Archaeologia/Volume 38/Observations on a Grant of an Advowson of a Chantry to a Guild in 34 Henry VI

X. Observations on a Grant of an Advowson of a Chantry to a Guild in 34 Henry VI., exhibited by Joseph Jackson Howard, Esq. F.S.A. By Weston Styleman Walford, Esq. F.S.A.

Read March 17, 1859.

The Deed exhibited this evening by Mr. Joseph Jackson Howard has appeared to me sufficiently interesting to justify a few remarks on its contents. It bears date the 7th of August 1456 (34 Hen. VI.). By it Richard Acreman granted to John Oudene, master of the fraternity or guild of St. George of the Men of the Mystery of Armourers of the city of London, to John Ruttour and William Terry, the wardens, and to the brothers and sisters of the same guild the advowson of or right of presenting a chaplain to the chantry which Joan, formerly the wife of Nicholas de Wokyndon, Knight, founded at the altar of St. Thomas the Martyr in the new work of the cathedral church of St. Paul, London, viz. on the north side of the same church; which altar was, at the time of this grant, placed in the chapel then commonly called the chapel of St. George within the said church, in which chapel the said guild was then lately founded and established by King Henry VI.: this advowson the said Richard Acreman had of the grant of Thomas Coburley and Thomas Burghille, who had it (inter alia) of the gift of Richard Bastard of Bedford and Isabella his wife, who was kinswoman and heiress of the said Nicholas de Wokyndon. The deed was witnessed by William Marwe, the Mayor of the city of London, and John Yonge and Thomas Ouldegreve, the Sheriffs.[1] Appended by a label is the seal of Richard Acreman on red wax; it is circular, one inch in diameter, and bears an escutcheon charged with three pallets and on a chief as many mullets pierced; the legend is Sigillum ricardi akerman, in black letter. Though this is a good heraldic coat, there is nothing to indicate the rank or position in life of the bearer; nor do I find him mentioned elsewhere, or the coat ascribed to any one of the same surname. It may have been one of the many coats of arms met with on medieval seals, which, owing probably to an early failure of the issue of those who bore them, have never found their way into any of our ordinaries or heraldic collections. The surname, Acreman, having been derived from the occupation of those originally so called, may be found in various localities, without any ground for inferring consanguinity. In a few manors a small class of tenants of the humblest grade appear to have been called Acremen or Akermen, but the word had evidently a more extensive signification. Acre or Aker, in early times, did not mean any definite quantity of land, but, like Ager in Latin, was equivalent to field or plot of land; and it was the same in Anglo-Saxon and German. Acremen were, in our early English, fieldmen, men employed in agricultural labor, i.e., in modern language, husbandmen. At that time free laborers were few, and money wages rare: the demesnes of a manor, those parts which the lord retained in his own hands, were cultivated almost exclusively by men attached in various degrees of serfdom to the soil, who were allowed to occupy for their own benefit small pieces of ground, at low and sometimes almost nominal rents, and on the produce of those plots they chiefly subsisted. Such tenant-laborers were distinguished by several designations. Some rendered more days' work per annum than others, and some only certain kinds of work. Akerman occurs, as a surname, several times in the Hundred Rolls, under Cam- bridgeshire and Oxfordshire, chiefly among the villani, cotarii, and the like. The name is found also more than once in the Rent-roll of the Abbey of Malmesbury, of the 12th Edward I., printed in the Archæologia, XXXVII. p. 273; in one place (p. 283) Akermanni denotes a class of inferior tenants, and in another (p. 294) some persons are so called without any land or rent being mentioned in connexion with them. The name is found most commonly on lands held under religious houses of Anglo-Saxon or, at least, of very early foundation. Many of the tenants employed in cultivating the soil held their pieces of land and cottages at the will of the lord; and these became the copyholders of later times. Long before the date of this grant, as is well known, surnames had, with few exceptions, ceased to be any indications of the social positions of those who bore them; and, doubtless, Richard Acreman occupied a place in society to which his ancestors who acquired the surname never aspired.

The Armourers were one of the smaller companies of the city of London, yet the above-mentioned guild was not, I conceive, a trade guild. Most of those associations of artisans combined with the regulations respecting their craft or mystery others that made them partake also of the nature of the religious guilds which were then so numerous, and resembled benefit clubs in modern times;[2] but I think we shall see reason to believe, that this fraternity or guild of St. George was in reality a religious guild, though there may be some obscurity about the matter.

Such guilds had for their objects to promote peace and goodwill among the members, to assist the sick and unfortunate among them, to provide for the attendance of and offerings by the members at the funerals of those who died, and, what was then esteemed of far more importance, to secure perpetual masses and prayers for the repose of their souls. Many guilds of this class admitted women, and others allowed the widows of brethren to share in the benefits; which accounts for the mention of sisters as belonging to the guild of the men of the mystery of armourers. We may presume that the especial object of the guild in purchasing the above-mentioned advowson was to secure permanent means of obtaining such masses and prayers for the souls of deceased brothers and sisters; for that had then become a matter of some little difficulty. A few observations, explanatory of this state of things, may not be thought irrelevant, as they will render the purpose of the deed exhibited more intelligible.

After the doctrine of purgatory and the efficacy of prayers and masses for the dead had taken possession of the public mind, it had great influence in divers ways, and various were the means resorted to for procuring those supposed benefits. It was necessary to propitiate the living in order to induce them thus to serve the dead. Monasteries were founded or enlarged to secure these advantages for the benefactors; and kings and other influential persons were included in the prayers and masses so purchased to obtain their patronage and protection. From a like motive were churches occasionally erected, but more frequently were chantries founded in existing churches. Not a few of the aisles of parish churches were additions made for purposes of this kind. How far such practices might have gone, but for impediments of a legal nature, it were impossible to say. As is well known, statutes prohibiting the devoting of land to these and similar uses were enacted early in our national history, especially that de religiosisin the 7th Edward I., making the licence of the King and other chief lords necessary to the validity of such donations, or gifts in mortmain as they were called. The King and other great feudal lords were materially interested in the matter, as they lost by these endowments many advantages which would otherwise have accrued to them, not only military and other services, but also the wardships and marriages of heirs, and the pecuniary payments that became due on the deaths of tenants and the alienations of the lands. Whether from political considerations or less worthy motives I will not pretend to determine, but the cost of obtaining from the Crown the requisite licence for such gifts became after a while so great as to amount almost to a refusal; and as land was, we must remember, in those days the only kind of property from which a permanent income was derivable, it was a great obstacle, where perpetual masses were desired, not to be able to provide for them by gifts of land or rents. This led to other expedients being devised to accomplish the same ends. One of them was to pay down a sum of money to some religious house on security being given that a priest should celebrate masses there for the deceased, either for a certain time or for ever, as the bargain might be. The Paston Letters afford an example both of the difficulty and the remedy, almost contemporaneous with the deed exhibited. Sir John Fastolf, who was desirous of founding a college of priests to pray for his soul, wrote, about 1457, to his cousin John Paston, to move the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Winchester [for their influence with the King], that he might have a licence to amortise without any great fine, in recompense of his long service to the King and his father, which had never been rewarded; and since he intended to make the King founder and ever to be prayed for, and to have prayers also for his right noble progenitors, his father, and uncles, he (Sir John) thought he ought not to be denied his desire. The letter in reply, which was written by his nephew Henry Fylungley, informed him, that John Paston and the writer (who was also a lawyer) had communed together as touching the college, and that too great a good (i.e. sum) was asked for the licence, for they asked for every C. marks that he would amortise D. marks; and he proceeded to acquaint Sir John that Lady Abergavenny[3] had, in divers abbeys in Leicestershire, vij. or viij. priests singing for her perpetually by his brother Darcy's and his uncle Brokesby's means, for they were her executors; and they accorded for money, and gave CC. or CCC. marks, as they might accord, for a priest; and for the surety that he should sing in the same abbey for ever, they had manors of good value bounden to such persons as pleased the said Brokesby and Darcy, that the said service should be kept; and for little more than the King asked them for a licence they were through with the said abbots; and the writer held this way as sure as the other.[4] Such arrangements with religious houses to secure masses for deceased persons became probably not uncommon, in consequence of the difficulty and expense of procuring a license to put lands in mortmain for endowing a chantry. Two deeds for effectuating bargains of the kind with abbeys in 1503 and 1511 are printed in Madox's Formulare Anglicanum.[5]

But all these modes of obtaining the benefit of such prayers and masses were open only to the wealthy. The great body of the people had not individually the means of providing religious observances for the repose of their souls, and would have felt themselves in a very melancholy predicament, had not some method been devised for securing to them the consolation of having taken such precautions for their relief in purgatory. They formed at an early period, and very generally, those associations called fraternities or guilds of the religious kind above mentioned; a practice which had existed to some extent from Anglo-Saxon times. Each of the members contributed a small sum annually to provide a priest to say masses for their souls after death; and they also agreed to attend and offer at the funerals of deceased members; which was regarded as another great advantage at a time when recourse was had to all kinds of contrivances for obtaining a few pater-nosters or aves while the soul was supposed to be in a temporary state of suffering, and capable of being so relieved. For the prayers of laymen were deemed efficacious, as well as those of ecclesiastics; whence the poor beadsmen and women provided by some guilds, and maintained on certain eleemosynary establishments, and also the earnest invocations on sepulchral monuments, that the passers-by would thus contribute to the repose of the souls of the deceased. These associations became very general, not only in cities and towns, but also in villages, some having several of them, and few being without one.[6] In many country parishes portions of the guild-houses or guild-halls still exist near the respective churches, and retain their name, which has been a puzzle occasionally to persons who were not aware of the nature and prevalence of such fraternities. The guild-house was generally hired, but some of these guilds were enriched by donations and legacies, and purchased lands and houses; and hence the substantial buildings which here and there yet testify to their existence. So popular were they, and so beneficial were they deemed, that even princes and nobles, as well as other wealthy persons of both sexes, were glad to join them, as the ready means of securing for their souls, not only perpetual masses, but also prayers and offerings of a larger number of persons than any one religious house would ordinarily furnish. They had also their annual feast-days, and their processions with livery-hoods, badges, banners, and music, to make them agreeable to the commonalty.[7]

Many of these guilds, though they must have had at least a royal licence, for without it they were not considered legally established, do not appear to have been incorporated; but that which is mentioned in the deed exhibited had, about three years before the date of it, obtained this privilege by the favor of King Henry VI. Its origin and nature may be learned from the charter, which is dated the 8th of May, 31 Hen. VI. (1453).[8] The recital informs us, that the Men of the Mystery of Armourers of the city of London and their predecessors had, for a long time previous, an intimate and brotherly love; in so much that they, earnestly desiring to prosper and be increased, had begun to make, found, and establish, to the praise and honor of God and of the glorious martyr St. George, a fraternity or guild among themselves, and to burn a certain wax light to the praise and honor of the famous martyr in his chapel within the cathedral church of St. Paul, London, at certain times before the image of the same martyr, and had piously, peaceably, and quietly offered, found, and charitably maintained and continued certain divine services, ecclesiastical ornaments, and other works of charity and piety there, for a long time past, yearly to the honor of the same martyr; and that they, fearing the said fraternity not to be rightly and lawfully founded and established according to law, had most humbly requested the King, that he would graciously favor their pious and devout intentions in that behalf. The King, being willing to provide that the said fraternity or guild might continue to future ages, and in order to found such fraternity or guild from himself, through the devotion which he bore and had towards the said glorious martyr, and assuming and being willing to be called the founder of that fraternity or guild for ever, to the praise, glory, and honor of Almighty God and the most glorious and undefiled Virgin Mary, mother of Christ, and also [to the praise, glory, and honor] of the blessed George, the famous martyr, did of his special grace, and of his certain knowledge, found, create, and establish a certain fraternity or guild of his liege men of the said Mystery of Armourers, and of all others faithful in Christ willing to be of the same fraternity or guild, to find and maintain one chaplain to perform divine service daily for his (the King's) state and the state of the brothers and sisters of the same fraternity or guild while he lived, and for his soul and the souls of the brothers and sisters of that fraternity or guild after he had departed this life, and the souls of all faithful people deceased; and also [to find and maintain] certain poor persons of both sexes in like manner to entreat and pray the Most High for ever for the state and souls aforesaid in the aforesaid chapel. The charter proceeded to create the fraternity or guild a corporation by the name of the Fraternity or Guild of St. George of the Men of the Mystery of Armourers of the city of London, and to empower them to receive and accept any persons to be such chaplain and poor persons, according to the rules of the more noble and worthy part of the said brothers and sisters and their successors, to be in that behalf made. It then authorised them to appoint a master and wardens from time to time, and in the corporate name to purchase and take lands, tenements, rents, and other possessions in fee, and also to plead and be impleaded in that name, and to have a common seal, and to hold meetings, and to make rules and orders, as well for the said chaplain and poor persons, as for the good government of the said fraternity or guild; and finally there is a licence to purchase lands, tenements, rents, and other possessions to the extent of 10l. per annum towards the maintenance of the said chaplain to perform divine service in form aforesaid.

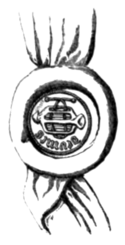

Strype and others appear to have understood this charter as incorporating the Company of Armourers; which is hardly consistent with the language of it. The company had existed long before; and the charter is confined to the establishment of a guild among themselves (de se), which they had commenced without the requisite royal licence, and which is throughout treated as a guild of the religious kind exclusively. The charter even seems to have contemplated persons becoming members of the guild, who did not belong to the company. The Armourers are in possession of a silver matrix of a seal, apparently of the early part of the fifteenth century, which has been supposed to be the common seal of the guild, made on its incorporation by this charter; but if I have assigned the correct date to it, this could not have been the case. A woodcut of an impression is given in the margin. It will be seen to be circular, about 158 inch in diameter; the device is St. George on foot piercing the dragon with a spear, between two escutcheons, that on the dexter being charged with two swords in saltire, which still form part of the arms of the company, that on the sinister with a plain cross, doubtless for St. George, and each escutcheon ensigned with a helmet respecting the other; the legend is in black letter, and read in extenso is Sigillum commune artis armurariorum civitatis londonearum. One would have expected that the seal of the guild, made on its incorporation, if it bore any name at all, would have borne its corporate name or, at least, a legend in accordance with that name; but this legend makes the seal look like a seal of the company, St. George being their patron saint. A charter for founding a religious guild of St. George, at Norwich, in 5 Henry V., as given by Madox in his Firma Burgi,[9] is very like that in question; and so is the charter of 26 Henry VI. for founding the Haberdashers' guild of St. Katherine, judging from the description given of it by Herbert;[10] whereas the charter of 17 Henry VI. for founding the Drapers' guild of St. Mary, and that of 20 Edward IV. for founding the Clothworkers' guild of St. Mary, both of which were of the mixed kind, were materially different, extending as well to the mystery as to the guild.[11] The charter of the Fishmongers' Company in 11 Henry VI. shows how such instruments were expressed when the incorporation had relation to the mystery only.[12]The ordinary practice of these guilds was to hire a priest to he their chaplain and say the requisite masses and prayers at some particular altar. He was often a chantry priest that already had similar duties to discharge. But we have in the deed exhibited evidence of a less common expedient, one of which probably few traces have come down to us, the purchase of the advowson of or perpetual right of presentation to a chantry already existing. The issue of the founder should seem to have failed, and the remote heir, feeling probably but little interest in the matter, or yielding perhaps to the importunity of a husband who felt none, joined with him in alienating this advowson. By the acquisition of it the guild obtained virtually a permanent chantry 'of their own, including priest, altar, and endowment; for they, no doubt, arranged with the clerk whom they presented, that he should be also their chaplain, and should say from time to time at the same altar the requisite prayers and masses for deceased members of the guild. It may be thought that for a purchase of this kind no licence was required ; but the fact was otherwise. As early as the time of Richard II. these guilds had become purchasers and donees of lands, and it should seem even of advowsons; and when in the fifteenth year of that king's reign the Statute of Mortmain (7 Edward I.) was extended to lay corporations, purchases of lands and advowsons by guilds or fraternities were expressly subjected to the same restrictions. In the instance before us, the licence contained in the charter to purchase lands, tenements, rents, and other possessions was most likely considered to be sufficient, and to have rendered any further licence for the acquisition of the advowson unnecessary.

The last priest of this chantry was Robert Shuter. He was presented in the 16 Henry VIII. by the master and wardens, not of the guild, but of the craft or mystery of the Armourers, with the consent of the whole body of the said mystery. What had intervened to account for this does not appear. The bond and indenture executed on that occasion are in the possession of the company. By the former Shuter became bound to the master and wardens of the mystery in 100l.; by the latter, which was made between them and Shuter, his duties were prescribed, and the bond was to become void on the performance of them. Nothing is said in it of the guild, though he was to give attendance on the master and wardens of the mystery unto all such burials and obits as they should go unto in their livery. He engaged to keep and maintain all books, chalices, vestments, jewels, and other ornaments delivered to him belonging to the chantry, an inventory of which is annexed to the indenture, and, at his departure, to re-deliver them to the master and wardens. They were of the usual kind for an altar, though some of the vestments were richly ornamented. There is only one hook mentioned in the inventory, and that is a great mass book of vellum "lymmbde" with gold. Nor is there more than one chalice, but it is worthy of notice as having on it two coats of arms; one is said to have been a shield of red with a white lion with a crown on his head of gold, which we shall presently see was the coat of Sir Nicholas de Wokyndon, the founder; the other had a field red with three flours de lis blue, which is false heraldry, and I cannot identify it; but it may have been intended for the arms of his wife, or, more correctly speaking, those of her father. What the jewels were is not quite clear: probably they were the chalice, the paten (which was enameled with the Trinity), two corporases, the pax, and the richest parures of the vestments; for there was a great chest of iron with a bar running through with a lock, to keep the jewels of St. George in. There was another chest with a lock, but no key, and therefore not likely to have been used for keeping any thing of value.

In the deed exhibited the chantry is stated to have been founded by Joan, late wife of Nicholas de Wokyndon, Knight, but it appears to have had its origin in his will. We read in Dugdale's History of St. Paul's,[13] where he speaks of some chantries in the new work on the north side, that in the "15th year of King Edward II. did Nicolas de Wokyndon, by his testament, devise 100s to the before specified building called the new work, in regard that in it he intended to be buried; and, to maintain a chantry priest therein celebrating for his soul, bequeathed certain lands lying in the parish of St. Olaff (London) to the dean and chapter of this Church; and moreover, for the like consideration, gave an 100l. to purchase rents for the finding of another chantry priest at the altar of St. Thomas, and to the keeping his obit and the obit of Joan his wife for ever." It appears by deeds in the possession of the Armourers' Company, that his widow, who was his executrix, purchased the rents required, and endowed the chantry at the altar of St. Thomas with them in January 1320-1, reserving the advowson of the chantry to herself for her life, and afterwards to the heirs of her late husband. This reconciles what is said of her having been the founder with that part of the deed which traces the advowson from his heir; it shows, at the same time, that the 15th Edward II. mentioned by Dugdale as the date of his will must be a mistake; probably it should be the 13th Edward II., which regnal year ended on the 7th of July, 1320. The altar of St. Thomas was in the new work on the north side of the cathedral, where the testator intended to be buried. He had most likely made some arrangement with the Dean and Chapter for that purpose.

Of Sir Nicholas de Wokyndon and Joan his wife little is known. His family derived their name from North Wokyndon, or Ockendon as it is now called, in Essex, in which parish, and in Chadwell that is near it, they appear to have held property from an early period under the bishops of London.[14] His father was, in all probability, the Sir William de Wokyndon who witnessed the grant by Sir William le Baud in 1275 to the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul's of a buck and a doe annually,[15] which led to a remarkable procession and an offering of a buck and a doe every year in St. Paul's until the time of Camden and Stow, both of whom speak of having seen some part of the ceremony.[16] The confirmation of that grant by Sir Walter le Baud, son of Sir William, in 1302, was witnessed by Sir Nicholas de Wokyndon himself and some other knights of Essex.[17] He was evidently a person of some importance in the county; for, though I do not find him among the King's tenants in capite, he was enrolled for military service in Essex in 24 Edw. I. (1296), and summoned to serve against the Scots in 29 Edw. I. (1301);[18] and he and his consort, doubtless the above-mentioned Joan, were invited among the nobility and other distinguished persons to attend the coronation of Edward II. and his Queen in 1308.[19] He was one of the knights returned for the perambulation of the forests in 1316, and was, in the same year, one of the conservators of the peace.[20] He and also a cadet of the family named Thomas de Wokyndon, probably a brother, appear in the Roll of the Arms of Bannerets in the time of Edward II. under Essex; where his own arms are given as, "de goules a un lion de argent corone de or," and those of Thomas "de goules a un lion barre de argent e de azure." He died, it should seem, on the 8th of May, 1320; for on that day was his obit to be kept, as appears by the endowment, which we have seen, took place by the grant of his widow in January 1320-1.[21] He left no male issue; an only daughter named Joan married Thomas de Halughton, and had issue a son, Sir Nicholas de Halughton, who died in 1338, seized of estates at Ockendon Chadwell, and other places in Essex. His wife, whose name was Margaret, survived him. He probably died young, for his heirs were two infant daughters, Margaret and Joan, of the respective ages of two years and one year;[22] a supposed brother and nephew, both named Thomas, mentioned by Morant, are more likely to have been an uncle and cousin. Margaret (the daughter) married, successively, Roger de Northwode, John Barry, and Walter Gray; Joan married Thomas de Asheton.[23] Whether either of them left issue does not appear; nor can I trace any connexion between them and Isabella wife of Richard Bastard of Bedford, who is called in the deed exhibited consangninea et hæres of Sir Nicholas de Wokyndon, and should seem to have succeeded in some way to the advowson of the chantry founded pursuant to his will. She may have been, and probably was, some relation too remote to have felt any particular interest in the founder, and was therefore content to part with the right of presenting a priest to his chantry. She and her husband were both living in 1442; for the deed whereby they conveyed the advowson and other property to Coburley and Burghille bears date the 20th of June, 20 Henry VI.[24] She is not therein called consanguinea et hæres of Sir Nicholas do Wokyndon, or otherwise described as in any manner related to him; but the other property comprised in the deed is the Wokendon Fee in Terling, Essex, which, we may reasonably suppose, derived its name from having been in his family, though Morant has not traced its history so far back. At the date of that deed 104 years had elapsed since the death of Sir Nicholas de Halughton; and there had, therefore, been ample time for several devolutions of the property before it came to Isabella.

It may have been observed that the name of her husband, Richard Bastard of Bedford, is remarkable. Bastard was a name well known in Devonshire, and the names of Coburley and Burghille possibly, as well as Acreman, may be referable to the West of England; but why is he called of Bedford? No other person mentioned in the deed has the place of his or her residence subjoined; nor can I discover that there was then at Bedford any family or person of the name of Bastard. If, however, John Duke of Bedford, who died in 1435, had an illegitimate son named Richard whom he recognized, that son would, in all probability, have been called Richard Bastard of Bedford; for there was at that time a practice, not only in France, but also in this country, of thus designating illegitimate sons of noblemen. Contemporary with this Richard were John Bastard of Clarence, John Bastard of Somerset, a Bastard of Salisbury, and Thomas Bastard of Falconbridge, sons respectively of Thomas Duke of Clarence, John Beaufort Earl of Somerset, Richard Neville Earl of Salisbury, and William Neville Lord Falconbridge. Should it be suggested that the i at the end of Bastardi in the deed exhibited is in reality a mark of contraction used after d to supply a final e, besides that it more resembles an i, all doubt on this point is removed by the original deed by which this Richard and his wife conveyed the advowson to Coburley and Burghille. On examining that, I found he is there called Ricardus Bastardus de Bedford' Armiger.[25] Now, had Bastard been a family surname in either case, it would hardly have been latinized; for such was not then the practice in preparing deeds; add to which, the name of no other person mentioned in the last-mentioned deed is followed by that of the place of his or her residence. The seal of Richard remains attached, and a woodcut of it is given in the margin. It will be seen to be a small one with a device and motto, but no name; and consequently it affords no evidence as to who or what he was. Under all the circumstances, I think we may accept this Richard as a long-forgotten illegitimate son of John Duke of Bedford, uncle of Henry VI. and brother of the before-mentioned Duke of Clarence. I have sought in vain for any mention of such a son of his elsewhere. It is not at all improbable that an illegitimate son of that prince, even though recognized by him, should have passed into oblivion, if he did nothing to distinguish himself. There was an Earl of Bedford a few years earlier, who, in point of time, might possibly have been the father of this Richard, viz. Ingelram de Coucy, who came to this country as a hostage from France in 1303, and, having married Isabella, one of the daughters of Edward III. was created by him Earl of Bedford. On the renewal of the war with France in 1309, he went into Italy; but eventually returned to his own country, and died in 1397. It seems to me far more likely that this Richard, who was living and of full age in 1442, should have been the son of John Duke of Bedford who was born in 1390, than of Ingelram de Coucy, who does not, I believe, appear to have been in England after 1369, which was 73 years before the date of the conveyance to Coburley and Burghille. The fact of John Duke of Bedford not having married till 1423, when he was 33 years of age, makes the supposition of an illicit connexion of which Richard may have been the issue by no means improbable. So much reason is there, in my opinion, for adopting this view of the name, Richard Bastard of Bedford, that, had the deed exhibited been in other respects of an ordinary kind, I should have thought the occurrence of this name in it rendered it worthy of being brought to the notice of the Society, as a contribution to the genealogy of the House of Lancaster.In conclusion, I have to acknowledge my obligations to Mr. J. J. Howard for all the information that I have derived from the archives of the Armourers' Company, specially for the opportunity of inspecting the various deeds to which I have referred. The inrolment of the charter of the guild in the original language I examined at the Record Office.

- ↑ The original deed, with the contractions extended, except a few that may be doubted, is as follows: "Sciant presentes et futuri, quod ego Ricardus Acreman tradidi, dimisi, et hac presenti carta mea confirmavi Johanni Oudene, Magistro Fraternitatis sive Gilde Sancti Georgii de hominibus Mistere Armurariorum Civitatis London', Johanni Ruttour et Willelmo Terry, Gardianis Fraternitatis sive Gilde prediete, ac Fratribus et Sororibus ejusdem Fraternitatis sive Gilde totam illam Advocacionem ac presentacionem Capellan' illius Cantarie quam Johanna, quondam uxor Nicholai de Wokyndone, Militis, fundavit ad altare Sancti Thome Martiris in novo opere ecclesie cathedralis Sancti Pauli London', scilicet, ex parte boriali ejusdem ecclesie; et quod quidem altare modo situr (sic) in Capella nunc vulgariter nuncupata Capella Sancti Georgii infra (sic) ecclesiam predictam; in qua Capella dicta Fraternitas sive Gilda per Dominum Henricum Regem Anglie Sextum modo fundata, formata, erecta, et stabilita est; quam quidem Advocacionem ac presentacionem ego predictus Ricardus nuper habui ex tradicione, dimissione, et confirmacione Thome Coburley et Thome Burghille; et qui quidem Thomas et Thomas eandem Advocacionem ac presentacionem preantea habuerunt, inter alia, ex dono et feoffamento Ricardi Bastardi de Bedford' et Isabelle uxoris sue, consanguinee et heredis predicti Nicholai de Wokyndone; Habendam et tenendam predictam Advocacionem ac presentacionem Capellan' Cantarie predicte prefatis Johanni Oudene, Magistro, Johanni Ruttour et Willelmo Terry, Gardianis, ac Fratribus ct Sororibus predicte Fraternitatis sive Gilde, et successoribus suis imperpetuum. In cujus rei testimonium huie presenti carte mee sigillum meum apposui. [Hiis testibus,] Willelmo Manwe tunc Maiore Civitatis London', Johanne Yonge et Thoma Ouldegreve tunc Vicecomitibus ejusdem. Datum London' septimo die mensis Augusti anno Domini millesimo quadringentesimo quinquagesimo sexto, et anno regni Regis Henrici Sexti post conquestum Anglie tricesimo quarto." Under the fold is "Ecton," and also "r' coram M' et Abraham viijo die Augusti Anno xxxiiijto Henrici vjti." Indorsed is "Ista carta lecta fuit et irrotulata in hustengo London' de communibus placitis tent' die lune proximo ante festum Sancti Kalixti Pape anno regni Regis Henrici Sexti post conquestum tricesimo quinto. Spycer." And a little lower down is "Ista carta fuit lecta, sigillata, et registrata in registro Reverendorum dominorum Decani et Capituli ecclesie Cathedralis Sancti Pauli London' primo die mensis Aprilis anno Domini millesimo quadringentesimo sexagesimo nono, tempore magistri Rogeri Radclyffe Decani. Percy."

- ↑ Similar fraternities are still common in Roman Catholic countries.

- ↑ Her will is given in Dugd. Baronage, i.p. 240, and Testamenta Vetusta, p. 224. She was a daughter of Richard and one of the sisters and co-heirs of Thomas Earl of Arundel; her husband was William Beauchamp, Lord Abergavenny. She died in 1434. The writer of the letter, Henry Fylungley, was one of her legatees. The mode here mentioned of providing masses for her soul was not specially directed by the will.

- ↑ Vol. I. Letters XLI. XLII.

- ↑ See Nos. DXCVII. DXCIX.

- ↑ Many of the piscinæ; found in the naves and aisles of churches once belonged to guild-altars.

- ↑ Two wealthy guilds at Cambridge, of which several distinguished persons were members, founded Corpus Christi College in that University. Some interesting particulars of those guilds are given in Masters's History of that college. See also on the subject of guilds of the religious kind Dr. Rock's Church of our Fathers, vol. ii. p. 395, and the works referred to by him, and Mr. Burtt's account of certain guilds at Walsingham, in the volume containing the Proceedings of the Archæological Institute at Norwich, in 1847.

- ↑ It is inrolled 31 Hen. VI. secunda pat. m. 12. An old translation into English is in the possession of the Armourers' Company.

- ↑ Page 24.

- ↑ Vol. ii. p. 536.

- ↑ See Herbert, vol. i. p. 482, ii. p. 649.

- ↑ Herbert, ii. p. 116.

- ↑ Second edit. p. 32.

- ↑ Morant's Essex, i. pp. 102, 230.

- ↑ Dugdale's History of St. Paul's, p. 17. Stow's London.

- ↑ Camden's Britannia, edit. 1590, p. 330. Stow's London.

- ↑ Dugdale and Stow, ubi supra.

- ↑ Parl. Writs, i. pp. 273-4, 352.

- ↑ Rymer, ii. p. 31.

- ↑ Parl. Writs, ii. p. 161; App. p. 103.

- ↑ Deeds in the possession of the Armourers' Company.

- ↑ Writ and Inq. p. m. 13 Edw. III.

- ↑ Morant's Essex, i. 230.

- ↑ See a copy of that deed in a subsequent note.

- ↑ The original deed, with the contracted words extended, except a few that are doubtful, is as follows: "Sciant presentes et futuri, quod nos Ricardus Bastardus de Bedford' Armiger et Isabella uxor mea dedimus, concessimus, et hac presenti carta nostra confirmavimus Thome Coburley et Thome Burghille omnia teraset tenementa nostra cum homagiis, feodis militum, maritagiis, releviis, escaetis, heriettis, redditibus, et serviciis omnium tenentium, tam liberorum quam nativorum, de feodo nostro vocato Wokendone Fee in villa de Terlyng Crikkeshithe, in comitatu Essex, una cum Advocacione Cantarie Sancti Thome in ecclesia cathedrali Sancti Pauli, London', ex parte boriali, cum omnibus suis pertinenciis; Habenda et tenenda omnia predicta terras et tenementa cum homagiis, feodis militum, maritagiis, releviis, escaetis, heriettis, redditibus, et serviciis omnium tenentium, tam liberorum quam nativorum, de feodo nostro predicto, una cum Advocacione Cantarie predicts, ut supradictum est, cum omnibus suis pertinenciis, prefatis Thome Coburley et Thome Burghille, heredibus et assignatis suis, de capitalibus dominis feodorum illonim per servicia inde debita et de jure consueta, imperpetuum. In cujus rei testimonium huic presenti carte nostre sigilia nostra apposuimus. Hiis testibus, Thoma Basset gentilman, Roberto Buri, Johanne Rouchestre seniore, Johanne Rouchestre juniore, Johannu Spurne, et aliis. Datum apud Terlyng predict' vicesimo die Junii anno regni Regis Henrici Sexti post conquestum Anglie vicesimo." Two small seals on labels are appended; of the first a woodcut is given in the text; the device on the second appears to be a wolfs head erased, without any legend. The former from the legend, debines, should seem to have been intended as an enigma, and from the singularity of the object represented I apprehend it is likely to remain unsolved.

The conveyance to Acreman is also in the possession of the Armourers' Company. It is dated the 12th of March, 21 Henry VI. (1446), and by it Coburley and Burghille granted to Acreman, his heirs and assigns, the odvowson only. There are no witnesses. Two small seals are appended; one has on it a bird with the legend, Thomas Coburley: the other a hedge-hog with a legend obscure. The parties to the deed are the only persons mentioned in it, and no place of residence is subjoined to any of the names.

In addition to what has been said of the seal of Acreman appended to the deed exhibited, I may here mention, that the words of the legend are separated by sprigs of oak, as if he supposed the first syllable of the name to have been derived from Ac or Ake (oak) instead of Acre; and that round the impression are the marks of a plaited rush by which it was formerly protected from injury; a practice occasionally found exemplified in seals of that period.