A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Key

KEY. A word of manifold signification. It means the scale or system in which modern music is written; the front ends of the levers by which the piano, organ or harmonium are played; the levers which cover or uncover the holes in such instruments as the flute and oboe; lastly, an instruction book or 'Tutor.' English is the only language in which the one term has all these meanings.

I. The systems of music which preceded the modern system, and were developed by degrees into it, were characterised by scales which not only differed from one another in pitch but also in the order of succession of the various intervals of which they were composed. In modern music the number of notes from which a scale can commence is increased by the more minute subdivision of each octave; but each of these notes is capable of being taken as the starting point of the same scale, that is to say of either the major or minor mode, which are the only two distinct scales recognised in modern music. This forms a strong point of contrast between the ancient and modern styles. The old was a system of scales, which differed intrinsically, and thereby afforded facilities for varying qualities of melodic expression; the modern is essentially a system of keys, or relative transposition of identical scales, by which a totally distinct order of effects from the old style is obtained.

The standard scale called the major mode is a series in which semitones occur between the third and fourth and between the seventh and eighth degrees counting from the lowest note, all the other intervals being tones. It is obvious from the irregularity of this distribution that it is not possible for more than one key to be constructed of the same set of notes. In order to distinguish practically between one and another, one series is taken as the normal key and all the others are severally indicated by expressing the amount of difference between them and it. The normal key, which happens more by accident than design to begin on C, is constructed of what are called Naturals, and all such notes in the entire system as do not occur in this series are called Accidentals. In order to assimilate a series which starts from some other note to the series starting from C, it is necessary to indicate the notes alien to the scale of C, which will have to be substituted for such notes in that scale as could not occur in the new series in other words, to indicate the accidentals which will serve that purpose; and from their number the musician at once recognises the note from which his series must start. This note therefore is called the Key-note, and the artificial series of notes resulting from the arrangement is called the Key. Thus to make a series of notes starting from G relatively the same as those starting from C, the F immediately below G will have to be supplemented by an accidental which will give the necessary semitone between the seventh and eighth degrees of the scale. Similarly, D being relatively the same distance from G that G is from C, the same process will have to be gone through again to assimilate the scale starting from D to that starting from C. So that each time a fifth higher is chosen for a key-note a fresh accidental or sharp has to be added immediately below that note, and the number of sharps can always be told by counting the number of fifths which it is necessary to go through to arrive at that note, beginning from the normal C. Thus C—G, G—D, D—A, A—E is the series of four fifths necessary to be gone through in passing from C to E, and the number of sharps in the key of E is therefore four.

Conversely, if notes be chosen in a descending series of fifths, to present new key-notes it will be necessary to flatten the fourth note of the new key to bring the semitone between the third and fourth degrees; and by adopting a similar process to that given above, the number of flats necessary to assimilate the series for any new key-note can be told by the number of fifths passed through in a descending series from the normal C.

In the Minor Mode the most important and universal characteristic is the occurrence of the semitone between the second and third instead of between the third and fourth degrees of the scale, thereby making the interval between the keynote and the third a minor third instead of a major one, from which peculiarity the term 'minor' arises. In former days it was customary to distinguish the modes from one another by speaking of the key-note as having a greater or lesser third, as in Boyce's Collection of Cathedral Music, where the Services are described as in 'the key of B♭ with the greater third' or in 'the key of D with the lesser third,' and so forth. The modifications of the upper part of the scale which accompany this are so variable that no rule for the distribution of the intervals can be given. The opposite requirements of harmony and melody in relation to voices and instruments will not admit of any definite form being taken as the absolute standard of the minor mode; hence the Signatures, or representative groups of accidentals, which are given for the minor modes are really of the nature of a compromise, and are in each case the same as that of the major scale of the note a minor third above the key-note of the minor scale. Such scales are called relatives—relative major and relative minor—because they contain the greatest number of notes in common. Thus A, the minor third below C, is taken as the normal key of the minor mode, and has no signature; and similarly to the distribution of the major mode into keys, each new key-note which is taken a fifth higher will require a new sharp, and each new key-note a fifth lower will require a new flat. Thus E, the fifth above A, will have the signature of one sharp, corresponding to the key of the major scale of G; and D, the fifth below A, will have one flat, corresponding to the key of the major scale of F, and so on. The new sharp in the former case falls on the supertonic of the new key so as to bring the semitone between the second and third degrees of the scale, and the new flat in the latter case falls on the submediant of the new key so as to bring a semitone between the fifth and sixth degrees. The fact that these signatures for the minor mode are only approximations is however rendered obvious by their failing to provide for the leading note, which is a necessity in modern music, and requires to be expressly marked wherever it occurs, in contradiction to the signature.

There is a very common opinion that the tone and effect of different keys is characteristic, and Beethoven himself has given some confirmation to it by several utterances to the point. Thus in one [1]place he writes 'H moll schwarze Tonart,' i.e. B minor, a black key; and, in speaking about [2]Klopstock, says that he is 'always Maestoso! D♭ major!' In a letter to Thomson[3] of Edinburgh (Feb. 19, 1813), speaking of two national songs sent him to arrange, he says, 'You have written them in

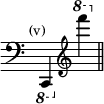

II. KEY (Fr. Touche; Ital. Tasto; Ger. Taste) and KEYBOARD of keyed stringed instruments (Fr. Clavier; Ital. Tastatura; Ger. Claviatur, Tastatur.) A 'key' of a pianoforte or other musical instrument with a keyboard, is a lever, balanced see-saw fashion near its centre, upon a metal pin. It is usually of lime-tree, because that wood is little liable to warp. Besides the metal pin upon the balance rail of the keyframe, modern instruments have another metal pin for each key upon the front rail, to prevent too much lateral motion. A key is long or short according to its employment as a 'natural' or 'sharp,' and will be referred to here accordingly, although in practice a sharp is also a flat, and the written sharp or flat occasionally occurs upon a long key. Each natural is covered as far as it is visible with ivory: and each sharp or raised key bears a block of ebony or other hard black wood. In old instruments the practice in this respect varied, as we shall show presently. In English alone[5] the name 'key' refers to the Latin Clavis, and possibly to the idea of unlocking sound transferred to the lever from the early use of the word to express the written note. The Romance and German names are derived from 'touch.'

A frame or, technically, a 'set' of keys is a keyboard, or clavier according to the French appellation. In German Klavier usually means the keyed stringed instrument itself, of any kind. The influence of the keyboard upon the development of modern music is as conspicuous as it has been important. To this day C major is 'natural' on the keys, as it is in the corresponding notation. Other scales are formed by substituting accidental sharps or flats for naturals both in notation and on the keyed instrument, a fact which is evidence of the common origin and early growth together of the two. But the notation soon outgrew the keyboard. It has been remarked by Professor Huxley that the ingenuity of human inventions has been paralleled by the tenacity with which original forms have been preserved. Although the number of keys within an octave of the keyboard are quite inadequate to render the written notation of the four and twenty major and minor modes, or even of the semitones allied to the one that it was first mainly contrived for, no attempts to augment the number of keys in the octave or to change their familiar disposition have yet succeeded. The permanence of the width of the octave again has been determined by the average span of the hand, and a Ruckers harpsichord of 1614 measures but a small fraction of an inch less in the eight keys, than a Broadwood or Erard concert-grand piano of 1879. We have stated under Clavichord that we are without definite information as to the origin of the keyboard. We do not exactly know where it was introduced or when. What evidence we possess would place the date in the 14th century, and the locality—though much more doubtfully—in or near Venice. The date nearly synchronises with the invention of the clavichord and clavicembalo, and it is possible that it was introduced nearly simultaneously into the organ, although which was first we cannot discover. There is reason to believe that the little portable organ or regal may at first have had a keyboard derived from the T-shaped keys of the Hurdy Gurdy. The first keyboard would be Diatonic, with fluctuating or simultaneous use of the B♭ and B♮ in the doubtful territory between the A and C of the natural scale. But when the row of sharps was introduced, and whether at once or by degrees, we do not know. They are doubtless due to the frequent necessity for transposition, and we find them complete in trustworthy pictorial representations of the 15th century. [App. p.690 "for the oldest illustration of a chromatic keyboard see Spinet, vol. iii. p. 653a, footnote."] There is a painting by Memling in the Hospital of St. John at Bruges, from whence it has never been removed, dated 1479, wherein the keyboard of a regal is depicted exactly as we have it in the arrangement of the upper keys in twos and threes, though the upper keys are of the same light colour as the lower, and are placed farther back.

The oldest keyed instrument we have seen with an undoubtedly original keyboard is a Spinet[6] in the museum of the Conservatoire at Paris, bearing the inscription 'Francisci de Portalupis Veronen. opus, MDXXIII.' The compass is 4 octaves and a half tone (from E to F) and the natural notes are black with the sharps white. [App. p.690 "for the oldest example of a keyboard to a harpsichord or spinet see Spinet, vol. iii. p. 652a, footnote; but Mr. Donaldson's upright spinet from the Correr collection, although undated, is probably, from its structure and decoration, still older. There is a spinet in the loan collection of the Bologna Exhibition (1888) made by Pasi, at Modena, and said to be dated 1490."] The oldest known in England is a similar instrument of the same compass in South Kensington Museum, the work of Annibale Rosso of Milan, dated 1555. As usual in Italy, the naturals are white and the sharps black. The Flemings, especially the Ruckers, oscillated between black and ivory naturals. (We here correct the statement as to their practice in Clavichord, 367b.) The clavichords of Germany and the clavecins of France which we have seen have had black naturals, as, according to Dr. Burney, had those of Spain. Loosemore and the Haywards, in England, in the time of Charles II, used boxwood for naturals; a clavichord of 4½ octaves existing near Hanover in 1875 had the same—a clue perhaps to its date. Keen and Slade in the time of Queen Anne, used ebony. Dr. Burney writes that the Hitchcocks also had ivory naturals in their spinets, and two of Thomas Hitchcock's still existing have them. But one of John Hitchcock's, dated 1630, said to have belonged to the Princess Amelia, and now owned by Mr. W. Dale, has ebony naturals. All three have a strip of the colour of the naturals inserted in the ivory sharps [App. p.690 "omit the word ivory"], and have 5 octaves compass—from G to G, 61 keys! This wide compass for that time—undoubtedly authentic—may be compared with the widest Ruckers to be mentioned further on.

Under Clavichord we have collected what information is trustworthy of the earliest compass of the keyboards of that instrument. The Italian spinets of the 16th century were nearly always of 4 octaves and a semitone, but divided into F and C instruments with the semitone E or B♮ as the lowest note. But this apparent E or B may from analogy with 'short octave' organs—at that time frequently made—have been tuned C or G, the fourth below the next lowest note.[7] Another question arises whether the F or C thus obtained were not actually of the same absolute pitch (as near as pitch can be practically said to be absolute). We know from Arnold Schlick ('Spiegel der Orgelmacher,' 1511; reprinted in 'Monatshifte für Musik-Geschichte,' Berlin, 1869, p. 103) that F and C organs were made on one measurement or pitch for the lowest pipe, and this may have been carried on in spinets, which would account for the old tradition of their being tuned 'in the fifth or the octave,' meaning that difference in the pitch which would arise from such a system.

The Antwerp (Ruckers) harpsichords appear to have varied arbitrarily in the compass of their keyboards. We have observed E—C 45 notes, C—C 49, B—D 52, C—E 53, C—F 54, G—D or A—E 56, G—E or G—F (without the lowest G♯) 58, F—F 61, and in two of Hans Ruckers (the eldest) F—G 63 notes. In some instances however these keyboards have been extended, even, as has been proved, by the makers themselves.

The English seem to have early preferred a wide compass, as with the Hitchcocks, already referred to. Kirkman and Shudi in the next century, however, in their large harpsichords never went higher than F (q), although the latter, towards the end of his career, about 1770, increased his scale downwards to the C (q). Here Kirkman did not follow him. Zumpe began making square pianos in London, about 1766, with the G—F compass (omitting the lowest G♯)—nearly 5 octaves—but soon adopted the 5 octaves, F—F (r), in which John Broadwood, who reconstructed the square piano, followed him. The advances in compass of Messrs. Broadwood and Sons' pianofortes are as follows. In 1793, to 5½ octaves, F to C (s). In 1796, 6 octaves, C to C (t): this was the compass of Beethoven's Broadwood Grand, 1817. In 1804, 6 octaves F to F (u). In 1811, 6½ octaves, C to F (v). In 1844 the treble G was attained, and in 1852 the treble A. But before this the A—A 7-octave compass had been introduced by other makers, and soon after became general. Even C appears in recent concert grands, and composers have written up to it; also the deepest G, which was, by the way, in Broadwoods' Exhibition grands of 1851. (See w, x, y, z). Many however find a difficulty in distinguishing the highest notes, and at least as many in distinguishing the lowest, so that this extreme compass is beyond accurate perception except to a very few.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The invention of a 'symmetrical' keyboard, by which a uniform fingering for all scales, and a more perfect tuning, may be attained, is due to Mr. Bosanquet, of St. John's College, Oxford, who has had constructed an enharmonic harmonium with one. In 'An Elementary Treatise on Musical Intervals and Temperament' (Macmillan, 1876), he has described this instrument—with passing reference to other new keyboards independently invented by Mr. Poole, and more recently by Mr. Colin Brown. The fingering required for Mr. Bosanquet's keyboard agrees with that usual for the A major scale, and (Ib. p. 20) 'any passage, chord, or combination of any kind, has exactly the same form under the fingers, in whatever key it is played.' Here we have the simplicity of the Double Action harp and undoubtedly a great saving in study. In Mr. Bosanquet's harmonium the number of keys in an octave available for a system proceeding by perfect fifths is 53. But in the seven tiers of his keyboard he has 84, for the purpose of facilitating the playing of a 'round' of keys. It is however pretty well agreed, even by acousticians, that the piano had best remain with thirteen keys in the octave, and with tuning according to 'equal temperament.'

In Germany a recent theory of the keyboard has sought not to disturb either the number of keys or the equal temperament. But an arrangement is proposed, almost identical with the 'sequential keyboard' invented and practically tried in England by Mr. William A. B. Lunn under the name of Arthur Wallbridge in 1843, in which six lower and six upper keys are grouped instead of the historical and customary seven and five in the octave. This gives all the major scales in two fingerings, according as a lower or upper key may be the keynote. The note C becomes a black key, and the thumb is more frequently used on the black keys than has been usually permitted with the old keyboard. The latest school of pianists, however, regard the black and white keys as on a level (see Preface to Dr. Hans von Bülow's Selection from Cramer's Studies, 1868) and this has tended to modify opinions on the point. In 1876–7 the partisans of the new German keyboard formed themselves into a society, with the view of settling the still more difficult and vexed question of the reconstruction of musical notation. Thus, discarding all signs for sharps and flats, the five lines of the stave and one ledger line below, correspond to six black fingerkeys for C, D, E, F♯, G♯, A♯, and the four spaces, including the two blanks one above and one below the stave, correspond to six white finger-keys, C♯, D♯, F, G, A, B. Each octave requires a repetition of the stave, and the particular octave is indicated by a number. The keyboard and the stave consequently correspond exactly, black for black and white for white, while the one ledger line shews the break of the octave. And further the pitch for each note, and the exact interval between two notes, for equal temperament, is shewn by the notation as well as on the keyboard. The name of the association is 'Chroma- Verein des gleichstüfigen Tonsystems.' It has published a journal, 'Die Tonkunst' (Berlin, Stilke), edited by Albert Hahn, whose pamphlet, 'Zur neuen Klaviatur' (Königsberg, 1875), with those of Vincent, 'Die Neuklaviatur' (Malchin, 1875) and of Otto Quanz, 'Zur Geschichte der neuen chromatischen Klaviatur' (Berlin, 1877), are important contributions to the literature of the subject. The inventor appears to have been K. B. Schumann, a physician at Rhinow in Brandenburg, who died in 1865, after great personal sacrifices for the promotion of his idea. The pianoforte maker of the society is Preuss of Berlin, who constructs the keyboard with C on a black key; width of octave 14 centimétres,[8] (5¾ inches nearly), and with radiating keys by which a tenth becomes as easy to span as an octave is at present. About sixteen other pianoforte makers are named, and public demonstrations have been given all over Germany. In this system much stress is laid upon C being no longer the privileged key. It will henceforth be no more 'natural' than its neighbours. Whether our old keyboard be destined to yield to such a successor or not, there is very much beautiful piano music of our own time, naturally contrived to fit the form of the hand to it, which it might be very difficult to graft upon another system even if it were more logically simple.

The fact that the fingering of the right hand upwards is frequently that of the left hand downwards has led to the construction of a 'Piano à double claviers renversés,' shown in the Paris Exhibition of 1878 by MM. Mangeot frères of that city. It is in fact two grand pianos, one placed upon the other, with keyboards reversed, as the name indicates, the lower commencing as usual with the lowest bass note at the left hand; the higher having the highest treble note in the same position, so that an ascending scale played upon it proceeds from right to left; the notes running the contrary way to what has always been the normal one. By this somewhat cumbersome contrivance an analogous fingering of similar passages in each hand is secured, with other advantages, in playing extensions and avoiding the crossing of the hands, etc.

[App. p.690 "The last new keyboard (1887–8) is the invention of Herr Paul von Jankó of Totis, Hungary. In this keyboard each note has three finger-keys, one lower than the other, attached to a key lever. Six parallel rows of whole tone intervals are thus produced. In the first row the octave is arranged c, d, e, f♯, g♯, a♯, c; in the second row c♯, d♯, f, g, a, b, c♯. The third row repeats the first, the fourth the second, etc. The sharps are distinguished by black bands intended as a concession to those familiar with the old system. The keys are rounded on both sides and the whole keyboard slants. The advantage Herr von Jankó claims for his keyboard is a freer use of the fingers than is possible with the accepted keyboard, as the player has the choice of three double rows of keys. The longer fingers touch the higher and the shorter the lower keys, an arrangement of special importance for the thumb, which, unlike the latest practice in piano technique, takes its natural position always. All scales, major and minor, can be played with the same positions of the fingers; it is only necessary to raise or lower the hand, in a manner analogous to the violinist's 'shifts.' The facilities with which the key of D♭ major favours the pianist are thus equally at command for D or C major, and certain difficulties of transposition are also obviated. But the octave being brought within the stretch of the sixth of the ordinary keyboard, extensions become of easier grasp, and the use of the arpeggio for wide chords is not so often necessary. The imperfection of balance in the key levers of the old keyboard, which the player unconsciously dominates by scale practice, appears in the new keyboard to be increased by the greater relative distances of finger attack. On account of the contracted measure of the keyboard, the key levers are radiated, and present a fanlike appearance. Herr von Jankó's invention was introduced to the English public by Mr. J. C. Ames at the Portman Rooms on June 20, 1888. It has many adherents in Germany. His pamphlet 'Eine neue Claviatur,' Wetzler, Vienna, 1886, with numerous illustrations of fingering, is worthy of the attention of all students in pianoforte technique."]III. KEYS (Fr. Clefs; Ger. Klappe; Ital. Chiave). The name given to the levers on wind-instruments which serve the purpose of opening and closing certain of the sound-holes. They are divided into Open and Closed keys, according to the function which they perform. In the former case they stand normally above their respective holes, and are closed by the pressure of the finger; whereas in the latter they close the hole until lifted by muscular action. The closed keys are levers of the first, the open keys usually of the third mechanical order. They serve the purpose of bringing distant orifices within the reach of the hand, and of covering apertures which are too large for the last phalanx of the finger. They are inferior to the finger in lacking the delicate sense of touch to which musical expression is in a great measure due. In the Bassoon therefore the sound-holes are bored obliquely in the substance of the wood so as to diminish the divergence of the fingers. Keys are applied to instruments of the Flute family, to Reeds, such as the Oboe and Clarinet, and to instruments with cupped mouthpieces, such as the Key Bugle and the Ophicleide, the name of which is a compound of the Greek words for Snake and Key. [Ophicleide.] In the original Serpent the holes themselves were closed by the pad of the finger, the tube being so curved as to bring them within reach. [Serpent.]

The artistic arrangement of Keys on all classes of wind instruments is a recent development. Flutes, Oboes, Bassoons, and Clarinets, up to the beginning of the present century or even later, were almost devoid of them. The Bassoon however early possessed several in its bass joint for the production of the six lowest notes on its register, which far exceed the reach of the hand. In some earlier specimens, as stated in the article referred to, this mechanism was rudely preceded by plugs, requiring to be drawn out before performance and not easily replaced with the necessary rapidity. [See Bassoon.]

The older Flutes, Clarinets, and Oboes only possess three or four keys at most, cut out of sheet metal, and closely resembling mustard-spoons. The intermediate tones, in this deficiency of keys, were produced by what are termed 'cross-fingerings,' which consist essentially in closing one or two lower holes with the fingers, while leaving one intermediate open. A rude approximation to a semitone was thus attained, but the note is usually of a dull and muffled character. Boehm, in the flute named after him, entirely discarded the use of these 'cross-fingered' notes. [See Flute.]

Keys are now fashioned in a far more artistic and convenient form, a distinction in shape being made between those which are open, and those normally closed; so that the player may be assisted in performance by his instinctive sense of touch. [See Contrafagotto.] [App. p.690 changes this refernce to Double Bassoon."] Besides the Bassoon, the Corno di Bassetto affords a good example of this contrivance, the scale being carried down through four semitones by interlocking keys, worked by the thumb of the right hand alone.- ↑ In a sketch for Cello Sonata, op. 102, No. 2, quoted by Nottebohm.

- ↑ In a conversation with Rochlitz (Für Freunde der Tonkunst iv. 356).

- ↑ Given by Thayer, iii. 45.

- ↑ See a paper by Schumann, 'Charakteristik der Tonarten,' in his 'Gesammelte Schriften,' i. 180.

- ↑ In French, however, the keys of a flute or other wood wind instrument are called clefs.

- ↑ No. 215 of Chouquet's Catalogue (1875).

- ↑ Yet Praetorius distinctly describes the Halberstadt organ, built 1339, re-constructed 1494, as having the lowest note B♮—the scale proceeding by semitones upwards, and we know the sentiment for the leading note had not then been evolved.

- ↑ The width of 6 of the present keys.