A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Registration

REGISTRATION (or REGISTERING) is the only convenient term for indicating the art of selecting and combining the stops or 'registers' in the organ so as to produce the best effect and contrast of tone, and is to the organ what 'orchestration' is to the orchestra. The stops of an organ may be broadly clased under the two divisions of 'flue-stops' and 'reed-stops.' [See Organ.] The flue-stops again may be regarded as classed under three sub-divisions—those which represent the pure organ tone (as the diapasons, principal, fifteenth, and mixtures), those which aim at an imitation of string or of reed tone (as the violone, viola, gamba, etc.), and those which represent flute tone. In considering the whole of the stops en masse, a distinction may again be drawn between those which are intended to combine in the general tone ('mixing stops') and those, mostly direct imitations of orchestral instruments, which are to be regarded as 'solo stops' to be used for special effects, as the clarinet, orchestral oboe, vox humana, etc. Some stops, such as the harmonic flute, are capable of effective use, with certain limitations, in either capacity.

The use of the pure solo stops is guided by nearly the same æsthetic considerations as the use in the orchestra of the instruments which they imitate [see Orchestration], by suitability of timbre for the expression and feeling of the music. These stops form, however, the smallest and on the whole the least important portion of the instrument.

In the combination of the general mass of stops there are some rules which are invariable—e.g. a 'mutation stop,' such as the twelfth, can never be used without the stop giving the unison tone next above it (the fifteenth), and the mixtures can never be used without the whole or the principal mass of the stops giving the sounds below them, except that on the swell manual the mixture may sometimes be used with the 8-feet stops only, to produce a special effect. On the great-organ manual it is generally assumed that the stops are added in the order in which they are always placed, the unison diapason stops and the 16-feet stops lowest, the principal, twelfth, fifteenth, and mixtures in ascending order above them; and the reeds at the top, to be added last, to give the full power of the instrument. But this general rule has its exceptions for special purposes. If it be desired to play a fugato passage with somewhat of a light violin effect, the fifteenth added to the 8-feet steps, omitting the principal and twelfth, has an excellent effect,[1] more especially if balanced by a light 16-feet stop beneath the diapasons. The 8-feet reeds, again, may be used with the diapasons only, with very fine effect, in slow passages of full harmony. The harmonic flute of 4-feet tone is usually found on the great manual, but should be used with caution. It often has a beautiful effect in addition to the diapasons, floating over them and brightening up their tone, but should be shut off when the 4-feet principal is added, or when the to fifteenth is used, as the two tones do not amalgamate. The 16-feet stops on the manuals are intended to give weight and gravity of tone, and are always admirable with the full or nearly the full organ. In combination with the diapasons only their use is determined by circumstances; with a very full harmony they cause a muddy effect; with an extended harmony in pure parts they impart a desirable fullness and weight of tone, and seem to fill in the interstices of the unison stops: e.g.—

No. 1 would be injured by the addition of a 16-feet stop below the diapasons; No. 2 would improved by it.

The swell organ stops are very like the great organ in miniature, except that the reed-stops predominate more in tone, and are more often used either alone or with diapasons only, the stronger and more pronounced tone of the reeds being requisite to bring out the full effect of the crescendo on opening the swell box. The oboe alone, in passages of slow harmony, has a beautiful effect, rich yet distant. The choir organ is always partially composed of solo stops, and the bulk of its stops are usually designed for special effects when used separately, though with a certain capability of mixing in various combinations. It may be observed that qualities of tone which mix beautifully in unison will often not mix in different octaves. The union of one of the soft reedy-toned stops, of the gamba class, with an 8-feet clarabella flute, has a beautiful creamy effect in harmonised passages, but the addition of a 4-feet flute instead is unsatisfactory; and the combination with the clarabella, though so effective for harmony, would be characterless as a solo combination for a melody. The effect of a light 4-feet flute over a light 8-feet stop of not too marked character is often admirable for the accompanying harmonies to a melody played on another manual; Mendelssohn refers to this in the letter in which he speaks of his delight in playing the accompaniment in Bach's arrangement of the chorale 'Schmücke dich' in this way; the flute, he observes, 'continually floating above the chorale.' This class of effect is peculiar to the organ; it is quite distinct from that of doubling a part with the flute an octave higher in the orchestra; in the organ the whole harmony is doubled, but in so light and blending a manner that the hearer is not conscious of it as a doubling of the parts, but only as a bright and liquid effect.

In contrasting the stops on the different manuals, one manual may be arranged so as to be an echo or light repetition of the other, as when a selection of stops on the swell manual is used as the piano to the forte of a similar selection on the great manual; but more often the object is contrast of tone, especially when the two hands use two manuals simultaneously. In such case the stops must be selected, not only so as to stand out from each other in tone, but so that each class of passage may have the tone best fitted for its character. In this example, from Smart's Theme and Variations in A, for instance—

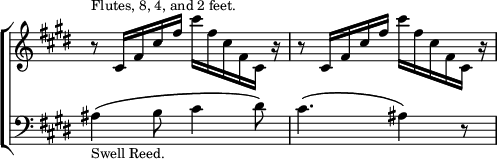

if the registering were reversed, the chords played on the flute-stop and the brilliant accompaniment on the swell reeds, it would not only be ineffective but æsthetically repugnant to the taste, from the sense of the misuse of tone: this of course would be an extreme example of misuse, merely instanced here as typical. The use of flute tone over reed tone on another keyboard is often beautiful in slow passages also; e. g. from [2]Rheinberger's Sonata in F♯:—

where the flute seems to glide like oil over the comparatively rough tones of the reed. Differing tones may sometimes be combined with good effect by coupling two manuals; swell reeds coupled to great-organ diapasons is a fine combination, unfortunately hackneyed by church organists, many of whom are so enamoured of it that they seldom let one hear the pure diapason tone, which it must always be remembered is the real organ tone, and the foundation of the whole instrument. Special expression may sometimes be obtained by special combinations of pitch. Slow harmonies played on 16-feet and 8-feet flutes, or flute-tuned stops, only, produce a very funereal and weird effect.[3] Brilliant scale passages and arpeggios, accompanying a harmony on another keyboard, may be given with an effect at once light and bizarre, with the 16-feet bourdon and the fifteenth three octaves above it. Saint-Saëns, in his first 'Rhapsodie,' writes an arpeggio accompaniment for flutes in three octaves—

though it is perhaps better with the 4-feet flute omitted. The clarinet, though intended as a solo stop, may occasionally be used with great effect in harmonised passages (in combination with a light flue-stop to fill up and blend the tone), and should therefore always be carried through the whole range of the keyboard, not stopped at tenor C, as most builders do with it. The vox-humana should never be combined with any other stop on the same manual; the French organists write it so, but it is a mistake; and, it may be added, it should be but sparingly used at all. It is one of the tricks of organ effect, useful sometimes for a special expression, but very liable to misuse. The modern introduction of a fourth keyboard, the 'solo manual,' entirely for solo stops, puts some new effects in the hands of the player, more especially through the medium of brilliant reed-stops voiced on an extra pressure of wind. These give opportunity for very fine effects in combination with the great-organ manual; sometimes in bringing out a single emphatic note, as in a passage from Bach's A minor Fugue—

* In this case the solo reed is supposed to be coupled to the choir manual (immediately below the great manual), and the lower notes on the treble stave are taken by the first finger of the right hand, the fourth finger of the same hand continuing to hold the E on the lower manual. In some modern organs the solo manual is placed immediately above or below the great manual, in order to facilitate such a combination, which is often exceedingly useful.

where the long blast from the solo reed, sounding above the sway and movement of the other parts, has a magnificent effect. The solo reeds may be used also to give contrast in repeated phrases in full harmony, as in this passage from the finale of Mendelssohn's first Sonata—

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Staff << \key f \major \time 4/4 \partial 2.

\new Voice \relative c'' { \stemUp \[ <c c,>2^\markup \small { "Great Organ" \dynamic ff } bes4 |

<a f> \] \[ <c c,>2^\markup \small \center-column { "Solo Organ" "Reeds." } <b e, c>4 |

<a f c>\] c2^\markup \small "Great Organ." b4 |

a f2 e4 }

\new Voice \relative g' { \stemDown g4 f <e c> _~ |

c g' f s | s <g c> f ~ <f d> | c1 } >>

\new Staff \relative b { \clef bass \key f \major

bes4 a g | r bes a g | r <g bes> <f a> g |

<< { c a g a8 bes } \\ { c,1 } >> }

\new Staff \relative e { \clef bass \key f \major

e4^\markup \small "Pedal." f g | a e f g | a c, d bes | c1 } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/o/noukq4jor2mevjiokpai2l06suzf1hp/noukq4jo.png)

Combinations and effects such as these might be multiplied ad infinitum; in fact, the possible combinations on an organ of the largest size are nearly endless; and it must be observed that organs vary so much in detail of tone and balance, that each large instrument presents to some extent a separate problem to the player.

It is remarkable that in the great organ works of Bach and his school there is hardly an indication of the stops to be employed. It is perhaps on this account that it was long the custom, and is so still with a majority of players, to treat Bach's fugues for the organ as if they were things to be mechanically ground out without any attempt at effect or colouring; as if, as we heard a distinguished player express it, it were sufficient to pull out all the stops of a big organ 'and then wallow in it.' It is no wonder under these circumstances that many people think of organ fugues as essentially 'dry.' The few indications that are given in Bach's works, as in the Toccata in the Doric mode, show, however, that he was fully alive to the value of contrast of tone and effect; and with all the increased mechanical facilities for changing and adjusting the stops in these days, we certainly ought to look for some more intelligent 'scoring' of these great works for the organ, in accordance with their style and character, which is in fact as various as that of any other branch of classical music, and to get rid of the idea that all fugues must necessarily be played as loud as possible. Many of Bach's organ works are susceptible of most delicate and even playful treatment in regard to effect; and nearly all the graver ones contain episodes which seem as if purposely intended to suggest variety of treatment. There must, however, be a distinction made between fugues which have 'episodes,' and fugues which proceed in a regular and unbroken course to a climax. Some of Bach's organ fugues, and nearly all of Mendelssohn's, are of the latter class, and require to be treated accordingly.

In arranging the effective treatment of organ music of this class, it is necessary often to make a special study of the opportunities for changing the stops so as to produce no perceptible break in the flow of the whole. The swell-organ is the most useful bridge for passing from loud to soft back again; when open it should be powerful enough to be passed on to from the great organ without a violent contrast, when the tone can be reduced gradually by closing it; the reverse proceeding being adopted in returning to the great-manual. It is possible to add stops on the great-manual in the course of playing, so as hardly to make any perceptible break, by choosing a moment when only a single note is being sounded; the addition of a stop at that moment is hardly noticed by the hearer, who only finds when the other parts come in again that the tone is more brilliant. If it be a flue-stop that is to be added, a low note is the best opportunity, as the addition of a more acute stop of that class is least felt there; if a reed is to be added, it should be drawn on a high note, as the reed tone is most prominently felt in the lower part of the scale. It should be added that it is absolutely inadmissible to delay or break the tempo to gain time for changing a stop; the player must make his opportunities without any such license.

Tolerably close imitations of orchestral effects are possible on the organ, and an immense number of 'arrangements' of this kind have been but as it is at best but an imperfect imitation, this is not a pursuit to be encouraged. On the other hand, arrangements of piano music for the organ, provided that a careful selection is made of that which is in keeping with the character of the instrument, may often be very interesting and artistically valuable, as giving to the music a larger scale and new beauties of tone and expression, and affording scope for the unfettered exercise of taste and feeling in the invention of effects suitable to the character of the music.

The foregoing remarks may, we hope, afford some answer to the question so often asked by the uninitiated, 'how do you know which stops to use?' but it must be added that a sensitive ear for delicacies of timbre is a gift of which it may be said, nascitur, non fit; and no one will acquire by mere teaching the perception which gives to each passage its most suitable tone-colouring.[ H. H. S. ]