A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Chant

CHANT. To chant is, generally, to sing; and, in a more limited sense, to sing certain words according to the style required by musical laws or ecclesiastical rule and custom; and what is thus performed is styled a Chant and Chanting, Cantus firmus, or Canto fermo. Practically, the word is now used for the short melodies sung to the psalms and canticles in the English Church. These are either 'single,' i.e. adapted to each single verse after the tradition of 16 centuries, or 'double,' i.e. adapted to a couple of verses, or even, according to a recent still greater innovation, 'quadruple,' ranging over four verses.

The qualifying terms Gregorian, Anglican, Gallican, Parisian, Cologne, etc., as applied to the chant, simply express the sources from which any particular chant has been derived.

It is historically incorrect to regard the structure of ancient and modern chants as antagonistic each to the other. The famous 'Book of Common Praier noted,' of John Marbeck (1559), which contains the first adaptation of music to the services of the Reformed Anglican Church, is an adaptation of the ancient music of the Latin ritual, according to its then well-known rules, mutatis mutandis to the new English translations of the Missal and Breviary. The ancient Gregorian chants for the psalms and canticles were in use not only immediately after the Reformation, but far on into the 17th century; and although the Great Rebellion silenced the ancient liturgical service, with its traditional chant, yet in the fifth year after the Restoration (1664) the well-known work of the Rev. James Clifford, Minor Canon of S. Paul's, gives as the 'Common Tunes' for chanting the English Psalter, etc., correct versions of each of the eight Gregorian Tones for the Psalms, with one ending to each of the first seven, and both the usual endings to the eighth, together with a form of the Peregrine Tone similar to that given by Marbeck[1]. Clifford gives also three tones set to well-known harmonies, which have kept their footing as chants to the present day. The first two are arrangements of the 1st Gregorian Tone, 4th ending—the chant in Tallis's 'Cathedral Service' for the Venite—with the melody however not in the treble but (according to ancient custom) in the tenor. It is called by Clifford 'Mr. Adrian Batten's Tune'; the harmony is essentially the same as that of Tallis, but the treble takes his alto part, and the alto his tenor. The second, called 'Christ Church Tune' and set for 1st and 2nd altos, tenor, and bass, is also the same; except the third chord from the end—

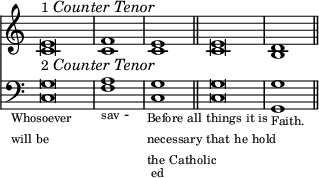

Christ Church Tune.

Clifford's third specimen is quoted as 'Canterbury Tune,' and is that set to the Quicunque vult (Athanasian Creed) in Tallis's 'Cathedral Service'; but, as before, with harmonies differently arranged.

Canterbury Tune.

It has all the characteristics of the 8th Gregorian Tone, with just such variations as might be expected to occur from the lapse of time, and decay of the study of the ancient forms and rules of Church music.

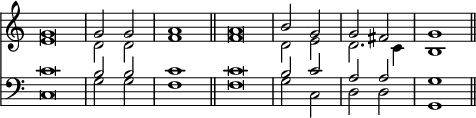

The fourth of Clifford's examples is also a very good instance of the identity, in all essential characteristics, of the modern Anglican chant and the ancient Gregorian psalm tones. It is an adaptation of the 8th Tone, 1st ending—the tone being in the Tenor:—

The Imperial Tune.

The work published in 1661 by Edward Lowe, entitled 'Short Directions for the Performance of Cathedral Service' (2nd ed., 1664), also gives the whole of the tones, and nearly all their endings, according to the Roman Antiphonarium, and as Lowe had sung them before the Rebellion when a chorister at Salisbury. He also gives the harmonies quoted above as the 'Imperial' and 'Canterbury' tunes, and another harmony of the 8th Tone, short ending (Marbeck's 'Venite') with the plainsong in the bass.

The 'Introduction to the Skill of Music,' by John Playford (born 1613 [App. p.584 "1623"]), in its directions for the 'Order of Performing the Divine Service in Cathedrals and Collegiate Chapels' confirms the above statements. Playford gives seven specimens of psalm tones, one for each day of the week, with 'Canterbury' and the 'Imperial' tunes in 'four parts, proper for Choirs to sing the Psalms, Te Deum, Benedictus, or Jubilate, to the organ.'

The Rev. Canon Jebb, in the second volume of his 'Collection of Choral Uses of the Churches of England and Ireland' (Preface, p. 10), gives from the three writers quoted and from Morley's 'Introduction' (1597) a table of such old English chants as are evidently based upon or identical with the Gregorian psalm tones.

It is interesting to note also that in the earliest days of the Reformation on the Continent, books of music for the service of the Reformed Church were published, containing much that was founded directly upon the Gregorian plainsong; and it was chiefly through the rage for turning everything into metre that the chant proper fell into disuse among Protestant communities on the Continent. See the 'Neu Leipziger Gesangbuch' of Vopelius (Leipzig 1682).

The special work for the guidance of the clergy of the Roman Church, and all members of canonical choirs, in the plainsong which they have specially to chant, is called the Directorium Chori. The present Directorium corresponds to the famous work prepared by Guidetti (1582), with the aid of his master Palestrina. But as is the case in most matters of widespread traditional usance, differences are found between the books of present and past liturgical music, not simply in different countries and centuries, but in different dioceses of the same country and the same century. The York, Hereford, Bangor, and Lincoln 'uses' are named in our Prayer Book, as is also that of Salisbury, which obtained a foremost place of honour for the excellence of its church chant. Our own chants for the responses after the Creed, in the matins and vespers of English cathedrals, are the same to the present day with those found in the most ancient Sarum Antiphonary, and differ slightly from the Roman.

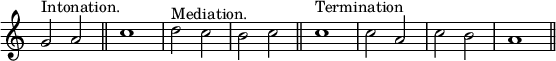

The psalm tone, or chant, in its original and complete form, consists of (1) An Intonation at the beginning, followed by a recitation on the dominant of its particular mode; (2) A Mediation, a tempo, closing with the middle of each verse; (3) Another recitation upon the dominant with a Termination completing the verse, as in the following—the Third Tone:—

In the modern Anglican chants the Intonation has been discarded, and the chant consists of the Mediation and Termination only.

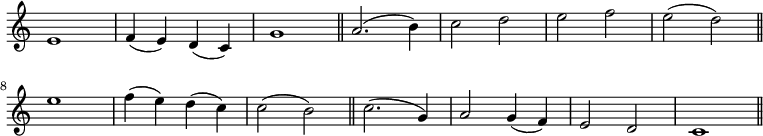

When the tune or phrase coincides with a single verse of the psalm or canticle it is styled a 'single chant,' as are all those hitherto cited. At the time of the Restoration, as already stated, the Gregorian chants were still commonly used, till lighter tastes in music and the lessened numbers of men in cathedral choirs led to the composition of new treble chants and a rage for variety. Some of these, which bear such names as Farrant, Blow, and Croft, are fine and appropriate compositions. But a different feeling gradually arose as to the essential character of church music; double chants, and pretty melodies with modern major or minor harmonies, came to be substituted for the single strains, the solemn and manly recitation tones, and the grand harmonies of the 16th century. The Georgian period teemed with flighty chants, single and double; many of which can hardly be called either reverential or beautiful—terms which no one can apply to the following (by Camidge [App. p.584 "Crotch"],) still in frequent use, and by no means the worst that might be quoted:—

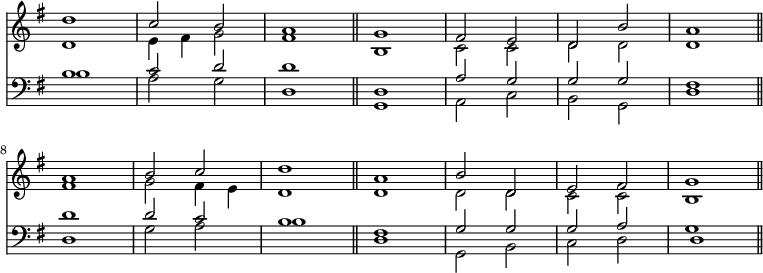

But however objectionable this practice may be regarded, it must be confessed that many very charming melodies have been produced on the lines of the modern double chant by modern composers of great eminence. The following by Dr. Crotch is remarkable for its grace and elegance, as well as for the severity of the contrapuntal rule to which the quondam Oxford professor has subjected himself in its construction (per recte et retro). Each of the four parts in the former half of the chant has its notes repeated backwards in the corresponding bars of the second half.

It remains to add a few remarks on the arrangement of the words in chanting.

That the principles of the old Latin chanting were adopted in setting the music to the new English liturgy and offices, is evident from every text-book of English chanting from Archbishop Cranmer's letter to Henry VIII and from Marbeck downwards, as long as any decent knowledge of the subject remained in English choirs. Little by little, however, the old rules were entirely neglected; generally speaking, neither the clergy nor the lay members of the English choirs knew anything more about chanting than the oral traditions of their own churches; thus things grew gradually worse and worse, till no rule or guide seemed left; choirmen and boys took their own course, and no consent nor unity of effect remained, so far as the recitation and division of the words were concerned.

On the revival of Church principles in 1830–1840 our own English documents of ecclesiastical chanting, and the pre-Reformation sources from which they were derived, began to be studied. Pickering and Rimbault each re-edited Marbeck. Dyce and Burns published an adaptation of his plainsong to the Prayer Book. Oakley and Redhead brought out the 'Laudes diurnæ' at the chapel in Margaret Street, London. Heathcote published the Oxford Psalter, 1845. Helmore's 'Psalter Noted' (1849–50) took up Marbeck's work, at the direction after the Venite—'and so with the Psalms as they be appointed'—and furnished an exact guide for chanting according to the editor's view of the requirements of the case. Moreton Shaw, Sargent, and J. B. Gray also published Gregorian Psalters.

Meantime the modern Anglican chant was being similarly cared for. Numerous books, beginning with that of Mr. Janes (1843), issued from the press, giving their editors' arrangement of the syllables and chant notes for the Psalter and Canticles. Among the most prominent of these may be mentioned Mr. Hullah's 'Psalms with Chants' (1844); Helmore's 'Psalter Noted' (1850); the Psalter of the S.P.C.K. edited by Turle (1865); the 'English Psalter' (1865); the 'Psalter Accented' (1872); the 'Cathedral Psalter' (1875); the Psalters of Ouseley, Elvey, Gauntlett, Mercer, Doran and Nottingham, Heywood and Sargent. Among these various publications there reigned an entire discrepancy as to the mode of distributing the words. Beyond the division of the verse into two parts given in the Psalms and Canticles of the Prayer Book, no pointing or arrangement of the words to the notes of the chant has ever been put forward by authority in the Anglican Church, or even widely accepted. Each of the editors mentioned has therefore followed his own judgment, and the methods employed vary from the strictest syllabic arrangement to the freest attempt to make the musical accent and expression agree with those which would be given in reading—which is certainly the point to aim at in all arrangements of words for chanting, as far as consistent with fitness and common sense. It may be hoped that the increased attention given to this important subject, may lead to the use of those guide books only which best reconcile the demands of good reading and good singing.- ↑ See Table of chants in 'Acc. harmonies to Brief Directory,' by Rev. T. Helmore. App. II. No. cxi.