Voyage in Search of La Pérouse/Volume 2/Chapter 13

CHAP. XIII.

10th April.

About seven in the morning we got under way, with a pretty fresh breeze from the east-south-east, and steered for an hour from north-west by south to north, and afterward north by east, passing out through a channel toward the north of our anchoring place, which had been examined by Citizen Legrand.

In this channel we found by the lead from five fathoms and a half to nine fathoms water.

Some of the natives followed us in their canoes, expressing great regret at our quitting their island. They cried out from all parts, offa, offa Palançois, at the same time giving us marks of their regard.

We soon got ahead of the canoes that were paddled along; but those with sails were obliged to slacken their rate of going, to keep at a short distance from us; and we had an opportunity of observing, that they would have taken the lead of our vessels considerably, if they had availed themselves of the whole force of the breeze: this advantage, however, they would soon have lost, if the wind had been stronger, and the water less smooth. As soon as we got into the open sea, they desisted from keeping us company any farther. We were then more than two leagues from the anchoring place we had just quitted, and we set the west end of Attata, bearing south 48° west.

At this time we had a gravelly bottom, with twenty-two fathoms and a half of water.

11th. The next day, about five in the afternoon, we made Tortoise Island, bearing from us north-west by north.

On the 16th, about seven o'clock in the evening, the Esperance made a signal for seeing land west 18° north, about eight leagues' distance. This was Erronan, the easternmost of the islands of the archipelago of Espiritu Santo, discovered by Quiros in 1606. A little before noon the island of Annaton was in sight, distant ten leagues, south west by south.

It was five in the afternoon when we made the island of Tanna, bearing west 16° north. Pillars of smoke issued from its volcano, and spread abroad in the air, forming clouds, which rose at first to a prodigious height, and which, after having traversed an immense space, sunk lower as they grew cooler. During the night we enjoyed the brilliant spectacle of these clouds, illumined by the vivid light of the burning matter, which was thrown out from the bowels of the volcano at intervals.

18th. We were steering westerly, the wind blowing very fresh from the east, when, about half after three in the morning, Dumérite, the officer on the watch, heard the screams of a flock of sea-fowl passing very close by our ship: apprehensive that we were near some of the rocks, which commonly serve them as a retreat, he thought it advisable to bring to, and wait for day-light to continue our course: and as soon as day broke, we saw a very little way to leeward of us some reefs of rocks stretching a great way, on which our ship must inevitably have struck, if this fortuitous occurrence had not given us notice to stop our course in time. In fact, as the night was extremely dark, it would have been impossible to have seen the breakers soon enough to avoid them: besides, the wind blowing very fresh, the sea ran so high all round us, that we could not soon enough have distinguished the waves that broke on the reefs from the rest. Beyond these reefs, and near two leagues distant from them, we saw an island, which bore, when we made it, south 28° west, and to which I gave the name of Citizen Beaupré, engineer-geographer to our expedition. This island lies in the latitude of 20° 14′ south, longitude 163° 47′ east. It is very low, and about 1500 toises long. We afterwards discovered some rocks bearing south 21° east; and a little while after some others towards the south.

It is to be remarked, that the currents set us to the north about twenty-four minutes a day, when we were near Tierra del Espiritu Santo, and passing between that archipelago and new Caledonia. Undoubtedly this is owing to the position of the land, which, while it changes the direction of the currents determined by the general winds, increases their strength.

About one o'clock in the afternoon we got sight of the high mountains of New Caledonia to the south-west; and at half-after four we were within a thousand toises of the reefs bordering that island. The foot of the mountains on this side are washed by the sea, and they are likewise more steep here than on the western shore, which we coasted along the year before.

We saw a fine cascade, the water of which, after having disappeared several times in deep gullies, came tumbling into the sea; and we admired the picturesque effect of the torrents, which we perceived toward the south-west, their waters white with foam producing an agreeable contrast to the dusky verdure of these high lands.

During the night we continued plying to windward, endeavouring to maintain our station against the currents, that we might be in a situation to come to an anchor the next day.

19th. As soon as day-light appeared we approached within 800 toises of the reefs, along which we ran, in order to find the opening through which we were to reach the anchoring place; but it blew very hard from the south-south-east, and we had already fallen to leeward, when we distinguished the opening in the reefs. Though we were pretty near the shore, we did not perceive Observatory Island, which left us for some time doubtful whether we were opposite the place where Captain Cook anchored in 1774; and accordingly we put about, to get more to the the north-east. At noon we found by our observations, that we must be near Observatory Island, and it was not long before we got sight of it, though it is extremely low; when we immediately bore away for the anchoring place. In the opening between the reefs we had from eleven fathom water to thirteen and a half, but when we got within them we had only from seven fathoms to eight and a half.

A double canoe immediately came sailing out to us. She had on board eleven natives, whose manœuvres gave us no very high idea of their skill in navigation. They spoke to us, and showed us some pieces of white stuff, which they waved in the air, still keeping more than a hundred toises from the ship. A short time after they returned on shore.

The Esperance, being a little to windward of us, grounded on a shoal, which we in consequence took care to avoid, and presently after let go our anchor, in order to lend her assistance. General Dentrecasteaux immediately sent our long-boat to her, and at eight o'clock in the evening we had the agreeable news that she was again afloat, and had received no damage.

20th. At sun-rise the next morning we saw four canoes under sail, coming towards our ships. When they got very near us, they seemed to be under some fears: but one of the savages, having yielded to our invitations, and come on board, was followed by almost all the rest. We were surprised, to find them set more value on our stuffs than on our nails, or even hatchets, which they called togui; a name much resembling that given them at the Friendly Islands, though they do not speak the same tongue, as may be seen by the vocabularies of the languages of these people, at the end of the present work. We could not doubt, however, but they were acquainted with iron, which they designated to us by the denomination of pitiou; but the very hard stones which they use, renders it of less importance to them, than to many other inhabitants of the South Sea Islands.

We showed them some cocoas and yams, and requested them to bring us some: but, far from going to fetch any for us, they wanted to buy ours, offering us in exchange their spears and clubs, and giving us to understand that they were very hungry, putting their hands to their bellies, which were extremely flat. They expressed some fear on seeing the pigs which we had on board, which led us to suppose that they had no such animal; though Captain Cook had left two, a boar and sow, with one of their chiefs. As soon as they saw our poultry, however, they imitated

Double Canoe of New Caledonia. the crowing of the cock tolerably well, so as to leave us no doubt that they had fowls on their island.

None of the women in the canoes consented to come on board our vessel; and when we were desirous of making them a present of any thing, the men took it to carry to them.

These savages came in double canoes of the shape represented in Plate XLV. Fig. 1. Their mast was fixed at an equal distance from the two canoes, and toward the fore part of the platform, by which they were joined together. They are not so skilfully constructed as those of the Friendly Islands, to which they are much inferior in point of sailing. One of them, running against our ship with too much force, received so much damage, that the canoe on one side soon filled. The savages in her immediately got upon the other, and let themselves go with the current, which drifted them toward the shore. The other canoes left us presently after, and sailed after her, in order to give her assistance.

21st. Early in the morning we manned the capstan, in order to warp our ship nearer to Observatory Island; for which purpose we had carried out several hawsers tied end to end; but they gave way several times, and obliged us to let go the anchor again.

We were surrounded by canoes, the natives in which came on board our ship, and sold us several articles, such as are delineated in Plates XXXVII and XXXVIII. Some of them had a few cocoa-nuts and sugar-canes, which they would not part with by any means, though we offered a great price for them.

These savages were all naked, except that they wrapped their privities in pieces of coarse stuff, made of bark, or in large leaves of trees. Their hair is woolly; and their skin is nearly of as deep a black as that of the inhabitants of Diemen's Cape, whom they very much resemble in the general cast of their countenance. Several of them had their heads bound round with a little net, the meshes of which were large. We observed with surprise, a great many, who, desirous, no doubt, of having the appearance of long hair, had fastened to their own locks two or three tresses, made with the leaves of some plants of the grass kind, and covered with the hair of the vampire bat, which hung down to the middle of their backs.

Most of these islanders, armed with spears and clubs, carried at their waist a little bag full of stones, cut into an oval shape, which they throw with slings. (See Plates XXXV and XXXVIII. Fig. 16, 17, and 18.) The lower lobe of their ears, perforated with a very large hole, hung down

Effects of the Savages of New Caledonia.

Huts of the Savages of New Caledonia.

Woman of New Caledonia. to their shoulders. Into these holes some had introduced leaves of trees, others a piece of wood, to stretch them bigger. Several had this lobe jagged; perhaps from having been torn, either in battle, or in running through the woods.

Behind the ears of one of these savages we observed tubercles of the shape of a veal sweetbread, and half as big as a man's fist. He appeared well pleased at seeing us examine this ornament, the growth of which he had effected by means of a caustic, by which the parts, no doubt, must have been greatly irritated for a considerable time.

The women had no other garment than a kind of fringe, made of the filaments of the bark of trees, which served them as a girdle, passing several times round the waist (See Plate XXXVI).

The canoes kept themselves close by our ship, by means of different ropes, which we had thrown out to them. Each of them, however, had a large stone, to serve as an anchor, fastened to a long rope, but they did not make use of these on the present occasion.

22d. The next day we got up our anchor at six o clock in the morning, and made several stretches to get nearer to Observatory Island, which the natives call by the name of Pudyoua. At half after ten, when we brought up, this island was not above 500 toises distant to the east 3° 15′ south. We saw the land of New Caledonia from east 19° 30′ south, to west 12° north, from the nearest shore of which we were only 50 toises. The inhabitants now had no occasion for their canoes to come to us; most of them swam to the ship, with the articles which they wished to sell.

I ought not here to omit a malicious trick, which had nearly caused the loss of the young bread-fruit trees, that I had brought from the Friendly Islands. I had watered them in the evening; but, seeing some drops of water early in the morning trickle from the box in which they were planted, I had no doubt, but some one had watered them long after me. Of this I was fully convinced, the moment I tasted the water, that filtered through the mould; for it was salt. The inquiries I made to discover the person who had been guilty of this trick, were in vain.

About one in the afternoon we went ashore, and were soon surrounded by a great number of the natives, who just came out of the middle of the wood, into which we had entered several times, though still keeping near the shore. We presently found a few scattered huts, three or four hundred paces distant from each other, and overshadowed by a few cocoa trees. Soon after we came to four, which formed a little hamlet, in one of the gloomiest parts of the forest. They were all nearly of the shape of beehives, a toise and a half in height, and as much in breadth. (See Plate XXXVIII, Fig. 28, 29, 30).

Figure 28 represents one of these huts, surrounded by a palisade a yard and a half high, made with the limbs of the cocoa tree, arranged pretty close to each other, and three feet and half from the borders of the hut. A little walk was formed in the same manner before the door.

We afterwards saw several huts which were not surrounded by palisades (See Fig. 29). The door, which was about a yard high, and half a yard wide, was sometimes closed by means of a piece of a limb of the cocoa-tree, the folioles of which were interlaced. Several of these doors had two posts, made of planks, at the upper extremity of each of which a man's head was rudely carved. The lower part of these huts was erected perpendicularly to the height of a yard, where they tapered off in a pretty regular cone, terminated by the upper end of a post that was fixed in the centre of the floor.

Figure 30 represents the inside of these huts. The frame consists of poles, bearing against the upper end of the post, which may be seen rising from the middle of the floor, and which is near three inches in diameter at the bottom. A few pieces of wood bent to an arch, render these little habitations sufficiently strong. They are covered with straw to the thickness of two or three inches. The floor, on which the natives are perfectly sheltered from the weather, is spread with mats. But the moschettoes are so troublesome, that they are obliged to light fires to drive them away when they go to sleep; and as there is no vent for the smoke, except at the door, they must be extremely incommoded by it.

In general there is a board within the hut on one side, fastened with cords in a horizontal position, about a yard from the ground. This shelf, however, can support nothing of much weight, for the cords are very slight.

Near some of their dwellings we saw little hillocks of earth, twelve or fourteen inches high, with a very open treillis in the middle, of the height of two or three yards. The savages called these nbouet, and informed us that they were graves; inclining the head on one side, while they supported it with the hand, and closing the eyes, to express the repose enjoyed by the remains of those who were there deposited.

On returning toward the place where we landed, we found more than seven hundred natives, who had run thither from all parts. They asked us for stuffs and iron in exchange for their effects, and some of them soon convinced us that they were very audacious thieves. Among their different tricks I shall relate one which these knaves played me. One of them offered to sell me a little bag, which held stones cut into an oval shape, and which was fastened to his waist. He untied it, and held it out as if ready to deliver it to me with one hand, while he received the price agreed upon with the other; but at the very instant another savage, who hast posted himself behind me, gave a great scream, which made me turn my head round, and immediately the rogue his comrade ran away with his bag and my things, endeavouring to conceal himself in the crowd. We were unwilling to punish him, though most of us were armed with firelocks. It was to be feared, however, that this act of forbearance would be considered as a mark of weakness by the natives, and render them still more insolent. What happened soon after seemed to confirm this: several of them were so bold as to throw stones at an officer, who was not above two hundred paces from us. We would not yet treat them with severity; for we were so much prejudiced in their favour, from the account given of them by Forster, that more facts were necessary to destroy the good opinion we entertained of the gentleness of their dispositions: but we had soon incontestable proofs of their ferociousness. One of them having in his hand a bone fresh roasted, and devouring the remainder of the flesh still adhering to it, came up to Citizen Piron, and invited him to share his repast. He, supposing the savage was offering him a piece of some quadruped, accepted the bone, on which nothing but the tendinous parts were left; and, having shown it to me, I perceived that it belonged to the pelvis of a child of fourteen or fifteen years of age. The natives around us pointed out on a child the situation of this bone; confessed, without hesitation, that the flesh of it had furnished some one of their countrymen with a meal; and even gave us to understand, that they considered it as a dainty.

This discovery made us very uneasy for those of our people, who were still in the woods: shortly after, however, we had the pleasure to find ourselves all assembled together in the same spot, and no longer feared that some of us would fall victims to the barbarity of these islanders.

When we got on board our ship, being surprised at seeing none of the savages there, we were informed that there had been a great many, but that they had been driven away because they had stolen several things. Most of them had made off in their canoes; and the rest had jumped into the sea and swam ashore: two, however, were returned on board, not being able to swim fast enough to join the others, whether owing to some bodily infirmity, or to their having leaped into the sea too long after the departure of their boats to be able to take refuge in them. As the sun was already set, and they were cold, they went to warm themselves at the fire in our cook-room.

The most part of those who belonged to our expedition, and who had remained on board, would not give credit to our recital of the barbarous taste of those islanders, not being able to persuade themselves that people, of whom Captains Cook and Forster had given so favourable an account, could degrade themselves by such a horrible practice; but it was not very difficult to convince the most incredulous. I had brought with me a bone which had already been picked, and which our Surgeon-Major said was the bone of a child. I presented it to the two natives whom we had on board. One of those cannibals immediately seized it with avidity, and tore with his teeth the sinews and ligaments which yet remained. I gave it next to his companion, who found something more to pick from it.

The different signs which our people made, in order to obtain an avowal of the practice of eating human flesh, being aukwardly made, occasioned a very great mistake. An excessive consternation was instantly visible in all their features; doubtless because they thought that we also were men-eaters, and, imagining that their last hour was come, they began to weep. We did not succeed in convincing them entirely of their mistake, by all the signs we could make of our abhorrence of so terrible a practice. One of them made a precipitate retreat through a port-hole, and held fast by one of the ropes of the mizen mast shrouds, ready to leap into the sea; the other jumped into the water at once, and swam to the most distant of the boats astern of our vessel; they were not long, however, before they recovered from their fear, and rejoined our company.

The small stream, where Captain Cook had taken in water when he touched at this place, was dry when we visited it: we found, however, a small watering place to the south-west of our vessel, about three hundred paces distant from the sea: the water was very good, but it was rather difficult to be come at, and the reservoir which furnished it scarcely supplied enough to fill once in a day casks sufficient to load the long-boat of each ship, so that it was necessary to wait till next day till more was collected to replenish them.

We found very near this watering place the rusty bottom of an iron candlestick, which probably had lain there ever since 1774, when Captain Cook anchored in this road.

23d. The next morning we went on shore at the nearest landing place, where we found a number of savages who were already taking some refreshment. They invited us to join them in eating some meat just broiled, which we distinguished to be human flesh. The skin which yet remained, preserved its form and even its colour on several parts. They shewed us they had just cut that piece from the middle of the arm, and they gave us to understand, by very expressive signs, that after having pierced with their darts the person of whose limbs we saw the remnants in their hands, they had dispatched him with their clubs. They no doubt wished to make us sensible that they only eat their enemies, and indeed it was not possible that we should have found so many inhabitants in this country, if they had had any other inducement but that of hunger to make them devour each other. We went to the south-south-west, and soon crossed a country which lies rather low, where we saw some plantations of yams and potatoes; we then came to the foot of some mountains, where we found ten of the inhabitants who joined our company. They soon began to climb up trees of the species called hisbiscus tiliaceus, the youngest sprouts of which they pulled off and immediately chewed, in order to suck the juice contained in the bark. Others gathered the fruit of the cordia sebestina, which they eat even to the kernel. We did not expect to see cannibals content themselves with so frugal a repast.

The heat was excessive, and we had not yet found any water. We followed a hollow track, in which we remarked the traces of a torrent of water in the wet season. The verdure of the underwood, which we perceived a little farther off on its borders, gave us hopes of finding a spring to quench our thirst; in fact we were no sooner arrived than we saw a very limpid stream issuing from an enormous rock of freestone, and afterwards filling a large cavity hollowed out in a block of the same sort of stone. Here we halted, and the natives, who accompanied us, sat down by us. We gave them biscuits, which they devoured with avidity, though they were very much worm-eaten, but they would not even taste our cheese, and we had nothing eatable besides to offer them.

They preferred the water of the reservoir to wine or brandy, and drank it in a manner which afforded us no small entertainment, inclining the head at about two feet distance above the surface of the water, they threw it up against their faces with their hands, opening their mouths very wide, and catching as much as they could; thus they soon quenched their thirst. It may easily be conceived, that even the most expert at this method of drinking must wet the greatest part of their bodies. As they disturbed our water, we begged them to go lower down to drink, which request they immediately complied with.

Some of them approached the most robust amongst us, and, at different intervals, pressed with their fingers the most muscular parts of their arms and legs, pronouncing rapareck with an air of admiration, and even of longing, which rather alarmed us, but upon the whole they gave us no cause for dissatisfaction.

I observed in these places a number of plants belonging to the same genera with many of those I had collected in New Holland, although the two countries are at very great distance from each other.

We saw with surprize, about a third part of the ascent up the mountain, small walls raised one above another, to prevent the rolling down of the ground which the natives cultivated. I have found the same practice extremely general amongst the inhabitants of the mountains of Asia Minor.

It is not a common practice amongst the savages of New Caledonia to make an incision in the prepuce; nevertheless, out of six of them, whom we persuaded to satisfy our curiosity in that respect, we found one who had it slit in a longitudinal direction on the upper side.

When we had reached the middle of the mountain, the natives who followed would have persuaded us not to go any farther, and informed us that the inhabitants on the other side of this ridge would eat us; we, however, persisted in ascending to the top, for we were sufficiently armed to be under no apprehension of danger from these cannibals. Those who accompanied us were, without doubt, at war with the others, for they would not follow us any farther.

The mountains which we ascended rise in the form of an amphitheatre, and are a continuation of the great chain which runs the whole length of the island. Their perpendicular height is about 2,500 feet above the level of the sea. We observed them rise gradually to the east-south-east, till they terminated in a very high mountain about three miles from our moorings.

The chief component parts of those mountains are quartz, mica, and steatite, of a softer or harder quality, schorl of a green colour, granite, iron ore, &c.

On our descent from these mountains, we stopped at the bottom in the midst of several families of savages assembled in the neighbourhood of their huts, to whom we signified a desire to quench our thirst with the water of the cocoa nuts; but as this fruit is rather scarce in that part of the island, they consulted together for a considerable time before they agreed to sell us any. At last one of their number went to pull a few from the top of one of the highest trees, in order to bring them to us. We were extremely surprised at the rapidity with which he ascended, holding the body of the tree with his hands, he ran along the whole length of it, almost with as much ease and celerity as if he had been walking on an horizontal plain. I never before had occasion to admire such agility amongst any of the other islanders whom we had visited.

The sea water frequently washed the foot of the tree from which our cocoa nuts were taken, so that the liquor with which they were filled was somewhat sour, but we drank it, being extremely thirsty. The children of these savages waited till we had emptied the water of the cocoa nuts, when they begged them of us, finding means to get something more from them. They tore with their teeth the fibrous covering of these young fruits, of which the nuts were scarcely formed, and then eat the tender part enclosed in it, which was much too bitter for our palates.

When we arrived on board, we learned that two of the islanders had that morning carried off from an officer of our vessel (Bonvouloir) a uniform cap and a sabre, while he was occupied on shore making some astronomical observations, although the sailors, who had landed with him, had traced upon the sand a large circle round the place of observation, which they had forbidden the savages to enter; but two thieves having concerted their enterprise, advanced with precipitation behind the officer who had just sat down, and placed his sabre underneath him. One of them seized his cap, and the instant he rose up to pursue him, the other ran away with his sabre. This bold manœuvre was certainly not their first attempt.

Night approached, all our boats were already alongside, yet two officers (Dewelle and Willaumez) were still on shore, with two of the ship's crew, but they soon arrived on the beach, followed by a great number of the inhabitants. The General's boat was instantly dispatched to bring them on board. They told us that the savages, who had crowded around them, to the number of above three hundred, upon observing that all our boats had quitted the shore, had behaved in the most audacious manner. One of them having wrested his sword from Dewelle, the latter attempted to pursue the thief, but the others immediately raised their clubs in his defence. All of our people were robbed with the greatest effrontery, but when our boat arrived, two chiefs, who probably had prevented the savages from proceeding to greater extremities, begged leave to embark in it. They carried two small parcels of sugar-cane and cocoa-nuts to the General, who made them in return a present of an axe, and several pieces of stuff. Those chiefs, whom they called Theabouma in their language, wore on their head bonnets of a cylindrical form, adorned with feathers, shells, &c. (See Plate XXXVII, Fig. 1st and 2d.) but as they were open at top, they were no covering from the rain.

It was not long before a double canoe, dispatched from the shore, came to convey the chiefs back again. It was night before they departed, and the savages on shore had lighted a fire on a sand-bank to warm themselves. We went ashore on the 25th with those of the crew who were appointed to recruit our stock of wood, which they cut at a place 500 yards distant from where we had watered.

We did not stray far from our wood-cutters, for we were but few in number, and the designs of the natives appeared to us very suspicious. About nine in the morning they took possession of our shallop which was anchored near the coast, and only guarded by one man. They were already dragging it towards the strand, in order to carry off the effects that were in it with the greater ease, when another boat's crew came to its relief; but the thieves did not give up their enterprise till they were on the point of being fired upon.

Lasseny having gone on shore to make some astronomical observations, was obliged to re-embark almost immediately, being unable to keep off a number of savages who seemed inclined to attempt the seizure of the instruments, although he was armed and accompanied by two assistants, besides several of the boat's crew.

The master gunner of the Esperance, while hunting in the forest, perceived about noon, in a large open space not far from the wood-cutters, above two hundred natives, who were practising themselves in throwing their darts, and different exercises. He retired unperceived, and hastened to relate to us what he had just witnessed. One of the officers of our vessel immediately went with four fusileers to observe the motions of the savages; who, on perceiving them, advanced, and obliged them to make a precipitate retreat towards the wood-cutters. The savages soon repaired thither likewise; and we were not long before we discovered the design they had formed of seizing our axes, which had been laid in a heap in the midst of our workmen, who were assembled to take some refreshment. The commanding officer instantly gave orders for those tools to be carried into the long boat; but the sailor who attempted it was assailed by the islanders, who were on the point of carrying them off, when several musquet shots were fired. One of the most audacious, who fell on that occasion, had still strength enough to crawl as far as the wood. The others retired immediately, and saluted us with a shower of stones from their slings. The stones, which they carried in small bags suspended from their belts, were cut into an oval form; but they did not wound any one dangerously, on account of the great distance; besides, most of them were stopped by the branches of the trees, behind which the natives had taken refuge. This is not always the case when they fight among themselves; for being then probably less afraid to advance, they frequently have their eyes beat out in these battles, as several of the inhabitants, who had lost one of them, informed us. When they discharge the stones from their slings they only make half a turn with them above their heads, which is done with as much expedition as if thrown with the hand. These stones, cut from a steatite of considerable hardness, are very smooth, for which reason the savages take the precaution to wet them with their spittle, to prevent their sliding from the two small cords of which the bottoms of their slings are formed.

The different movements of these savages having been perceived from on board the Recherche, the General ordered two cannon-shot to be fired on them, which made them immediately disperse across the wood; but soon after one of their chiefs advanced towards us alone and unarmed, holding in his hand a piece of white stuff, made of the bark of a tree, which the Commanding Officer received as a token that the good understanding between us and the savages should not be interrupted. Soon after four other natives came and sat down in the midst of us with as much confidence as their chief, behind whom they placed themselves; but he seemed much displeased with several others who came to rest themselves under the shade of the neighbouring trees, whom he several times called robbers (kaya).

We re-embarked at four o'clock, P.M. and were already steering towards our ships, when we saw a troop of savages running along the strand towards us, loaded with a variety of fruits, which they had brought as a present for us. They leaped into the water several times to bring them to us, but we were driven in a westerly direction by a strong current, and could not stop to receive those marks of reconciliation.

I went on shore next day very near the watering place at the same time that the General arrived there. The guard was stronger than the day before, in order the better to keep the islanders in awe. It was feared after what had passed the preceding day, they might attempt to poison the water with which we were going to fill our casks, and it was thought necessary, according to the opinion of our Chief Surgeon, to try the experiment on a goose; but it was attended with no bad effects. Indeed, several of our sailors would not wait for the result of that proof, but, being very thirsty, had already drank of the water even before the commencement of the experiment.

The inhabitants having approached our place of landing, lines were drawn on the sand, the limits of which they were forbidden to pass, and we had the satisfaction to observe that they submitted peaceably to those orders. We gave to most of them pieces of biscuit, which they begged by extending one hand, whilst with the other they pointed to their bellies, which were naturally very flat, but the muscles of which they contracted as much as possible, to make them look still more empty. I saw, nevertheless, one man whose stomach was already well lined, but who, in our presence, eat a piece of steatite, which was very soft, of a greenish colour, and twice as large as a man's fist. We afterwards saw a number of others eat of the same earth, which serves to allay the sensation of hunger by filling the stomach, and thereby supporting the viscera of the diaphragm; although that substance affords no nutritive aliment, it is nevertheless very useful to these people, who are often exposed to long privations from food, because they neglect the cultivation of the soil, which is of itself very barren.

It is probable that the natives of New Caledonia have made choice of this earth on account of its being very liable to crumble; it is extremely easy of digestion, and one would never have suspected that cannibals would have recourse to such an expedient when pressed by hunger.

Three women having joined the other savages who surrounded us, gave us no very favourable idea of their music. They sung a trio, keeping time very exactly, but the roughness and discordant tones of their voices excited in us very disagreeable sensations, which the savages, however, seemed to listen to with much pleasure.

Lahaie, the gardener, and myself, ventured into the middle of the wood, followed by only two of the ship's company; we went from choice into those places where we thought we had least chance of meeting with the natives, who took care to conceal themselves behind bushes when they perceived us: at other times they hid themselves behind large trees, changing their position as we moved; but one old man, finding us approaching on both sides of the tree, behind which he was, so that he could not conceal himself, came up to us as if abandoning himself to our discretion, but he soon appeared satisfied he was safe when we gave him a few pieces of biscuit.

The gardener had already scattered in the wood different sorts of seeds which he had brought from Europe; but as some still remained, he gave them to the savage, requesting him to sow them.

We soon discovered a number of huts standing at some distance from each other, and were surprised at not finding any inhabitants in them. They were constructed in the same manner as that described in the beginning of this chapter: further on we perceived a heap of ashes; probably one of the habitations had been recently consumed by the fire which the savages kindle to drive away the musquitoes.

Two tombs which were not far distant had not sustained any damage. I saw two human bones, each suspended by a cord to a long pole stuck in the ground; the one was a tibia, the other a thigh bone.

I observed, on the hills which I crossed to return to our landing place, the tree called commersonia echinata, which is very common in the Moluccas. Amongst the different sorts of shrubs which I gathered was a jessamine remarkable for the plainness of its leaves and its flowers, which have no smell, and are of the colour of marigolds.

Several fires lighted near the summit of the neighbouring mountain convinced us that it served as a retreat for the natives.

On arriving at our landing place we found a great number of savages who had assembled there since our departure. They informed us that several of the inhabitants had been wounded in the affair of the preceding evening, and that one had already expired of his wounds. They did not manifest any hostile dispositions towards us; but a boat belonging to the Esperance being at a considerable distance from thence towards the east, had been attacked by another party of savages, who thought they were in force sufficient to make themselves matters of it, but fortunately they failed in the attempt.

We were told on arriving on board that not a single canoe had approached our vessels, which we thought was rather to be attributed to a smart gale which had blown the whole day, than to any fear of our resentment for the hostile disposition manifested by them the preceding evening.

We had formed a design, together with several persons belonging to the two vessels, to go and visit the other side of the mountains, bearing south of our moorings; for this purpose we assembled on the shore to the number of twenty-eight, early in the morning of the 20th. We had all agreed to come armed, that we might be able to render mutual assistance, in case the savages should venture to make an attack upon us.

We marched for a long while in paths that were well beaten, accompanied by some of the inhabitants, and many of us, in imitation of them, chewed the young sprouts of the hibiscus tiliaceus, and threw them away almost immediately; but to our great surprise the savages eagerly picked, them up, and chewed them over again without the least hesitation.

When we had reached the middle of the mountain we found very large blocks of mica, wherein we perceived granites which had lost their transparency, and most of them larger than a man's thumb. We found others farther on in the rocks of freestone, which were very small, but retained their lustre.

A smoke which we observed to issue at intervals from a grove at a small distance to the S.S.W. induced us to direct our course that way. We there found two men and a child occupied in broiling, on a fire of charcoal, the roots of a sort of bean, which is known to botanists by the name of dolichos tuberosus, and which the islanders call yalé. They had been but recently dug up, for the stalks were still hanging to them, and were covered with flowers and fruits. They partook of the barrenness of the soil which produced them, the fibres were very stringy, and they were not not more than three-quarters of an inch in thickness, and about ten or eleven inches in length.

We met very near the same spot with a small family, which appeared to be alarmed at our approach. We immediately made each of them a few presents, in hopes of encouraging them, which had the desired effect upon the husband and two children: but one of our people having offered a pair of scissars to the mother; and wishing to shew her the use of them, by cutting off a few of her hairs, the poor woman began instantly to cry; no doubt giving herself up for lost: but her fears subsided as soon as she was put in possession of the instrument.

The inhabitants of these mountains appeared to us to live in the greatest wretchedness. They were all extremely meagre. They sleep in the open air without being tormented by the musquitoes; for these insects are driven from the high grounds by the E.S.E. winds, which blow here almost incessantly. The same winds are so prejudicial to vegetation, that trees which below grow to a great height, here wear the appearance of shrubs. Melaleuca latifolia, for example, is scarcely fourteen inches high, whereas on the hills it attains the height of twenty-seven or thirty feet. But still there are vegetables peculiar to the summits of those mountains, which appear to agree perfectly well with the current of air to which they are thus exposed. I shall give a description of one of the most remarkable. It forms a new genus, which I distinguish by the name of dracophyllum.

The calix is composed of six small oval leaves, pointed towards the end.

The corolla is in one piece, and divided slightly on the border into six equal parts. It is surrounded with six small scales at the lower end.

The stamina, to the number of six, are attached to the corolla by small fine threads, nearly of the same length with the antheræ.

The ovarium is at the top, of a roundish form, and surmounted by a style, of which the stigma is of a simple form.

The capsule is composed of six cells, each containing a number of seeds, most of which are unproductive.

I ought to observe, that one of the parts of fructification is often wanting.

I have given this plant the name of dracophyllum verticillatum, its flowers being disposed in rings.

These leaves are rough, and slightly dentated, or notched, on the edges. They leave their impression on the stalk as they separate from it, as is the case with all sorts of dracæna, with which that plant has a great analogy, even in the texture of the wood it produces. It is therefore of the division of minocotyledon, although it has a calyx and a corolla, and naturally takes the next place to the species of asparagus.

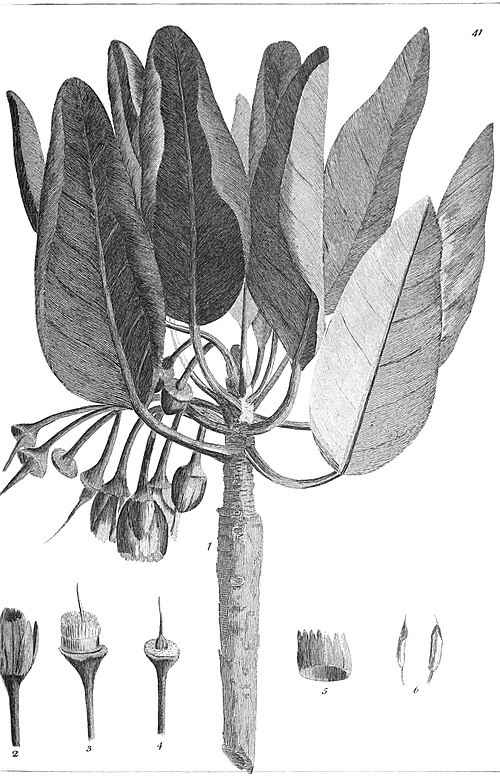

Explanation of the Figures, Plate XL.

Fig. 1. The plant.

Fig. 2. Blossom.

Fig. 3. The corolla magnified and cut obliquely, to shew the stamina.

Fig. 4. The capsule.

Dracophyllum Verticillatum. In examining from the summit of these mountains a great extent of breakers which defend the approach to this island, we observed another passage, at a small distance to the west of that by which our vessels had reached their present moorings. Towards the south we had a prospect of a delightful valley, surrounded with large plantations of cocoa trees, from amongst which we saw columns of smoke arising, from the fires made by the savages. Vast fields, which appeared to us to be cultivated, even in the lowest parts, indicated a great population. The valley was traversed by a canal filled with water, which we mistook for a river, the different branches of which came from the foot of the eastern mountains; but we afterwards found that this canal was filled with stagnated sea-water. We perceived towards the south-west the shoal, along which we had sailed the year before; and we distinguished the same inlet in it which the violence of the wind had prevented us from sounding. It appeared to us a place of safety for such vessels as wished to anchor out of the reach of breakers.

We were only followed by three natives, who no doubt had seen us sail along the western coast of their island last year; for before they had quitted us, they spoke of two vessels they had seen in that direction.

We proceeded for some time along the tops of the mountains towards the south-west, then we descended into a hollow, where we found two men and a child, who showed no concern with respect to us, and did not quit the rock upon which they were seated. When we were close by them, they shewed us a basket (see Plate XXXVIII. Fig. 24), filled with roots, resembling those of a kind of sun-flower called helianthus tuberosus. They called them paoua, saying that they were good to eat, and they wanted to sell us a small quantity.

Perceiving, at about thirty yards distance, a thick smoke issuing from the midst of large broken rocks, which offered a good shelter from the wind, we directed our course towards it, and found a young savage busy roasting some roots, amongst which we distinguished those of the dolichos tuberosus. He did not appear surprized at our visit, and smiled at us from the bottom of his cavern, which was filled with a very black smoke, whereby he however did not appear to be at all incommoded.

Near this place the side of the mountain, laid open by the torrents which descend in the rainy season, discovered to us clusters of beautiful pieces of green schorl in a soft steatite, and below that small fragments of a very transparent rock chrystal.

In returning to our vessel we came through a small village, the inhabitants of which left their huts unarmed. They allowed us to examine the inside of them, and one of them, without any hesitation, sold us some human bones which were hanging up over one of their tombs.

We soon after arrived on the sea coast, where we found a party of the natives who followed us, begging something to eat, but as all our provisions were consumed, I gave them some green steatite, which I had brought from the summit of one of the mountains; some of them eat as much as two pounds weight of it.

Whilst we were embarking in order to return on board, one of the crew fired his piece in the air to unload it, which struck such a panick in most of the islanders who were on the shore, that they instantly ran off to conceal themselves in the woods; but some of them, confident of our good intentions towards them, shewed no symptoms of fear, but called back the fugitive, who soon rejoined them.

On the 27th I was obliged to remain all day on board, in order to arrange and write descriptions of various articles which I had collected the day before.

We received a visit from several of the natives who swam to the vessel. They were at great pains to assure us that they were not in the number of those who had committed acts of hostility against us, and they told us they had eaten two of those robbers, or kaya, one of whom had received a ball in the thigh and another in the belly in the engagement with us, but we did not give entire credit to this story, supposing they had fabricated it to screen themselves from suspicion.

They brought with them an instrument which they called nbouet, a name which they likewise gave to their tombs; it was formed of a fine piece of flat serpentine stone, with sharp edges, and nearly of an oval form, perfectly well polished, and of the length of nearly seven inches. It was perforated with two holes, through each of which passed two very flexible rods, whereby it was fixed to a wooden handle, to which they were fastened with bands made of bat's-skin. This instrument was supported by a pedestal made of a cocoa-nut shell, which was likewise tied with strings of the same kind, some of which were longer (See Plate XXXVIII, Fig. 19). We could not till then discover the use of this instrument; these savages told us that it was to cut up the limbs of their enemies, which they divided amongst them after a battle. One of them shewed us the manner, by imitating it on one of the ship's company, who, at his desire, lay down on his back. The savage first represented a combat, in which he indicated by signs that the enemy fell under the strokes of his javelin and club, which he brandished with great violence. He then performed a sort of warlike dance, holding in his hand the instrument of murder; he then shewed us that they begin by opening the belly with the nbouet, throwing away the intestines, after having torn them out with an instrument (represented in Plate XXXVIII. Fig. 20), made of two human cubitus, well polished, and fixed to a very strong tape. He shewed us they next cut off the parts of generation, which fell to the share of the conqueror. The legs and arms are cut off at the joints, and distributed, as well as the other parts, amongst the combatants to carry home to their families. It is difficult to describe the ferocious avidity with which he represented to us the manner in which the flesh of the unfortunate victim is devoured by them, after being broiled on a fire of charcoal.

The same cannibal gave us likewise to understand that the flesh of the arms and legs is cut into pieces about three inches thick, and that the muscular parts are reckoned by these people a very delicious morsel. It was no longer difficult for us to conceive why they felt our legs and arms with their fingers in a longing manner, at which times they made a slight whistling noise, produced by shutting the teeth, and applying the end of the tongue to them, then opening their mouths, they gave several smacks with their lips.

We went on shore on the 28th, but not being in sufficient numbers, durst not venture to go far beyond our watering place. We no longer saw in the environs large parties of natives, as on the first days after anchoring here, which made us think that they had returned to their habitations, probably at a considerable distance from this place: indeed how could such a vast number of men have found the means of subsistence on a coast so extremely barren.

Next day (the 29th), we set off early, to the number of eighteen, all well armed, with the intention of ascending a very high mountain, situated to the south-south-east, and from thence descending, if the weather should prove favourable, into a delightful valley, which we had already perceived at a great distance behind the mountain.

We marched at first towards the east along the

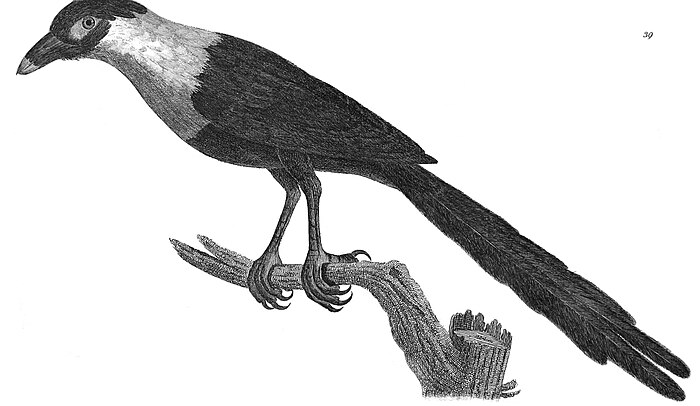

Magpie of New Caledonia. shore, and soon entered an extensive wood, when, amongst other birds which we killed, there was a species of pie, which I named the pie of New Caledonia. It is entirely black except the breast, shoulders and neck, which are white. The bill is rather jagged at the extremity of each mandible, and is of a light black from the root to within one-third of the point, the remainder is yellowish. The feathers of the tail are arranged in rows two by two, the upper ones being much longer than the others (See Plate XXXIX, in which the bird is represented.)

We had already proceeded above a mile, when we arrived at a villege composed of a small number of huts, sufficiently distant from each other to prevent the flames from communicating in case of any unfortunate conflagration. Two of them had been recently consumed. We there saw women cooking victuals, composed of the bark of trees and a variety of roots, amongst which I discerned those of the hypoxis, of which I have already made mention. These different articles were put dry into a large earthen pot, supported over a fire by three large stones, which supplied the place of a trevet. We observed near the entrance to one of those huts a large heap of human bones, on which the recent effects of fire were very evident.

It was probably an inhabitant of this village who stole the sabre of Bonvouloir, as related above, for here we found the sheath and belt suspended over one of their tombs, as a kind of trophy.

Upon leaving this village, we followed a beaten path to the south-east, where we were not long before we saw some Caribbee cabbages (arum esculentum), planted near a rivulet, the stream of which the inhabitants of the island had turned off lower down to a plantation of arum macrorrhizon. Farther on we remarked some young banana trees planted at five or six yards distance from each other, as also some sugar canes.

Soon after this we were surrounded by at least forty of the natives, who came out from the adjacent huts, and from some straggling cottages scattered in an extensive plain covered with plants and shrubs, above which rose a small number of cocoa trees; but we were astonished to see only very few men amongst these savages, all of whom were either old or infirm, and most of them cripples. The remainder consisted of women and children, who testified much joy at receiving some presents of glass ware which we gave them. We presumed that the stout men were engaged at a distance in some expedition against their neighbours.

We were about one mile distant from the first village when we discovered another twice as large, situated on the borders of a small river, along which we went upon a rising ground in a southerly direction. Upwards of thirty natives came out to meet us, and followed us for some time. We soon perceived three others descend from the mountains, one of whom we knew, having received several visits from him on board the Recherche. Several amongst the natives pointed him out to us as a chief of great distinction, whom they called Aliki.

We sat down on the borders of the small river to take some refreshment, and to prevent the danger of any surprize from the savages, we invited them to sit down. Aliki immediately complied with our invitation, and his example was followed by the others. The water being a few paces below us, the savages filled our bottles as fast as we emptied them.

After breakfast we ascended towards the south, accompanied by Aliki and three other natives, who testified a strong desire to follow us. Some cocoa and banana trees, planted on the least rugged of the borders of the hollow formed by the waters of the small river, pointed out to us the residence of some of the natives. We found there a hut exactly like those which we had seen before. Aliki said the hut belonged to him. It was surrounded with several of a new species of fig tree, the fruit of which those people eat, after having exposed it to the fire for some time in earthen vessels, in order to extract its corrosive quality.

Clouds, brought on by a brisk gale from the south-east, covered the tops of the mountains about ten in the morning, and occasioned a heavy shower of rain, of which the savages took scarcely any notice. They did not even seek for any shelter, whilst we retired underneath the thickest trees. As soon as it ceased we continued our route, and they followed us with many marks of friendship. One of them, wishing to relieve a sailor who was loaded with a large tin-box, filled with a variety of objects of natural history, carried it for above four hours.

We soon after crossed over the small river, on the banks of which I observed the acanthus ilicifolius. We then ascended very rugged rocks for a considerable time, and were under great obligations to the savages, who exerted themselves in supporting us by the arms, to prevent our falling.

Each of them carried an axe of serpentine stone; and one of them wishing to show us how they made use of them to cut wood, hacked off a branch of the melaleuca latifolia, about four inches thick.

It was not till after a number of strokes, that he was able to make a slight notch in it, then he broke it by forcibly bending down the end of it; they all shewed the greatest surprize at seeing us cut down in a short time, with a military axe, some of the largest trees in the forest.

We had just reached the summit of one of the highest of those mountains, when one of our people made signs to the savages that he wished to have some water to drink. Immediately two of them offered to go and fetch some from a hollow that appeared to be above half a mile distant. They set off, and we soon lost sight of them. As they were a long time before they returned, we were afraid they had gone away with the bottles we had entrusted them with, but at last they returned, and appeared pleased that they had it in their power to offer us some very pure water to quench our thirst.

After this we descended towards the south-east and crossed a fine valley, where I made a copious collection of plants, among which were the acrostichum australe, and several new species of limodorum.

A very heavy rain obliged us to seek for shelter in the hollows of the rocks, where we remained for some time. We invited the savages who accompanied us to partake of our repast, but were much surprised to find those cannibals reject with disdain the salted pork which was offered them.

The badness of the weather having prevented our continuing all night on the mountains, we returned towards our vessels, going in a westerly direction, in order to follow the declivity into a large valley, parallel with that which we had just crossed. I there observed many new species of passiflora. The ginger, amomum zingiber, grew there abundantly, but the natives told us they made no use of it. As soon as we arrived on the shore, where we found our boats in waiting, to take us on board the ships, they quitted us, and went off to the eastward.

I employed the whole of the 30th in describing and assorting the numerous collection of articles of natural history, which I had made the day before.

May 1st. This day we went towards the south-east, and after having penetrated a considerable way into the woods, we arrived at a hut surrounded with palisades, behind which were a woman and two children, who appeared frightened on our approach, but they resumed their courage upon our presenting them with some pieces of cloth, and a few glass beads.

We next went towards two great fires that were kindled by the savages in one of the most gloomy parts of the forest. They dispersed as soon as they perceived us, leaving two baskets filled with the bark of trees.

Soon after we arrived on the borders of some marshes, where we killed several beautiful birds of the genus muscicapa: they had been attracted thither by the swarms of musquitoes, which served them for food. Further on we found two young girls who had just lighted a fire: they were dressing for their repast different sorts of roots, amongst which I recognized several belonging to plants which I had met with under the shade of the large trees in the forest. The girls left their provisions for some time, retiring as we approached them.

On our quitting the wood, we met with several savages who accompanied us to our landing place. They were much amused with seeing Citizen Riche's dog pursue some of the natives who were at a considerable distance, and whom he soon overtook, though they ran as fast as they could. As he did them no injury, those who were with us begged us to set him at some women who were then coming out of the wood, and were anticipating their fright, but we would not be persuaded to comply with their request.

We were witness, on arriving at the shore, to a fact which proves the great corruption of manners amongst these cannibals. There were two girls, the oldest of whom was not more than eighteen, who were shewing to our sailors that part which they are accustomed to conceal with the fringed girdle mentioned above, and which forms the whole of their clothing. A nail, or something of equal value, was fixed upon as the price of this favour; but they took care to make their curious customers pay beforehand.

Upon returning to the ship, I found a chief who had dined at the table with the officers. He had come in his canoe, accompanied by his wife, whom he would never allow to come on board, notwithstanding our repeated requests to that purpose.

On the 2d we went a shooting in the great woods, which we had not explored, to the south-east, where we killed a prodigious quantity of birds. We stopped in a small village, where we saw over two tombs pieces of wood rudely carved: the inhabitants told us that it was forbidden to approach them; but they consented very readily to sell us in exchange for some pieces of cloth a human scull that was suspended over another tomb, the coronal bone of which was fractured on the left side. They informed us, that the warrior it belonged to had been killed in battle by a club.

Next morning early, twenty of us set off with an intention to cross the mountains, and from thence to descend into the extensive valley, where, in one of our excursions, we had descried at a great distance a considerable number of cultivated fields. It was probable that we should there meet with a great number of inhabitants, but we were sufficiently well armed to be able to repel any attack which they might venture to make.

At first we followed the coast, advancing towards the west, and penetrating from time to time into the woods, we saw a number of inhabitants quit their huts, and leave behind them a net which they had spread out to dry. It appeared that that implement of fishing is very rare amongst these savages: its common size is about eight yards in length, and eighteen inches in breadth. They shewed us but very few of them during our whole stay in the Island, and no price could tempt any of them to part with one.

We perceived near this place a great quantity of broken shells of fish, which had served the Islanders for food. We found several of the species known by the name of benitier, of the length of twelve or thirteen inches. They still bore the marks of the fire which had served to dress the animal contained in them.

The women principally are employed in fishing for shell-fish. We saw some of them from time to time, opposite to where we lay at anchor, who advanced into the water up to their waists and gathered great quantities, which they discovered in the sand, by means of pointed sticks with which they groped for them.

We had already gone about three miles along the coast without finding any stream of water, when three young savages came to meet us, and persuaded us to follow them to their cottage, not far out of our road. We then found a spring, below which they had dug some trenches to conduct the water to some plants of the arum macrorrhizon, the roots of which they eat.

We were on the slope of a small hill, under the shade of some cocoa trees. One of the savages, whom I requested to procure us some of their fruit, climbed to the top of the tree with an extraordinary degree of agility.

We soon after continued our course to the westward. The air was serene, and the heat excessive, and we were attacked by a cloud of musquitoes, which tormented us very much, by stinging every part of the body, not even sparing our eyes and ears. Fortunately a breeze of wind springing up soon after, relieved us from their persecutions, by dispersing them.

Soon after this we arrived on the borders of a deep canal, which went in an inland direction to the foot of a very craggy mountain. This canal served as a harbour for the islanders, three of whom we saw enter it in a double canoe, which they immediately fastened with a rope tied to the foot of a tree on the same side we were. They then went at a slow pace towards the small hills on the south-east, pretending not to have perceived us. Their canoe was the only one in the harbour. We made use of it to cross to the other side, where we found a small cottage, the plantations contiguous to which had been recently laid waste. We full perceived some remains of Caribee cabbages, and of sugar canes. The tops of all the cocoa trees had been cut off, and perhaps inhabitants had fallen victims to the voracity of the barbarians who had thus destroyed them.

Till then we had never met with any of the tombs of the savages, except close by their huts, but we now found one at a great distance from any habitation whatever, on the side of the road which we pursued. It differed from the others, being built of stone from the base till about half way up.

We halted about noon, under the shade of several casuarina equesetifolia, and of several new species of cerbera, which grew on the banks of a rivulet, where we quenched our thirst, and in which we found some fragments of roche de corne, brought down by the water. We caught two sea-snakes (coluber laticandotus), which we broiled and eat, but found very tough and ill tasted.

We were about eleven miles distant from our vessels when fresh marks of devastation made us lament the lot of the wretched inhabitants, whom revenge often prompts to the commission of the most horrible excesses. They had destroyed the principal habitations, and cut off the tops of all the cocoa-trees about them, having only spared two small sheds which were covered with spongy bark of the melaleuca latifolia.

Presently after a forest of cocoa trees, whose tops we perceived at the distance of a mile and a half to the west, together with several columns of smoke which rose in different directions, were indications of a great population. We directed our course toward this place for some time, but the marshy ground which we must have crossed to reach it, caused us to abandon our design; besides, the day drew towards a close. We then went southward in search of a commodious situation to pass the night in, when we soon pitched on an eminence, the difficult access to which secured us from being surprised by the savages. We lighted a fire, for the cold was sharp and piercing on these high grounds, and we felt it the more sensibly, as during the day we had experienced in the plain a very great degree of heat.

I gave all the birds which I did not mean to preserve to those of the ship's crew who accompanied us, and amongst those which they broiled immediately for our supper were several of the corvus caledonicus, and some very large pigeons of a new species, which I had before met with on the first days after our arrival.

We all supped and then went to sleep, leaving two of our number to watch by turn, for it was to be feared that the light of our fire would bring some of the islanders to us. In a very short time we were apprised that the light of several torches, with which the savages were approaching our retreat in an easterly direction, was perceived towards the foot of the mountains. In an instant we were all on our legs to observe their motions, and prepared to give them such a reception as circumstances might render necessary in case of attack; but after traversing several small hills, they descended towards the coast, getting farther from us to the eastward. Perhaps these cannibals were upon some expedition against their enemies. As we did not appear to be the object they were in quest of, we immediately lay down again to sleep, trusting to the vigilance of our centinels.

4th. At day-break we ascended towards the south-east, and were not long before we reached the summit of the mountain, from whence we perceived, toward the west-south-west, on the sea coast, the great opening of the canal which traverses the plain we proposed to visit.

We soon descended into a valley, nearly about the middle of which stood a delightful grove, to appearance planted by the hand of man, but it was only the goodness of the soil, moistened by the water from the neighbouring mountains, that rendered the bushes so strong and luxuriant. I then collected a great number of plants, amongst which I found a new kind of fern of the myriotheca species, the tallest of which rose to the height of twelve feet, although the stem was not more than three inches and three quarters in circumference.

On leaving the grove we perceived two natives about three hundred yards below us, going towards the plain, of which we now discovered the full extent. They looked at us without stopping, notwithstanding the signs of invitation we made them to come to us. One of them carried on his shoulder, at the end of a stick, a basket, in all probability filled with roots.

We had only a few more small hills to cross before we reached the plain, when several of our companions, apprehensive that we should be in want of victuals if we went much farther, or perhaps that we should meet with numerous parties of savages, left us and returned to the ships early in the day. Our number was now reduced to fifteen, upon their departure; nevertheless we continued our journey. We soon found by the side of a path which seemed much frequented by the savages, several cabbage-palms, and having refreshed ourselves with the tender leaves from the tops of those trees, we descended into a hollow, where several fine aleurites added to our repast a plentiful dessert of fruit, the kernels of which we found of a very agreeable flavour.

The quartz and mica which were spread over a large space, formed in that place a foliated rock of a very brilliant appearance, composed of a thin strata.

We at length gained the plain, where the melancholy sight of a habitation entirely destroyed, and cocoa trees cut up by the roots, furnished us with fresh proofs of the barbarity of the natives.

Farther on we saw plantations of yams, potatoes, &c. We proceeded for some time towards the south, and were surprised at not seeing any of the savages, when I perceived an old man employed in pulling up the roots of the dolichos tuberosus, which he gave to a child to clean. He did not seem in the least intimidated on observing us approach him, but every feature of the child was expressive of the most violent apprehension. The old man had lost one eye, which he told us had been knocked out by a stone, and we thought we recognised him to be one of those inhabitants who had come several times to visit us on board of our vessels.

This man accompanied us along the path in a south-easterly direction across the plain, but had much difficulty in keeping up with us, for he had been wounded in one leg, where we perceived two great scars opposite to each other, as if it had been pierced through and through with a dart.

On both sides of the road we saw straggling huts at great distances from each other, surrounded with cocoa trees. Only a few savages appeared at a distance in the middle of the vast plain. On our right lay a thick forest of cocoa trees extending to the foot of the mountains, on the edge of which we perceived a great number of huts.

We had gone a little more than a mile with the savage, when he persuaded us to stop in the neighbourhood of a habitation, probably his own, for he invited us to gather the fruit of the cocoa trees which surrounded it ourselves, excusing himself from climbing the trees on account of his wounds. I gave him some pieces of cloth of different colours, and some nails, which he seemed to value highly.

Soon after another savage came to us, and both followed us till we came to the banks of a branch of the great canal which crossed the plain; it was filled with stagnant water, equally salt with that of the sea.

We perceived at a distance some women and children, when our two savages left us, after having pointed out the path which conducted us to the mountains.

At the same instant some other natives set fire to the dry grass at a great distance before us on the side of the path which we were following, and immediately disappeared in the woods.

After proceeding about half an hour, I arrived on a very agreeable eminence, where the natives had built themselves sheds about six feet in height, in order to enjoy the fresh air. They were of a semicircular form, and open at bottom all round to the height of about one foot, to admit a free circulation of air. We found no savages in either of two neighbouring huts, which were built near a bog, surrounded with the hibiscus tiliaceus; but contiguous to them we saw a large cultivated field, covered with yams, potatoes, and a sort of hypoxis, the roots of which those people eat, and which grows spontaneously in their forests.

It was already one hour after dark, when we at last arrived at the summit of the mountains; from whence, looking in a north-west direction, we perceived the lights of our vessels. At six or eight hundred paces below were several fires, lighted by the natives. The cold compelled us likewise to kindle a very large one, round which we sat down to refresh ourselves, after which we went to sleep, leaving two sentinels to guard two passages by which the islanders might come to surprize us, but none of them attempted to disturb our repose. Only at day-break the sentinel who was to the north-east espied three of them approaching very slowly, but they returned back on hearing him cry out to warn us of their coming.

5th. All our provisions being consumed, we felt sensibly the necessity of returning on board. I could not, however, resist the desire I had to spend a few hours in visiting a charming grove of trees, situated on the other side of the mountain, at a small distance from the place where we had passed the night. I there observed a great quantity of plants, which I had not yet found in any of the excursions I had made in this island. They belonged chiefly to the class of the silver tree and the trumpet flower.

I will here give a description of one of the finest shrubs which grows on these heights. It forms a genus which I call antholoma, and which ought to be placed amongst the species of the plaqueminiers.

The calyx, composed of from two to four leaves of an oval form, often falls off when the flower blows.

The corolla is of one piece in the form of a cup, and irregularly indented on the edges.

The stamina are numerous (about an hundred), and attached to a fleshy receptacle.

The ovarium is of a pyramidal form, quadrangular, slightly sunk into the receptacle, and surmounted by a style terminated by a pointed stigma.

The fruit has four cells filled with a great number of seeds; it was not yet ripe, but I think it becomes a capsule.

I have distinguished a shrub by the name of antholoma montana, many plants of which I observed fifteen feet in height. Its leaves are alternate, very strong, and, as well as the flowers, are only to be found at the extremity of the branches.

Explanation of the Figures in Plate XLI.

Fig. 1. Branch of the antholoma montana.

Fig. 2. Flower.

Fig. 3. Receptacle, stamina, and ovarium.

Fig. 4. Corolla.

Fig. 6. Stamina magnified.

One of the geographers of our company having left us about this time for the distance of rather more than half a mile, in order to ascertain the position of the shoals which he discovered from a high peak, received a visit from a savage, who approached him in a threatening manner; he was armed with a dart and a club, and we were afraid he intended to attack him, but he contented himself with examining the instruments which he was using, without giving him the smallest cause of complaint.

We arrived at our vessels about noon. I observed along the coast a double canoe with two sails. It was constructed like those of the islanders of New Caledonia, but the men who were in it spoke the language of the natives of the Friendly Islands. They were eight in number, being seven men and

Antholoma Montana.

Woman of the Island of Beaupré.Man of the Island of Beaupré. one woman, all very muscularly built (See Plate XXXIV.) They told us that the island from whence they came was a day's sail to the east of our moorings, and that the name of it was Aouvea; it was doubtless the island of Beaupré which they meant.

These islanders, who were quite naked, had the end of the prepuce tied to the lower part of the belly by a cord of the outer covering of the cocoa nut, which went twice round them. They know the use of iron, and appeared much more intelligent than the natives of New Caledonia.

I was much surprized to see one of the planks of their canoes covered with a coat of varnish; and it appeared to have belonged to some European vessel, which I was convinced of when I found that the powder of lead formed a great part in the composition of the varnish. Without doubt the plank had belonged to a vessel of some civilized nation wrecked on this coast. I requested the savages to inform us of what they knew concerning the plank; they set sail soon after to the west, promising to return next day to bring us information; but they did not keep their word; and we never had an opportunity of seeing them again.

When we returned, we were informed that the same day that we had left the ship on our excursion, the savages had attempted to seize the hatchets of our wood-cutters, whom they had attacked with stones, but two musket shots had been sufficient to disperse them.

I employed the whole of the 6th to describe and arrange the numerous collection of articles of natural history which I had brought with me from the mountains.

Next day the intelligence of the death of Captain Huon, which we learnt at day-break, spread a general sorrow amongst all those concerned in the expedition. This skilful naval officer had fallen a sacrifice to a hectic fever about one o'clock in the morning, after an illness of several months. He met death with the greatest coolness, and was interred, according to his particular desire, near the centre of the island of Pudyona, favoured by the veil of night. He had requested that no kind of monument might be erected for him, apprehensive that it might lead to a discovery of his burial place by the inhabitants of New Caledonia.