A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Drum

DRUM. Some instrument of this kind has been known in almost every age and country, except perhaps in Europe, where it appears to have been introduced at a comparatively late period from the East.

A drum may be denned to be a skin or skins stretched on a frame or vessel of wood, metal, or earthenware, and may be of three different kinds:—

1. A single skin on a frame or vessel open at bottom, as the Tambourine, Egyptian Drum, etc.

2. A single skin on a closed vessel, as the Kettledrum.

3. Two skins, one at each end of a cylinder, as the Side-drum, etc.

1. The first sort is represented by the modern tambourine, and its varieties will be described under that head. [Tambourine.]

2. The second kind is represented by the modern Kettledrum the only really artistically musical instrument of this class. It consists of a metallic kettle or shell, more or less hemispherical, and a head of vellum which, being first wetted, is lapped over an iron ring fitting closely outside the kettle. Screws working on this ring serve to tighten or slacken the head, and thus to tune the instrument to any note within its compass. The shell is generally made of brass

In the key of F, the tonic and dominant may be obtained in two ways (d), and likewise in B♭ (e), but in all other keys in only one way.

Thus in F♯, G, A♭, and A, the dominant must be above the tonic,

while in B♮, C, C♯, D, E♭, and E, the dominant must be below the tonic,

Drums are generally tuned to tonic and dominant; but modern composers have found out that they may advantageously stand in a different relation to each other. Thus Beethoven, in his 8th and 9th Symphonies, has them occasionally in octaves (f), and Mendelssohn, in his Rondo Brillante, most ingeniously puts them in D and E (g); thereby making them available in the

keys of B minor and D major, as notes of the common chord, and of the dominant seventh, in both keys. By this contrivance the performer has not to change the key of his instruments all through the rondo—an operation requiring, as we shall see, considerable time. Berlioz says that it took seventy years to discover that it was possible to have three kettledrums in an orchestra. But Auber's overture to 'Masaniello' cannot be played properly with less, as it requires the notes G, D, and A; and there is not time to change the G drum into A. In Spohr's 'Historical Symphony' three drums are required all at once in the following passage:

And in 'Robert le Diable' (No. 17 of the score) Meyerbeer uses three drums, C, G, and D [App. p.618 "Meyerbeer uses four drums, G, C, D, and E"].

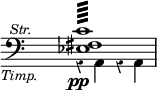

Another innovation is due to Beethoven, namely, striking both drums at once. This occurs in his 9th Symphony, where, in the slow movement, the kettledrums have![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \clef bass r8 << { f8[ f] f4 } \\ { bes,8[ bes,] bes,4 } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/d/qdnm86nlvwt6fgq0wmp12z29evsa8jm/qdnm86nl.png)

In the wonderful transition from the scherzo to the finale of the 5th Symphony, the soft pulsations of the drum give the only signs of life in the deep prevailing gloom. Of the drums in octaves in Beethoven's 8th and 9th Symphonies, we have already spoken. And in reviewing his Violin Concerto, which begins with four beats of the drum, literally solo, an English critic observes that 'until Beethoven's time the drum had, with rare exceptions, been used as a mere means of producing noise—of increasing the din of the fortes; but Beethoven, with that feeling of affection which he had for the humblest member of the orchestra, has here raised it to the rank of a solo instrument.'

The late Mr. Hogarth says that 'to play it well is no easy matter. A single stroke of the drum may determine the character of a whole movement; and the slightest embarrassment, hesitation, or misapprehension of the requisite degree of force, may ruin the design of the composer.'

There are many sorts of sticks. The best are of whalebone with a small wooden button at the end, covered with a thin piece of very fine sponge. With these every effect, loud or soft, can be produced. A small knob, not exceeding 1¼ inch in diameter, entirely made of felt on a flexible stick, answers very well. India-rubber discs are not so good. Worst of all are large clumsy knobs of cork, covered with leather, as they obscure the clear ring of the kettledrum, so different from the tone of a bass drum.

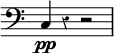

Very large drums, going below F, have not a good musical tone, but mere thunder. Thin transparent skins have a better tone than the opaque white ones. The right place to strike a kettle-drum is at about one-fourth of its diameter. A roll is written in either of the following ways,

and is performed by alternate single strokes of the sticks. We shall see presently that the side-drum roll is produced in quite a different manner.

Drum parts were formerly always written, like horn and trumpet parts, in the key of C, with an indication at the beginning as to how they were to be tuned, as 'Timp. in E♭, B♭,' or 'Timp. in G, D,' etc.; but it is now usual to write the real notes.

To tune drums of the ordinary construction, a key has to be applied successively to each of the several screws that serve to tighten or loosen the head. In French-made drums there is a fixed T-shaped key-head to each screw. But even then it takes some time to effect a change, whence several attempts have been made to enable the performer to tune each drum by a single motion instead of turning seven or eight screws. In Potter's system, the head is acted on by several iron bars following the external curvature of the shell, and converging under it; and they are all drawn simultaneously by a screw turned by the foot of the performer, or by turning the whole drum bodily round.

Cornelius Ward took out a patent in 1837 for the same object. The head is drawn by an endless cord passing over pulleys from the outside to the inside of the drum, where it goes over two nuts, having each two pulleys. These nuts approach and recede from each other by means of a horizontal screw, nearly as long as the diameter of the drum, the handle of which comes just outside the shell, and is turned by the performer whenever he requires to tune the drum. A spring indicator shows the degree of tension of the cord, and consequently the note which the drum will give, so that the performer may tune his instrument by the eye instead of the ear. Gautrot, of Paris, has another plan, viz. a brass hoop fitting closely inside the shell, and pressing against the head. A handle, working a rack and pinion motion, raises or lowers this hoop, and so tunes the drum by altering the pressure against the head. Einbigler, of Frankfort-on-the-Main, makes drums with a similar internal hoop, but worked by a different mechanism; they are used in the theatre of that town.

There will always be some objection to these schemes from the fact of the head being an animal membrane, and consequently not perfectly homogeneous, but requiring a little more or less tension in some part of its circumference, unless, as in Einbigler's drums, there are small screws with fly-nuts all round the upper hoop, for the purpose of correcting any local inequality of tension. Writers on acoustics seem, to have been disheartened by this inequality from extending their experiments on the vibration of membranes. Even Chladni does not pursue the subject very far. We must therefore be content with some empirical formula for determining the proportion which two drums should bear to each other, so that the compass of the larger should be a fourth above that of the smaller. We have already said that the lowest notes of the two drums should be respectivelyKettle-drums in German are called Pauken; in Italian, timpani; in Spanish, atabales; in French, timbales: the two latter evidently from the Arabic tabl and the Persian tambal. There are two very complete Methods for the kettledrums, viz. 'Metodo teorico pratico per Timpani,' by P. Pieranzovini, published at Milan by Ricordi [App. p.618 "Pieranzovini wrote a concerto for the drums"]: and a 'Méthode complète et raisonnée de Timbales,' by Geo. Kastner, published in Paris by Brandus (late Schlesinger).

3. The third kind of drum consists of a wooden or brass cylinder with a skin or head at each end. The skins are lapped round a small hoop, a larger hoop pressing this down. The two large hoops are connected by an endless cord, passing zigzag from hoop to hoop. This cord is tightened by means of leather braces a, b, b. It is slackest when they are all as at a, and tightest when as at b, b. This is called a Side-drum, and is struck

Some side-drums are made much flatter, and are tightened by rods and screws instead of cords.

In orchestras the side-drum is frequently used (and abused) by modern composers. But in the overtures to 'La Gazza Ladra' and 'Fra Diavolo,' the subjects of both being of a semi-military nature, the effect is characteristic and good.

Side-drums are used in the army for keeping time in marching and for various calls, both in barracks and in action. In action, however, bugle-calls are now usually substituted:—

The Drummers' Call.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

The Sergeants' and Corporals' Call.

Commence Firing.

Cease Firing.

The above are examples of drum calls used in the British army; the next is 'La Retraite,' beaten every evening in French garrison towns.

The effect of this is very good when, as may be heard in Paris, it is beaten by twenty-eight drummers. For Berlioz has well observed that a sound, insignificant when heard singly, such as the clink of one or two muskets at 'shoulder arms' or the thud as the butt-end comes to the ground at 'ground arms,' becomes brilliant and attractive if performed by a thousand men simultaneously.

The Tenor-drum is similar to the side-drum, only larger, and has no snares. It serves for rolls in military bands instead of kettle-drums.

The French Tambourin is similar to the last, but very narrow and long. It is used in Provence for dance music. The performer holds it in the same hand as his flageolet (which has only three holes) and beats it with a stick held in the other hand. Auber has used the tambourin in the overture to 'Le Philtre.'

The Bass-drum (Fr. Grosse Caisse, Ital. Gran Cassa or Gran Tamburo) has also two heads, and is played with one stick ending in a soft round knob. It must be struck in the centre of one of the heads. It used to be called the long-drum, and was formerly (in England at least) made long in proportion to its diameter. But now the diameter is increased and the length of the cylinder lessened. The heads are tightened by cords and braces like the side-drum first described, or by rods and screws, or on Cornelius Ward's principle as described for kettle-drums. It is used in military bands and orchestras. There is another sort of bass-drum called a Gong-drum, from its form, which is similar to a gong or to a gigantic tambourine. It is very convenient in orchestras where space is scarce; but it is inferior to the ordinary bass-drum in quality of tone. These instruments do not require tuning, as their sound is sufficiently indefinite to suit any key or any chord. [See Tam-tam.]

Cymbals generally play the same part as the bass-drum; though occasionally, as in the first Allegro of the overture to 'Guillaume Tell,' the bass-drum part is senza piatti (without the cymbals).[ V. de P. ]