Wood Carvings in English Churches II/Chapter 7

PART II

———

CHAPTER VII

BISHOPS' THRONES

In the next chapter we deal with movable chairs and thrones, descendants more or less of the "sella curulis" and the "sella gestatoria." More important still are the fixed thrones of Early Christian days. These were not of wood or ivory, but of masonry, usually marble. In shape they were just high-backed chairs of marble. Now countless numbers of such marble chairs or stalls were in use in the theatres, thermæ and amphitheatres of Pagan Rome; the thermæ of Caracalla alone possessed 600 such marble stalls. Doubtless many a bishop's throne, like those at St John Lateran, St Clement and Cosmedin, Rome, was actually taken from one of the Roman thermæ. Similar bishops' chairs, cut out of the solid rock, occur in the catacombs of Rome.

The position of the fixed marble throne of an Early Christian bishop was high up in the centre of the back wall of the apse of the church.

In Dalmatia and Istria several thrones retain their original position. At Parenzo there remains the semicircle of marble seats for the clergy with the episcopal throne in the centre; a work of the first half of the sixth century. At Aquileia, in the centre of the east end, is the Patriarch's throne of veined white marble, inlaid with serpentine; it is made up of portions of an older throne of genuine Byzantine work. At Grado the marble throne at the east end of the church seems to have been made up in the ninth century; it is surmounted by a stone tester. At Zara in the same position is another marble chair, raised on five steps. At Trau the bench of the clergy remains, but the bishop's throne has been destroyed. At Ossero also is a marble throne made up of fragments of older work.[1] In the apse of the twelfth century church of S. Stefano, Bologna, is a bishop's throne ten steps above the choir. Another remains in situ in Vaison cathedral, Provence. Another episcopal chair of marble is now placed on the north side of the sanctuary of Avignon cathedral; on it are carved the emblems of the Evangelists (104).

Exeter

Exeter

In the Victoria and Albert Museum is a throne, painted and gilded, dated 1779, from a church in Cyprus. In Norwich cathedral in the centre of the apse wall of the presbytery there are the fragments of the original stone seat built for the use of the bishop, and on the pavement and adjoining piers there are traces of the steps by which his throne was reached. When Blomfield wrote his History of Norfolk, 1739-1775, the steps of the throne had not been disturbed; "the ancient bishop's throne ascended by three steps," and when built, before a rood screen was erected, the bishop had an uninterrupted view down the whole church to the west end of the nave.[2]

Avignon

In Canterbury cathedral is a stone chair, which as at Norwich was originally at the back of the High altar; it was removed from that position by Archbishop Howley c. 1840, but has recently been replaced; it consists of three blocks of Purbeck marble (105). The chronicler Eadmer, writing of the Pre-Conquest cathedral burnt down in 1067, says that "the pontifical chair in it was constructed with handsome workmanship and of large stones and cement." The description would apply very well to the present chair: but the monk Gervase states that in Lanfranc's cathedral, finished in 1077, "the patriarchal seat, on which the archbishops were wont to sit during the solemnities of the Mass, until the consecration of the Sacrament, was of a single stone." It would seem therefore that the Anglo-Saxon chair perished in the fire of 1067, and that its successor experienced the same fate in 1174. The probability is therefore that the present chair was made between the fire of 1174 and the consecration of 1184. A decisive argument against a Pre-Conquest date is the fact that the throne is made of Purbeck marble—for this material seems not to have come into use till after the middle of the twelfth century in the Norman house at Christchurch on the Avon, in St Cross', Winchester, and in William of Sens' work at Canterbury.

Canterbury

The position of the pontifical throne at Canterbury has varied at different periods. Eadmer states that the cathedral burnt down in 1067 was orientated to the east, where was the presbytery containing the High altar. But at the west end of the church was the altar of Our Lady, and behind this altar was the throne adjoining the west wall. This unusual position is only explicable by the assumption that the first cathedral at Canterbury was orientated to the west, and that the site occupied in 1067 by the altar of Our Lady was originally that of the High altar. The western position so postulated for the High altar and the throne was originally that of most of the Early Christian basilicas at Rome, in particular the ancient basilica of St Peter. At a later period the orientation was often reversed, e.g., in St Paul extra muros, Rome; what happened in this latter church seems also to have happened in Anglo-Saxon times at Canterbury. A similar change has occurred in the French cathedral of Nevers; where, however, though in Gothic days a presbytery and High altar were constructed at the east end of the church, the early Romanesque presbytery, crypt, and two bays of the nave have been allowed to remain to this day.

What looks like a survival of the marble chair of the bishop is to be seen in the frithstols of Hexham and Beverley (106). These also are of masonry, and are so similar in design to the ancient marble thrones that one is tempted to speculate that the original usage of sanctuary was for the offender to fly to and occupy the actual throne of the bishop or archbishop.

As has been said, in the Early Christian churches both the altar and the seats of the bishop and his clergy were usually at the west end of the church to the west of the High altar, so that the clergy faced towards the east, while the congregation faced towards the west. But early examples occur of churches with the modern orientation. When this was the case, the congregation faced east; and where the ancient position of the throne and benches was retained, the clergy were left in an anomalous position facing west. This led, first to the clergy, then the bishop, migrating elsewhere. The higher clergy took up their position in the return stalls of the choir, facing east; the lower clergy occupied stalls north and south of the choir. As for the bishop, he could not seat himself as before, facing the altar, for his throne would have blocked the entrance into the presbytery. He therefore set up his throne on the south side of the choir, at the eastern end of the southern range of stalls. And this is where we find him in Gothic days. There is one chief exception. In cathedrals served by monks, the bishop was the titular abbot of the house, though the superintendence of the monastery had necessarily to be left mainly in the hands of the prior; and so to this day in some churches the bishop has no throne, but occupies the ancient abbot's stall—at Ely the stall of the Benedictine abbot, at Carlisle the stall of the Augustinian abbot.

Durham

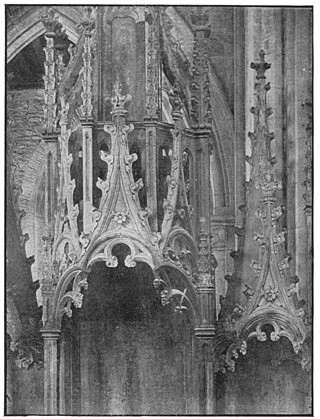

The change of position from the back of the High altar to the front of it was a complete break with tradition. Equally complete was the break in design. In the design of the Gothic throne there is no reminiscence whatever of the marble chairs of the Early Christian basilicas and the Pagan Thermæ. The Gothic thrones are but glorified versions of such stalls and spirelet-tabernacles as those of Lincoln; they are spacious stalls, sometimes, as at St David's, big enough to hold a bishop and two chaplains, and crowned with a spire of open woodwork. The earliest and grandest is that of Exeter cathedral; the Fabric Rolls shew that in 1312 during the episcopate of Bishop Stapledon there was paid "for timber for the bishop's seat £6. 12s. 8½d." The oak was kept four years before it was used. Then £4 was paid to Robert de Galmeton "for making the bishop's seat by contract." There was also a charge of 30s. for painting, and there must have been one for carving the statues in the canopy. The whole cost would be about £13; say £200 in our money; a sum surprisingly small for work of such magnitude and delicate detail. The throne was evidently intended to have a chair placed under it, and probably seats for the bishop's chaplains to the right and left. It is 57 feet high; at present its niches look somewhat unsubstantial and meagre; but that is because all the niches were tenanted with statues, and all have disappeared. The carved foliage is of exceptional excellence, and the corners of the pinnacles are occupied with small heads of oxen, sheep, dogs, pigs, monkeys and other animals (102).

St David's

St David's

Not much later is the throne in Hereford cathedral. That at Wells is fifteenth century work, and by a pretty fancy of the "restorers" its tracery is filled with modern plate glass, and the door is a solid swinging stone! That at St David's is nearly 30 feet high. Of the throne erected by Bishop Gower c. 1342 there remains in situ only the low partition surrounding it; the present throne was probably put up by Bishop Morgan between 1496 and 1504 (109).[3]

The throne at Durham is of masonry, and in two parts of different dates. The lower portion contains an altar tomb surmounted by a recumbent effigy of the bishop in richly worked robes beneath a rich lierne vault. No doubt Bishop Hatfield as usual put this up during his lifetime; he was bishop from 1345 to 1381. This lower part is an exquisite example of the design in vogue before the advent of the Black Death of 1349-50. On the tomb is the pulpit, which bears unmistakable marks of the change of style which became general after 1350. The drawing shews the throne as it was in 1843 (107).