancient and historic street: it is in many regards the most interesting street in the world. It has not, like Whitehall or the Place de la Concorde, seen the execution of a king; it has never, like the Rue de Rivoli, been swept by grape-shot; nor has it, like the Antwerp Place de Meir, run red with massacre. Of violent incident it has seen but little; its interest is the interest of association and development. Thus it has been from early Plantagenet days, ever changing its aspect, growing from a riverside bridle-path to a street of palaces, and from the abiding-place of the great nobles, by whose grace the king wore his crown, to a row of shops about which there is nothing that is splendid and little that is remarkable. It is not a fine street, and only here and there is it at all striking or picturesque. But now, as of yore, it is the high road between the two cities—puissant London and imperial Westminster. From the days of the Edwards to this latest moment it has been the artery through which the tide of Empire has flowed. Whenever England has been victorious or has rejoiced, whenever she has been in sadness or tribulation, the Strand has witnessed it all. It has been filled with the gladness of triumph, the brilliant mailed cavalcades that knew so well how to ride down Europe; filled, too, with that historic procession which remains the high water-mark of British pageantry, in the midst of which the king came to his own again. The tide of Empire has flowed westward along the Strand for generations which we may number but not realise, and it remains to-day the most important, as it was once the sole, highway between the two cities.

What the Strand looked like when it was edged with fields, and the road, even now not very wide, was a mere bridle-path, and a painful one at that, they who know the wilds of Connemara may best realise. From the western gate of the city of London—a small and feeble city as yet to the Westminster Marshes, where already there was an abbey, and where sometimes the king held his court, was a long and toilsome journey, with the tiny village of Charing for halting-place midway. No palaces were there; a few cabins perhaps, and footpads certainly. Such were the unpromising beginnings of the famous street which naturally gained for itself the name of Strand, because it ran along the river bank—a bank which, be it remembered, came up much closer than it does now, as we may see by the forlorn and derelict water-gate of York House, at the Embankment end of Buckingham-street. Then by degrees, as the age of the Barons approached, when kings reigned by the grace of God, perhaps, but first of all by favour of the peers, the Strand began to be peopled by the salt of the earth.

Then arose fair mansions, chiefly upon the southern side, giving upon the river, for the sake of the airy gardens, as well as of easy access to the stream which remained London's great and easy highway until long after the Strand had been paved and rendered practicable for wheels. It was upon the water, then, that the real pageant of London life—a fine and well-coloured pageant it must often have been—was to be seen. By water it was that the people of the great houses went to their plots, their wooings, their gallant intrigues, to Court, or to Parliament. Also it was by water that not infrequently they went, by way of Traitor's Gate, to Tower Hill, or at least to dungeons which were only saved from being eternal by policy or expediency. This long Strand of palaces became the theatre of a vast volume of history which marked the rise and extension of some of the grandest houses that had been founded in feudalism, or have been built upon its ruins. Some of the families which lived there in power and pomp are mere memories now; but the names of many of them are still familiar in Belgravia as once they were in the Strand. There was, to start with, the original Somerset House, more picturesque, let us hope, than the depressing mausoleum which now daily reminds us that man is mortal. Then there was the famous York House, nearer to Charing Cross, of which nothing but the water-gate is left. On the opposite side of the way was Burleigh House, the home of the great statesman who, under God and Queen Elizabeth, did such great things for England. Burleigh is one of the earliest recorded cases of a man being killed by over-work. "Ease and pleasure," he sighed, while yet he was under fifty, "quake to hear of death; but my life, full of cares and miseries, desireth to be dissolved." The site of Burleigh House is kept in memory, as those of so many other of the vanished palaces of the Strand, by a street named after it; and the office of this magazine stands no doubt upon a part of Lord Burleigh's old garden. When Southampton House, Essex House, the Palace of the Savoy, and Northumberland House, which disappeared so lately, are added, we have still mentioned but a few of the more famous of the Strand houses.

But the Strand is distinguished for a vast deal more than that. Once upon a time, it was London's Belgravia. It was never perhaps the haunt of genius, as the Fleet-street tributaries were; it was never an Alsatia, as Whitefriars was, nor had it the many interests of the City itself. But it had a little of all these things, and the result is that the interest of the Strand is unique. It would be easy to spend a long day in the Strand and its tributaries, searching for landmarks of other days, and visiting sites which have long been historic. But the side streets are, if anything, more interesting than the main thoroughfare, and they deserve a special and separate visit, when the mile or so of road-way between what was Temple Bar and Charing Cross has been exhausted. Could Londoners of even only a hundred years ago see the Strand as we know it, they would be very nearly as much surprised as a Cockney under the Plantagenets, who should have re-visited his London in the time of the Georges. They who knew the picturesque but ill-kept London of the Angevin sovereigns found the Strand a place of torment.

In 1353 the road was so muddy and so full of ruts that a commissioner was appointed to repair it at the expense of the frontagers. Even towards the end of Henry VIII.'s reign it was "full of pits and

sloughs, very perilous and noisome." Yet it was by this miserable road that Cardinal Wolsey, with his great and stately retinue, passed daily from his house in Chancery-lane to Westminster Hall. In that respect there is nothing in the changed condition of things to regret; but we may, indeed, be sorry for this: that there is left, save in its churches, scarcely a brick of the old Strand.

Still there are memories enough, and for these we may be thankful. Think only of the processions that have passed up from Westminster to St. Paul's, or the other way about! Remember that wonderful cavalcade amid which Charles II. rode back from his Flemish exile to the palace which had witnessed his father's death. Nothing like it has been seen in England since. Evelyn has left us a description of the scene, which is the more dramatic for being brief: "May 29, 1660. This day His Majesty Charles II. came to London, after a sad and long exile and calamitous suffering, both of the King and Church, being seventeen years. This was also his birthday, and, with a triumph above 20,000 horse and foot, brandishing their swords and shouting with inexpressible joy; the way strew'd with flowers, the bells ringing, the streets hung with tapestry, fountains running with wine; the mayor, aldermen, and all the companies in their liveries, chains of gold, and banners; lords and nobles clad in cloth of silver, gold, and velvet; the windows and balconies well set with ladies; trumpets, music, and myriads of people. . . . They were eight hours passing the city, even from two till ten at night. I stood in the Strand, and beheld it, and bless'd God." A century earlier Elizabeth had gone in state to St. Paul's, to return thanks for the destruction of the Armada. Next, Queen Anne went in triumph up to St. Paul's, after Blenheim; and, long after, the funeral processions of Nelson and Wellington were added to the list of great historic sights which the Strand has seen. The most recent of these great processions was the Prince of Wales's progress of thanksgiving to St. Paul's in 1872.

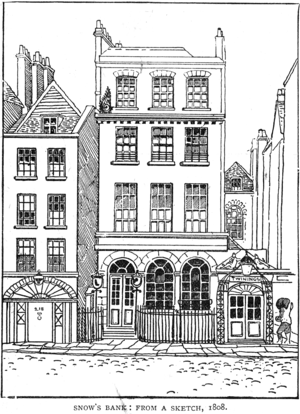

Immediately we leave what was Temple Bar, the Strand's memories begin. We have made only a few steps from Temple Bar, when we come to a house—No. 217, now a branch of the London and Westminster Bank—which, after a long and respectable history, saw its owners at length overtaken by shame and ruin. It was the banking-house of Strahan, Paul & Bates, which had been founded by one Snow and his partner Walton in Cromwell's days. In the beginning the house was "The Golden Anchor," and Messrs. Strahan & Co. have among their archives ledgers (kept in decimals!) which go back to the time of Charles II.

In 1855 it was discovered that some of the partners had been using their customers' money for their own pleasures or necessities. The guilty persons all went to prison; one of the few instances in which, as in the case of Fauntleroy, who was hanged for forgery, English bankers have been convicted of breach of trust. Adjoining this house is that of Messrs. Twining, who opened, in 1710, the first tea-shop in London. They still deal in tea, though fine ladies no longer go to the Eastern Strand in their carriages to drink it, out of curiosity, at a shilling a cup.

One of the most interesting buildings in Essex-street, the "Essex Head" tavern, has only just been pulled down. There it was that Dr. Johnson founded "Sam's" Club, so named after the landlord, Samuel Graves. Dr. Johnson himself drew up the rules of the club, as we may see in Boswell's "Life." The chair in which he is reported to have sat was preserved in the house to the end. It is now cared for at the "Cheshire Cheese" in Fleet-street. A very redoubtable gentleman who formerly lived in Essex-street was Dr. George Fordyce, who for twenty years drank daily with his dinner a jug of strong ale, a quarter of a pint of brandy, and a bottle of port. And he was able to lecture to his students afterwards!

Nearly opposite Essex-street stands one of the most famous of London landmarks—the church of St. Clement Danes. Built as recently as 1682, it is the successor of a far older building. Its most interesting association is with Dr. Johnson, whose pew in the north gallery is still reverently kept, and an inscription marks the spot. In this church it was that Miss Davies, the heiress, who brought the potentiality of untold wealth into the family of the Grosvenors, was married to the progenitor of the present Duke of Westminster. St. Clement Danes is one of the few English churches with a carillon, which is of course set to psalm tunes. Milford-lane, opposite, was once really a lane with a bridge over a little stream which emptied into the Thames. Later on it marked the boundary of Arundel House, the home of the Dukes of Norfolk, who have built Arundel, Norfolk, Howard, and Surrey streets upon its site. In the time of Edward VI. the Earl of Arundel bought the property for forty pounds, which would seem to have been a good bargain even for those days. In Arundel House died "old Parr," who, according to the inscription upon his tomb in Westminster Abbey, lived to be 152 years old. Happily for himself he had lived all his life in Shropshire, and the brief space that he spent in London killed him.

The streets that have been built upon the site of old Arundel House are full of interesting associations. The house at the south-western corner of Norfolk and Howard-streets—it is now the "Dysart Hotel"—has a very curious history. A former owner—it was some sixty years since—was about to be married. The wedding breakfast was laid out in a large room on the first floor, and all was ready, except the lady, who changed her mind at the last minute. The jilted bridegroom locked up the banquet-chamber, put the key in his pocket, and, so the story runs, never again allowed it to be entered. There, it was said, still stood such mouldering remains of the wedding breakfast as the rats and mice had spared. Certainly the window curtains could for many years be seen crumbling to pieces, bit by bit, and the windows looked exactly as one would expect the windows of the typical haunted chamber to look. It is only of late that the room has been re-opened. The name of the supposed hero of this story has often been mentioned, but, since the story may quite possibly be baseless, it would be improper to repeat it. But there is no doubt whatever that for nearly half a century there was something very queer about that upper chamber.

This same Howard-street was the scene, in 1692, shortly after it was built, of a tragedy which remained for generations in the popular memory. It took place within two or three doors of the "Dysart Hotel." The central figure of the pitiful story was Mrs. Bracegirdle, the famous and beautiful actress. One of her many admirers, Captain Richard Hill, had offered her marriage, and had been refused. But he was not to be put off in that way. If he could not obtain the lady by fair means he was determined to get her by force. He therefore resolved, with the assistance of Lord Mohun—a notorious person, who was afterwards killed in Hyde-park in a duel with the Duke of Hamilton—to carry her off. They stationed a coach in Drury-lane, and attempted to kidnap her as she was passing down the street after the play. The lady's screams drew such a crowd that the abductors were forced to bid their men let her go. They escorted her home (a sufficiently odd proceeding in the circumstances), and then remained outside Mrs. Bracegirdle's house in Howard-street "vowing revenge," the contemporary accounts say, but against whom is not clear. Hill and Lord Mohun drank a bottle of wine in the middle of the street, perhaps to keep their courage up, and presently Mr. Will Mountfort, an actor, who lived in Norfolk-street, came along. Mountfort had already heard what had happened, and he at once went up to Lord Mohun (who, it is said, "embraced him very tenderly"), and reproached him with "justifying the rudeness of Captain Hill," and with "keeping company with such a pitiful fellow." "And then," according to the Captain's servant, "the Captain came forward and said he would justify himself, and went towards the middle of the street and drew." Some of the eye-witnesses said that they fought, but others declared that Hill ran Mountfort through the body before he could draw his sword. At all events, Hill instantly ran away, and when the watch arrived they found only Lord Mohun, who surrendered himself. He seems to have had no part in the murder, and his sword was still sheathed when he was made prisoner. It is said that Hill already had a grudge against Mountfort, whom he suspected of being Mrs. Bracegirdle's favoured lover. But the best contemporary evidence agrees that the lady's virtue was "as impregnable as the rock of Gibraltar."

Nearly opposite the scene of this brutal tragedy, the church of St. Mary-le-Strand was built some five-and-twenty years later. It is a picturesque building, and makes a striking appearance when approached from the west. It has of late been more than once proposed that it should be demolished, at once by reason of the obstruction which it causes in the roadway, and because of its ill-repair. But since it has now been put into good condition, the people who would so gaily pull down a church to widen a road will perhaps not be again heard from. According to Hume, Prince Charles Edward, during his famous stolen visit to London, formally renounced in this church the Roman Catholic religion, to strengthen his claim to the throne; but there has never been any manner of proof of that statement. The site of St. Mary-le-Strand was long famous as the spot upon which the Westminster maypole stood, and what is now Newcastle-street was called Maypole-lane down to the beginning of the present century. At the Restoration, a new maypole, 134 feet high, was set up, the Cromwellians having destroyed the old one, in the presence of the King and the Duke of York. The pole is said to have been spliced together with iron bands by a blacksmith named John Clarges, whose daughter Anne married General Monk, who, for his services in bringing about the Restoration, was created Duke of Albemarle. Three or four suits were brought to prove that her first husband was still living when she married the Duke, and that consequently the second (and last) Duke of Albemarle was illegitimate, but the blacksmith's daughter gained them all. Near the Olympic Theatre there still exists a Maypole-alley.

It is hardly necessary to say that the present Somerset House, which is exactly opposite the church of St. Mary-le-Strand, is not the original building of that name. People—praise to their taste!—did not build in that fashion in the time of the Tudors. The old house, built by not the cleanest means, by the Protector Somerset, was "such a palace as had not been seen in England." After Somerset's attainder it became the recognised Dower House of the English Queens. It was built with the materials of churches and other people's houses. John of Padua was the architect, and it was a sumptuous palace indeed; but if Somerset ever lived in it, it was for a very brief space. One of the accusations upon which he was attainted was that he had spent money in building Somerset House, but had allowed the King's soldiers to go unpaid. It was close to the Water Gate of Somerset House that the mysterious murder of Sir Edmundbury Godfrey took place in 1678. The story of the murder is so doubtful and complicated that it is impossible to enter upon it here. Sir Edmundbury was induced to go to the spot where he was strangled under the pretence that, as a justice of the peace, he could stop a quarrel that was going on. Titus Oates, the most finished scoundrel ever born on British soil,

Another interesting bit of the southern side of the Strand is the region still called The Savoy. The old Palace of the Savoy was built by Simon de Montfort, but it afterwards passed to Peter of Savoy, uncle of Queen Eleanor, who gave to the precinct the name which was to become historical. There it was that King John of France was housed after he was taken prisoner at Poictiers; and there too he died. The Palace of the Savoy was set on fire and plundered by Wat Tyler and his men in 1381. It was rebuilt and turned into a hospital by Henry VII. In the new building the liturgy of the Church of England was revised after the restoration of Charles II.; but the most interesting association of the place must always be that there Chaucer wrote a portion of the "Canterbury Tales," and that John of Ghent lived there. After many vicissitudes and long ruin and neglect, the last remains of the Palace and Hospital of the Savoy were demolished at the beginning of the present century, to permit of a better approach to Waterloo Bridge.

Coutts' Banking House, 1853: from a drawing by T. Hosmer Shepherd.

A little farther west, in Beaufort-buildings, Fielding once resided. A contemporary tells how he was once hard put to it to pay the parochial taxes for this house. The tax-collector at last lost patience, and Fielding was compelled to obtain an advance from Jacob Tonson, the famous publisher, whose shop stood upon a portion of the site of Somerset House. He returned home with ten or twelve guineas in his pocket, but meeting at his own door an old college chum who had fallen upon evil times, he emptied his pockets, and was unable to satisfy the tax-gatherer until he had paid a second visit to the kindly and accommodating Tonson. Another of the great Strand palaces stood on this site—Worcester House, which, after being the residence of the Bishops of Carlisle, became the town house of the Earls of Worcester. Almost adjoining stood Salisbury, or Cecil House, which was built by Robert Cecil, first Earl of Salisbury, a son of the sage Lord Burghley, whose town house stood on the opposite side of the Strand. It was pulled down more than two hundred years ago, after a very brief existence, and Cecil and Salisbury streets were built upon its site. Yet another Strand palace, Durham House, the "inn" of the Bishops Palatine of Durham, stood a little nearer to Charing Cross. It was of great antiquity, and was rebuilt as long ago as 1345. Henry VIII. obtained it by exchange, and Queen Elizabeth gave it to Sir Walter Raleigh. The most interesting event that ever took place in the house was the marriage of Lady Jane Grey to Lord Guildford Dudley. Eight weeks later she was proclaimed Queen, to her sorrow. Still nearer to Charing Cross, and upon a portion of the site of Durham House, is the famous bank of the Messrs. Coutts, one of the oldest of the London banks. The original Coutts was a shrewd Scotchman, who, by his wit and enterprise, speedily became rich and famous. He married one of his brother's domestic servants, and of that marriage, which turned out very happily, Lady Burdett-Coutts is a grandchild. Mr. Coutts' second wife was Miss Harriet Mellon, a distinguished actress of her day, to whom he left the whole of his fortune of £900,000. When the lady, who afterwards became Duchess of St. Albans, died in the year of the Queen's accession, that £900,000 formed the foundation of the great fortune of Miss Angela Burdett, better known to this generation as Lady Burdett-Coutts. Messrs. Coutts' banking-house is an interesting building, with many portraits of the early friends and customers of the house, which included Dr. Johnson and Sir Walter Scott. The cellars of the firm are reputed to be full of boxes containing coronets and patents of nobility. Upon another part of the site of Durham House the brothers Adam built, in 1768, the region called the Adelphi. There, in the centre house of Adelphi-terrace, with its wondrous view up and down the river, died in 1779 David Garrick.

was not, properly speaking, in the Strand at all. It may therefore be sufficient to recall that it was built in 1605, and became the home of the Percies in 1642. It was sold to the Metropolitan Board of Works, with great and natural reluctance, for half a million of money; and the famous blue lion of the Percies, which for so long stood proudly over the building, was removed to Sion House.

The northern side of the Strand is not quite so rich in memories as the side which faced the river, but its associations with Lord Burleigh, that calm, sagacious, and untiring statesman, must always make it memorable. Burleigh House, the site of which is marked by Burleigh and Exeter-streets, was the house from which he governed England with conspicuous courage, devotion, and address. There, too, he was visited by Queen Elizabeth. According to tradition she wore, on that occasion, the notorious pyramidal head-dress which she made fashionable, and was besought by an esquire in attendance to stoop as she entered. "For your master's sake I will stoop, but not for the King of Spain," was the answer which might have been expected from a daughter of Henry VIII. Lord Burleigh lived there in considerable state, spending thirty pounds a week, which in Elizabethan days was enormous. There, broken with work and anxiety, he died in 1598. When his son was made Earl of Exeter he called it Exeter House. This historical house was not long in falling upon evil days. By the beginning of the eighteenth century a part of it had been demolished, while another part was altered and turned into shops, the new building being christened "Exeter Change." Nearer to our own time the "Change" became a kind of arcade, the upper floor being used as a wild-beast show. When it was "Pidcock's Exhibition of Wild Beasts" an imitation Beef-eater stood outside, in the Strand, inviting the cockney and his country cousin to "walk up." The roaring of the animals is said to have often frightened horses in the Strand. "Exeter Change" was the home of "Chunee," an elephant as famous in his generation—it was more than sixty years since—as "Jumbo" in our own. "Chunee," which weighed five tons, and was eleven feet high, at last became unmanageable, and was shot by a file of soldiers, who fired 152 bullets into his body before killing him. His skeleton is still in the Museum of the College of Surgeons, in Lincoln's-inn-fields. It should be remembered that in Exeter-street Dr. Johnson lodged (at a cost of 4½d. per day) when he began his struggle in London. A little farther east once stood Wimbledon House, built some three centuries ago by Sir Edward Cecil, Viscount Wimbledon, a cadet of the great house founded by Lord Burleigh. Stow records that the house was burned down in 1628, the day after an accidental explosion of gunpowder demolished the owner's country seat at Wimbledon. Nearly all the land hereabouts still belongs to the Cecils. Upon a portion of the site of Wimbledon House arose the once famous "D'Oyley's Warehouse," where a French refugee sold a variety of silk and woollen fabrics, which were quite new to the English market. He achieved great success, and a "D'Oyley" is still as much a part of the language as an "antimacassar"—that abomination of all desolation. The shop lasted, at 346, Strand, until some thirty years ago. The Lyceum Theatre, which also stands upon a piece of the site of Exeter House, occupies the spot where Madame Tussaud's waxworks were first exhibited in 1802.

With Bedford House, once the home of the Russells, which stood in what is now Southampton-street, we exhaust the list of the Strand palaces. There is but little to say of it, and it was pulled down in 1704. Southampton-street—so called after Rachel, the heroic wife of Wm. Lord Russell, who was a daughter of Thomas, Earl of Southampton—Tavistock-street, and some others were built upon its site. It was in Southampton-street that formerly stood the "Bedford Head," a famous and fashionable eating-house. Pope asks:—

"When sharp with hunger, scorn you to be fed,

Except on pea-chicks at the 'Bedford Head'?"

He who loves his London, more especially he who loves his Strand, will not forget that No. 332, now the office of the Weekly Times, was the scene of Dickens' early work in journalism for the Morning Chronicle.

It would be impossible to find a street more entirely representative of the development of England than the long and not very lovely Strand. From the days of feudal fortresses to those of penny newspapers is a far cry; and of all that lies between it has been the witness. If its stones be not historic, at least its sites and its memories are; and still it remains, what it ever has been, the most characteristic and distinctive of English highways.