Archaeologia/Volume 38/Observations on the Ancient Domestic Architecture of Ireland

Read March 10th, 1859.

Perhaps no country in the world possesses so complete a series, as Ireland, of Domestic Architecture, in the full meaning of the words, that is, of human habitations; it begins with the underground abodes and the beehive houses of the earliest inhabitants of the island (belonging to the same period as the Cromlechs and Cairns), and is continued almost without interruption to our own day. But, before any attempt is made to describe or to classify the existing remains of human dwellings in Ireland, it is necessary to call attention particularly to the geological formation of the country. The nature of the building materials, as is well known, exercises great influence everywhere upon the architectural character, but nowhere else is this so evident and distinct as in Ireland. With a few rare exceptions, such as unfortunately are Dublin and Belfast, and their immediate neighbourhoods, stone is every where abundant, and generally of the same quality, extremely hard and durable, but very difficult to cut or work in any way. A very large part of Ireland is an immense limestone plain, covered indeed in many places with extensive peat-bogs, but these are seldom very deep; in general the stone is very near the surface, and in many places it crops out. This limestone when broken up, and especially when burnt into lime and mixed with the peat, makes a very fertile soil. In many districts, especially in Galway, the surface is so much covered with loose stones of large size, that they have to be removed before the soil can be cultivated. These stones are generally of such a size and form as to be convenient for building purposes in their rough state, so that there is no need to cut them ; but when there is occasion for this, it is a very difficult and tedious, and therefore expensive, operation. In some parts of the country, as in the valley of Glendalough, stone is found in very large masses, which can be split horizontally into slabs without much difficulty, but it is extremely hard, and difficult to cut against the grain. It will readily be seen, from this short description of the building materials, that they must necessarily exercise great influence on the character of the buildings, more especially in early times, before the use of machinery, and when the tools were very inefficient.

In the districts where stone is found in large masses, so that abundance of slabs may be obtained of ten or twelve feet long, or even more, by one or two feet thick, and varying in width from one foot to three or four, it is perfectly natural that the buildings should have been erected of what is called Cyclopean masonry; for such masses were easily ranged in walls, and required no mortar. As it was difficult to obtain cut stone for the quoins or corners, it was more convenient to build a tower round than square; just as in Norfolk, Suffolk, and other chalk countries—where the usual building material was flint, and there was a scarcity of stone for corners—the towers were also built round. The great abundance of stone has also had another remarkable effect in Ireland, or at leass in many parts of it; for, stone fit for ordinary building purposes being found everywhere on the surface of the ground, and having only to be collected and used as wanted, it does not pay to pull down old walls for the materials, as is done in other countries; and when stone is to be had upon the spot people will not carry it half a mile. But, as wood was not equally abundant and was useful for fuel, every scrap of wood or thatch has commonly been burnt, and nothing but the stone walls left standing. The consequence of this is, that the surface of Ireland is covered with ruins of old buildings of all ages, from the cairns to the cabins deserted fifty years ago or only yesterday. Hundreds of cabins, abandoned in consequence of the great famine, are standing just as they were left, so far at least as regards the stone walls and chimneys; the wood and thatch have all been burnt, but it has not been worth any one's while to pull down the bare walls. This circumstance gives Ireland a very desolate appearance to strangers, but it is not in reality a proof of extreme poverty, as is often at first sight supposed.

The nature of the material also influenced the fashion and the details of the buildings in many other ways. The primitive houses were vaulted with a sort of rude dome formed by the overlapping of the ends of large stones, as in the Pyramids of Egypt; and the fashion of vaulting with rough stones, though gradually becoming less rude, was continued to a late period. The houses popularly attributed to the saints of the fifth and sixth centuries have vaults of a more advanced construction, and bearing considerable resemblance to those of the Pembrokeshire churches; but it is worthy of remark that in Ireland the churches are not generally vaulted, while the houses are. In those early examples, such as St. Kevin's in Glendalough and St. Columbkill's at Kells, the vault is at a considerable elevation from the ground, and had wooden floors under it, as in the castles or towers of the twelfth century and later.

The peculiar form of doorway with sloping sides and a flat lintel, which is quite an Irish fashion, seems also to have originated in the nature of the material. A similar form of doorway occurs in the Egyptian Pyramids, and in some other oriental buildings, and this may by some persons be considered as an evidence of the oriental origin of the Irish people; but that is not to our present purpose. In Ireland it is found in the cairns, as at New Grange, and in the Hill of Dowth, and is there formed simply of three long stones, not cut, but selected for the purpose, and the top inclined inwards in order to fit the lintel-stone more conveniently, and give it a longer bearing on the side stones. This is the case also at St. Kevin's house in Glendalough, which is of Cyclopean masonry. The same form was copied afterwards in cut stone, as in the round towers at Kells and Clondalkin; and it became a regular Irish fashion, continued both in doorways and windows when convenient at all periods down to the time of Elizabeth. It occurs in the tower-houses throughout the Middle Ages, and in Elizabethan work of dated houses at Galway.

The triangular-headed window is another feature which evidently has its origin in the material, and, although found in early work, is not confined to any period; it is one of the Irish fashions which may be traced from the earliest to the latest times, and, like the doorways before mentioned, is in itself no evidence of date; it occurs in many of the small churches, which, from their extreme plainness, may be of any period, as well as in houses and castles. A window with sloping sides and a round head, cut out of a single stone, is also of frequent occurrence, as at Ross, co. Galway. The very great thickness of the walls, in many instances, may also be attributed to the nature and the abundance of the material; and this rendered buttresses altogether unnecessary.

The peculiar tongue-shaped corbel, which is another Irish fashion throughout the Middle Ages, may perhaps also have been originally due to the material; it required less cutting, and the stone could be more easily trimmed into that form of corbel than any other.

Another point which must be considered in treating of houses in Ireland is the character of the people from the earliest period of history: they were pre-eminently a belligerent people, always fighting among themselves if not with their invaders. Accordingly, we find from primitive times that the idea of defence seems to have been always uppermost in the mind of an Irishman when building his house; the first thing to be considered was, how best to keep out an enemy. In the subterranean abodes and the bee-hive houses the entrance is so small and low that a man can only get in by crawling on his hands and knees, and would therefore be entirely at the mercy of any one within.[1] This is the case as well in the temples and tombs, as in the magnificent tumulus or cairn at New Grange, where the interior is richly ornamented with incised patterns; in the Hill of Dowth in the same immediate neighbourhood; in the subterranean habitation near Athenry; and I believe in all the early structures, whether intended merely for dwellings or for any other purpose.

Throughout the Middle Ages every house of any importance was a castle, that is to say, it was built in the form of a tower and fortified; but it was not the less a dwelling-house, since every manor-house throughout the country was built after the same fashion, and there were no other houses of any considerable size.

In consequence of the influence of these two great causes, the material and the character of the people, the architecture of Ireland has a very marked national character, different from that of any other people, yet bearing a certain resemblance in some points to that of Scotland, Wales, and Britany, though still distinct from all of them. Notwithstanding the strong national character, which no other country possesses in a more marked degree, though all countries and large provinces have to a certain extent a national or provincial peculiarity, the different styles of each century of the Middle Ages can be distinguished in Ireland as well as in other countries of Europe, though it is often difficult to make them out, in consequence of the extreme plainness and rudeness of the work. The square towers, which wore the usual habitations of the gentry in Ireland throughout the Middle Ages, whether English or Irish, are generally so very plain, especially on the exterior, that on a mere cursory observation they are commonly said to be all alike. This is, however, entirely a mistake; on examination no two of them are found exactly alike; the internal arrangements differ constantly; there is generally some little bit of ornament in cut stone somewhere, just enough to indicate the date; usually this is the tracery, or the arch in the head of the upper windows; but, besides this, the vault is sometimes over the ground floor, and sometimes nearly at the top of the tower, with wooden floors only under it; occasionally there are two vaults, or even three. In some instances the bed-rooms are numerous, occupying a third part of the tower, excepting at the top, where the state apartment usually occupies the whole space above the upper vault, having arrangements at one end for the servants, commonly near the top of the stairs, with recesses in the walls for various purposes, and almost invariably a drain for carrying off water which had been used. It frequently happens that a wall has been introduced at a period subsequent to the original erection of the tower, separating about a third part of it, evidently for bed-rooms. The battlements are frequently cut into corbie-steps, giving a ragged and picturesque appearance to the upper part of the towers; those at Jerpoint Abbey (see woodcut[2]) are good examples of this.

But to have a clear understanding of the domestic architecture of Ireland during the middle ages, it is necessary to include the religious houses, and to take the whole in chronological order, bearing in mind that every house was fortified, not excepting even the abbeys, which were as effectually protected as any houses or castles of the same period. By endeavouring to arrange a chronological series, and by offering a few specimens of each period, I hope to give a clearer idea of the whole than has hitherto been published.

Passing over the bee-hive houses of Kerry, the subterranean abodes, tombs, or treasuries, and the circular forts with low walls round them, as at Athenry, (more properly Athenree, the city of the Kings,) which belong to a primitive period too remote for our purpose, and, though some of them were probably dwellings, they can hardly be called houses, the earliest habitations, which come within our province, are the houses known by tradition as the houses of the saints; some of which may possibly be of the period to which they are assigned. One of the best authenticated of these, and the one where the building itself shows the best confirmatory evidence, is that popularly known by the name of St. Kevin's Kitchen, in the valley of Glendalough. The name is easily accounted for by its present appearance; but it is, in fact, a house of a very early period converted into a chapel in the twelfth century. It is recorded that a monastic establishment was planted in the valley by St. Kevin in the early part of the sixth century; and Irish antiquaries usually assign this house to that period. It may reasonably be doubted whether the Irish people were acquainted with the art of building with cut stone and mortar at that time, since Bede expressly tells us that, when the Romans left Britain, they advised the people to build a wall across the northern portion of the island, which was done, but they were obliged to make it of earth and sods only, because they had no artists capable of building it of stone; he also frequently mentions the manner of building of the Scots, as of wood, thatch, and wattles, or wicker-work only. There is no reason to suppose that the Irish were in advance of the Britons, and they were included under the general name of Scots. They may have piled up the rough stones which they found on the surface in various forms; but the arts of cutting stone, of burning it into lime, and of making mortar, imply a considerable progress in civilization. We may, however, conclude that the house called St. Kevin's Kitchen is one of the earliest buildings in Ireland, and belongs to a period anterior to the twelfth century, because it was altered into a chapel at that time. The original structure was a small oblong room of Cyclopean masonry, on which are a lofty and massive stone roof and vault;[3] at the springing of this is a ledge, which seems to indicate the position of a wooden floor, so that, there was an upper room under the vault, as in the towers of later date; and there is a small window in the east gable, to give light and air to this upper chamber. The head of the window of the lower room still remains; it is cut out of a single stone, and widely splayed within; the lower part of it was removed, when a round-headed chancel-arch was cut through the wall; and it seems pretty clear that this must have been done in the twelfth century, when a chancel, since destroyed, was added, and a vestry, which still remains, clumsily joined to the south-east corner of the original building: this vestry has a window of the usual character of the twelfth century, and the head of an earlier window, cut out of one stone, is used as old material in the rubble wall. The original building has a west doorway of the early Irish form, with a round arch above the lintel, leaving a small plain tympanum.[4] The upper part of the west gable has been cut off, and a round belfry-turret built upon it, resting partly on the wall and partly on the stone vault, as is the case in some of the Pembrokeshire churches, which bear considerable resemblance to this building. Similar massive stone vaults are common in the Channel Islands, and in Aquitaine and the Pyrenees, and also, probably, in most places where similar materials are found. The detached round tower is exactly of the same construction, and apparently of the same age, as the round belfry turret; they are within sight of each other, and may be easily compared on the spot. The detached tower belongs to the cathedral which forms one of the Seven Churches; it has Cyclopean masonry in the lower part of the walls, and small openings, like the round tower, in the upper part; a south doorway and east window have mouldings of the twelfth century; but these are of a different stone (said to be from Caen), and may be insertions. The round tower is 120 feet high, divided into six stories; it has a round-headed doorway, and there are small square-headed windows on each story, and four apertures for bells at the top, exactly like the turret of St. Kevin's, only considerably larger: it has lost the roof.The house which comes the nearest to this in apparent antiquity, is St. Columbkill's House, or rather St. Colomb's Cell, at Kells, co. Meath. This is another small oblong house, with very thick walls of rough stone, of various sizes and shapes, merely split, not cut. Some of the stones are three or four feet long, others smaller, all deeply bedded in mortar, with very wide joints. It has a stone roof, and a vault under it, with a space between the top of the vault and the outer roof, which is divided by two cross walls into three cells, with round-headed doorways from one to the other. These cells do not appear to have been large enough for habitation, and the only entrance to them was through a small square hole in the wall, more like a chimney-shaft than anything else. The original entrance to the house was of the early Irish form called Cyclopean at the west end, which is now walled up, and another cut through the wall on the south side; there is a fireplace in the south wall; the windows are small, with triangular heads; their position and other indications show that there was a wooden floor under the vault; there have indeed been two floors, hut whether both were original may be doubtful; the exterior is so much hid by ivy that the position of the windows cannot be seen. The round tower near this house looks old, but not so early as the house; the doorway and window-frames are of cut stone; the doorway-frame has a broad flat projection, and what appear to have been two heads standing out from the face of it. The stone here is not so hard as in other places, and is a good deal weather-worn; the masonry of the tower is rubble.

The next building of importance in the order of time is the Chapel of Cormac MacCarthy, King of Munster, on the Hock of Cashel, which has been clearly shown by Dr. Petrie in his learned and valuable work on the Hound Towers of Ireland, pp. 285, 286, to have been consecrated A.D. 1134, with great pomp, as recorded in the Irish annals. Dr. Petrie has quoted passages from, and given references to, several distinct authorities, all bearing testimony to the same point. This chapel is a small oblong building, with a chancel not quite so wide as the nave; it is vaulted, and ornamented in the richest style of Norman sculpture both within and without; it is said, probably with reason, to be the most richly ornamented building of its kind in Ireland. On each side, and at the junction of the nave and chancel, is a tall square tower, and at a short distance from it a round belfry-tower about the same height as the square towers, and apparently part of the same work. The whole is built of a soft sandstone, brought from a place about seven miles distant, and all of squared stones. The round tower is precisely of the same material and apparently the same work as the rest, excepting that it has two or three layers of the hard stone of the country, as if the supply of soft stone had run short.

In the roof of the chapel above the vault are small cells, or chambers, with a fireplace and other conveniences for habitation. These apartments are not on the same level; the one over the nave is about six feet higher than the one over the chancel, with a doorway and steps from one to the other; each apartment is lighted by two small windows, square-headed and widely splayed; the fireplace is at the west end, with a chimney in the thickness of the wall, and hot-air lines from it extending along the side-walls nearly level with the floor. This arrangement is believed to be perfectly unique at that period, and shows more attention to comfort than was then usual. The outer roof is formed of sandstone, but lined with tufa for the sake both of lightness and dryness. There are the corbels of a wooden floor, showing that there was an upper chamber, which was lighted by a small square window in the east gable. The carving of the capitals, mouldings, ribs, bases, and doorways, and the sculptures in the tympanum, are equal to anything in England or Normandy of the same period. Similar sculptured capitals and bases occur in the Church of the Nuns in the valley of Glendalough, also of soft stone, brought from some distance. The tomb of the founder, which has been removed from the arched recess on the outside of the chapel near the rich north doorway, is ornamented with the interlaced work popularly called Runic, but which has, I think, been clearly shown to be an Irish fashion originating in the imitation of wicker-work. Similar work and the same style of carving occur on the crosses at Kells.

The cathedral and castle of Cashel, which join to and partly inclose Cormac's chapel, are chiefly of the thirteenth century; the lower part of the castle, which forms the west end of the cathedral, and the lower part of the south transept, are of the end of the twelfth. In the roof of the cathedral over the vault is a series of chambers connected with the castle, and, in fact, forming part of it. The tower and parapets of the cathedral are all fortified, just in the same manner as the castle itself. In these apartments are some fine fireplaces; one in particular is a beautiful piece of construction of the kind called joggling, with a singular side-corbel to resist the thrust of the flat arch ; there are also several garderobes, and other usual marks of habitation.

The next building of this class is known by the name of St. Doulough's Church, and is situated about four miles north of Dublin. It is a very curious mixture of the castle, dwelling-house, and chapel or church, which last, in fact, forms a comparatively small part of the building. The date is probably the latter part of the thirteenth century, or the beginning of the fourteenth. In plan it is oblong, with a large square central tower, which has regular battlements of the usual Irish type in corbie-steps, evidently intended for use and not for ornament; the windows are small loops square-topped, just the same as those of the ordinary tower-houses. The chapel forms the eastern limb of the ground floor of the building; it has an east window of two lights, with mouldings of the fourteenth century; on the north side are single lancet-windows, on the south they are of two lights of the same style as the east window. It has a stone vault with habitable chambers above it in the roof, which is of ashlar masonry, and is remarkably high-pitched, reaching nearly to the top of the tower. There are other dwelling-rooms in the western division and in the tower; at the west end there are six small windows, one over the other, indicating that this portion of the building was divided into that number of small low rooms. The doorway is in a sort of shallow porch under a stair-turret projecting from the north-west corner of the tower, but extending only up to the second story; in this turret are several small windows, of single lights, trefoil-headed. The staircase is connected with the tower by a passage corbelled out in a singular manner, and has loopholes in the upper part; there are fireplaces and other marks of habitation in the chambers. The whole dimensions of this very singular building are only forty feet long by sixteen wide, external measure. It is remarkably lofty in proportion to its size. Near the church is the well-room, a curious small octagonal building with a dome-shaped vault, from which project four pointed dormers with stone roofs, and each with a small lancet-window, the head triangular, and under each window is a large cruciform loophole, excepting on one side, where there is a door. The whole structure appears to be of the thirteenth century. Adjoining to this is a small oblong chamber or bath-room called "St. Catharine's Pond," which has a pointed barrel-vault and a doorway, evidently of the thirteenth century also.

All the abbeys were fortified, and it was a general custom to have dwelling-rooms in the roofs of the churches above the vaults, but they hardly come within the description of domestic buildings, otherwise many of them might be described as partaking of that character. Bective Abbey is strongly fortified, and the original part is of the twelfth century. Holy Cross Abbey, near Thurles, co. Tipperary, has the ruins of a nave of the twelfth, but the greater part, including the beautiful chancel and transept, with the chambers over them, are of the fourteenth. Ross Abbey, near Headfort, co. Galway, has the cloister perfect; and a great part of the domestic buildings, with the kitchen and offices of the fifteenth century, may be made out, though in a ruinous state. The Abbot's house has suffered less. It is a small house of three stories, joining to the north-east corner of the chancel; it has fireplaces in the upper rooms, and an oven in the lower one: it is of the sixteenth century, rather later than the rest of the buildings, which are of the fifteenth. In the kitchen is a curious round reservoir of stone for keeping fish alive, with a stone pipe leading into it from the river. The chapter-house is tolerably perfect, and has in one corner a curious sort of bay window, popularly called a confessional, and having more of that appearance than usual. Here, as in most of the abbey churches in Ireland, a tall square tower of small dimensions has been built in the fifteenth century between the nave and chancel. Such towers are generally introduced within the walls of an earlier building, and the fashion spread so rapidly and so widely, that they were probably considered a necessary part of an improved mode of fortification. They usually have habitable rooms in them. Towers of this description remain at Hoare Abbey, near Cashel, and Kilmallock Abbey, co. Tipperary, Clare-Galway Abbey, co. Galway, Trim Abbey, and Swords, co. Meath, and many others. These square towers appear to have taken the place of the round towers as belfries for the churches, when the art of cutting stone had become more common. They are equally tall, and often nearly as slender, the size of the tower being remarkably small in proportion to the height. A few of them are probably of the fourteenth century, as at Drogheda, but the greater part are of the fifteenth. On the other hand the round towers are rarely later than the thirteenth, though some have had the upper story added or rebuilt in the fifteenth.

We come now to the Castles and Towers, which were the only dwelling-houses of the nobility and gentry of Ireland until the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Before that time it was not safe to live in a house that was not strongly fortified. The larger castles, such as Maynooth and Trim, on the borders of the English pale, were more properly military fortresses than domestic habitations; still they were the chief residences of great families. Maynooth, for instance, was the seat of the family of Fitzgerald, afterwards the Earls of Kildare, and originally built, or rather commenced, in 1176, by Maurice Fitzgerald, who had obtained a grant of the manor from Strongbow in that year; it was afterwards enlarged at various times, and was always a large and important castle. The additions have almost entirely disappeared; but the original Norman work, from its massive character, was not easily destroyed, and a great part of it still remains; the walls of the keep are perfect, and are eight feet thick; the ground floor is divided by a wall into two large vaulted chambers, with the entrances at one corner. The first floor is also divided into two large rooms, which have been the chief apartments, and are very fine lofty rooms, with others smaller and lower over them, and small chambers in the side-walls, eight feet six inches long, by four feet ten inches wide. The principal entrance was on the first floor from outworks now destroyed. There are also a gatehouse of the twelfth century tolerably perfect, and a large corner tower of the thirteenth; these have been connected by a range of buildings now destroyed. At the back of the corner tower are remains of another range of buildings, with three large round arches of wide span, which probably carried the vaults of this wing of the castle; but, being now left standing alone, they have a singular effect. Another oblong tower of the fifteenth century, now used as a belfry to the chapel, was also part of the castle, and serves to show its great extent. The doorway to the corner tower of the thirteenth century is built after the usual Irish fashion, wider at the bottom than at the top, with sloping sides, and a flat lintel. Much credit is due to the Duke of Leinster for the care which is now taken of these ruins.

That even this great castle, one of the largest and strongest in Ireland, was not merely a military fortress, but also the usual habitation of a great family, there is abundant evidence, into which it is not necessary to cuter in detail; a reference to the amusing account of the siege in the time of Henry VIII., given by Holinshed in his Chronicle, will suffice.[5]

Trim Castle is chiefly of the twelfth century, and the keep is on a very singular plan, which may be called cruciform There is a square central tower of considerable size, measuring sixty-four feet on each side and sixty feet in height, with a smaller square tower attached to the centre of each side, and a turret on each angle of the main building, sixteen feet high above the top of it. This large building is divided into two parts by a wall down the middle of it; there have been vaults over each story of the main building, but in the side towers only over the ground-floor room and near the top, with three stories between these two vaults, and one low story above the upper vault. The chief apartment or hall was on the first floor, and the kitchen by the side of it, on the same level; the fireplace remains, and several recesses in the walls for cupboards. The walls are not less than thirteen feet thick; there are not so many passages in them as usual, but several garderobes; the windows are small and square-headed. There is a large bailey, inclosed by a curtain wall, with ten round towers in the enceinte, all low and uniform; one larger than the rest is the gatehouse, and has the barbican nearly perfect. This gatehouse is later work than the rest, probably of the thirteenth century; the windows are larger; it has a fireplace and a garderobe on each floor. There is also a smaller back gatehouse less perfect This castle was built by Walter de Lacy in the time of Henry II. It is said, in the Chronicles of Ireland, to have been destroyed by Roderick O'Connor, King of Connaught, in 1220, and rebuilt the same year; but this could only mean that it was taken and dismantled, and was restored to a state of defence, probably stronger than before, by the addition of the new gatehouse. Such a mass of building once erected could not easily be destroyed, and certainly could not be rebuilt in a year. The same remark will apply to many other Norman castles and churches. The chroniclers always magnified the doings of their own days, and often described a building as "re-edified," which, on examination, we find to have been only repaired and restored to use.

The small decayed town of Dalkey was the chief harbour of Dublin throughout the middle ages, and down to a comparatively late period, until superseded by its more flourishing neighbour, now called Kingstown. It contains two of the small square castles, or tower-houses, and the ruins of a small church, of the twelfth century, and at a short distance from it is a more important house or castle, called Bullock Castle. The two towers appear to be of the twelfth century, but may possibly be later; they are very plain, with small windows, some round-headed, others square. The parapet of one is plain and solid, with a row of holes under it to let off the water, a general fashion in Ireland, sometimes with watershoots and sometimes not. This tower has a square stair-turret corbelled out at the south-west corner, a half octagon garderobe turret, also corbelled out, on the north side, and a chimney and a small bartizan projecting from the parapet. Is still inhabited; the ground floor is vaulted, above which are two stories with wooden floors. The second tower is very similar to the first, but later; it has a bartizan and a battlement in corbie-steps, the usual Irish battlement down to the sixteenth century, but not so early as the twelfth, when there was generally a plain solid parapet. Within it has a barrel-vault, and the putlog holes for a floor; the staircase is carried up obliquely in the thickness of the wall, but leads up above the vault into an octagonal turret; there are a fireplace and a garderobe to the dwelling-chamber.

Bullock Castle is a house of the twelfth century fortified in the usual manner. The plan is a simple oblong divided by a cross wall into two unequal portions, the lower story vaulted throughout. Above, in the larger division, are two principal rooms, one over the other; the windows small, round-headed, and widely splayed; some of the doorways are round-headed, others pointed; there is a fireplace in each of these rooms, and a garderobe in a turret at one corner, a small closet in another, with the staircase between. The smaller division of the house is divided into three stories above the vault, probably for bed-rooms, without fireplaces; the windows are square-headed, but splayed like the others. The ground-floor rooms under the vault were probably store-rooms; an archway passes through under one part of the house, as if for a communication from one courtyard to the other. At the top the two ends of the building are higher than the centre, forming a sort of towers, but all part of one design and built together, and there are battlements of the usual Irish form in steps. This plan of having the two ends higher than the centre is common in the Irish towers. The work is all plain and rude. There are remains of the outer wall inclosing a large bawn or bailey (ballium), and one of the corner towers remains. It is difficult to judge of the age of this sort of plain rude rough work: in England it would be twelfth-century without a doubt, but in Ireland it may be often much later: there are, however, generally, some indications of later work; and, where the windows and doors are round-headed, and there is little cut stone, it is probably of the twelfth century.

Loughmore Castle, co. Tipperary, consists of two parts. The greater portion is an Elizabethan mansion of the Purcells, but this has been added to an early keep of the beginning of the thirteenth century. The plan is oblong; the ground-floor is vaulted with a plain brick vault, and there is another vault near the top of the tower under the chief apartment, with wooden floors under it; there were altogether five stories; the windows are round-headed, but the doorways are pointed. The principal chamber at the top was a fine room, 36 feet 6 inches by 28 feet 6 inches internal measure, and lofty in proportion. The corbels of the timber roof and the weather moulding remain: over the roof there was a parapet on each side, and a covered passage or guard chamber at each end, with watchtowers at the corners. This tower is very substantially and well built of cut stone.

The Castle of Cashel is a large square tower forming the west end of the cathedral, and was begun in the twelfth century; the ground-floor and buttresses are of that period, but the greater part was built in the thirteenth, and the upper story partly rebuilt in the fifteenth. The internal arrangements are the same as in the other tower houses, with the usual vaults; there is a fine doorway of the thirteenth century from the cathedral into it. The outer doorway affords a good example of one of the modes of defending an Irish house. The door opens as usual into a small square space, forming a sort of inner porch, with three doorways besides the entrance; one straight forward into the lower vaulted chamber, one on the right hand to a small guard chamber or porter's lodge, the other on the left to the staircase: all the doors were securely barred, and to the outer door in the later castles there was a portcullis. This inner porch is usually about eight feet high, and is covered by a stone vault, in which is a small square opening called the "murthering hole," that usually opens into a small guard-chamber, in which a pile of stones would be kept ready in case of need. But at Cashel this mode of defence is carried one step further; the "murthering hole" opens into a small flue which goes straight up into the principal fireplace, close to the side of the fire, very convenient for pouring down boiling water, hot sand, or molten lead. The other doorway has a "murthering hole" with a similar flue brought up also near to the fireplace. The chief apartment was on the first floor over the vault, but had other rooms above it. There is a curious secret passage in the wall leading from the chief apartment to the rooms over the vaults of the cathedral; the entrance to it is not more than two feet square, just above the staircase; as soon as the opening is passed the passage is of the usual height.

Ballincolig Castle, near Cork, appears to be of the thirteenth century. It consists of a very tall square tower on the summit of a rock, with considerable remains of the wall of enceinte, which has bastions and other buildings attached to it, inclosing the bailey. The ground room is vaulted and had no entrance, excepting by a trap door from above, so that it was probably the prison. The room on the first floor is also vaulted; the space within the walls is only ten feet by eight; the entrance was into this room with a sloping road up to it, carried on arches. The windows are all small single lights, mostly with pointed heads, some square-headed; one has a trefoil .head with various rude incised ornaments on the surface over it, apparently a stone taken from some ancient building and used again. The second story is also vaulted, and has seats in the jambs of the windows, a drain from a lavatory, and a small square cupboard in the wall over it. The upper room or chief chamber has windows on all the four sides, with a stone socket for the iron rod of the casement to work upon. There is no fireplace in the whole tower, which was probably more of a keep for the last defence than a usual habitation; it has no bartizans or projections of any kind. The bastion towers in the wall of enceinte seem to be of the fifteenth century; the wall itself is very thick, and has loop-holes; on one side there are windows of two lights, as if of a hall, and there are a fireplace and chimney; this is part of the work of the fifteenth century, and seems to show that the buildings in the courtyard were inhabited at that time.

ORNAMENTAL BAND ON WINDOW SHAFT, ATHENRY CASTLE. |

BASE OF WINDOW SHAFT, ATHENRY CASTLE. |

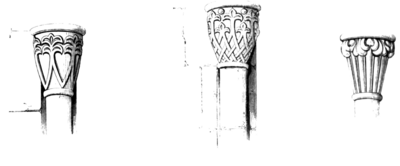

Athenry Castle, co. Galway, is a fine example of a fortified house or tower of the thirteenth century (see Plate VI.) ; the plan is oblong, and the ground-floor is divided into two parts by a row of arches down the middle, with two vaults, plain and massive. The chief apartment is on the first floor, upon those vaults, and had another vault over it; there are windows on three sides, and a fireplace (now broken away) at one end; the doorway is at one corner, leading to a bridge and barbican; the windows are of very good work of the thirteenth century, with moulded arches, banded shafts, and capitals having foliage of the Irish character (see woodcuts), though still distinctly in the style of the thirteenth century; they have seats in the jambs. The room above this was plain, and has no windows, but it has a passage in the thickness of the wall, with narrow slits for loopholes, as if it had been for defence only. The walls of the inner bailey remain, with two entrances, but in a ruinous state; the walls of the town appear to have served for a sort of outer bailey.

Borris Castle, near Thurles, co. Tipperary, is probably of the fourteenth century. It is quite plain and massive. There is only one vault, which is high up, having had throe stories with wooden floors under it; the doorways are all pointed; the windows mere loops, square-headed, splayed within, and having a wide chamfer on the exterior. Above the vault is the chief apartment, which has windows of two lights with ogee heads; they are long and narrow, and have rebates for the casements and holes for the bolts. One window only is cusped, and has a sort of perpendicular paneling on the outside; this is clearly of the fifteenth century, but seems rather later than the rest. This apartment is 27 feet long and 18 wide, and was lofty in proportion, with a timber roof, which had battlements on each side, passages at each end across the gable, and a watch-tower or bartizan at each corner, corbelled out on the tongue-shaped corbels which form one of the usual Irish fashions; the interstices between the corbels are machicoulis; these bartizans are half rounds clasping the angle of the tower, another Irish fashion. The staircase to the watch-tower is very ingeniously contrived for making the most of a small space; it is straight, and being only two feet vide, and also limited in space lengthwise, the steps, which are made triangular, like those of a winding staircase, are ten inches high, and placed with the broad end alternately right and left; by this means the ascent is double the usual height in the same space, without inconvenience. The lower part of the walls of the tower batters considerably, which is another feature of common occurrence in these Irish towers. The external measurement of this castle at the base is 43 feet by 38.

The remains of Dowth Castle, co. Meath, seem to be of the fourteenth century; but very little exists, and that little is modernised.

Gralla Castle, near Thurles, co. Tipperary, is a square tower of the fifteenth century, smaller and rather later than Borris Castle, but very similar to it in general appearance and arrangement. The entrance is into a small inner porch, with three doors, and the "murthering-hole" above, as before described. The ground-floor room is vaulted, and has no fireplace; there is a second vault above, with an intermediate floor. The chief apartment was at the top over the upper vault; it has windows of two lights of the fifteenth century, one cusped, the others with ogee heads. There are not the usual small rooms at the end of the hall on the same level, but above, at half the height of the hall, is a small chamber, probably a bed-room, with a fireplace in it; the mantelpiece of which is carried on corbels of the Irish tongue-shaped pattern. At the south end of the hall are three deep arched recesses, carrying the small chamber above. The ball or chief apartment measures 26 feet 6 inches by 21 feet 6 inches. On the east and west sides are several chimneys; one has lost the top, another has a conical head, with square openings all round under the coping for the smoke to escape. There is a curious arrangement for a garderobe in the thickness of the wall at the south end of the hall below the level, with a staircase, or rather a flight of steps, descending into it ; there is also a garderobe and a fireplace on each of the middle floors. The walls are very thick, and batter considerably; the loopholes to the room on the ground-floor are rudely splayed on the outside.

Mycarkey Castle, near Thurles, is another square tower-house of the fifteenth century, very similar to those already described, but with the wall of enceinte remaining, and rather different in internal arrangement from the others The vault is near the middle of the elevation of the tower, with two floors under it, and two over it; the interior is also divided by a wall, parting off small bed-rooms without fireplaces; the larger rooms have fireplaces. The chief apartment, as usual, was at the top; but the one under it, on the vault, was of nearly equal importance, measuring twenty-two feet by seventeen. The wall of enceinte has an alure behind a parapet, with cruciform loopholes; at one corner of it is a round tower of two stories, with embrasures for falconets, or small cannon. The internal measurements of the bailey are 166 feet by 148.

Ballynahow Castle, near Thurles, is a round tower-house; in other respects much like the square towers in the same neighbourhood. The entrance is into a small inner porch, as usual; the ground room vaulted. On the first floor is a large fireplace, apparently for a kitchen; it has a flat joggled arch, and is ornamented with a sort of cable moulding. The rooms are square within, and the space between the flat wall and the round outer wall is used in different ways; on one side is a sort of cellar or pantry; on another a garderobe, with a cruciform loophole; a third side is occupied by the fireplace; the fourth appears to be solid; the windows are at three of the corners of the room; in the fourth is the doorway to the staircase; there are embrasures for falconets on this floor and below. Over the kitchen was another room with a wooden floor, and over that another vault, above which was the principal chamber, which is octagonal within, and has three windows of two lights with ogee heads; and in the recesses are embrasures on each side of the windows; a large square fireplace, chimney, and a garderobe. There are a parapet and alure round the top, and bartizans are thrown out on corbels, exactly like those at Borris Castle.

At Thurles there are three of the tower-houses of the fifteenth century: one near the bridge seems to have been a gatehouse, as the springing of an arch over the road remains against the side of the tower; it contains a vault, with floors above and below it, fireplaces, and garderobes on each floor, so that it was evidently intended for habitation. Another tower near the market-place is late in the fifteenth century, but rather a good example; it has two vaults—one over the ground floor, the other over the third floor, and over this the chief apartment, making five stories in all, with a fireplace in each, and a garderobe at the end of a passage in the wall, on each floor. In the upper chamber are five deep recesses, four of which have windows in them; the fifth seems to have been a lavatory, as there is a water-drain from it. The battlements are destroyed. Near this are the ruins of a round tower-house, and within a few years there were two other square towers near these; and the whole were connected by a wall of enceinte, inclosing a bailey of considerable size; of this wall there are some remains; probably the other towers were bastions in the outer wall. It must have been a castle of some importance.

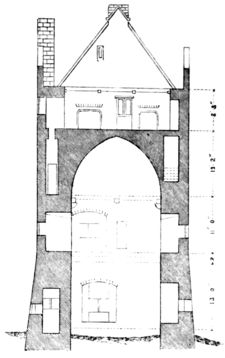

Annadown Castle, co. Galway, appears to belong to the fifteenth century; it is situated on the shore of a little bay of Lough Corrib; the bay is about a bowshot across, and immediately opposite, close to the shore, are the ruins of the abbey and of the parish church of Annadown. The arrangements of this castle are shown by the accompanying ground-plan and section. The existence of a castle at this spot seems to have sprung from the desire of the Archbishops of Tuam to suppress the bishopric of Annadown, which was several times extinguished and revived; and in 1252, Florence, Archbishop of Tuam, obtained from Henry III. a confirmation of a papal bull for the suppression of the see, on condition that a castle should be built on the church lands; the bishopric, however, continued, with short intervals, to exist; but in 1421 the last bishop who held the see was appointed, and it is to him that the erection of the present castle is probably due.[6]Kilmallock is an interesting town to the antiquary, being full of ruins of old buildings, but the most important of these are ecclesiastical, and some others belong to the Elizabethan period. There are two gatehouses of the fifteenth century, but in a bad state, and not very remarkable; one of them is inhabited. In the principal street is a row of Elizabethan town houses of good character, worthy of the attention of architects for modern street-houses.

Fanstown Castle, near Kilmallock, is another tower-house of the fifteenth or early part of the sixteenth century, with two vaults and three stories over the upper one, six in all; with a fireplace and garderobe on each floor, and two fireplaces in the upper chamber. There are bartizans at two corners of the chief apartment over the vault, but not at the top of the tower; these are furnished with loopholes, and small round holes for muskets.

Ballygruffan Castle, near Bruff, consists of the ruins of a large fortified tower of the sixteenth century, with a square tower in the centre, which is more perfect than the rest. There are bartizans both to the tower and to the outer walls; with corbels in imitation of the earlier examples, and single-light windows, with sloping sides and trefoil-heads, but all evidently imitation work of the sixteenth century.

Bruff Castle is a mere ruin of a house of the fifteenth century, but the vaulted lower story remains, and in the wall of it is a doorway with sloping sides and a flat lintel, exactly like those in the round towers.

Blarney Castle, near Cork, consists of the ruins of two mansions, one a tower-house of the fifteenth century, the other Elizabethan added to the former. The walls of the earlier house are nearly perfect, with the battlements carried on corbels of the usual tongue-shape, the intervals between forming large machicoulis; the alure remains on the top of the wall behind them, and is covered with thin slabs formed into gutters. At one corner is a watch-turret, on the parapet of which is the celebrated "Blarney stone." At another corner, opposite the watch-turret, is a larger turret rising from the ground, at the top of which is the kitchen with the large fireplace and chimney; this turret has a separate battlement and machicoulis at a lower level than the great tower. In this turret there are two rooms under the kitchen, and a separate staircase for servants, and from the room under the kitchen there is a flight of steps leading to the principal apartment in the great tower. In this principal tower the vault is over the second story, and there has been another vault two stories higher, and a fifth story over the upper vault; in this room is a single-light window or loop, with sloping sides after the old fashion. The enceinte has a round tower belonging to the Elizabethan work of the sixteenth century. (See Plate VI.)

Carrigrohan Castle, near Cork, is an oblong tower-house of the sixteenth century much modernised, with bartizans at two of the corners, in which are small round holes for musketry, but carried on machicoulis. The face of the wall projects, and overhangs about six inches in each of the upper stories, perhaps for the purpose of throwing off the wet more effectually. There are remains of outworks and a curtain wall.

Dundrum Castle, in Blackrock, near Cork, is the ruin of a square tower-house of rich and massive work, so much covered with ivy that it is difficult to make out what it has been. It is three stories high, with fireplaces in the two upper ones and a staircase in the wall obliquely. There is a servants' room or turret joined to one side. The doorway and windows are square-headed. It is most probably of the fifteenth century.

Ballinagheah (or the Castle of Sheepstown), near Athenry, co. Galway, a tower-house of the fifteenth century, with alterations of the sixteenth. The vault is high up, over the third story, and there were two stories over it; a fireplace and garderobe in each story; one end of the tower is parted off by a wall, forming a sort of separate turret, divided by floors into bedrooms. The original windows are single lights, trefoil-headed, with interlaced ornaments in the spandrels; square windows are introduced in the upper stories. A bartizan at each of the four corners is corbelled out on the usual tongue-shaped corbels; there are two chimneys, one on each side. The alure is perfect, but the parapet nearly all gone. The staircase is good, of well-cut stone, with the angles rounded for a newel; in most of the Irish stair-turrets the angles at the end of the steps are left sharp, instead of the round newel usual in England. The lower part of the walls batters considerably. The principal doorway has sloping sides and a pointed arch. The hard limestone is here well worked. None of the building is earlier than the fifteenth century.Aughnanure Castle, co. Galway, on the borders of Connemara, is a fine castle of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The central keep is nearly perfect; the outworks are in ruins; the work is very good, and there is ornamental carving in parts of it; one end has been rebuilt or altered in the sixteenth century; the earlier part is the best work. The state-room is at the top upon the vault, as usual, with windows of two lights trefoil-headed, splayed to a wide round-headed arch within; they have long and narrow lights divided by a transom, the lower part built up, and openings left for culverins. One square window is inserted; there is a large fireplace in the upper room. The garderobes are arranged in a turret within the walls; that is, they are placed one over the other, with a pit at the bottom open to the moat. There is a vaulted prison or dungeon with one small window and a square hole in the vault over it for a trapdoor, and no other entrance to it. One end of the tower is parted off and divided into small bedrooms. There are three stories under the upper vault: the entrance is into an inner porch of the usual Irish character. Two bartizans project from the first floor at the angles next the entrance, and there are portions of others from the battlements above, and the corbels remain in the centre of each face of the tower. Parts of the walls and turrets to both the outer and inner baileys exist, with a round tower in which are two domed vaults of the beehive construction, but evidently part of the work of the time of Henry VIII. A fine banqueting hall was built in the outer bailey at that period, one end wall of which only remains with the windows in it; they are tall and square-headed, with transoms and ogee heads to the lights, with dripstones over; the spandrels and the under sides of the dripstones enriched with carvings of late character and shallow work, which may perhaps be Elizabethan. This castle is built over a cavern in the limestone rock; a small river runs under it, and partly round it, forming the moat.

Ballinduff Castle, co. Galway, is a plain square tower of the fifteenth century, very well built of cut stone, three stories high, the walls very thick, with two vaults. The ground-floor room seems to have been a dungeon, and the staircase which now leads from the trap-door is a later insertion. On the first floor the windows are very small, with large recesses within. The upper room has also small narrow lancet windows, one with an ogee head, another with the shouldered lintel; no fireplace or locker in the wall. The staircase from the first floor to the top is in the thickness of the wall, and very well built. The battlement is destroyed, but the alure remains, with the corbels of a bartizan projecting from it. On the first floor is a garderobe, quite perfect, with the passage to it round a corner. There is no original fireplace in any part of the building, which seems to have been a keep only; but there are ruins of a small low building attached to the east end, with a doorway into it, which is said to have been the kitchen of the castle, and this appears probable.

Clare-Galway Castle is another fine square tower-house of the end of the fifteenth century. The entrance doorway is large, and was protected by a portcullis, of which the groove only remains; it opens into one of the usual inner porches with three doorways and the "murthering hole" in the vault above; and over this is a small vaulted chamber for the windlass to the portcullis, and to contain a pile of stones for throwing down in case of need on the heads of assailants through the murthering hole. The ground-floor room has three windows, but no fireplace; the large room on the first floor has a fireplace, and a boarded floor, with passages in the thickness of the walls, in which are loopholes; one leads to a garderobe. Over this is another low room under the vault; another small vaulted chamber on this floor has a fireplace and a garderobe, and appears to have been a bed-room. The principal chamber is above the vault, and measures 31 feet by 21, and was 18 feet high to the springing of the roof. Some of the windows are of two lights with ogee heads; others are single-lights pointed; the walls are 5 feet 6 inches thick at the top, but the windows have large embrasures, and there are three closets and two arches in the walls. The garderobe is approached by a staircase and passage in the wall on the way up to the battlements, which are destroyed.

Corr Castle, on the Hill of Howth, near Dublin, is a small tower-house of the fifteenth century, with a stair-turret projecting on one side. The windows are very small, and mostly square-headed; one has an ogee head and perpendicular tracery. The parapet is plain, not in battlements, but with a stone alure behind it, and the usual openings through to let off the water; it had a low building attached to it, probably a kitchen.

Drimnagh Castle, near Dublin, is a plain mediæval house still inhabited, and so deprived of all its original character that it is very difficult to assign a date to it, but is probably of the fifteenth century. All the windows and dressings are modern, but it is built of rough stone, hammer-dressed only, and the walls are thick. The moat is perfect, and washes the foot of the wall on one side. The plan is oblong, with a square tower at one end, under which is the entrance gateway, with a plain barrel-vault and a round arch. On the outer side of the tower is a stair-turret carried up above the roof, and a watch-turret with external stairs to it. The battlement is in steps, with a good coping and the alure behind it, and has the usual openings for carrying off the water.

Swords Castle, near Dublin, has been a large and important castle, but little now remains except the outer wall of enceinte, which is tolerably perfect, with its battlements and alure, a square tower at the north-east corner, an entrance gateway in the centre of the south side, remains of a large hall or chapel on the east side of it, and ruins of other buildings on the west. The large room which looks like a hall has only bare walls in a dilapidated state, and remains of the canopy of a niche at the cast end, which seems to agree with the popular notion that it was a church. The whole of these ruins appear to be of the fifteenth century, though some of the windows have trefoil heads.

Malahide Castle is interesting from its history; it was founded by Richard Talbot in the reign of Henry II., has always been inhabited by the same family, and is still occupied by his lineal descendant, the present Lord Talbot de Malahide. Unfortunately the improvements which have been made from time to time, according to the tastes of successive lords, have left very little of ancient character in any part of the building. The stone vaults of the cellars and offices, and part of a stone staircase, are probably of the fifteenth century, but there is nothing that appears to be earlier. The hall and the oak chamber are of the time of James I. There are several towers, round and square, with battlements, but plastered over on the outside, and thoroughly modernised within. The castle is beautifully situated, and the effect at a distance is extremely picturesque, but it does not repay the examination of the antiquary.

Howth Castle, near Dublin, is an extensive range of building, still inhabited by Lord Howth, and much modernized. The original parts are probably of the beginning of the sixteenth century. The entrance gatehouse remains, with a round arch and a barrel-vault; other buildings occupy three sides of a courtyard, with towers at the corners; the fourth tower has been rebuilt, and most of the curtain wall is now occupied by modern buildings. Part of the wall of enceinte remains, and incloses a large outer bailey; and one of the round towers at the corner is of large dimensions, and pierced with embrasures for cannon.

Strongford Castle, near Athenry, co. Galway, is a small house or fortress of only two stories, with a vault between. The walls are thick, the rooms small, and the work very rude and rough, but the arrangement does not appear to be early; and whatever architectural character there is belongs to the sixteenth century; but it may possibly have been originally of the fifteenth, much altered in the sixteenth. The entrance is protected by the usual inner porch, and had a portcullis, of which the groove remains. There is a large fireplace in the room on the first floor, and a garderobe from the staircase; the doorway of this room looks early, and has the shouldered lintel; there is a cruciform loophole on this floor. The windows are chiefly small square-topped loops. There are bartizans projecting from two of the angles, of rubble-work on plain corbels, with small round and square holes for musketry and culverins.

The town of Galway has many houses of the Elizabethan period, but most of them have been newly fronted and modernised. One of the tower gatehouses remains near the river, but in a ruinous state, and so plain that it may be of any period from the twelfth century downwards; it is probably late. There are two low round arches, with remains of rooms over them, and a stair-turret by the side, which has a single-light window with a trefoil head, very similar to many others of the fifteenth century in the Irish castles.

The best house in the town is the one called Lynch Castle, which was the residence of the great family of that name, but has been entirely rebuilt within the last few years; fortunately the architect employed to commit this piece of barbarism had sufficient taste to preserve as much of the old carved stonework as possible, and built it in again as ornament in the face of the wall, but with little regard to its original position or use. This carved work is extremely beautiful, and admirably executed in the hard limestone of the country; but it is of the very latest Gothic character, and thoroughly Irish; the idea of its being of Spanish character is a mere fancy. Amongst the ornaments built in on the face of the wall are the royal arms of England, with the greyhound and dragon for supporters; these supporters were used occasionally by Henry VII., Henry VIII., and Elizabeth, but there seems reason to assign them in this instance to Henry VIII. The details of ornament in the carving are so identical with some of the work at the church, that there is no doubt both were executed at the same time, and probably by the same hands; but the church is a large one, and the work of rebuilding it was continued over a long period, so that it is difficult to fix an exact date. The dripstones are enriched with ornament; one of the windows built in has perpendicular tracery, and the old gurgoyles are placed up again. The following extract from the will of Dominick Lynch, 1508, shows that the work at the church was then going on, and this seems a probable date for that of the house also:—"Item. I order the said Stephen to finish the new work begun by me in the church."[7]

Another house, called Castle Banks, bears the date of 1612. It has a fine Jacobean fireplace with the family arms, and a good doorway round-headed, with a label over; the spandrels and corbels well carved; the corbels of the Irish tongue-shape, with foliage springing from the points.

Another house of Elizabethan character bears the date of 1627 over the gateway, with the names Martin Brown and Maria Lynch, and their respective coats of arms.

Several of the Elizabethan doorways in this town are ornamented with sculpture in stone, and the interlaced patterns, popularly called Runic, are used in them, showing that this kind of ornament was used in Ireland throughout the whole of the mediæval period. In some instances this interlaced work is found at the back of the head, on corbel heads terminating dripstones, and is continued for some distance along the wall as an ornament, as if it had been intended to represent the long hair of the Irish ladies plaited, for the women of the lower classes in this part of Ireland have very long and beautiful black hair, and pride themselves not a little upon it.

The peat-bogs, in which large oak trees have frequently been found, and various other indications, show that a large part of Ireland was formerly covered with oak forests. Irish oak formed an important article of trade during the middle ages; many roofs of churches and halls of this material are to be met with in various parts of England and the Continent; and frequent mention of Irish oak occurs in French chronicles; it was much prized, and was frequently employed in making boxes or coffers for relics or other purposes. The want of drainage and the neglect of keeping open the natural outlets seem to have been the causes of the destruction of these forests and the conversion of them into bogs.

The foregoing observations are the result of a fortnight's tour in Ireland in the summer of 1858. I should hardly have ventured to offer them to the notice of the Society of Antiquaries, had I not been encouraged to do so by several of the Fellows who thought them novel and interesting, and had I not felt that my previous acquaintance with mediæval architecture in general, and with the best works upon the subject of the architecture of Ireland in particular, often enabled me to see at a glance more than would be learned by long study without such previous information. The works to which I have been chiefly indebted are Dr. Petrie's learned and valuable work on "the Round Towers," and Mr. Wilkinson's sensible practical book on "the Geology and Architecture of Ireland." Mr. Wakeman's little guide-book I have also found very useful, and I have consulted several other works which it is not necessary to mention. Previous to setting out for Ireland, I was supplied, by the kindness of Lord Talbot de Malahide, with a list of the objects most likely to be useful for my purpose; I had also the pleasure of being personally acquainted with Dr. Petrie, Archdeacon Cotton, and Sir John Deane; and the direction of my tour was in some degree guided by these considerations. As soon as I arrived in Dublin I called on Dr. Petrie, who recommended me to take his former pupil Mr. Wakeman with me into Galway, by whose assistance I was enabled to make the most of my time. I then went for a few days on a visit to nay friend Archdeacon Cotton at Thurles, and he enabled me to see everything within reach of his house, including Holycross Abbey and the Rock of Cashel, and gave me all possible information respecting them. I then went on to Cork to see Sir John Deane, who gave me the same kind assistance for his neighbourhood. To all of them I return my cordial thanks; but I must not be understood to imply that any of these gentlemen are in the slightest degree responsible for my opinions, which may have been hastily formed, and require correction in some particulars; but I believe that my observations are new to the generality of English antiquaries.

I remain, my Lord,

Your very obedient Servant,

- ↑ For an account of bee-hive houses in the county of Kerry, see Mr. Dunoyer's memoir, Archæological Journal, vol. xv. p. 1.

- ↑ [The Society are indebted to Mr. Parker for the use of this woodcut]

- ↑ There appears strong reason to believe that the vault and stone roof are part of the alteration in the twelfth century, and the ledge may arise from the greater thickness of the earlier walls, which had originally the floors and roof of wood. The construction of the base of the round tower in the west gable shows that the vault and roof were built with it, and added upon the walls of Cyclopean masonry; all the upper part is of small stones. There is a space between the top of the vault and the ridge of the roof, but hardly sufficient to have been used for any purpose, and there was apparently no access to it.

- ↑ It seems probable that this arch and tympanum belong to the work of the twelfth century; the lower parts of the walls are Cyclopean, but this arch is of small stones.

- ↑ "Great and rich was the spoile, such store of beddes, so many goodly hangings, so rich a wardrob, such braue furniture, as truly it was accompted for housholde stuffe and vtensiles one of the richest earle his houses vnder the Crowne of Englande." The account of the siege, sent to the King by the Lord Deputy, Sir William Skeffington, confirms this. It appears that the garrison consisted of little more than 100 able men. "Ther was within the same above 100 habill men, wherof were above 60 gunners." Of this garrison, 60 were killed in the assault, and 37 taken prisoners; and 26 of them were executed two days afterwards, after being tried by a court martial.—State Papers of Henry VIII. vol. ii. p. 236.

- ↑ I am indebted to G. M. Hills, Esq. Architect, for the drawings and description of this castle, which I was prevented from visiting personally.

- ↑ Hardiman's History of Galway, p. 235.