CHAPTER XVIII.

IN THE AZTEC STRONGHOLD.

[A. D. 1519.] The city of Mexico, built on an island in Lake Tezcoco, was connected with the mainland by four causeways of stone. That by which Cortez approached, six miles in length, commenced at Mexicalcingo, and, crossing the lake to the island, was prolonged on the north to Tepeyacac, where is now the shrine of Guadalupe; another ran nearly west, and the fourth, which supported an aqueduct, terminated at Chapultepec. All centred in the great square of the city, from which branched other streets and canals, or streets one-half water and the other half solid earth. All these causeways were intersected by broad ditches to allow passage to the water of the lake, crossed by wooden bridges that could be easily raised, and thus cut off the retreat of an enemy brave enough to advance over them.

The grand causeway was eight yards wide, and ran straight to Mexico. In good order, the Spaniards marched over it between the assembled thousands of Indians. At about a mile from the city this causeway was joined by another from the town of Coyoacan, and at their juncture was a small, though strong, fortress, with walls ten feet high, battlements, two entrances, and a drawbridge. This point was called Xoloc, and was occupied by Cortez in the following year as his military headquarters, whence he directed the siege of the city. The army halted here, and waited, until more than a thousand Mexican nobles had passed by and saluted the general. As this salute consisted of a low bow, touching the earth with the hand and then kissing it, the halt was a very long one. An hour or two later the army moved on, and just as the city limits were reached they were informed that the great Montezuma was approaching. They halted and Cortez dismounted from his horse. The monarch appeared, borne in a litter upon the shoulders of four nobles, while others carried golden rods in front to indicate his coming. The litter was covered with plates of gold, its canopy ornamented with green feathers, gold, and pendants of precious stones. Supported upon the arms of two of his principal lords, Montezuma, having alighted from the litter, advanced to meet Cortez. He wore upon his head a golden crown, rich mantles, worked with gold and jewels, hung from his shoulders, and upon his feet were golden sandals, tied with strings of leather ornamented with gems.

As they met, Cortez threw upon his neck a string of glass beads, and would have embraced him had not the lords in attendance interposed. Montezuma made a short speech of welcome, and in return for the glass beads gave the audacious stranger two necklaces of mother-of-pearl, hung with beautiful crayfish of gold. Having then given orders to his brother. Prince Cuitlahuatzin, to conduct Cortez and his army to the palace provided for them, he returned to the city with the King of Tezcoco. The entire populace had been drawn out to observe this extraordinary spectacle. As Montezuma passed, attended by his nobles, they crowded close to the walls, not daring even to lift up their eyes.

On the western side of the great square, which contained the holy pyramid and the temples and altars to their various gods, stood the palace of Axayacatl, father of Montezuma. Into this immense building, which contained ample room for them all, not less than seven thousand in

MEETING OF CORTEZ AND MONTEZUMA.

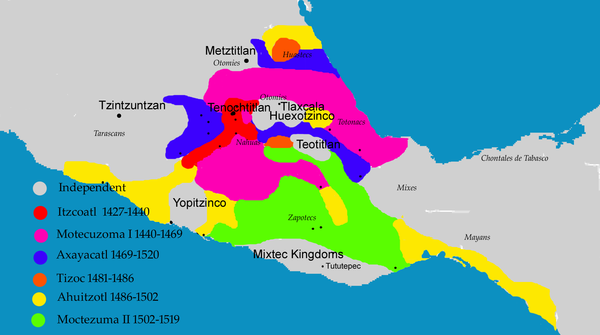

Aztec Expansion.

number, the Spanish army was conducted. Montezuma and his nobles stood waiting for them at the gate, and, when they had arrived, took Cortez graciously by the hand and showed him his apartment, at the same time placing a valuable collar of gold about his neck. The walls were hung with tapestry of cotton with golden fringe, mats of rushes and palm leaves covered the floors, low seats of wood were provided as chairs, and everything in and about the palace was neat and clean. Then giving orders to his officers to prepare provisions and refreshments for his weary guests, Montezuma said to Cortez, "You are now in your own house," and withdrew, leaving the Spaniards amazed at the magnificence of their surroundings and the munificence of the emperor.

After the grim and battered warriors had filed in, with their Indian allies and attendants, Cortez planted cannon to defend the gate, distributed guards about the parapets, and then, having placed himself in a posture of defence, fired a salute from the cannon, in order to terrify the Mexicans and to express their triumph in having at last reached the goal of their desires.

This memorable day, the eighth of November, 1519, seven months after their arrival on the Mexican coast, was terminated by a banquet, at which the nobles served them, and distributed to officers and soldiers abundance of such as the land produced.

The following day, Cortez, attended by five of his captains, paid a visit to Montezuma in his own palace, which was reached by crossing the great square. They were graciously received by the lords-in-waiting, and, after having been required to cover their garments with coarse wrappers and to put off their shoes, they were admitted into the royal presence. Montezuma put many questions to them about their country of Spain and its government, and finally Cortez drew the conversation upon religion, which he explained to the king, was the real object of his embassy. He drew a touching picture of the concern of the King of Spain—a monarch who sanctioned the burning of heretics in his own dominions—for the souls of the inhabitants of Mexico. He told him—what was utterly false—that this great monarch had such deep sympathy for them, and was so desirous of leading them away from the worship of idols, that would only destroy their souls, that he had despatched him on his mission. Montezuma made a reply, in substance the same as that given by the Tlascallans to a similar request that they should abandon their idols: that their gods were good enough for them, that they gave them sun, and rain, and victories; he desired Cortez to say no more on the subject. This interview ended with another present from Montezuma to the Spaniards: to the general he gave a large quantity of golden ornaments, to each of the captains three loads of mantles, and to each soldier two loads of these valuable articles, richly wrought. He was so generous and affable that he won the heart of every soldier, and if he entertained any designs against them he well concealed his feelings beneath an appearance of content, even of gayety.

"He was at this time about forty years of age, of good height, and well-proportioned, with a complexion much fairer than that of the Indians in general, wearing short black hair, and a very thin beard. His countenance was pleasing, and gravity and good humor blended together when he spoke." His clothing was often changed, as he was cleanly in his habits, and bathed frequently; and a garment having been once worn, was not put on again for four days after. A thousand people comprised his household." His cooks had upwards of thirty different ways of dressing meats, and had earthen vessels so contrived as to keep them always hot. For the table of Montezuma himself, above three hundred dishes were prepared, and for his guards above a thousand; the ordinary meats were pheasants, geese, quails, venison, peccaries, pigeons, hares and rabbits, with many other animals and birds peculiar to the country. Torches of aromatic wood gave light in winter; the table was covered with snowy cloths and napkins, and four beautiful women presented him with water for his hands in vessels which they called Xicales—or calabashes. A screen was placed before him when he ate, to shield him from the gaze of the vulgar, and four ancient noblemen stood near the throne at this time, to whom Montezuma occasionally presented a plate of food, which they ate with every token of humility. Fruit of every kind was placed before him, and from time to time he drank a little foaming chocolate, which was presented him in golden cups. Sometimes he had singers and dancers to amuse him, as well as deformed and hump-backed dwarfs, acrobats, and jesters. After he had dined, four female attendants brought him water with which to wash his hands, and then they presented him with three little canes, highly ornamented, containing liquid amber mixed with tobacco; and when he had sufficiently viewed and heard the singers, dancers, and buffoons, he took a little of the smoke of one of these canes, and then laid himself down to sleep; and thus his principal meal was concluded."

About the great square in the centre of the city were grouped all the principal buildings; within it were the temples, the largest of which was the holy pyramid—the teocalli—(already described in Chap. III.) and various others. There was one like an immense serpent, which Bernal Diaz, one of the conquerors, said he could never pass without comparing it with the infernal regions, for at the door stood frightful idols; by it was a place for sacrifice, and within it boilers and pots full of water to dress the flesh of the victims, which was eaten by the priests. The idols were like serpents and devils, and before them were tables and knives for sacrifice, the place being covered with the blood which was spilled on those occasions."

Near this temple was another, full of bones, and skulls and skeletons, piled in heaps and laid in rows. The dwellings of the priests, the colleges and nunneries, were within the vast enclosure also. The great wall which surrounded it had four gates, above which were places for the collection of the royal arms. In the Place of Skulls, these ghastly emblems were symmetrically arranged, and when one dropped from its place, owing to decay, it was replaced by a fresh one. Some of the conquerors declared "that they counted the skulls preserved in this horrible place, and that there were one hundred and thirty-six thousand!

The favorite palace of Montezuma was built of stone, whitened with lime, and had twenty doors opening into the public square. It contained more than a hundred chambers, three great courts adorned with fountains and gardens, and apartments finished in jasper and marble. One of these halls was so large that it would hold, according to credible testimony, three thousand persons. Upon the roof of some of the buildings, some of the Spanish officers declared, there was ample room for a tournament! These roofs were flat, and sometimes with battlements; the houses were of stone, one and two stories in height, sometimes roofed with stone and sometimes with thatch; but all with immense beams of cedar and cypress. Two great houses about the central square were devoted to the animals of the kingdom, and contained every variety of bird and beast it was possible to obtain, even snakes and alligators. The birds alone demanded three hundred men for their daily care, and they had physicians also, who carefully noted their diseases and prescribed for them. Strong wooden cages contained pumas, jaguars, wolves and wild-cats, to whom, it was said, were thrown the bodies of the sacrificed victims, after the limbs had been reserved for the table of the priests. Outside of the city there were woods, in which the emperor hunted, and gardens and groves in which he delighted to ramble, supplied with canals of running water, fountains and springs, like those of Chapultepec, which exist to this day.

About this vast square, also, were the palaces of the nobles and the lords of distant provinces, who were obliged to reside here a portion of their time; the royal arsenal, full of every kind of aboriginal weapons, shields, and helmets; in fact, all the public buildings and residences of Mexico's greatest men were here. There were other squares and market-places, temples and towers, scattered all over the city, so that it was a most magnificent city to behold, and one to convey to a stranger an idea of vast wealth and power. No wonder that the Indians of the mountains were impressed with a sense of its grandeur, and thought the King Montezuma to be the mightiest potentate on the face of the earth!

One day, Cortez ascended to the top of the great pyramid, and there Montezuma met him and pointed out to him the notable places in the valley and the chief buildings in his city. Here the Spaniard saw that grim old idol, Huitzilopochtli, with human hearts smoking before him on some coals, and other idols to which the Aztecs had been sacrificing for a hundred years and more. Cortez attempted to reason with Montezuma upon the folly and wickedness of worshipping such hideous images: "I wonder," said he, "that a monarch so wise as you are can adore as gods those abominable figures of the devil." This he said half in jest, but Montezuma,—to whom they seemed as really gods as the image of the Virgin to Cortez,—was shocked and grieved, and replied sadly: "If I had known that you would have spoken disrespectfully of my gods, I should not have yielded to your request to visit the platform of the temple. Go now to your quarters, go in peace, while I remain to appease the anger of our gods, which you have provoked by your blasphemy."

The king was more liberal in his views than Cortez, for he allowed him to build an adoratory for his own god, and even gave him workmen and material for the purpose. Soon after, he gave him and his soldiers more presents; great pieces of gold for Cortez, ten loads of fine mantles for him and his captains, and to every soldier two loads of mantles and two collars of gold.

In a short time, the Spaniards had visited the greater portion of the city—the people paying no particular attention to them after their first curiosity had been gratified, so well-bred were they—they had visited the great marketplace where all the productions and commodities of the kingdom were gathered for sale, the courts of justice, and the temples.

It was in looking for a niche in which to place their holy emblem of the cross, that the Spaniards found the depository of Montezuma's treasure! They broke through a wall in one of the apartments and there saw "riches without end;" a vast quantity of works of gold, gems, gorgeous feathers and fabrics, silver and jewels. The secret soon leaked out, and all the soldiers had a glimpse of the royal treasure, which had been accumulated during the lifetime of Axayacatl, father of Montezuma. It was left untouched for a more convenient time, and the wall closed up. "I was then a young man," wrote the conqueror, Diaz, "and I thought that if all the treasures of the earth had been brought into one place they could not have amounted to so much." A week had elapsed, the Spaniards had tired of sightseeing, their allies longed for active work in the field, their cupidity was aroused by the sight of so much treasure: they longed to get it into their possession; in short, they were getting restless and were desirous of an opportunity for departure. But how could they do this without exciting the fears of the multitude by whom they were surrounded, and causing them to rush upon and massacre them in the streets? The past days and nights had been to Cortez full of anxious thought. He had placed himself in a predicament from which he saw no escape except by artful strategy; he had played a deep game, he could win only by bold moves. At last he thought he saw an opening out of the difficulty; if he could get the emperor into his power he might then be able either to retreat with honor, or to stay in comparative safety. But how could they do this? He had given them no pretext for seizing his person, he had not shown by word or deed that he bore them aught but the best of feeling; he had treated them like princes—they, the offscourings of Spain; had enriched them, petted and caressed them. Yet they could not believe but that he meditated evil; they judged his nature by their own; they knew what they would do had affairs been reversed, and had they been the rulers of his kingdom and he and his nobles their guests—they would have burnt him as an idolater within twenty-four hours of his coming!

Now, history has not shown that Montezuma intended to deal by them treacherously, even though the events of that time were recorded by men belonging to the nation of the conquerors themselves; yet, forgetting all his generous treatment of them, they resolved to seize him, hold him prisoner, and, if necessary, kill him! A pretext was found in an outbreak, in one of Montezuma's provinces on the coast, against the Spaniards left in garrison at Vera Cruz.

Quetzalpopoca, lord of a province contiguous to the Totonacs, had undertaken to bring the latter people under subjection. The Spanish garrison had gone to the assistance of the Totonacs, but, though they defeated Quetzalpopoca, had lost six or seven soldiers, and among them their governor, Juan de Escalante. One of the soldiers, who had an enormous beard and fierce visage, was sent as a prisoner to Montezuma, but, having died on the way, his head was cut off and presented to the emperor. Montezuma was so terrified at the ferocious aspect of this hideous trophy—the first European face he had ever looked on—that he refused to have it offered in any of his temples, and retired to a place of seclusion, greatly troubled by the event. This occurred while the Spanish army was in Cholula, and Cortez had heard of it at the time, but had kept it to himself. Now, he considered it a proper time to mention it to his soldiers, and a sufficient cause for taxing Montezuma with treachery. Having consulted with his captains, it was determined on to seize the king the very next day; and in the morning the interpreters, Aguilar and Marina, were despatched to notify the king that Cortez would visit him at his palace. He and five of his captains entered the audience-hall where they were received with much affection, and presented with some gold. Cortez soon revealed the nature of the business he came on, charging Montezuma with not only instigating the attack on the Spaniards at Vera Cruz, but also the meditated massacre at Cholula. The astonished monarch declared his innocence, and taking from his wrist a ring bearing the signet of Huitzilopochth—the royal seal, upon presentation of which no man dared disobey the, bearer of it—and giving it to an officer of his court, he commanded him to bring Quetzalpopoca and those responsible for the attack upon the Spaniards into his presence. With this, Cortez declared himself much pleased, but added that he and his men would not be satisfied unless the king would consent to return with them to their quarters—in the palace of the late king, Axayacatl—and there take up his abode with them till the return of the guilty parties.

The king was thunderstruck at the audacity of such a proposal, and as soon as he could recover his senses made reply: "When was there ever an instance of a king tamely suffering himself to be led into prison? And although I were willing to debase myself in so vile a manner, would not all my vassals immediately arm themselves to set me free? I am not a man who can hide myself or fly to the mountains; without subjecting myself to such infamy, I am here now ready to satisfy your complaints."

Cortez was firm, however, in persisting that he should go with them, adding that, if his subjects should attack them, they could defend themselves—forgetting, perhaps, that the very reason why he wanted Montezuma in their power was to prevent the dreaded attack.

Much argument ensued, the king giving decidedly the best reasons, when one of the soldiers, a brutal captain, spoke up in a rough voice, advising Cortez to waste no more words, but, unless he yielded, to run him through with a sword. Learning the meaning of these words, and fearing he would be murdered before his guards could come to his assistance, Montezuma cowardly yielded to his fears, and said in a trembling voice: "I am willing to trust myself with you; let us go, let us go, since the gods intend it."

Ordering his litter he got into it, and in pomp and magnificence, though closely guarded by the Spanish troops, he went from the palace, looking his last upon the hall where he had so often sat in state, for he was never to enter it again! News of such an event as this could not fail of being rapidly spread amongst the people, and there would certainly have been an uprising and attempted rescue had not Montezuma commanded his nobles to threaten with death any one who should attempt it, and declared that the visit to the Spanish quarters was made of his own free will.

His domestics preceded him and hung an apartment with fine tapestry and transported furniture from the royal palace. They ministered to his wants as before, and he preserved the same state, giving audiences to his subjects in the same manner as when he was in supreme control. But he was now a monarch only in name, as the subsequent dealings of Cortez with him fully show.

The officers bearing the signet of the god returned in fifteen days with the culprits, Quetzalpopoca, his son, and fifteen others. They were richly dressed; putting off their shoes and covering their fine garments with coarser ones, they came into the presence of Montezuma. He received them coldly, reprimanded them for attacking the Spaniards, and then delivered them over to Cortez.

If there is anything that can reconcile us to the ignoble treatment of Montezuma by the Spanish chief, it is his baseness in delivering his vassals up to torture in order to shield himself from the consequences of his own policy and commands. There is no doubt that he commanded this lord to reduce the Totonacs to obedience—as he had a right to do, as rebellious subjects—but he had not the spirit to admit as much to the Spaniards.

Quetzalpopoca and his officers were handed over to the Spaniards, to be dealt with as traitors to the Spanish king, of whom they—the subjects of Montezuma—had never heard before in their lives! In the centre of the square a large collection was made of darts, arrows, bows, and shields, from the royal armory, which Cortez was anxious to get rid of, as they might be of use against him in the hands of the Indians, in case of outbreak. Upon a vast pile of these the brave Mexicans were placed and fire applied. The flames leaped up and enveloped them, and soon, after exhorting one another to face death courageously, perished Quetzalpoppca and his companions, the first martyrs by fire to Spanish cruelty in Mexico.

We look with horror upon such an act as this, even after the lapse of more than three centuries, but in Mexico it was not regarded with deep feeling; and even in "Christian" Spain, forty years later, the burning of a heretic was made an occasion of feasting and rejoicing! What would not the bloody Philip of Spain have given for such a lieutenant as Cortez? Reading—if he ever read—the list of his executions, he must have exclaimed with regret, " Ah! here was a man in advance of his time; would that I had such as he to purge my kingdom with fire and sword! "

As the smoke of this terrible sacrifice ascended and spread over the valley, it carried with it the mutterings of an outraged and a revengeful people; the subjects of Montezuma could be held in check but little longer; the nobles were gathering their forces, even the priests—blind devotees of Montezuma's god—were disgusted at the servility of their king. That cloud of smoke was charged with thunder; from it was to dart the lightning that was to destroy the Spanish forces!