The Colorado is one of the great rivers of North America. Formed in Southern Utah by the confluence of the Green and Grand, it intersects the northwestern corner of Arizona, and, becoming the eastern boundary of Nevada and California, flows outhward until it reaches tidewater in the Gulf of California, Mexico. It drains a territory of 300,000 square miles, and, traced back to the rise of its principal source, is 2,000 miles long. At two points, Needles and Yuma on the California boundary, it is crossed by a railroad. Elsewhere its course lies far from Caucasian Settlements and far from the routes of common travel, in the heart of a vast region fenced on the one hand by arid plains or deep forests and on the other by formidable mountains.

The early Spanish explorers first reported it to the civilized world in 1540, two separate expeditions becoming acquainted with the river for a comparatively short distance above its month, and another, journeying from the Moki Pueblos northwestward across the desert, obtaining the first view of the Big Canyon, failing in every effort to descend the canyon wall, and spying the river only from afar.

Again, in 1776, a Spanish priest traveling southward through Utah struck off from the Virgin River to the southeast and found a practicable crossing at a point that still bears the name “Vado de los Padres.”

For more than eighty years thereafter the Big Canyon remained unvisited except by the Indian, the Mormon herdsman, and the trapper, although the Sitgreaves expedition of 1851, journeying westward, struck the river about 150 miles above Yuma, and Lieutenant Whipple in 1854 made a survey for a practicable railroad route along the thirty-fifth parallel, where the Santa Fe Pacific has since been constructed.

The establishment of military posts in New Mexico and Utah having made desirable the use of a waterway for the cheap transportation of supplies, in 1857 the War Department dispatched an expedition in charge of Lieutenant Ives to explore the Colorado as far from its mouth as navigation should be found practicable. Ives ascended the river in a specially constructed steam-boat to the head of Black Canyon, a few miles below the confluence of the Virgin River in Nevada, where further navigation became impossible; then, returning to the Needles, he set off across the country toward the northeast. He reached the Big Canyon at Diamond Creek and at Cataract Creek in the spring of 1858, and from the latter point made a wide southward detour around the San Francisco Peaks, thence northeast to the Moki Pueblos, thence eastward to Fort Defiance, and so back to civilization

That is the history of the explorations of the Colorado up to forty years ago. Its exact course was unknown for many hundred miles, even its origin being a matter of conjecture. It was difficult to approach within a distance of two or three miles from the channel, while descent to the river’s edge could be hazarded only at wide intervals, inasmuch as it lay in an appalling fissure at the foot of seemingly impassable cliff terraces that led down from the bordering plateau; and to attempt its navigation was to court death. It was known in a general way that the entire channel between Nevada and Utah was of the same titanic character, reaching its culmination nearly midway in its course through Arizona,

In 1869 Maj. J. W. Powell undertook the exploration of the river with nine men and four boats, starting from Green River City, on the Green River, in Utah. The project met with the most urgent remonstrance from those who

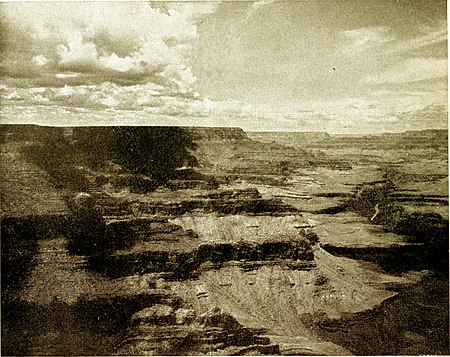

The Colorado, Foot of Bright Angel Trail.

Powell’s journal of the trip is a fascinating tale, written in a compact and modest style, which, in spite of its reticence, tells an epic story of purest heroism. It definitely established the scene of his exploration as the most wonderful geological and spectacular phenomenon known to mankind, and justified the name which had been bestowed upon it—The Grand Canyon—sublimest of gorges; Titan of chasms. Many scientists have since visited it, and, in the aggregate, a large number of unprofessional lovers of nature; but until a few years ago no adequate facilities were provided for the general sight-seer, and the world’s most stupendous panorama was known principally through report, by reason of the discomforts and difficulties of the trip, which deterred all except the most indefatigable enthusiasts. Even its geographical location is the subject of widespread misapprehension.

Its title has been pirated for application to relatively insignificant canyons in distant parts of the country, and thousands of tourists have been led to believe that they saw the Grand Canyon, when, in fact, they looked upon a totally different scene, between which and the real Grand Canyon there is no more comparison “than there is between the Alleghanies or Trosachs and the Himalayas.”

There is but one Grand Canyon. Nowhere in the world has its like been found.

The River and the Canyon Wall.

A canyon, truly, but not after the accepted type. An intricate system of canyons, rather, each subordinate to the river channel in the midst, which in its turn is subordinate to the whole effect, That river channel, the profoundest depth, and actually more than 6,000 feet below the point of view, is in seeming a rather insignificant trench, attracting the eye more by reason of its somber tone and mysterious suggestion than by any appreciable characteristic of a chasm, It is perhaps five miles distant in a straight line, and its uppermost rims are nearly 4,000 feet beneath the observer, whose measuring capacity is entirely inadequate to the demand made by such magnitudes. One can not believe the distance to be more than a mile as the crow flies, before descending the wall or attempting some other form of actual measurement.

Mere brain knowledge counts for little against the illusion under which the organ of vision is here doomed to labor. Yonder cliff, darkening from white to gray, yellow, and brown as your glance descends, is taller than the Washington Monument. The Auditorium in Chicago would not cover one-half its perpendicular span. Yet it does not greatly impress you. You idly toss a pebble toward it, and are surprised to note how far the missile falls short. By and by you will learn that it is a good half mile distant, and when you go down the trail you will gain an abiding sense of its real proportions. Yet, relatively, it is an unimportant detail of the scene. Were Vulcan to cast it bodily into the chasm directly beneath your feet, it would pass for a bowlder, if, indeed, it were discoverable to the unaided eve.

Yet the immediate chasm itself is only the first step of a long terrace that leads down to the innermost gorge and the river. Roll a heavy stone to the rim and let it go. It falls sheer the height of a church or an Eiffel Tower, according to the point selected for such pastime, and explodes like a bomb on a projecting ledge. If, happily, any considerable fragments remain, they bound onward like elastic balls, leaping in wild parabola from point to point, snapping trees like straws; bursting, crashing, thundering down the declivities until they make a last plunge over the brink of a void; and then there comes languidly up the cliff sides a faint, distant roar, and your bowlder that had withstood the buffets of centuries lies scattered as wide as Wycliffe’s ashes, although the final fragment has lodged only a little way, so to speak, below the rim. Such performances are frequently given in these amphitheaters without human aid, by the mere undermining of the rain, or perhaps it is here that Sisyphus rehearses his unending task. Often in the silence of night some tremendous fragment has been heard crashing from terrace to terrace with shocks like thunder peal.

The spectacle is so symmetrical, and so completely excludes the outside world and its accustomed standards, it is with difficulty one can acquire any notion of its immensity. Were it half as deep, half as broad, it would be no less bewildering, so utterly does it baffle human grasp.

Only by descending into the canyon may one arrive at anything like comprehension of its proportions, and the descent can not be too urgently commended to every visitor who is sufficiently robust to bear a reasonable amount of fatigue. There are four paths down the southern wall of the canyon in the granite gorge district—Mystic Spring, Bright Angel, Berry’s and Hance’s trails. The following account of a descent of the old Hance trail will serve to indicate the nature of such an experience to-day, except that the trip may now be safely made with greater comfort.

For the first two miles it is a sort of Jacob’s ladder, zigzagging at an unrelenting pitch. At the end of two miles a comparatively gentle slope is reached, known as the blue limestone level, some 2,500 feet below the rim, that is to say—for such figures have to be impressed objectively upon the mind—five times the height of St. Peter’s, the Pyramid of Cheops, or the Strasburg Cathedral; eight times the height of the Bartholdi Statue of Liberty; eleven times the height of Bunker Hill Monument. Looking back from this level the hugepicturesque towers that border the rim shrink to pigmies and seem to crown a perpendicular wall, unattainably far in the sky. Yet less than one-half the descent has been made.

Overshadowed by sandstone of chocolate hue the way grows gloomy and foreboding, and the gorge narrows, The traveler stops a moment beneath a slanting cliff 500 feet high, where there is an Indian grave and pottery scattered about. A gigantic niche has been worn in the face of this cavernous cliff, which, in recognition of its fancied Egyptian character, was named the Temple of Sett by the painter, Thomas Moran.

A little beyond this temple it becomes necessary to abandon the animals. The river is still a mile and a half distant. The way narrows now to a mere notch, where two wagons could barely pass, and the granite begins to tower gloomily overhead, for we have dropped below the sandstone and have entered the archæan—a frowning black rock, streaked, veined, and swirled with vivid red and white, smoothed and polished by the rivulet and beautiful as a mosaic. Obstacles are encountered in the form of steep, interposing crags, past which the brook has found a way, but over which the pedestrian must clamber. After these lesser difficulties come sheer descents, which at present are passed by the aid of rope

The last considerable drop is a 40-foot bit by the side of a pretty cascade, where there are just enough irregularities in the wall to give toe-hold. The narrowed cleft becomes exceedingly wayward in its course, turning abruptly to right and left, and working down into twilight depth. It is very still. At every turn one looks to see the embouchure upon the river, anticipating the sudden shock of the unintercepted roar of waters. When at last this is reached, over a final downward clamber, the traveler stands upon a sandy rift confronted by nearly vertical walls many hundred feet high, at whose base a black torrent pitches in a giddying onward slide that gives him momentarily the sensation of slipping into an abyss.

With so little labor may one come Lo the Colorado River in the heart of its most tremendous channel, and gaze upon a sight that here to fore has had fewer witnesses than have the wilds of Africa. Dwarfed by such prodigious mountain shores, which rise immediately from the water at an angle that would deny footing to a mountain sheep, it is not easy to estimate confidently the width and volume of the river. Choked by the stubborn granite at this point, its width is probably between 250 and 300 feet, its velocity fifteen miles an hour, and its volume and turmoil equal to the Whirlpool Rapids of Niagara. Its rise in time of heavy rain is rapid and appalling, for the walls shed almost instantly all the water that falls upon them. Drift is lodged in the crevices thirty feet overhead.

For only a few hundred yards is the tortuous stream visible, but its effect upon the senses is perhaps the greater for that reason. Issuing as from a mountain side, it slides with oily smoothness for a space and suddenly breaks into violent waves that comb back against the current and shoot unexpectedly here and there, while the volume sways tide-like from side to side, and long curling breakers form and hold their outline lengthwise of the shore, despite the seemingly irresistible velocity of the water. The river is laden with drift (huge tree trunks), witch it tosses like chips in its terrible play.

Standing upon that shore one can barely credit Powell's achievement, in spite of its absolute authenticity. Never was a more magnificent self-reliance displayed than by the man who not only undertook the passage of Colorado River but won his way. And after viewing a fraction of the scene at close range, one can not hold it to the discredit of three of his companions that they abandoned the undertaking not far below this point. The fact that those who persisted got through alive is hardly more astonishing than that any should have had the hardihood to persist. For it could not have been alone the privation, the infinite toil, the unending suspense in constant menace of death that assaulted their courage; these they had looked for; it was rather the unlifted gloom of those tartarean depths, the unspeakable horrors of an endless valley of the shadow of death, in which every step was irrevocable.

Returning to the spot where the animals were abandoned, camp is made for the night. Next morning the way is retraced. Not the most fervid pictures of a poet’s fancy could transcend the glories then revealed in the depths of the canyon; inky shadows, pale gildings of lofty spires, golden splendors of sun beating full on facades of red and yellow, obscurations of distant peaks by veils of transient shower, glimpses of white towers half drowned in purple haze, suffusions of rosy light blended in reflection from a hundred tinted walls. Caught up to exalted emotional heights the beholder becomes unmindful of fatigue. He mounts on wings. He drives the chariot of the sun.

Having returned to the plateau, it will be found that the descent into the canyon has bestowed a sense of intimacy that almost amounts to a mental grasp of the scene. The terrific deeps that part the walls of hundreds of castles and turrets of mountainous bulk may be approximately located in barely discernible pen-strokes of detail, and will be apprehended mainly through the memory of upward looks from the bottom, while towers and obstructions and yawning fissures that were deemed events of the trail will be wholly indistinguishable, although they are known to lie somewhere flat beneath the eye. The comparative insignificance of what are termed grand sights in other parts of the world is now clearly revealed. Twenty Yosemites might lie unperceived anywhere below. Niagara, that Mecca of marvel seekers, would not here possess the dignity of a trout stream. Your companion, standing at a short distance on the verge, is an insect to the eye.

Still, such particulars can not long hold the attention, for the panorama is the real overmastering charm. It is never twice the same. Although you think you have spelt out every temple and peak and escarpment, as the angle of sunlight changes there begins a ghostly advance of colossal forms from the farther side, and what you had taken to be the ultimate wall is seen to be made up of still other isolated sculptures, revealed now for the first time by silhouetting shadows. The scene incessantly changes, flushing and fading, advancing into crystalline clearness, retiring into slumberous haze.

Should it chance to have rained heavily in the night, next morning the canyon is completely filled with fog. As the sun mounts, the curtain of mist suddenly breaks into cloud fleeces, and while you gaze these fleeces rise and dissipate, leaving the canyon bare. At once around the bases of the lowest cliffs white puffs begin to appear, creating a scene of unparalleled beauty as their dazzling cumuli swell and rise and their number multiplies, until once more they overflow the rim, and it is as if you stood on some land’s end looking down upon a formless void. Then quickly comes the complete dissipation, and again the marshaling in the depths, the upward advance, the total suffusion and the speedy vanishing, repeated over and over until the warm walls have expelled their saturation.

Long may the visitor loiter upon the verge, powerless to shake loose from the charm, tirelessly intent upon the silent transformations until the sun is low in the west. Then the canyon sinks into mysterious purple shadow, the far Shinumo Altar is tipped with a golden ray, and against a leaden horizon the long line of the Echo Cliffs reflects a soft brilliance of indescribable beauty, a light that, elsewhere, surely never was on sea or land. Then darkness falls, and should there be a moon, the scene in part revives in silver light, a thousand spectral forms projected from inscrutable gloom; dreams of mountains, as in their sleep they brood on things eternal.