Translation:Dictionary of French Architecture from the 11th to 16th Century/Volume 1/Coat of arms

COAT OF ARMS

editWhen the Western armies precipitated in the East, with the conquest of Holy Sepulchre, their meeting formed such a mixture of different populations by the practices and the language, that it was well necessary to adopt certain signs made to recognize his people when coming from abroad to the battlefield with the enemy. The kings, constables, captains and even the simple knights who had some men under their control, in order to be able to be distinguished in the fray from enemies, whose costume was very similar, painted their shields ("écus") with bands of colors, so as to be identified from afar. Also, the oldest coat of arms are the simplest. As of 11th century, already the sport of the tournaments was extremely widespread in Germany, and the combatants adopted colors and emblems which they carried for as long as the contest; however, at that time, the noble jousters seemed to change currencies or signs and colors with each tournament. But when the shields with the coat of arms ("écus armoriés") had been tested in battle with the infidels, when, returned from the battle fields of the East, the Western Christians brought back with them these painted weapons, they had to preserve them as a memento of the event, as an honorable mark of their high deeds. From time immemorial, the men who faced dangers liked to preserve the dumb witnesses of their long sufferings, their efforts and their successes. The enamelled weapons of varied colors, of singular figures, carrying the trace of their engagements, were religiously suspended on the walls of the feudal castles; it was opposite them that the old lords told their adventures overseas to their children, who were accustomed to regard these shields as a family estate, a mark of honor and glory which was to be preserved and transmitted from generation to generation. Thus the coat of arms, painted initially to be recognized during combat, became hereditary like the name and the goods of the head of the household. Who doesn't remember seeing, after the wars of the [French] Revolution and the Empire, an old rusted rifle suspended on the mantelpiece of each thatched cottage?

When the coat of arms became hereditary, they had to be subjected to certain fixed laws, since they became titles of family. They had blasonner the weapons, i.e., to be explained 1. It was however only towards the end of the 12th century that the heraldry posed its first rules 2; during the 13th century it developed, and was fixed during the 16th and 15th centuries. Then the science of the blazon was strong in honor; it was like a language reserved for the nobility, of which it was jealous, and which it made a point of maintaining in its purity. The coat of arms had, during the 16th century, taken a great place in decoration, the fabrics, clothing; at this point in time the lords and people of their houses carried armoyés costumes. Froissart, in its chronicles, does not make appear noble of some importance without making follow its name of the blazon of its weapons. The novels of the 13th and 16th centuries, the official reports of festivals, of ceremonies, are filled with heraldic descriptions. We can in this article only give one summary outline of this science, although it is of a great utility to the architects who occupy themselves of archaeology. Fault of knowing the first elements of them, we saw our time to make blunders whose least disadvantage is to lend to the ridiculous one. It is a language which it should be abstained from speaking if it well is not known. Louvan Geliot; in its Index armorial (1635), known as with reason: "that the cognoissance of the" various species of coat of arms, and of the parts of which they are made up, "is so abtruse, and the terms if little usitez in the other subjects" of escrire, or speaking, that it takes several years to probe the bottom "of this abyme, and a long experiment to penetrate jusques in the heart" and in the center of this chaos." Since this author, the P. Menestrier particularly returned the study of this easier science; it is especially with him which we borrow the summary that we give here.

Three things must be used in the composition of the coat of arms: enamels, the shield or field, and figures. The enamels include: 1. metals which are: gold (“’’or’’”), or yellow; silver (“’’argent’’”), or white 2. the colors which are: “’’gueules’’”, which is red, azure, which is blue, “’’sinople’’”, which is green, “crimson”, which is deep-red purple, “’’sable’’”, which is black; 3. breakdowns or furs, which are: ermine and squirrel fur, to which one can add the counter-ermine (“’’erminés’’”) and the counter-vair. The enamels suitable for the ermine are silver or white for the field, and black for the mouchetures (1); opposite for the counterermine, i.e., black for the bottom, and silver or white for mouchetures 3. Squirrel fur is always of silver and blue, and is represented by the features indicated here (2). The counter-vair is also of silver and blue; it differs from squirrel fur in what, in the latter, metal is opposed to the color, while in the counter-vair metal is opposed to metal, and the color with the color (3). Squirrel fur from the “stake” or salaried is done by opposing the point of one squirrel fur to the base of the other (4).

Sometimes the ermine and squirrel fur adopt other colors that those which are clean for them; one says then ermine or vair of such or such enamel, for example: “Beaufremont” is called vair of silver and reds (5). A general rule of the blazon is not to put color on color at the reserve of the crimson, nor metal on metal; otherwise the coat of arms would be false, or at least to ‘’enquérir’’. One indicates by weapons to ‘’enquérir’’ those which leave the common rule, which is given for some remarkable act; in this case one can put color on color, metal on metal. The intention of that which takes similar weapons is to oblige to account for the reason which made him adopt them.

The shield or field is simple or made up; in the first case it has one enamel without divisions, in the second it can have several enamels. It then is divided or left. Four principal partitions are counted, from of which all the others derive: The party, which perpendicularly shares the shield in two equal parts (6); the half-compartment (7); the distinct one (8); cut (9). The party and the half-compartment form quartered (10), which is four, of six, eight, ten, sixteen districts and more still sometimes. Sliced and cut give quartered in saltire (11). The four partitions together give gironné (12). When gironné is of eight parts like the example (fig. 12), it simply is called gironné; but when there are more or less bosoms, one indicates the number of it: gironné of six, ten, twelve, fourteen parts. Tiercé is a shield which is divided into three equal parts of various enamels in accordance with each partition. Thus, tiercé by the party is called tiercé out of stake (13), X is called: tiercé out of stake of black, silver and azure; tiercé by the half-compartment is called tiercé in fasce (14), X is called: tiercé in fasce of azure, silver and reds; tiercé in band is given by the distinct one (15), X is called: tiercé in band of silver, reds and azure; tiercé bars some by cut (16), X is called: tiercé out of bar of azure, silver and reds. It moreover ploughed for the third time there which is not referred to the first four partitions, but which are traced according to certain heraldic figures. There is tiercé out of rafter (17), X is called: tiercé out of rafter of silver, reds and black; tiercé at a peak or mantel (18), X is called: tiercé at a peak or mantel of azure, silver and reds; tiercé in escutcheon (19), X is called: tiercé in escutcheon of reds, silver and azure; tiercé in pairle (20), X is called: tiercé in pairle of silver, black and reds; chappé (21), X is called: reds with three chappé silver silver stakes; fitted (22), X is called: fitted silver silver reds or stake; ambrassé with dextral and sinistral (23), X is called: of silver embraced with sinistral of reds; X is called: of silver embraced with dextral of reds; the vétu (24), X is called: of silver vêtu of azure; adextré (25), X is called: of adextré silver of azure; sénestré (26) X is called: of sénestré silver azure.

The position of the figures which are placed on the shield must be determined exactly, and to do it, it is necessary to know the various parts of the shield (27). A is the center of the shield; B the chief; D the dextral canton of the chief; E the sinistral canton of the chief; F the dextral side; G the sinistral side; C the point; H the dextral canton of the point; I the sinistral canton. When a figure alone occupies the center of the shield, his situation is not specified. If two, three or several figures are laid out in the direction of the letters D B E, they are said lines as a chief; if they are like the letters F A G, in fasce; if they follow the order of the letters H C I, at a peak; laid out like B A C, they are out of stake; like D A I, in band; like E A H, out of bar. Three figures are generally placed like the letters D E C: two and one; when they are placed like the letters H I B, they are said badly ordered. The figures posed as D E H I are indicated: two and two. Five figures posed like B A C F G, in cross; like D E A H I, in saltire; like D E A C, in pairle. Parts arranged like D B E G I C H F, in orle. A figure placed in A, in the medium of several others which would be different by their form, is in abyss. When one shield is not in charge of any figure one says: X is called of such metal or such color. The former counts de Gournai carried of full black. If the shield is charged only with one fur, one says: X is called “ermine” (fig. I). If it is in charge of figures, it is necessary to examine whether it is simple, i.e., without partitions, or if it is made up.

If it is simple, one states initially the field, then the principal figures and those which only accompany them or are secondary, then their number, their position and their enamels; the chief and the edge are indicated lastly like their figures. When the principal part encroaches on the chief or the edge, the chief or the edge must then be indicated before the principal part.

Old Vendôme (28) carried: of silver to the chief of reds to a lion of azure, armed, lampassé and crowned of silver stitching on the whole. If the shield is composed, one starts by stating divisions; if it is some more than four, one observes the number of lines which divide, and one says: “Left of, crossed by so-and-so much, which gives so many districts [areas]”. For example (29), known as: Started from one, crossed from two, which gives six districts; with the first of..., the second of..., the third, etc. (30). Started from three, crossed of one, which gives eight districts; with the first of..., the second of..., etc. (31). Started from two, crossed from three, which gives twelve districts; with the first of..., the second of..., etc One blasonne each district in detail, while starting with those of the chief, and while going from the right-hand side of the shield to the left.

The figures or ordinary parts of the blazon are of three kinds: 1. heraldic or clean figures; 2. natural figures; 3. artificial figures. The heraldic figures are subdivided in honourable parts of first and second order. The honourable parts of first order usually occupy in their width, when they are alone, one the third of the shield; except for the frank-quartier, canton and bosom which occupy only the fourth part of it.

These parts are: the chief (32), the fasce (33), the champagne (34), the stake (35), the band (36), the bar (37), the cross (38), the saltire (39); the rafter (40), the frank-quartier (41), the dextral or sinistral canton (42), the pile (43) or point it, the bosom (44), the pairle (45), the edge (46), the orle (47), narrower than the edge, the treschor (48) or essonier who differs from the orle only in what it narrower and is blossomed, the shield damages some (49), the bracket (50), seldom employed. When the parts from which we come to speak multiply, these repetitions name rebattements. Harcourt is called: “reds with two silver fasces” (51).

Aragon (kingdom) is called: of silver with four stakes of reds (52). Richelieu is called: of silver with three rafters of reds (53). The honourable parts, when they are not numbers some, must fill, as we said, one the third of the shield; but it happens sometimes that they have a less width, the third of their ordinary width or the ninth height or width of the shield, then they change name. The chief is nothing any more an but decreased chief, or roof. the decreased stake names small cane; the decreased fasce, currency; the decreased band, cotice; the decreased bar, crosses. The cotice and the cross-piece are reamed when they do not touch the edges of the shield. In this case, the cotice is known as stick perished in band, and stick perished out of bar crosses it. The champagne decreased is named flat. The fasces, the bands and the bars very-thin and put two to two are binoculars or gemelles (54). If they are laid out three to three, they are named third or thirds (55). The alesées fasces of these parts say hamade or hamaide (56).

When the shield is covered with stakes, fasces, bands, rafters, etc, in an equal number, i.e. so that one cannot say such enamel is the field, one blasonne as follows: pallé, fascé, bandaged, coticé, raftered, etc, of so many parts and such enamel. D' Amboise is called: pallé of silver and reds of six parts (57).

- If the number of pallés exceeds that of eight, one says vergetté.

- If the number of fascés exceeds eight, one says burellé, of so many parts; if bandaged that of nine exceeds, one says coticé.

- If the stakes, the fasces, the bands, the rafters are opposed, i.e. if these figures divided by a feature overlap so that metal is opposed to the color, and vice versa, one says then against-pallé, against-fascé, against-bandaged, against-senior.

- The less honourable parts, or of the second order, are:

- fixed. It is necessary to express if fixed is out of stake, band or fasce. X (58) is called: fixed in fasce of a point and two half of reds on silver.

- the équipollés points, which are always nine in chess-board. Bussi (59) is called: five points of silver équipollés at four points of azure.

- échiquetté (60), usually of five features; When there is less, one must specify it while blasonnant.

- the hooped one (61), which is bands and bars interlacing itself, six.

- treillized (62), which differs from hooped only because the bands and the bars are nailed with their meeting; enamel of the nails is expressed.

- rhombuses (63) and losangé (64) when the shield is filled with lozanges; of Craon is called: losange of silver and reds.

- the rockets or tapered, which differ from the rhombuses or losange only because the figures are lengthened; X (60) is called: of silver with five black rockets put out of stake to the of the same chief.

- the mâcles, which are rhombuses, openwork of smaller rhombuses; Rohan (66) is called: reds with nine silver mâcles.

- rustes or louts; who differ from the mâcles only in what the opening is circular; X (67) is called: reds with three silver rustes, 2 and 1.

- besants and oil cakes; the first are always of metal, the seconds of color; X (68) is called: of azure with six silver besants, 3, 2 and 1. The besants can be posed until the number of eight and either. The besants-oil cakes, which started from metal and color; X (69) is called: reds started from silver with three besants-oil cakes of the one in the other.

- the billets (70), which are small parallelograms posed upright. The billets can be reversed, i.e. posed on their large side; but it is expressed. They are sometimes bored in square or round; it is also expressed.

All the first order honourable parts have various attributes, or undergo certain modifications, of the following nomenclature: They can be lowered; of Ursins (71) is called: bandaged silver and reds of six parts, with the chief of silver, charged of an eel ondoyante of azure, lowered under another chief of silver, charged of a pink of reds; -- accompanied or surrounded, it is when around a principal part, as is the cross, the band, the saltire, etc,il has there several other parts in the cantons; X (72) is called: of black to the silver cross, accompanied by four billets of même; -- adextrées, which is placed at the dextral side of the shield; X (73) is called: of green with three adextrés silver clover of a cross of or; -- sharpened; X (74) is called: of silver

with the three sharpened stakes of azur; -- alèsées; Xintrailles (75) is called: of silver to the alesée cross of red (“’’gueules’’”); -- bandaged (fig. 71); barred it is called in the same direction as barred; bastillées it is called of a chief, a fasce, of a band, notched towards the point of the shield; X (76) is called: of azure to the chief of silver, bastillé of silver, three pièces; -- broadsides; X (77) is called: of azure to the silver band bordered of red; -- bourdonnées is said commonly furnished cross, at the end of its arms, buttons similar to bumblebees of pilgrims; - - bretessées. X (78) is called: of silver to the fasce of reds bretessées of two parts and two half; - - bretessées with doubles. X (79) is called: reds with the band bretessées with silver double; -- against-bretessées, X (80) is called: of silver to the bretessée fasce and against-bretessée sable; -- stitching says parts which pass on others; of Terrail

(81) is called: of azure to the chief of silver, charged with an issuant lion of reds, with the silver cotice stitching on the tout; -- cablées it is called of a made cross of cords or twisted cables; - - confined it is called when, in the four cantons which remain between the arms of a cross, there are parts posed in the field; -- charged it is called of all kinds of parts on which others are superimposed: thus the chief, the fasce, the stake, the band, the rafters, the crosses, the lions, the edges, etc, can be charged with besants, crescents, pinks, etc; X is called: of silver with three fasces of reds, charged each one with five saltires of argent; -- raftered it is called of a stake or any other part charged with rafters, and all the shield if it is filled by it; -- cléchée. Toulouse (82) is called: reds with the cléchées, emptied and pommetée cross of or; -- componées, X (83) is called: of azure to the componée band of silver and reds of five pièces; -- bent it is called of the chief when it is of metal on metal, or of color on color, as with the coat of arms of the town of Paris (one is also useful oneself of this word for the fasces, bands, rafters, of color on color, or metal on metal); - - studded. évêché of Hamin in Germany (84) is called: of azure to an bracket studded with sinistral, croisonnée and potencée with dextral of or; -- denchées, endenchées or toothed, X (85) is called: reds with the endenchée silver edge; Cossé de Brissac (86) is called: of black with three fasces denchées of silver. When the teeth are turned the point towards the top of the shield, it is expressed; variegated, X (87) is called: of azure to the fasce of silver variegated of reds; -- chequered, X (88) is called: of azure to the frank chequered district of silver and reds; -- engrélées, i.e., furnished with very-small teeth, X (89) is called: of azure to the engrélée cross of argent; -- entées, Rochechouart (90) is called: fascé, enté, ondé of silver and red; -- interlaced it is called of three crescents, three rings and other similar figures, posed the ones in the others; -- failed called broken rafters; of Oppède (91) is called: of azure with two failed silver rafters, the first with dextral, the second with sénestre; --florencées with a cross whose arms end in flowers of lily; -- gringolées are parts, such as the crosses, saltires, etc, finished by heads of snake; -- raised it is called when parts such as fasces, rafters, etc, occupy in the shield a place higher than that which is usually affected for them; - - moving are parts which seem to leave the chief, the angles, the sides or the point of the shield; - - heavy showers are parts, stakes, fasces, rafters, edges, etc, cut out in waves; -- resarcelées, bordered of a feature of another enamel; - - reprocessed are bands, stakes and fasces which; one of their, dimensioned, do not touch at the edge of the shield; - - vivrées, X (92) is called: of silver to the vivrée band of azure; - - emptied are up to date parts, through which one sees the field of the shield.

The crosses affect particular forms; they are said pattées, of Argentré (93) is called: of silver to the pattée cross of azure; - - recercelées, X (94) is called: of silver to the recercelée black cross; - - recroisettées, X (95) is called: of silver to the recroisettée black cross; - - anchored, X (95 1) is called: party of reds and silver to the cross moline of the one in the other; - - card-indexed, X (95 2) is called: of silver to the three driven black crosses, 2 and 1; - - bastonnées or clavelées, X (95 3) is called: of azure to a bastonnée cross of silver and silver, or with four let us bastons, two of silver and two of silver; -- from Lorraine, X (95 4) is called: of azure to the cross of Lorraine of silver; - - tréflées, X (95 5) is called: of silver to the tréflée cross of reds; - - gringolées, i.e. whose pilot wheels are finished by heads and blows of gringoles or guivres, X (95 6) is called: of silver to the cross of reds gringolée of black; - - anillées or nellées, i.e. whose pilot wheels finish out of irons of mills, X (95 7) is called: of silver to the nellée black cross. Écotées crosses, i.e. made up of two branches of tree whose branches are cut, heavy showers, hooped, vair, etc, finally in charge of the figures which charge the honourable parts.

The used natural figures in the blazon can be divided into five classes: 1. human figures, 2. animals, 3. plants, 4. stars and meteors, 5. elements, i.e. water, fire, ground. The human figures or of ordinary enamel of the blazon or are painted in complexion, with or without clothing, of natural and ombrées colors. One says: if these figures are vêtues and how, crowned, chevelées, ombrées, etc; one indicates their attitude, their gesture, which they carry and how.

The most used animals are, among the quadrupeds: the lion, the leopard, the wolf, the bull, the stag, the ram, the wild boar, the bear, the horse, the squirrel, the dog, the cat, the hare, etc; among the birds: the eagle, eaglets, the corbel, the merlettes, the swan, let us alérions them, the canetes, etc; among fish: the bar, the dolphin, the chub, the trout, etc; among the reptiles: the snake, the crocodile, the tortoise, the lizard; among the insects: flies, bees, horseflies; among the fantastic or allegorical animals: the winged siren, dragon, ampsystères or snakes, the griffon, the salamander, the unicorn, etc. The animals represented on the coat of arms usually look at the line of the shield; if they look at the left, they are said circumvented.

The lions and the leopards are the animals most usually employed, they have over all the others the privilége to be heraldic, i.e., that their form and their posture are subjected to fixed rules. The lion is always illustrated of profile: it is crawling, i.e., high on its legs of behind, the dextral leg of front raised, and the sinistral leg of behind behind; or passing, in other words léopardé, if it appears to go. The leopard always shows its mask of face, its usual posture is to be busy; if it crawls, it is said lionné or crawling.

The lion and the leopard have additional terms which are common for them; they are armed, lampassés, joined, are membrés, crowned, leaned, faced, circumvented, contrepassants, issuant, being born, mornés, defamed, burellés, bandaged, crossed, left, fascés, chequered, of ermine, squirrel fur. The armed lion are nails which can be of an enamel different from that of the remainder of the body; lampassé, of the language; morné, when it has neither language, neither teeth nor nails; defamed, when it does not have a tail. Olivier de Clisson, constable of France under Charles VI, carried: reds with the silver lion armed, lampassé and crowned of silver, etc.

During the XIII E, 16th and 15th centuries, the heraldic animals were illustrated according to certain forms of convention which it is necessary to know well, because it is not without reason that they had been adopted. The various figures which cover the shield being generally intended to be seen by far, it was necessary that their form very-was accentuated. The artists of these times had included/understood it; if the members of the animals are not well detached, if their movement is not exaggerated, if their aspect is not perfectly distinct, at a certain distance these figures lose their particular character, and present nothing any more but one confused spot. Since the XVI E century the decorative drawing was softened, and the heraldic figures lost this character which easily made them recognize. One wanted to give to the animals a more real aspect, and as the heraldry is an art purely of convention, this attempt was contrary with its principle. It is thus of great importance to penetrate itself of the traditional forms given to the animals as with all the other figures, when it is a question of painting coat of arms. Although we cannot in this summary give too many examples, we will however try to join together some types which will make include how much one deviated, in the last centuries, of the forms which had not been adopted without cause, and how much it is useful to know them: because, in all the armoriaux ones printed since the Rebirth, these types were each day increasingly disfigured; it is at most if in the last works which treat EC matter one finds some vestiges of a drawing which had not had to suffer from deterioration, since the coat of arms are signs whose principal merit is to perpetuate a tradition. It is especially in the monuments of the 16th century that we will seek these types, because it is during this century that the heraldry adopted figures whose quite distinct characters were reproduced without modifications sensitive until the moment when the artists, accustomed to a vulgar imitation of nature, did not include any more the fundamental laws of the decoration applied to the monuments, the pieces of furniture, with the weapons, with clothing. Here thus some of these figures:

We will start with the crawling lion (96); With, crowned. Passer by or léopardé (97).

Issant (98).

The leopard (99).

The wolf passing (100); charming, when it is posed on its hind legs.

The stag (101).

The wild boar (102).

The éployée eagle (103).

With the lowered flight (103 bis).

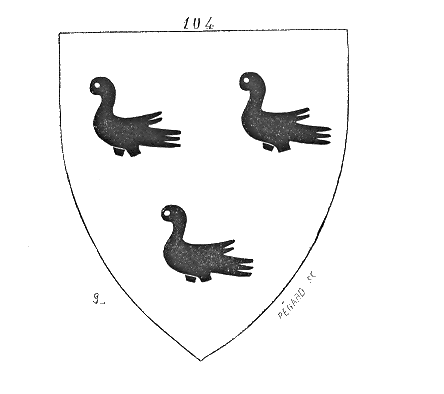

Les merlettes (104).

Les alérions (105).

The bar (106).

The dolphin (107).

Le chabot (108).

La syrène (109).

The dragon (110).

The griffon (111).

The plants, trees, flowers, fruits are often employed in the coat of arms. If they are trees, one indicates them by their name. Nogaret is called: from silver to the torn off green walnut tree, i.e. of which the roots are visible and are detached at once from the shield.

Some trees are illustrated in a conventional way. Créqui (112) is called: of silver to the créquier of reds. One indicates by chicot tree trunks cut, without sheets. When sheets are posed at once, one indicates the number and the species of it.

It is the same for the fruits. The hazel nuts in their envelope are said, in blazon, coquerelles. The flowers are indicated by the number of their sheets, clover, quad-sheets, cinquefoils. All kinds of flowers are employed in the coat of arms; however one hardly meets before the 15th century that the pinks, the poppy, the clover, the quad and cinquefoils and the flower of lily 4. By indicating the species and the number of the flowers or fruits in the shield, one must also indicate if they are accompanied by sheets, one says them then broken into leaf; if they hang with a branch, one them known as constant. The fruits which one generally meets in the old coat of arms are: apples, pine cones, grapes, nipples, the coquerelles ones. The quad and cinquefoils are bored by the medium of a round hole, which lets see the field of the shield. The pink it is called buttoned when its heart is not same enamel as the flower. Among the stars, those which are in the past employed are the sun, the stars and the crescent; the sun is always silver. When it is of color, it takes the name of sun shade. The position of the crescent is to be rising, i.e. its horns are turned towards the chief of the shield. When its horns look at the point of the shield, one it known as versed; turned when they look at the dextral side; circumvented if they look at the sinistral side. One still says crescents in a number, and according to their position, which they are turned in band, are leaned, sharpened, faced, badly ordered. The star is usually of five points; if there is more, it should be specified while blasonnant. X is called: reds with three stars of eight silver lines, 2 and 1. The rainbow is always painted with the naturalness, in fasce, slightly curved.

The elements, which are fire, the ground and water, are presented in various forms: fire is flame, lit torch, burning torches, coals; the ground is illustrated in the form of mounts, rocks, terraces; water in the form of waves, of sources, rivers.

The artificial figures which enter the coat of arms are: 1. instruments of crowned or profane ceremonies; 2. vulgar clothing or ustensils; 3. weapons of war, hunting; 4. buildings, turns, cities, castles, bridges, doors, gallées, naves or naves (galères and ships), etc; 5. instruments of arts or the trades. It is necessary, according to the ordinary method, to indicate these various objects by their names while blasonnant, to mark their situation, their number and enamels of the various attributes which they can receive. Lily (113) is called: of azure to a silver sword out of stake the point in top, surmounted by a crown and accosted of two flowers of of the same lily.

Among the weapons most usually illustrated in the old coat of arms, one distinguishes the swords, the badelaires (short, broad and bent swords), the arrows, the lances, the axes, the masses, the clamps. spurs, serrated rollers of spurs, heaumes, horns, huchets, spears, snares, etc.

The castles are sometimes surmounted turrets, one says them then summoned of so much; they are said built…, when the stone joints are indicated by a different enamel. The kingdom of Castille (114) is called: reds, with the summoned of three turns of silver, built, openwork castle of azure. The surmounted towers of a turret are called donjonnées. If the turns do not have keeps, but only one notched crowning, one must say crenelated of so many parts.

Openwork is used when the doors or windows of the turns or castles are of an enamel different from the building. The same terms apply to the other buildings. Dried it is called of a building whose roof is of another enamel.

A ship hooped, is equipped, when it is provided with all its tackles and veils. Paris (115) is called: reds with the hooped nave, equipped with floating silver on of the same waves, with the bent chief of France old. If the ship is without masts and veils, one says: stopped ship. When the anchors are painted various enamels, one must specify it. The trabe is the cross-piece, the stangue it is the stem, the gumenes are the cables which attach the anchor.

We will not go into further details concerning the various instruments or buildings which appear in the coat of arms; we return our readers to the special treaties.

Crack, in terms of blazon, is a change which one subjects the coat of arms to distinguish the branches from the same family. One broke in the origin only by the change of all the parts, by preserving only enamels. Thus the counts de Vermandois, left the house of France, carried: chequered of silver and azure, with the chief of France. Later one broke by changing enamels and preserving the parts. The branch elder of Mailli is called: of silver with three green mallets; Mailli of Burgundy carry: reds with three silver mallets: other branches carry: of silver to the mallets of black, silver with three mallets of azure. One also broke by changing the situation of the parts, or by cutting off some from the parts. But the manner of breaking which was most ordinary in France consisted in adding a new part to the coat of arms full with the family. As of the end of the 13th century the princes of the blood of the house of France broke this manner, and one chooses as crack of the parts which did not deteriorate the principal blazon, such as the lambel; Orleans is called: from France to the lambel with three hanging of silver for crack; - - the edge, Anjou is called: from France to the edge of reds; - - the stick peri, Bourbon is called: from France to the stick peri in band of reds; - - the canton, the serrated roller of spur, the crescent, the star, it besant, the shell, the small cross, the third quad or fifth breaks into leaf. One still breaks by quartering the weapons of his house with the weapons of a family in whom one took alliance.

In the examples which we gave, we chose for the shields the form generally adopted during the XIII E, 16th and 15th centuries 5,form who was modified during the XVI E and XVII E centuries; one then gave them a contour less acute and often finished with the point in accodance.

The married women carry shields coupled; the first escutcheon gives the weapons of the husband, and the second theirs. For the shields of the girls, one adopted, as of the 16th century, the form of a rhombus.

Additional figures accompany the armoyés shields. From the end of the 16th century, one frequently sees the shields supported by supports and holding, overcome sometimes cimiers, stamps, and being detached on lambrequins.

The support is a tree, to which the shield is suspended; holding are one or two figures of men-at-arms, knights, forks and spoons of their armours and the coat armoyée with the weapons of the shield. The origin in this manner of accompanying the shield is in the tombs of the 13th and 16th centuries. In the church of the abbey of Maubuisson, in front of the furnace bridge of Michel saint, one saw, at the end of last century, the tomb of Clarembaud de Vendel, on which this character was represented vêtu of a coat of mail with his shield placed on the body, émanché of four parts. There still exists in the crypts of the church of Saint-Denis a rather great number of statues of princes of royal blood, died at the end of the 13th century or the beginning of the XIV E, which are represented same manner, slept on their tombs. We will quote inter alia that of Robert de France, count de Clermont, lord of Bourbon (coming from the Jacobins of Paris), having his shield hung in shoulder-belt tilted on the left side, bearing: from France (old) to the cotice of reds; that of Louis de Bourbon, grandson of Louis saint, in the same way; that of Charles d' Alençon of which the shield is called: from France (old) to the edge of reds charged with sixteen besants of..., etc (see: TOMB). In the silver sums of silver, Philippe de Valois is represented sitting on a folding stool, holding his high sword of the right hand and the left being based on the shield of France. In the noble ones in the noble pink and the Henri of England, this prince is illustrated upright in a ship which it leaves to half-length, holding in his right-hand side a high sword and his left one shield quartered of France and England. In the Cherubs the shield is attached to a cross which holds place of mast with the vessel. Taking the part for the whole, one gave soon to these silver currencies the name of shields of silver.

It is still a way of holding, it is that which consists in making carry the shield by mores, savages, sirens, real or fabulous animals. The origin of this use is in the tournaments. The knights made carry their lances, heaumes and shields by pages and servants disguised as strange characters or animals. To open the step of weapons holding them of the tournament made attach their shields to trees on main road, or in certain assigned places, so that those which would like to fight against them were going to touch these shields. To keep them one put dwarves, giants, mores, men disguised in monsters or wild beasts; one or more heralds took the names of those which touched the shields of holding. With the famous tournament which took place in 1346, the first from May, in Chambéry, Amédée VI of Savoy made attach its shield to a tree, and made it keep by two large lions, which since this time became holding them of the coat of arms of Savoy; this prince chooses probablemeut these animals for holding, because Chablais and the duchy of Aoste, its two principal seigniories, had lions for coat of arms. The armoyés shields, stamps, cimiers and currencies of the knights who appeared in this tournament, remained deposited twenty during three centuries in the large church of the fathers of Saint-François in Chambéry; it was only in approximately 1660 that the good fathers, while making whitewash their church, removed this invaluable monument.

Charles VI appears to be the first of kings de France which made carry its shield and its currency by holding. Juvénal of Ursins tells that this prince, energy with Senlis to drive out, continued a stag which had with the neck a gilded copper chain; it wanted that this stag was taken with the lakes without killing it, which was carried out, "and found one that it avoit with the collar the aforementioned chain where avoit" written: Cæsar hoc mihi donavit. And consequently, the roy, of its movement, "carried in currency the crowned silver kite to the collar, and everywhere where one" mettoit his weapons, y avoit two stags holding its weapons on a side and "the other. 1380." Since, Charles VII, Louis XI and Charles VIII, preserved the winged stags as holding of the royal weapons. Louis XII and François I er took for holding, the first, of the pigs-épics, the second, of the salamanders, which were the animals of their currencies. From the XVI E century, almost all the families of the French nobility adopted holding for their coat of arms; but this use did not have anything rigorous, and one often changed, according to the circumstances, the supports or holding of his weapons. Such family, which had for holding of her escutcheon of the savages or the mores, making it paint in a vault, changed these profane figures against angels. The weapons of Savoye, for example, about which we spoke, were supported by an angel on one of the doors of the convent of Saint-François in Chambéry, with this currency: The crux fidelis inter omnes. The coat of arms of the cities were also, starting from the 15th century, represented with supports: Basle has as a support a dragon; Bordeaux two rams; Avignon two gerfauts, with this currency: Unguibus and rostro. Often the supports were given by the name of the families; thus the house of Ursins had two bears for supports. The supports are sometimes varied; the kings of England have as supports of their weapons, on the right, a leopard crowned armed and lampassé with azure, on the left, a silver unicorn coupled of a crown and attached to a silver chain passing between the two feet of front and turning over on the back. But these supports are posterior with the meeting of Scotland to the kingdom of England; before this time, the supports of the weapons of England were a lion and a dragon, this last symbol because about the Jumper dedicated to George saint.

During the tournaments and before the entry in string, it was of use to expose the coat of arms of the combatants on rich person carpet. Perhaps this is there the origin of the lambrequins on which, starting from the 15th century, one painted the coat of arms. When one holding was presented at the step of weapons, its shield or its targe, in certain circumstances, was suspended in a house which had to be opened to make it touch by those which were made register for jouter. "the first samedy of the month of may the year 1450, the house was tended, like it estoit habit, and as always continued each one samedy of the year, during the influence of the susdicts. If came audict house a young person escuyer from Burgundy, named Gerard de Rossillon, beautiful compaignon, high and right, and of beautiful size; and adreça ledict escuyer in Charolois the herald, luy applicant that it luy fist opening; because it vouloit to touch the white targe, in intention of combatre the knight contractor of the axe, jusques with the achievement of twenty-five blows. Ledict herald luy fist opening, and ledict Gerard touched: and the EC was faict the report/ratio with lord Jacques de Lalain, who nimbly sent towards luy to take day... 6 "One can still see in this use the origin of the lambrequins which seem to discover the shield. It is necessary to also say that as of the 15th century the heaumes of the knights who owed jouter were armed with a gilded and painted leather or fabric lambrequin, shredded on the edges; this kind of ornament which accompanies the stamp surmounting the shield, and which falls on the two sides, appears to be the principle of this accessory which one finds joint with the coat of arms during the 15th and XVI E centuries... "the tymbre doibt estre on a leather boully part, which doibt estre well faultrée of ung doy of espez, or more by inside; and doibt to contain the aforementioned leather part all the top of the heaulme, and will be covered the aforementioned part of the lambequin, armoyé of the weapons of cellui which will carry it. And on the aforementioned lambequin, with the more hault of the top, will have sat the aforementioned tymbre, and around icellui will have ung torsel of the colors which the aforementioned tournoyor will vouldra, of large arm or more or less with its pleasure 7." We already said it at the beginning of this article, the knights and princes who presented themselves in the string for jouter adopted weapons of imagination and appeared with their hereditary weapons only exceptionally. One took too much with serious the coat of arms of family to deliver them to the chances combat which were only one play. It is curious to read on this subject the passage of the Memories of Olivier of Walk, strong expert in these matters. In addition, he says 8,presented Michau of Some on a covered horse of his weapons: whose several people were filled with wonder; and sembloit with several, that considered that the weapons of a noble man are and doyvent estre the enamel and the noble mark of its old nobility, that by no means does not have itself to endanger stumbled estre, reversed, abatue, pressed so low only with ground, as long as the noble man can divert it or deffendre: because to venture the rich person monster of his weapons, the man ventures more than his honor, for what to venture its honor only it his is despense, and this where each one has to be able; but to venture its weapons, it is put in avanture the ornament of its parens and its chalk-lining, and avanturé at small price this where it can have only the quantity of its share; and in that manner is put at the mercy of a horse and an irrational beste (which can estre carried to ground by a hard attack, or choper at by soy or mémarcher); what more the valiant knight and more sor society man ressongue well, and doubts to carry on its back in such case... "

The day before of the tournament the tournoyeurs were invited to make deposit their weapons, heaumes, stamps and banners with the hotel of the judges tellers. These weapons, deposited under the gantries of the court, were examined by the judges to make the department of it. "Item, and as all the heaulmes will be thus put and order to separate them, will come all the injuries and damoiselles and all lords, knights and escuiers, by visiting them of ung end to other, there présens the judges who will maineront troys or four turns the injuries for veoir well and visiting the stamps and will have there ung hérault or prosshieldtor which will say to the injuries, according to the place where they will be, the name of ceulx with which are the stamps, AD what if there is of it no one which has injuries mesdit, and they touch its stamp, which it is the following day for recommended. Null Touteffoiz doibt estre batu to that the tournoy, not by the advis and schedules judges, and the case well desbatu and attaint with the vray, estre found such as it deserves pugnicion; and at the time in this case doibt estre so well batu mesdisant it, and that its shoulders smell très-bien it, and by manner that a autreffois does not speak or médie thus deshonnestement about the injuries, like it has accustomed 9."

These stamps, which one surmounted the armoyés escutcheons, were not, like the supports and holding, which variable accessories during the course of the 15th century. Noble which had jouté in a brilliant way during the duration of a tournament, the covered head of a heaume stamped some singular emblem, and under the name of knight of the unicorn, of the dragon, etc, stamped of this heaume the shield of the weapons of its family, during a certain time, or its life during, if new prowesses did not make forget the first. It was only at the end of the 15th century that one adopted for the stamps, as for the crowns, of the forms which indicated the degree of nobility or the titles of noble (see: LAMBREQUIN, STAMP). It is only to the XVII E century that the weapons of France were covered and wrapped of a house or tries, i.e. of a baldachin and two curtains, this support or wraps being since then reserved for the emperors and kings. Here how these weapons were blasonnaient: of azure with three flowers of lily of silver, two and one, the shield surrounded of the collars of the orders of the Michaelmas and the Holy Spirit, stamped of an entirely opened helmet, silver; over, the crown closed with imperial of eight rays, highly raised of a double flower of silver lily, which is the cimier; for holding, two angels vêtus of the coat of arms of France; the covered whole of the royal house sown of France, doubled ermine, and for currency: "Lilia not laborant, neque nent." Under Henri IV and Louis XIII, the shield of Navarre was coupled with that of France, and one of the angels was vêtu coat of arms of Navarre. To Charles V, the flowers of lily were without a number on field of azure; it was this prince who reduced their number to three in the honor of the Holy Trinity. Since the XVII E century, the dukes and pars wrapped their weapons of the house, but with only one curtain. The origin of this envelope is, as we saw higher, the house in which the tournoyeurs withdrew themselves before or after the entry in string, and not not the imperial, royal or ducal coat; it is thus a misconception to place the crown above the house, the house should on the contrary cover the crown; and, indeed, in the first weapons painted with the house, the crown is posed on the shield, and the house wraps the whole. This error, that we see remaining, indicates how much it is essential, in fact of coat of arms, to know the origins of all the principal parts or accessories which must compose them.

The regular clergy and sshieldlar, like feudal lord, adopted weapons as of the 13th century; i.e. the abbeys, the chapters, évêchés had their weapons; what did not prevent the bishops from carrying their hereditary weapons. Those, to distinguish their escutcheons from those of the sshieldlar members of their family, surmounted them episcopal hat or mitre, whereas the nobility did not pose any sign above its weapons. We saw keystones, paintings of the 13th and 16th centuries, where the escutcheons of the bishops are surmounted hat or mitre 10. The episcopal hat and the cardinal's hat have the same form; only first is green and has only ten nipples with the cords on each side, posed 1, 2, 3 and 4; while second is red and the finished cords each one by fifteen nipples, posed 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

As of the 13th century painted or carved decoration admitted in the buildings a great number of heraldic figures, and the coat of arms exerted an influence on the artists until the beginning of the XVI E century. Monumental painting hardly employs, during the XIII E, 16th and 15th centuries, that the heraldic enamels; it does not model its ornaments, but, as in the blazon, the layer flat by redrawing them by a black feature. The harmonies of heraldic painting are found everywhere during these times. We develop these observations in the word PAINTING, to which we return our readers.

A great number of stained glasses of the time of Louis saint have for edge and even as funds of the flowers of lily, of the turns of Castille. In Our-injury of Paris two of the gates of the frontage presented in their bases of the flowers of lily engraved in hollow. It is the same with the gate for the church for Saint-Jean-des-Vignes with Soissons. The central pier of the principal door of the church of Semur in Auxois, which dates from first half of the 13th century, is covered with the weapons of Burgundy and flowers of lily carved in relief. In Rheims, in Chartres, the stained glasses of the cathedrals are filled with flowers of lily To the cathedral of Troyes one meets in the stained glasses of the 16th century the weapons of the bishops, those of Champagne. The same cities and corporations took also coat of arms; the good cities, those which were more particularly associated with the efforts of the royal capacity to be freed from feudality, had the right to place as a chief the weapons of France; such were the weapons of Paris, of Amiens, of Narbonne, Turns, Holy, of Lyon, of Béziers, of Toulouse, of Uzès, of Castrate, etc. Some same cities carried: from France, particularly in Languedoc. The corporations generally took for weapons figures drawn from the trades which they exerted; it was the same for the middle-class men annoblis. In Picardy much of coat of arms of the 15th and XVI E centuries are rebuses or speaking weapons, but the majority of these weapons belonged to families left the industrial and commercial class of this province.

It was at the end of the 13th century, under Philippe the Bold one, whom the first letters of nobility in favour of a orfévre named appeared Raoul (1270) 11. Since then the kings of France used largely of their prerogative; but they could not make that the former nobility of extraction regarded these new annoblis as gentilhommes. The coat of arms of the new nobility, either made up with the camp, opposite the enemy, but by some herald in the content of his cabinet, do not have this originality of aspect, this clearness and this frankness in the distribution from enamels and the figures which we find in the coat of arms of the former nobility.

At the beginning of his reign, Louis XV still increases on his predecessors by instituting the military Nobility 12. Considering which precedes the this edict still indicate cares towards the nobility of race, and the tendencies of monarchy, from now on main of feudality. "the great examples of zeal and courage that the Nobility of our Roïaume gave during the course of the last war, say these considering, were followed so with dignity by those which did not have the same advantages on the side of the birth, that we will never lose the memory of the generous emulation with which saw we them fighting and overcoming our enemies: we already gave them authentic testimonys of our satisfaction, by the ranks, the honors and the other rewards that we granted to them; but we considered that these thanks, personal to those which obtained them, will die out one day with them, and nothing appeared more worthy to us of the kindness of the Sovereign than to make pass until the distinctions than they so precisely acquired by their services. The oldest Nobility of our States, which owes its first origin with the glory of the weapons, will undoubtedly see with pleasure that we look at the communication of its Privileges as the most flattering price which those can obtain which went on its traces during the war. Already annoblis by their actions, they have the merit of the Nobility, if they do not have yet the title of it; and we all the more readily go to theirs to grant, which we will compensate by this means for what could miss with the perfection preceding laws, by establishing in our Roïaume a Military Nobility which can be acquired of right by the weapons, without particular letters of annoblissement. The King Henry IV had had the same object in article XXV of the edict on the sizes, that it gave in 1600... "

The institution of the military orders had created to the 12th century of the enough powerful brotherhoods to alarm the kings of Christendom. It was feudality, either rival and disseminated, but organized, armed and being able to dictate the hardest conditions with the sovereigns. The monarchical capacity, after having broken the beam, wanted to connect it around him and to be made a rampart of it; it instituted during the 15th and XVI E centuries the orders of the Michaelmas and the Holy Spirit, during the XVII E the order of Saint-Louis, and later still Louis XV establishes the order of the Deserve-Soldier little time after the promulgation of the edict of which we quoted an extract. These institutions erased the last armoyés escutcheons. From now on the nobility was to be recognized by a general sign, either by individual signs. Monarchy tended to put on the same row, to cover same coat, any nobility, which it was old or new, and the night of August 4, 1789 saw breaking, by the constituent assembly, of the escutcheons which, veiled by the royal capacity, were for crowd only the unjust sign of priviléges, either the memory and the mark of immense services rendered to the fatherland. The royal escutcheon of Louis XIV had covered all those of the French nobility; at the day of the danger it was only; it was broken; that was to be.

1 : Blasonner vient du mot allemand blasen (sonner du cor): «C'était autrefois la «coutume de ceux qui se présentaient pour entrer en lice dans les tournois, de «notifier ainsi leur arrivée; ensuite les hérauts sonnaient de la trompette, blasonnaient «les armes des chevaliers, les décrivaient à haute voix, et se répandaient «quelquefois en éloges au sujet de ces guerriers.» (Nouv. Méth. du blason, ou l'art hérald. du P. Ménestrier, mise dans un meill. ordre, etc., par M. L***. In-8°, Lyon, 1770.)

2 : «Louis le Jeune est le premier de nos rois qui soit représenté avec des fleurs «de lys à la main et sur sa couronne. Lorsqu'il fit couronner son fils, il voulut que «la dalmatique et les bottines du jeune prince fussent de couleur d'azur et semées de «fleurs de lys d'or.» (Ibid.)

3 : Il est entendu que, conformément à la méthode employée depuis le XVIIe siècle pour faire reconnaître par la gravure les émaux des armoiries, nous exprimons l'argent par l'absence de toute hachure, l'or par un pointillé, l'azur par des hachures horizontales, red par des hachures verticales, le green par des hachures diagonales de droite à gauche (de l'écu), le pourpre par des lignes diagonales de gauche à droite, le sable par du noir sans travail, bien que dans la gravure en taille-douce ou l'intaille, on l'indique par des hachures horizontales et verlicales croisées.

4 : Voyez le mot FLEUR DE LIS.

5 : Il ne paraît pas que des règles fixes aient été adoptées pendant les XIIIe et XVIe siècles pour la forme ou la proportion à donner aux écus, ils sont plus ou moins longs par rapport à leur largeur ou plus ou moins carrés; il en existe au XIIIe siècle (dans les peintures de l'église des Jacobins d'Agen, par exemple) qui sont terminés à la pointe en demi-cercle.

6 : Mémoire d'Olivier de la Marche. liv. I, chap, XXI.

7 : Traicté le la forme et devis d'ung tournoy. Les mants du livre des tournois par le roi Réné. Bib. imp. {Voir celui n°8351).

8 : Liv. I, char. XXI.

9 : Traicté de la forme et dev. d'ung tournoy, Bib. imp. man. 8351; et les Œuvres chois. du roi Réné, par M. le comte de Qnatrebarbes. Angers, 1835.

10 : A Vézelay, XIIIe siècle; dans la cathédrale de Carcassonne, XIVe siècle, etc.

11 : Le présid. Hénault, Abrégé chron. de l'Histoire de France.

12 : Édit du mois de novembre 1750.

Source text

editDictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle - Tome 1, Armoirie