Three Years in Europe, 1868 to 1871/Chapter 11

CHAPTER XI.

The Rhineland, 1893.

On the 21st August 1893, I revisited Cologne after 22 years. Europe has passed through a revolution within these 22 years, the new German Empire has been built up and consolidated, and the Cathedral of Cologne, commenced six centuries ago, has been completed by the first ruler of the new German Empire. It is the most magnificent Gothic edifice in the world, as the church of St. Peter is the finest edifice in the Roman style.

The town of Cologne traces back its history to the first century of the Christian era when Agrippina the mother of Nero founded here a colony of Cologne.Roman veterans to keep the German barbarians in check. But Rome decayed in time, the German barbarians rose to be the most powerful nations in Europe, and in the eighth century the great Charlemagne raised the bishopric of Cologne into an archbishopric.

Five centuries then rolled away, centuries of Feudalism and of Crusades, and archbishop Conrad laid the foundation stone of the present noble Cathedral.cathedral in 1248. In two hundred years the work was sufficiently advanced to be fitted up for service, but religious enthusiasm declined by the end of the fifteenth century, and the unfinished building was left with a temporary roof.

Three centuries then rolled away, centuries of Reformation, of maritime discoveries and colonization, of European wars and the French Revolution, and in the wars of the Revolution, the French used the delapidated old edifice as a hay-magazine in 1796! But after Waterloo, the kings of Prussia began restoring and completing the hoary but unfinished edifice, and it was nine years after Sedan and the founding of the new German Empire, that the last stone of the huge southern tower was placed in position, and the completion of the Cathedral was celebrated in the presence of Emperor William I. in 1880.

I love to recall historical facts when I visit old edifices and structures and even hoary ruins. Nothing so interests me as the story of human progress,—the march of nations through ages of struggle to freedom and enlightenment. And the noblest edifices of Europe owe much of their interest to the grand historic past which seems to be sculptured on their walls.

For the rest, the Cologne Cathedral is in itself a most imposing structure. The towers are the loftiest church towers in Europe, being over five hundred feet high; and standing within the cathedral one is lost in admiration as he looks up to the lofty ceiling borne on 56 lofty pillars, and displaying a wealth of art which beggars description.

From Cologne I came to Wiesbaden, one of the oldest watering places in Germany, and now the capital of the Prussian District of Wiesbaden. Wiesbaden.The place is resorted to every year by thousands of Germans and hundreds of foreigners who seek to renovate their health by the use of its waters. I was one of them; for after years of hard work in heavy or unhealthy Bengal Districts, like Mymensing and Burdwan, Dinajpur and Midnapur, I had felt the need for a change, and had come to Europe in 1893. I had brought my ailments with me, and I suffered from malarial fever for six weeks in England before I had done with it. And I was also susceptible to rheumatism, and Wiesbaden, they say, is the best place for cure of that disease. One has need to be more careful of his health at forty-five than at the age of twenty-five, and I accordingly gave up all idea of visiting the Chicago Exhibition, and decided to spend the summer of 1893 in this quiet watering place, Wiesbaden.

The treatment which is prescribed here is much the same as elsewhere. Bath in the tepid spring water every morning, the patient lying in the water Healing Spring.for half an hour, and two or three courses of that water for drink during the day. This treatment, continued for a month, is very weakening; one is much weaker and thinner after the period; but in nine cases out of ten he gets rid of his ailments, and is a sounder and healthier man for years after. This certainly was the case with me.

The weather was sunny and mild, and my days passed pleasantly enough. I read a little German every day with a young Russian student who had been educated in Germany and was stopping in the same boarding house with me, and I spent my spare moments in the pleasant task of translating Kiratarjuniyam into English verse. We formed parties and made frequent excursions into neighbouring places through woods which surround Wiesbaden on every side, and occasionally we made a trip down the Rhine. In the evenings, I sometimes went to theatres where I could follow the acting when I knew the story. The lady of the establishment was a person of education and much natural benevolence, and tried to make things pleasant for us. Another elderly lady from Brussels, an English woman by birth who had married a Belgian, took me under her sheltering wings, shewed me all that was to be seen round about Wiesbaden, and was very kind to me when I saw her again a few months after at Brussels. Another elderly lady, very theosophical and pious in her professions, and very whimsical and selfish in her actions, was quite a character for study! There was a German visitor from Dantzig with his very amiable and devoted wife, who floundered over her English as hopelessly as I floundered over my German whenever we attempted to talk! An English Colonel and his wife and a few others completed the inmates of the house at the time.

The gardens of Wiesbaden where games and music and entertainments were constantly going on are very fine, but the beauty and the glory of the town is its situation in the midst of natural forests stretching for miles in different directions. One leaves the town German forests.and strolls for hours amidst these primeval forests, which are kept in good order, with roads and paths leading in different directions. It is a pleasure and a luxury to sit under one of the trees, book in hand, and spend a summer afternoon in the quiet solitude. Many continental towns have such natural forests preserved close to them. Paris has Bois de Boulogne, and Brussels, Vienna, Berlin have all their garden-like forests, but it is German towns which have the most extensive forests close to them, because Germany is full of forests. The State derives a revenue from these forests, and our forest officers in India study the system in Germany for a season or two before they go out to India.

Many were the excursions which we made by the pleasant forest paths, up and down hills, to neighbouring places, and wherever we went, a substantial cup of chocolate or of a kind of sour-milk, not unlike the Indian Dahi, refreshed us after our labours. Sonnenberg and Neroberg and Eisenhand are all places within easy range of Wiesbaden which we visited, and from Biebrich on the Rhine we went down by steamer to see the national monument of Germania, erected after the Franco-German War near Rudesheim famous for its wines. The monument is a colossal figure A national monument on the Rnine.of Germania, 33 feet high, with oak-leaves on her head, the imperial crown in her right hand, and a drawn sword in her left. She stands on a pedestal, 78 feet high, and erected on a hill 740 feet above the level of the Rhine, and seems to guard the Fatherland by keeping an eternal watch over that historic river.

Dear Fatherland! no fear be thine!

Brave hearts and true shall watch the Rhine!

The Watch on the Rhine. (Blackie's Translation.)

I made longer excursions also to other German towns situated on or near the Rhine; and among them Frankfort on Main is certainly historically the most interesting. A Roman military station, Frankfort.like Cologne, in the first century, Frankfort was a seat of royal residence under Charlemagne, and was in succeeding ages looked upon as the capital of the East Franconian Empire. And from the time of Frederick Barbarossa, Frankfort was the place of the election of the German Emperors for seven centuries, until the old empire was dissolved in 1806 by Napoleon Bonaparte. From 1815 to 1866 it was one of the free cities of Germany, and in 1866 it was taken by the Prussians. Frankfort, like Wiesbaden, is therefore now a portion of Prussia.

Venerable on account of its long and eventful history, Frankfort is now doubly interesting to the modern tourist as the birthplace of Goethe. In a century which has produced Byron and Scott, Birthplace of Goethe.Schiller and Victor Hugo, Goethe stands foremost, as the greatest literary genius of the age! I visited the house in which he was born and his fine statue by Schwanthaler, as well as the statue of the poet Schiller not far off.

More interesting to the student of mediæval history is the old market place of Römerberg, and the famous old Town Hall of Römer built nearly Old Town Hall.six centuries ago, and containing the very room where the electors met to elect German Emperors for centuries. Close to it is Saalhof, occupying the site where Charlemagne built an imperial palace of that name. And not far is the famous Cathedral of Frankfort rebuilt in the thirteenth century. Cathedral.The Cathedrals of Europe always strike me as silent memorials of a past age of which everything else is gone, witnesses of wars and triumphs and celebrations through centuries, witnesses of the progress of nations from feudal barbarism and to modern culture and freedom!

The Jews were a proscribed race in Europe in the middle ages, and the Jews' quarter in Frankfort with its tortuous lanes and dingy houses tells a tale Jews' quarters.of the history of this scheming, long-suffering, keen-witted people among the Nazarenes through centuries of oppression. Many of these dingy houses have been removed, but the house where Rothschild, the architect of one of the richest houses in Europe, was born, is preserved and shewn to the tourist.

In the northern and more open parts of the town, the tourist never fails to visit the Statue of Areadne.famous statue of Areadne on the Panther in Bethmann's Museum. He then walks through fine open streets and gardens, past the new Opera House, to the railway station. The Frankfort railway station is the best arranged station I have seen anywhere.

Frankfort is situated on the Main, a tributary of the Rhine, and the ancient city of Maintz or Mayence is situated Mayence.where this tributary joins the Rhine. Like other great German towns it has its old Cathedral, rebuilt after destruction in the twelfth century, and it boasts of a statue of Cathedral.Guttenberg the inventor of printing who was born in this town in the 14th century. The earliest book printed with movable type is said Guttenberg and the invention of printing.to have been the 42-line bible printed in 1450 to 1455.

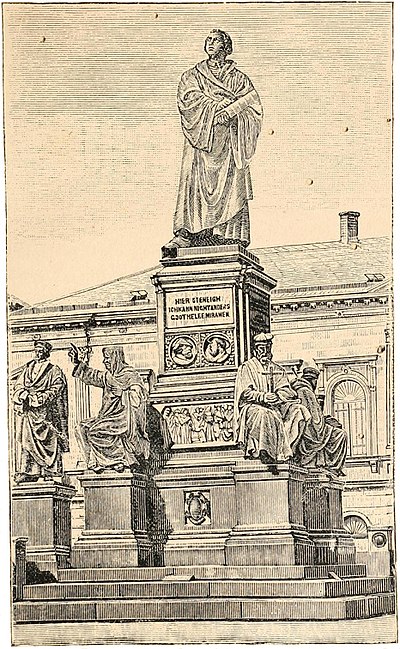

Going up the course of the Rhine from Mayence, one comes to the historic town of Worms, redolent of the fame of a greater man than Guttenberg,—of Martin Luther. Worms was a free town of the German Empire, and when Charles V. Worms. Statue of Luther.succeeded to the empire, he convened his first diet of the Sovereigns and States at Worms in 1521. An order was issued for the destruction of Luther's heretical books published in the previous year, and Luther himself was summoned to appear before the diet. He attended, and all Germany was moved by his heroism. He declined to retract, and used those words which are inscribed on his monument now erected at Worms:—"Here I take my stand. I can do no otherwise. So help me God. Amen." The statue is of bronze, 11 feet high, and is surrounded by statues of other bold spirits who also fought the battle of freedom and reformation. At the corners of the chief pedestal are his four predecessors, Waldus (died 1197), Wycliffe (died 1387), Huss (died 1415), and Savonarola (died 1498.)

Worms, like Mayence, has an old and famous Cathedral dating from the twelfth century. Worms is also the centre of many ancient and romantic Cathedral.legends, preserved in the German national epic, Nibelungen Lied.

Leaving Worms, and going further up the Rhine, one comes to Manhiem where the tributary Neckar falls into the Rhine. Manhiem is not a place of much interest, but the university town of Heidelberg on the Neckar is replete with interest. The town is situated Heidelberg.just where the Neckar leaves the wild and mountainous country to the west and flows out into the open valley of the Rhine. It was the capital of the Palatinate for five hundred years, and its castle was built by Count Palatine Rudolph I. at the close of the thirteenth century. And the University of Heidelberg is the oldest in Germany being founded by Elector Rupert I. in the 14th century.

The castle has an eventful history, and is now in ruins. In the disastrous Thirty Years' War, Heidelberg Castle.and the whole of the Palatinate, like other parts of Germany, went through untold sufferings, and were partially depopulated, but the castle survived. Then followed the cruel wars of Louis XIV., and the French General caused the foundations of the castle to be blown up and the palace to be burned down! Portions were rebuilt afterwards, but was again destroyed by lightning, and noble ruins are all that the tourist sees and admires at the present day. The ivy covered towers and the vast walls form the most magnificent ruin in all Germany.

The University too survived with difficulty the Thirty Years' War and the French wars of Louis XIV. University.It has 1,000 to 1,200 students in winter, and duelling is still in vogue among the German university students.

Going further up the Rhine from Manhiem we come to the historic town of Speyer or Spires, one of the free cities of the Empire like Frankfort and Worms. Here too numerous imperial diets were held, Spires.and it was after the diet of 1829, held here by Charles V., that the Princes and States who had espoused the cause of the Reformation received the name of Protestants from their protest against the resolution of the hostile majority. The Cathedral of Spires, the burial place of old German Emperors, Cathedral.dates from the eleventh century. It is an imposing edifice, and is the principal attraction of the place.

Leaving Spires, and travelling up the course of the Rhine, one comes to Strassburg Strassburg.the famous capital of Alsace. It was a free city of the German Empire, and had a university, founded in 1621. In the same century the town and the whole of Alsace were annexed to France by Louis XIV., and Alsace formed a part of France for two centuries, until in 1871 it was wrested from France and reannexed to Germany. The old and imposing Cathedral of Strassburg, dating from the twelfth century, still stands in this venerable old Cathedral.town,—surviving the Thirty Years' War and the French annexation, the French Revolution and the German annexation, like some venerable old Yogi rapt in contemplation, and far above all sublunar feuds, passions and dissensions. It was a Sunday when I was in Strassburg; I attended the Cathedral and witnessed the most solemn service and heard the most solemn music that I have seen or heard anywhere.

From Strassburg and Alsace, one naturally proceeds to Metz and Lorraine which have shared a similar fate after the war of 1871. Like Strassburg, Metz.Metz was a free town of the German Empire in the olden days, and boasts of a great Cathedral dating from the thirteenth century. The town was annexed to France in 1556, Cathedral.and formed a part of France for over three hundred years, and the population of Lorraine are Frenchmen to the backbone. To have wrested Alsace and Lorraine from France after the war of 1871, and changed the frontier line between Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.France and Germany which had subsisted in spite of temporary interruptions for two and three centuries, was an act of insolent pride and doubtful wisdom which has perpetuated jealousies and ill feeling, and has sown the seeds of a more disastrous war in the future than we have witnessed in our generation.

What disastrous wars these frontier provinces of Alsace and Lorraine have seen! Wave after wave of European war have swept over these unfortunate regions, and scarcely a generation has passed when they have known peace. Previous wars.Why these interminable feuds? Wherefore should civilized men eternally wage deadly wars against each other?

Historians and moralists attribute these wars to the ambition of kings or to the restlessness of nations, but a careful student can detect the operation of deeper causes even in the uncertain and changeable phenomena of war. Contending principles, which do not always appear on the surface, bring about wars, and the termination of a long war often determines the triumph of a principle, and the downfall of another. It is a matter for regret that these great principles cannot be decided except by disastrous wars and the shedding of human blood. But since humanity has not yet discovered a milder method for the solution of these questions, it is better that great principles should be spread amidst the throes of wars, than that such principles should remain unrecognized, and that healthy progress should be unknown.

The great Martin Luther lived to see the commencement of those religious wars which were to determine whether the sway of the Roman religion should extend to the Baltic, or if the northern nations and princes Luther and Religious wars. Peace of Augsburg, 1555.would be allowed to profess a manlier creed. The greatest ruler of the times, Charles V. was bitterly against the Protestants, but the nobler principle triumphed, and Charles V. was compelled to grant toleration to the Lutherans in the peace of Augsburg in 1555, before he abdicated his throne.

His successor Philip II. of Spain renewed the war with increased fury and cruelty, and exhausted the vast resources of his empire in the two worlds to stamp out religious freedom. Holland and England made a noble stand for liberty. The Spanish Armada was sent in vain against the gallant islanders, and the Dutch under the immortal William of Orange Spanish Armada and Spain's war against Holland. Death of Philip II, 1598.maintained a long and arduous and unequal struggle, and triumphed in the end. The Protestant cause was safe in England and in Holland when Philip II. died in 1598.

But the bitter controversy was not yet set at rest. Twenty years after the death of Philip II., broke out what is known as the Thirty Years' War, a war which caused more slaughter, devastation and depopulation than any other European war of modern times. Germany and Austria, France and Spain, Denmark and Sweden, took share in this disastrous war, and Adolphus, Tilly and Wallenstein, Conde and Turenne were among the great captains. Religious toleration was once more secured by the peace Westphalia which terminated this war in 1648. The rural districts of Germany were depopulated, her commerce was destroyed Thirty Years' War and Peace of Westphalia, 1648.and her manufacture was ruined;—such are the sacrifices by which the Germans have secured their religious freedom. It was by such sacrifices that Englishmen were striving for political freedom under Cromwell during this very period.

The wars of Louis XIV. of France which began within twenty years after the peace of Westphalia were no doubt inspired by his ambition and lust of conquest, but a Wars of Louis XIV. His death, 1715.great principle was at stake in these wars too. The rise of absolute royal power in France threatened to engulf the new born liberties of modern nations, and Englishmen under William III. and under Queen Anne fought for the same cause in Europe for which they had striven at home under Cromwell. The noble cause triumphed once more, and Marlborough broke the French power. The last of these wars,—the war of the Spanish Succession,—was concluded by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, and Louis XIV. died two years after.

A period of peace, scarcely of one generation was vouchsafed to men, when another great question became ripe for decision. Was the Catholic power of Austria or the new born Protestant power of Prussia to be supreme in Germany? The question had been decided in England and in Holland in favour of the newer creed, and in France and in Spain in favour of the older one. In Germany, the home of the dispute, the question was yet undecided. Historians have waxed eloquent over the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War, (1740 to 1763,) Seven Years' War ending in 1763.in which all the great European powers were engaged, and in which red men in America and dark men in Asia took a share. Historians are never tired of painting the dignity, beauty and heroism of Maria Theresa, descendant of a long line of Austrian emperors, and the vigour, the determination, the indomitable energy of Frederick the Great, who was resolved to give to his native Prussia a place in the map of Europe. All this is very fine writing but we are liable in the midst of this word-painting to miss the truth. The great question which was ultimately decided by these wars was whether Protestant influence and power, or Catholic influence and power, should rule supreme in North Germany, from Holland to the frontier of Russia. The noble cause triumphed once more, and Prussia, representing the Protestant influence, became a power in Europe as against the declining power of Austria. Europe was then divided by a line which might be drawn across the map of the Continent; the free and rational Protestant religion remained supreme in the northern half; the more emotional Roman Catholic religion survived in the south. There were deeper reasons for this division than the mere vicissitudes of war. The northern nations of Europe, the Dolicho-Cephalic or long-headed Scandanavian races who are little susceptible to emotions, adopted the freer faith which afforded a greater scope for individual freedom and judgment; while the southern nations, the Bracho-Cephalic or broad-headed Gaelic or Celtic races who are naturally more emotional, clung to the ancient faith which afforded a higher scope for the development of our loftiest emotions and faith.

Young soldiers who fought the Seven Years' War were scarcely yet in their old age when another great question ripened for decision, and was decided in another sanguinary French Revolution and Waterloo, 1815.war or series of wars. The question was, whether the people should rule themselves, or be ruled by absolute kings and feudal lords. This question had been decided by Englishmen, for themselves, in the seventeenth century, between 1640 and 1688, but it came up for decision over a vaster area in Continental Europe a hundred years later. The French Revolution was the struggle of popular power against Toryism and absolute power in Europe. If France alone had been concerned in the matter, the question might have been decided without prolonged wars, as the events of the first years of the Revolution seemed to indicate. But Royal power all over Europe was interested in the issue, and Sovereigns in Vienna and Berlin trembled on their thrones, and made common cause with the French Sovereign and the fugitive French lords to crush the rising power of the people. And England, which had secured political freedom for herself, nevertheless allied herself with Austria and Prussia and Russia to uphold the cause of absolute Royal power in Europe? It is customary with historians to attribute the Napoleonic wars to the ambition of Napoleon, for the nations which fought against him are loth to admit their own blood-guiltiness. But Napoleon was the soldier of the Revolution and fought for the principles of the Revolution; his opponents were the champions of absolute Royal power, and strove to maintain it in Europe. As we have said before it is not given to humanity to solve such questions without wars. But be it remembered that in the dreadful wars of over twenty years ending at Waterloo, Napoleon was fighting for the right principle, the allied powers for the wrong.[1]

If Europe was not completely enslaved again after Waterloo, it was not the fault of the allied powers. It is both painful and amusing to read what they tried to do. They placed the worthless Bourbons again in France. They forced back Italy under the thraldom of Austria. They cut up Germany into its numerous petty estates, and seated on each throne its petty despot. They crushed Holland and Belgium into one kingdom. They forcibly annexed Norway to Sweden. And they handed over fifteen millions of the people of Poland back to Russia, Austria and Prussia!

The careful student will find in the history of Napoleon, whom the English minister Pitt rightly calls "the child and the champion of democracy," a repetition on a larger scale of the history of Cromwell. The one did for all Europe what the other did for England. Both began as earnest workers for the popular cause. Both were compelled to take all power into their own hands, because popular institutions do not grow in a day. Both failed in their immediate purpose; the Stuarts came back to England, and the Bourbons to France. But the cause which they strove for ultimately succeeded, in England 1688, in Europe between 1830 and 1860. Both Cromwell and Napoleon had their faults, but both were, in spite of their faults, great men and good men, who brought order out of chaos, and nobly advanced a good cause. But the Jacobites of England considered it a part of their loyalty to vilify the motives and character of Cromwell for well nigh two hundred years; and the historians of the nations which fought against Napoleon think it to this day a national duty to blacken his character and vilify his motives. And thus even the Commander-in-Chief of England, Lord Wolsley, who admits Napoleon to be "the greatest of all the great men," must nevertheless call him a "bad man."

The popular cause which the victors of Waterloo had tried to crush, triumphed in the end. France drove away her Bourbons who would learn nothing and had forgotten nothing. England secured an extension of popular power by the Reform Act of 1832, in spite of the Duke of Wellington, who after the most strenuous opposition to the measure, sullenly walked out of the House of Lords with a hundred other peers, when further opposition was unavailing! Belgium freed herself from the yoke of Holland and became a separate kingdom. Italy became united and independent after endless troubles through the endeavours of Mazzini, Cavour and Garibaldi. Norway secured for herself a free constitution after some struggle. The Hungarians too have secured freedom of internal administration after many disappointments and disasters. All Europe, except Poland, have reaped the benefits of the French Revolution.

Italy at last became free in 1860, and in February 1861, the first Italian Parliament assembled, and Victor Emanuel was proclaimed king of united Italy. A great question was thus solved, and the evil done by the victors of Waterloo was undone after nearly half a century. Five years after, the old question of the leadership of the Germanic nations ripened again for solution. The decision of the previous century required amendment. Frequent jealousies between Austria and Prussia pointed to the conclusion that there could be only one leader of the German nation, not two.

The war of 1866, ending in the battle of Sadowa, decided that the Northern and Protestant Austro-Prussian War and Sadowa, 1866.power was to be supreme not only in North Germany, but all over Germany. Prussia, under the genius of Bismark, made the most of this victory; all the Southern States which had taken arms against Prussia, like Bavaria and Würtemburg, had to pay heavily; while the States north of the Main which had taken arms against Prussia, like Hanover, Frankfort, and Nassau were summarily incorporated with Prussia! It was thus that the kingdom of Prussia increased in area and population in 1866, and the king of Prussia was thus befitted for a higher dignity, a few years later.

The principle of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 was the same as that of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. France tried to prevent Prussia from assuming the leadership of the Franco-Prussian War and Sedan, 1870.Germanic nations as Austria had done, and France failed as Austria had failed. The old question seems to be at last solved, and Bismark and Moltke have helped in the task of uniting Germany under the leadership of Prussia.

Twenty-two years have elapsed, and there has been no general European war since 1871. A new generation has sprung up in France and in Germany, and it is hoped that they have become accustomed to the new arrangement, and the causes which might lead to a fresh war are disappearing. But nevertheless one who travels in these frontier lands, and studies the question on the spot, is likely to entertain his doubts and suspicions. The German States like Frankfort United Germany.and Nassau (Wiesbaden), which have been incorporated with Prussia, feel the iron heel of the Prussian soldier, and bitterly hate him and fear him. The States south of the Main, like Bavaria and Würtemburg, which have not been incorporated with Prussia, but have simply submitted to her leadership, hate her with a still more genuine hatred. And the French provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, which have been forcibly annexed to Prussia, and more ardently and patriotically French now than they were in 1870, despite all loyal demonstrations which are skilfully got up to the contrary. But human foresight fails to penetrate the veil of the future, and can only darkly contemplate a new question which is ripening for solution, perhaps in more sanguinary wars than those of 1870 and 1871. May such wars be averted by the wisdom and moderation of nations.

FINIS.

- ↑ "The hostility of the European aristocracy caused the enthusiasm of Republican France to take a military direction, and forced that powerful nation into a course of policy which, however outrageous it might appear, was in reality one of necessity. Up to the treaty of Tilsit, the wars of France were essentially defensive; for the bloody contest that wasted the continent so many years was not a struggle for pre-eminence between ambitious powers, nor a dispute for some accession of territory, nor for the political ascendancy of one or other nation, but a deadly conflict to determine whether aristocracy or democracy should predominate; whether equality or privilege should henceforth be the principle of European governments." Napier's History of the Peninsular War.