A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Musica Ficta

MUSICA FICTA, or Falsa, or Colarata (Cantus fictus), i.e. Feigned, or Artificial Music. One of the earliest discoveries made by the inventors of Figured Music was, the impossibility of writing a really euphonious Counterpoint upon a given Canto fermo, without the use of occasional semitones foreign to the Mode. The employment of such semitones, in Plain Chaunt, was as strictly forbidden by the good taste of all educated Musicians, as by the Bull of Pope John the 22nd. Hence, they were never permitted to appear in the Canto fermo itself. But it soon became evident, that unless they were tolerated in the subordinate parts, no farther progress could be made in a style of composition which was already beginning to attract serious attention. It was indispensable that some provision should be made for the correction of imperfect harmonies; and—as Zarlino justly teaches[1]—Nature's demand for what we should now call a 'Leading-Note' was too strong to be resisted. On these points, a certain amount of concession was claimed by Composers of every School. Nevertheless, the early Contrapuntists yielded so far to prejudice as to refrain from committing their accidentals to writing, whenever they could venture to do so without danger of misconception. Trusting to the Singer for introducing them correctly, at the moment of performance, they indicated them only in doubtful cases for which no Singer could be expected to provide. The older the Part-books we examine, the greater number of accidentals do we find left to be supplied at the Singer's discretion. Music in which they were so supplied was called Cantus fictus, or Musica ficta; and no Chorister's education was considered complete, until he was able to sing Cantus fictus correctly, at sight.

In an age in which the functions of Composer and Singer were almost invariably performed by one and the same person, this arrangement caused no difficulty whatever. So thoroughly was the matter understood, that Palestrina thought it necessary to indicate no more than two accidentals, in the whole of his 'Missa brevis,' though some thirty or forty, at least, are required in the course of the work. He would not have dared to place the same confidence either in the Singers, or the Conductors, of the present day. Too many modern editors think it less troublesome to fill in the necessary accidentals by ear, than to study the laws by which the Old Masters were governed: and ears trained at the Opera are too often but ill qualified to judge what is best suited, either to pure Ecclesiastical Music, or to the genuine Madrigal. Those, therefore, who would really understand the Music of the 15th and 16th centuries, must learn to judge, for themselves, how far the modern editor is justified in adopting the readings with which he presents[2] them: and, to assist them in so doing, we subjoin a few definite rules, collected from the works of Pietro Aron (1529), Zarlino (1558), Zacconi (1596), and some other early writers whose authority is indisputable.

I. The most important of these rules is that which relates to the formation of the Clausula vera, or True Cadence—the natural homologue, notwithstanding certain structural differences, of the Perfect Cadence as used in Modern Music. [See Clausula vera, in Appendix.]

The perfection of this Cadence—which is always associated, either with a point of repose in the phrasing of the music, or a completion of the sense of the words to which it is sung—depends upon three conditions. (a) The Canto fenno, in whatever part it may be placed, must descend one degree upon the Final of the Mode. (b) In the last Chord but one, the Canto fermo must form, with some other part, either a Major Sixth, destined to pass into an Octave; or a Minor Third, to be followed by Unison. (c) One part, and one only, must proceed to the Final by a Semitone—which, indeed, will be the natural result of compliance with the two first-named laws.

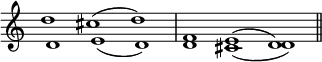

In Modes III, IV, V, VI, XIII, and XIV, it is possible to observe all these conditions, without the use of accidentals. For, in the Third and Fourth Modes, the Canto fermo will naturally tlesc~end a Semitone upon the Final; while, in the others, the Counterpoint will ascend to it by the same interval, as in the following examples, where the Canto fermo is shewn, sometimes in the lower, sometimes in the upper, and sometimes in a middle part, the motion of the two parts essential to the Cadence being indicated by slurs.

Modes III and IV. |

|

Modes V and VI. |

|

Modes XIII and XIV. |

|

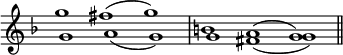

But accidentals will be necessary in all other Modes, whether used at their true pitch, or transposed. (See Modes, the Ecclesiastical.)

Natural Modes |

|

VII and VIII. |

|

IX and X. |

|

Transposed Modes. |

|

VII and VIII. |

|

IX and X. |

|

Moreover, it is sometimes necessary, even in Modes V and VI, to introduce a B♭ in the penultimate Chord, when the Canto fermo is in the lowest part, in order to avoid the False Relation of the Tritonus, which naturally occurs when two Major Thirds are taken upon the step of a Major Second; although, as we have already shewn, it is quite possible, as a general rule, to form the True Cadence, in those Modes, without the aid of Accidentals.

Modes V and VI.

II. In the course of long compositions, True Cadences are occasionally found, ending on some note other than the Final of the Mode. When these occur simultaneously with a definite point of repose in the music, and a full completion of the sense of the words, they must be treated as genuine Cadences in some new Mode to which the Composer must be supposed to have modulated [App. p.722 "for in some new mode to which the composer must be supposed to have modulated, read upon one of the Regular or Conceded Modulations of the Mode in question."]; and the necessary accidentals must be introduced accordingly: as in the Credo of Palestrina's Missa Brevis—

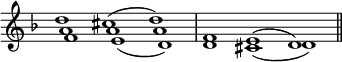

III. An accidental is also frequently needed in the last Chord of a Cadence. The rule is, that every Cadence which either terminates a composition, or concludes a well-defined strain, must end with a Major Chord. It naturally does so in Modes V, VI, VII, VIII, XIII, and XIV. In Modes I, II, III, IV, IX, and X, it must be made to do so by means of an accidental. The Major Third, thus artificially supplied, in Modes in which it would naturally be Minor, is called the 'Tierce de Picardie,' and forms one of the most striking characteristics of Mediaeval Music[3].

Modes I and II. |

|

Modes III and IV. |

|

Modes IX and X. |

|

It is not, however, in the Cadence alone, that the laws of 'Cantus Fictus' are to be observed.

IV. The use of the Augmented Fourth (Tritonus), and the Diminished Fifth (Quinta Falsa), as intervals of melody, is as strictly forbidden in Polyphonic Music, as in Plain Chaunt. [See Mi contra fa.] Whenever, therefore, these intervals occur, they must be made perfect by an accidental; thus—

It will be seen, that, in all these examples, it is the second note that is altered. No Singer could be expected to read so far in advance as to anticipate the necessity for a change in the first note. For such a necessity the text itself will generally be found to provide, and the Singers of the 16th century were quite content that this should be the case; though they felt grievously insulted by an accidental prefixed to the second note, and called it an 'Ass's mark' (Lat. Signum asininum, Germ. Eselszeichen). Even in conjunct passages, they scorned its use; though the obnoxious intervals were as sternly condemned in conjunct as in disjunct movement.

These passages are simple enough: but, sometimes, very doubtful ones occur. For instance, Pietro Aron recommends the Student, in a dilemma like the following, to choose, as the least of two evils, a Tritonus, in conjunct movement, as at (a), rather than a disjunct Quinta falsa, as at (b).

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \clef bass \cadenzaOn \[ f2. g4^"a" a2 b \] e2. f4 g2 r2 \bar "||" }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/a/qarn9rzpq1vlxtmr8kmqowpo37iu8zm/qarn9rzp.png)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \clef bass \cadenzaOn f2. g4 a2 \[ bes2 e2.^"b." \] f4 g2 r \bar "||" }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/i/miir9s9g77f9cp9gm6fpt78azezqh8d/miir9s9g.png)

V. In very long, or crooked passages, the danger of an oversight is vastly increased: and, in order to meet it, it is enacted, by a law of frequent, though not universal application, that a B, between two As—or, in the transposed Modes, an E, between two Ds—must be made flat, thus—

VI. The Quinta falsa is also forbidden, as an element of harmony: and, except when used as a passing note, in the Second and Third Orders of Counterpoint, must always be corrected by an accidental; as in the following example from the Credo of Palestrina's 'Missa Æterna Christi munera.' [See Fa Fictum, in Appendix.]

The Tritonus is not likely to intrude itself, as an integral part of the harmony; since the Chords of 6-4 and 6-4-2 are forbidden in strict Counterpoint, even though the Fourth may be perfect.

VII. But both the Tritonus and Quinta falsa are freely permitted, when they occur among the upper parts of a Chord, the Bass taking no share in their formation. In such cases, therefore, no correction will be required.

VIII. The last rule we think it necessary to mention is strongly enforced by the learned Padre Martini, though Zarlino points out many exceptions to its authority. Its purport is that Imperfect Concords, when they ascend, must be made Major, and, when they descend, Minor. That this is true, in some of the progressions pointed out in the subjoined example, is evident; but, it is equally clear that in others the law is inapplicable.

These laws will suffice to give a fair general idea of a subject, the difficulties of which seem greater, at first sight, than they really are. It is impossible but that we should sometimes meet with ambiguous cases—as, for instance, when it seems uncertain whether a point of repose in the middle of a composition is, or is not, sufficiently well-marked to constitute a True Cadence; or the conclusion of a strain definite enough to demand a Tierce de Picardie. But, a little experience will soon enable the Student to form a correct judgment, whenever a choice is presented to him; if only he will bear in mind that it is always safer to reject a disputed accidental, than to run the risk of inserting a superfluous one.

On one other point, only, will a little farther explanation be necessary.

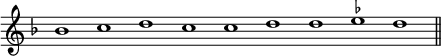

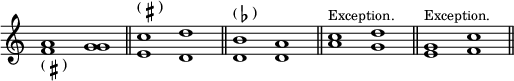

Among the few accidentals introduced into the older Part-books, we rarely find a Natural. Composers limited themselves to the use of the Sharp and Flat, in order to remove a trifling difficulty connected with the process of Transposition. It constantly happens, that, for the convenience of particular Singers, pieces, originally written in transposed Modes, are restored, in performance, to their natural pitch. In this case, the B flat of the transposed scale, raised by a Natural, is represented, at the true pitch, by an F, raised by a Sharp; thus—

| Mode VII, transposed. | Mode VII, restored to its natural pitch. |

|

|

Now, to us, this use of the Natural, in the one case, and the Sharp, in the other, is intelligible enough. But, when accidentals, of all kinds, were exceedingly rare, there was always danger of their being misunderstood: and the early Composers, fearing lest the mere sight of a Natural should tempt the unwary, in the act of transposing, to transfer it from the B to the F, substituted a Sharp for it; thus—

Mode VII, transposed.

- ↑ 'Instituzioni armoniche.' Venice, 1558, p. 222.

- ↑ Proske, in his 'Musica Divina,' has placed all accidentals given or the Composer, in their usual position, before the notes to which they refer: but, those suggested by himself, above the notes. It is much to be desired that all who edit the works of the Old Masters should adopt this most excellent and conscientious plan.

- ↑ Except in compositions in more than four parts, Mediaeval Composers usually omitted the Third, altogether, in the final chord. In this case, a Major Third is always supposed.