CHAPTER V.

THE RIVAL POWERS OF ANAHUAC.

[A. D. 1350-1431] In 1350, the Mexicans elected their first king, Acamapichtli. This was done without the consent of the King of the Tepanecs, who resided at Azcapozalco, on the mainland, and to whom they paid tribute. The Tepanec king forthwith doubled their tribute, and also imposed several very hard conditions for their remaining in Mexico. He ordered them to bring to his capital several thousand willow and fir trees, and to plant them in the gardens of Azcapozalco, as well as one of their floating gardens, with all their vegetables growing on it. The next year he commanded them to bring him one of these chinampas, with a duck and a swan sitting on their eggs, and at such a time that they would hatch upon arrival at his court. Next year's command was that they should bring him one of these gardens with a live deer on it, knowing that they would have to go to the mountains, amongst tribes at war with them, to procure it.

They fulfilled all their obligations, owing to the help given them by their god, and patiently waited for the time when they should be freed from the exactions of the king; they are said to have endured them for fifty years. The founding of the city of Mexico, in 1325, was during the reign, probably, of the Chichimec king, Quinatzin, with whom we closed the account of that people in chapter the third. He was succeeded by King Techotl, who was lowed by Ixtlilxochitl, in the first years of the fifteenth century, probably in 1406.

[A. D. 1389.] Acamapichtli, Kng of the Mexicans, died in 1389, and the throne was given to the brave Huitzilihuitl

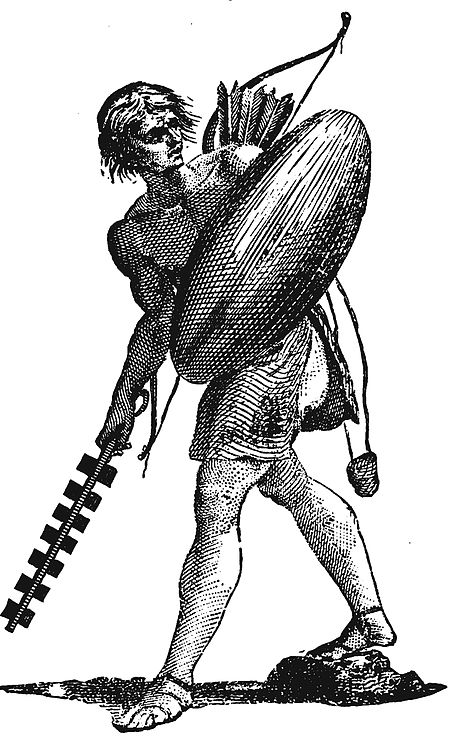

MEXICAN WARRIOR.

He was a young man and unmarried, and some of the nobles went to the King of the Tepanecs, their master, and humbly besought him to give them his daughter to be married to their king.

The following speech, put in their mouths by the historian, will illustrate their abasement and their cunning: "Behold, great lord, the poor Mexicans at your feet, humbly expecting from your goodness a favor which is greatly beyond their merit. Behold us hanging upon your lips, and waiting only your signals to obey. We beseech you, with the most profound respect, to take compassion upon our master and your servant, Huitzilihuitl, confined among the thick rushes of the lake. He is without a wife, and we without a queen. Vouchsafe, sir, to part with one of your jewels, or most precious feathers. Give us one of your daughters, who may come to reign over us in a country which belongs to you."

The king was not proof against this sort of flattery. He gave them his daughter, and she was married to King Huitzilihuitl, by the usual ceremony of tying the skirts of their robes together. Having strengthened himself by the possession of this "precious feather," the crafty king procured another wife, also the daughter of a neighboring lord. There is no knowing how many wives he did get, for he was very anxious to strengthen Mexican relations with their neighbors, and there was no law against his marrying as many as he pleased.

Techotl, the King of Tezcoco, was yet ruler over the valley, and in suppressing an extensive rebellion he called upon the kings of Mexico and Azcapozalco to aid him. As they returned covered with glory they acquired respect from the surrounding tribes. Under Huitzilihuitl, the Mexicans prospered as never before; they began to wear clothes of cotton, having had till this time only coarse garments made of the threads of the wild palm, and perhaps of the maguey.

[A. D. 1402.] The Tlatelolcos, the people forming the other division of Mexico, had also elected a king, and for many years there was a great rivalry between them and the Mexicans. But King Huitzilihuitl dug canals, erected fine buildings, multiplied the chinampas, and trained soldiers, using so much vigilance and energy that the Tlatelolcos were left behind in the march of improvement. Eventually, as the marshes between the two cities were filled up, they were only separated by a canal, and the rival factions were united into the more powerful government of Mexico.

In 1402 the Mexicans celebrated the closing of one of their cycles, or centuries, with greater magnificence than any since they had left their homes in Aztlan. Their prosperity was assured, their position unshaken.

Ixtlilxochitl, son of Techotl, succeeded his father upon the throne of Tezcoco. At his inauguration, all the princes or petty kings of his dominion were ordered to assemble at the capital to witness the ceremony and acknowledge him emperor. The King of Azcapozalco was ambitious to be at the head of affairs in Anahuac, and absented himself from the court at the time when he should have been present. He stirred up a rebellion that involved many of the lords of the valley, and finally Ixtlilxochitl marched upon him with the royal army. After three years of fighting, Tezozomoc, the King of Azcapozalco, sued for peace, and the Tezcocan army was withdrawn from his territories. But this was an artifice, and as soon as Ixtlilxochitl had disbanded his army, he found himself in great danger from his cunning foe, who pursued him even to the mountains, where he was finally murdered, or died in misery.

[A. D. 1410.] The year previous, Huitzilihuitl, King of Mexico, had died, and his brother, Chimalpopoca, was appointed king. It seems to have been established as a law at that time, that on the decease of a king one of his brothers should be appointed to the throne, or, if he had no brothers, one of his grandsons. The tyrant, Tezozomoc, was now ruler of Anahuac, having, at the death of Ixtlilxochitl, swept the valley with his armies. He gave Tezcoco to Chimalpopoca to be lord over, and another city, Huexotla, to Tlacatcotl, King of Tlatelolco, as rewards for their assistance.

Azcapozalco was proclaimed as the royal capital and the seat of power, with Tezozomoc as emperor. As mistress of the valley, Tezcoco had fallen from her high position; the Chichimec dynasty was no longer to control the Mexican world, though in a few years the ancient capital was to revive its glory by becoming the centre of art and culture. The legitimate heir to the crown, Nezahualcoyotl, son of Ixtlilxochitl, was now a fugitive, with a price set upon his head by Tezozomoc the usurper.

For nine years, the tyrant held the throne of Tezcoco, with his capital at Azcapozalco. He was now very old, and approaching his end; not having within him sufficient vitality to keep him warm he was kept wrapped in cotton, in a great willow basket like a cradle. His hatred of the Tezcocan prince continued to his last breath, and as he had not been able to put him to death, he charged this unpleasant duty upon his sons, his successors to the kingdom. He was greatly troubled by hideous dreams, in all of which figured Nezahualcoyotl, the young prince he had driven from his home. He dreamed that this foe was at one time changed into an eagle, and in this shape tore open his breast and ate his heart; at another, in the form of a lion, he licked his body and sucked his blood.

[A. D. 1422.] Tormented with fears for the future of his kingdom and for his own miserable life, Tezozomoc expired, in the year 1422. The kings of Mexico were in attendance as mourners at his funeral, as also was the Prince of Tezcoco, whom the sons of Tezozomoc wished to kill, but dared not from fear of the people.

Chimalpopoca, King of Mexico, lost his throne and his life at this time under peculiar circumstances. Tezozomoc had left the kingdom to his son Tajatzin, but another son, Maxtla, took possession of it. Tajatzin complained of this injustice to Chimalpopoca, and was advised by the Mexican king to kill his brother at an entertainment which he should prepare. This Maxtla heard of, and acted so promptly that he not only killed Tajatzin, but succeeded finally in making captive Chimalpopoca himself.

When the King of Mexico sent his annual tribute to Azcapozalco, consisting of fish, cray-fish and frogs, accompanied by a polite message to the king as lord of the valley, Maxtla showed his contempt for him by sending back by the embassadors a woman's gown, thereby implying that the Mexican king was a coward. After this insult, which Chimalpopoca was unable to avenge, Maxtla succeeded in getting a favorite wife of his enemy into his power, and after doing her all the injury he was capable of, he sent her back to her husband in tears and misery.

Chimalpopoca resolved, as he could not take revenge on the tyrant, to sacrifice himself as an offering to his god, Huitzilopochtli. This, in his opinion, and in the eyes of his people, would wipe out the insult, to him as a king, and to the nation he ruled over. Dressed in the garb of sacrifice, the unfortunate king was led to the temple, where the priests stood ready to plunge into his breast the knife of flint, and to tear out his troubled heart and offer it to their god. But the tyrant anticipated this event and despatched troops to the temple, who seized Chimalpopoca and hurried him to Azcapozalco, where they confined him in a strong wooden cage. Here he was visited by the fugitive Prince of Tezcoco, to whom he related his woes, and besought him to. remember his poor people, the Mexicans, if he should succeed in gaining again the ancient throne of Acolhua. Then, giving him a golden pendant from his upper lip, and his ear-rings, which had once been worn by his famous brother, Huitzilihuitl, he charged him to escape at once from the dominions of Maxtla.

[A. D. 1423.] That night, the unhappy king ended his

MEXICAN PRIEST.

life by hanging himself in his cage by his girdle and thus perished Chimalpopoca, third king of Mexico, in or about the year 1423.

His reign had lasted about thirteen years, during which he had gained some victories over his enemies, and had, in the eleventh year, brought into his capital two great stones of sacrifice, one for ordinary prisoners, and one for gladiatorial combats.

The Mexicans lost no time in electing another king, who should be better qualified to cope with the tyrant; and this time they chose the brave Itzcoatl, a man of war from his youth, who had commanded the Mexican armies for thirty years.

In the meantime, Nezahualcoyotl, Prince of Tezcoco, had fled from Azcapozalco, by crossing the lake in a canoe with strong rowers. The tyrant organized a swift pursuit, but the prince succeeded in escaping his enemies, and in visiting all the important tribes in the valley, even penetrating to the province of Tlascala. Nearly all had become disgusted with the usurper, Maxtla, and promised aid to the prince in a great revolt against him. Aided by these allies he soon captured Tezcoco and several other cities once belonging to the ancient kingdom.

The King of Mexico, Itzcoatl, sent an embassador to congratulate him on these victories, and to assure him of the assistance of the Mexicans at the time when the final assault should be made on Azcapozalco.

This mission was an extremely difficult undertaking, for, though Tezcoco and Mexico were only fifteen miles apart, the roads and the lake were closely guarded by the tyrant to prevent communication between his foes. It was entrusted to the bravest man in all Mexico, a son of the former king, Huitzilihuitl, called Montezuma, who, by his invincible courage, had obtained the name of Ilhui-camina, or "Archer of Heaven." He succeeded in delivering his message, but in returning was captured by the troops of Toteotzin, lord of Chalco, and condemned to death. Through the humanity of his jailer he was allowed to escape, and returned to Mexico where he was received with great rejoicings.

[A. D. 1425.] The populace of Mexico were terrified at the prospect of a war with the tyrant, Maxtla, and tried to dissuade their king from such a desperate measure. It is related that finally they entered into a compact by which, if victory crowned their efforts, the common people were to be forever the slaves of the nobility, but if defeat, then the latter were to be sacrificed at their pleasure. This was the origin of the condition of things that prevailed at the coming of the Europeans, a century later, when the rich and powerful nobility dominated over a servile, degraded people.

A declaration of war was sent to King Maxtla, and again no one could be found to undertake this dangerous mission but Montezuma. It was only four miles from capital to capital, but nearly all the way through the enemy's lines. On his return, having' reached a position of safety, he taunted the guards of the tyrant with negligence in having allowed him to escape, and boasted that he would soon return and destroy them all. They rushed upon him to kill him, but he slew two of them, and then retreated rapidly to Mexico, conveying to the trembling inhabitants the declaration of war.

There is no more brilliant figure in Mexican history than this dauntless Indian, the first and the greatest Montezuma, risking his life in the cause of his people. Word was at once sent to Nezahualcoyotl to join his troops with the Mexicans, and the next day the Tepanec army—King Maxtla's—appeared in the field, adorned with gold and feathers, and shouting in anticipation of victory.

Knowing that upon their bravery the fate of their respective nations depended, each army attacked the other with terrible fury. King Itzcoatl led the Mexicans, having a little drum on his shoulder, by the sound of which he gave them signals for attack. At the close of a long day's fighting the Mexicans were about to give way, and had already promised the Tepanecs to sacrifice their nobles and generals to appease their wrath, when Montezuma rushed upon the opposite leader, and by a furious blow laid him lifeless on the field. This turned the tide of battle, and the Tepanecs fled to their city, pursued by the Mexicans and Tezcocans. The next day the battle was renewed, the city was taken, and the Tepanecs dispersed in every direction. King Maxtla was found hidden in a temazcalli, or vapor bath, and killed, and his body cast into the fields. By this victory, which occurred in the year 1425, just one century after the foundation of Mexico—Tenochtitlan—the Mexicans obtained the ascendency in Anahuac; thenceforward they were its actual masters. Azcapozalco, the Tepanec capital, was razed to the ground, and in the future was used as a market-place for slaves.

The King of Mexico held the people to their contract, by which they had agreed to cultivate the lands for the generals and nobles, to build their houses, and to carry for them their arms and baggage when they went to war; they were virtually their slaves. After the victory, the united armies marched around the valley, subdued all disaffected and rebellious tribes, and ended by entering Tezcoco, and placing Nezahualcoyotl upon the throne of his ancestors, from which he had been debarred by Tezozomoc and Maxtla for fifteen years. With this act was completed the restoration of the Chichimec monarchy, although its dominion was restricted, whereas before it was unlimited. The balance of power was held by the Mexicans, over whom reigned Itzcoatl.

It must have been a great temptation to the Mexican king to make himself Emperor of Anahuac, and prevent his ally from ascending the throne of Tezcoco, when he had it so fully in his power. Instead of this he showed himself a monarch truly great, by considering the general welfare and the claims of others before his own aggrandizement. He divided the territory of Anahuac into three kingdoms, placing a surviving son of Tezozomoc over the Tepanecs, with his capital at Tacuba. Nezahualcoyotl's capital was Tezcoco, east of the great lake; while Mexico, ruled over by Itzcoatl, lay between the two,—mistress of the valley and arbiter of its destinies. The many feudatories, or petty lordships, were placed either under the control of one or the other of the three, and peace for awhile reigned again in Anahuac. This triple alliance took place in the year 1426, or, according to some authorities, in 1431.