A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Point

POINT or DOT (Lat. Punctus, vel Punctum; Ital. Punto; Germ. Punct; Fr. Point). A very antient character, used in mediæval Music for many distinct purposes, though its office is now reduced within narrower limits.

The Points described by Zarlino and various early writers are of four different kinds.

I. The Point of Augmentation, used only in combination with notes naturally Imperfect, was exactly identical, both in form, and effect, with the modern 'Dot'—that is to say, it lengthened the note to which it was appended by one-half, and was necessarily followed by a note equivalent to itself in value, in order to complete the beat. The earliest known allusion to it is to be found in the 'Ars Cantus mensurabilis' of Franco of Cologne, the analogy between whose Tractalus, and the Punctus augmentationis of later writers, is so close that the two may be treated as virtually identical.

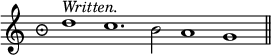

II. The Point of Perfection (Punctus Perfectionis) was used in combination with notes, Perfect by the Time Signature, but rendered Imperfect by Position, for the purpose of restoring their Perfection. In this case, no short note was needed for the purpose of compensation, as the Point itself served to complete the triple beat. Now, in mediæval Music, a Breve, preceded or followed by a Semibreve, or a Semibreve by a Minim, though perfect by virtue of the Time Signature, becomes Imperfect by Position. As the following example is written in the Greater (or Perfect) Prolation, each of its Semibreves is naturally equal to three Minims; but, by the rule we have just set forth, the second and fourth notes become Imperfect by Position—i.e. they are each equal to two Minims only. The fourth note is suffered to remain so, but the second is made Perfect by a Point of Perfection.

The term 'Punctus Perfectionis' is also applied to the Point placed, by mediæval Composers, in the centre of a Circle, or Semicircle, in order to denote either Perfect Time, or the Greater Prolation.

III. The Point of Alteration, or Point of Duplication (Punctus Alterationis, vel Punctus Duplicationis), differs so much, in its effect, from any sign used in modern Music, that it is less easy to make it clear. In order to distinguish it from the Points already described, it is sometimes written a little above the level of the note to which it refers. Some printers, however, so place it, that it is absolutely indistinguishable, by any external sign, from the Point of Augmentation. In such cases it is necessary to remember that the only place in which it can possibly occur is before the first of two short notes, followed by a longer one—or placed between two longer ones—in Perfect Time, or the Greater Prolation; that is to say, in Ternary Rhythm, of whatever kind. But its chief peculiarity lies in its action, which concerns, not the note it follows, but the second of the two short ones which succeed it, the value of which note it doubles—as in the following example, from the old melody, 'L'Homme arme,' in which the note affected by the Point is distinguished by an asterisk.

IV. The Point of Division, sometimes called the Point of Imperfection (Punctus Divisionis, vel Imperfectionis; Divisio Modi), is no less complicated in its effect than that just described, and should also be placed upon a higher level than that of the notes to which it belongs, though, in practice, this precaution is very often neglected. Like the Point of Alteration, it is only used in Ternary Measure; but it differs from the former sign, in being always placed between two short notes, the first of which is preceded, and the second followed, by a long one. Its action is, to render the two long notes Imperfect. But, a long note, in Ternary Rhythm, is always Imperfect by Position, when either preceded or followed by a shorter one: the use of the Points, therefore, in such cases, is altogether supererogatory, and was warmly resented by mediæval Singers, who called all such signs Puncti asinini.

In spite, however, of its apparent complication, the rationale of the Sign is simple enough. An examination of the above passage will show that the Point serves exactly the same purpose as the Bar in modern Music; and we can easily understand that it is called the Point of Division, because it removes all doubt as to the division of the Rhythm into two Ternary Measures.

[ W. S. R. ]