A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Response

RESPONSE, in English church music, is, in its widest sense, any musical sentence sung by the choir at the close of something read or chanted by the minister. The term thus includes the 'Amen' after prayers, the 'Kyrie' after each commandment in the Communion Service, the 'Doxology' to the Gospel, and every reply to a Versicle, or to a Petition, or Suffrage. In its more limited sense the first three of the above divisions would be excluded from the term, and the last-named would fall naturally into the following important groups: (1) those which immediately precede the Psalms, called also the Preces; (2) those following the Apostles' Creed and the Lord's Prayer; (3) those following the Lord's Prayer in the Litany; (4) and the Responses of the first portion of the Litany, which however are of a special musical form which will be fully explained hereafter. Versicles and Responses are either an ancient formula of prayer or praise as, 'Lord, have mercy upon us,' etc., 'Glory be to the Father,' etc., or a quotation from Holy Scripture, as,

R. And our mouth shall shew forth Thy praise.

which is verse 15 of Psalm li; or a quotation from a church hymn, as,

R. And bless Thine inheritance.

which is from the Te Deum; or an adaptation of a prayer to the special purpose, as,

R. O Son of David, have mercy upon us.

The musical treatment of such Versicles and Responses offers a wide and interesting field of study. There can be little doubt that all the inflections or cadences to which they are set have been the gradual development of an original monotonal treatment, which in time was found to be uninteresting and tedious (whence our term of contempt 'monotonous'), or was designedly varied for use on special occasions and during holy seasons. At the time of the Reformation the musical system of the Roman Church, with its distinct and elaborate inflections for Orations, Lections, Chapters, Gospels, Epistles, Antiphons, Introits, etc., etc. [see the article on Plainsong], was completely overthrown, and out of the wreck only a few of the most simple cadences were preserved. Even the response 'Alleluia' was sometimes extended to a considerable length: here is a specimen—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

The word 'Alleluia' is found as a Response in the Prayer-book of 1549, for use between Easter and Trinity, immediately before the Psalms; during the remainder of the year the translation of the word was used. Here is Marbecke's music for it (1550):—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Prayse ye the Lorde

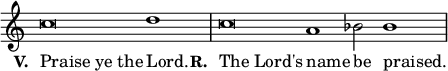

When this was in later editions converted into a Versicle and Response, as in our present Prayer-book, the music was, according to some uses, divided between the Versicle and Response, thus,

But as a matter of fact these 'Preces' in our Prayer-book which precede the daily Psalms have never been strictly bound by the laws of 'ecclesiastical chant,' hence, not only are great varieties of plain-song settings to be met with, gathered from Roman and other uses, but also actual settings in service-form (that is, like a motet), containing contrapuntal devices in four or more parts. Nearly all the best cathedral libraries contain old examples of this elaborate treatment of the Preces, and several have been printed by Dr. Jebb in his 'Choral Responses.'

As then the Preces are somewhat exceptional, we will pass to the more regular Versicles and Responses, such as those after the Apostles' Creed and the Lord's Prayer. And here we at once meet the final 'fall of a minor third,' which is an ancient form of inflection known as the Accentus Medialis:—

This is one of the most characteristic progressions in plain-song versicles, responses, confessions, etc., and was actually introduced by Marbecke into the closing sentences of the Lord's Prayer. It must have already struck the reader that this is nothing more or less than the 'note' of the cuckoo. This fact was probably in Shakespere's mind when he wrote,

The finch, the sparrow, and the lark,

The plain-song cuckoo gray.

This medial accent is only used in Versicles and Responses when the last word is a polysyllable; thus—

When the last word is a monosyllable, there is an additional note, thus—

This may be said to be the only law of the Accentus Ecclesiaaticus which the tradition of our Reformed Church enforces. It is strictly observed in most of our cathedrals, and considering its remarkable simplicity, should never be broken. The word 'prayers' was formerly pronounced as a dissyllable; it therefore took the medial accent thus—

but as a monosyllable it should of course be treated thus—

In comparing our Versicles and Responses with the Latin from which they were translated, it is important to bear this rule as to the 'final word' in mind. Because, the Latin and English of the same Versicle or Response will frequently take different 'accents' in the two languages. For example, the following Versicle takes in the Latin the medial accent; but in the translation will require the moderate accent.

Latin form.

English form.

It has been just stated that the early part of the Litany does not come under the above laws of 'accent.' The principle melodic progression is however closely allied to the above, it having merely an additional note, thus—

This is the old and common Response

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

O ra pro no-bls

and to this are adapted the Responses, 'Spare us, good Lord'; 'Good Lord, deliver us'; 'We beseech Thee to hear us, good Lord'; 'Grant us Thy peace'; 'Have mercy upon us'; 'O Christ hear us' (the first note being omitted as redundant); and 'Lord have mercy upon us; Christ have mercy upon us.' At this point, the entry of the Lord's Prayer brings in the old law of medial and moderate accents; the above simple melody therefore is the true Response for the whole of the first (and principal) portion of the Litany. It is necessary however to return now to the preliminary sentences of the Litany, or the 'Invocations,' as they have been called. Here we find each divided by a colon; and, in consequence, the simple melody last given is lengthened by one note, thus:

This is used without variation for all the Invocations. The asterisk shows the added note, which is set to the syllable immediately preceding the colon. It happens that each of the sentences of Invocation contains in our English version a monosyllable before the colon; but it is not the case in the Latin, therefore both Versicle and Response differ from our use, thus—

Latin.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

In the petitions of the Litany, the note marked with an asterisk is approached by another addition, for instead of

we have—

The whole sentence of music therefore stands thus—

We have now shortly traced the gradual growth of the plain-song of the whole of our Litany, and it is impossible not to admire the simplicity and beauty of its construction.

But the early English church-musicians frequently composed original musical settings of the whole Litany, a considerable number of which have been printed by Dr. Jebb; nearly all however are now obsolete except that by Thomas Wanless (organist of York Minster at the close of the 17th century), which is occasionally to be heard in our northern cathedrals. The plain-song was not always entirely ignored by church-musicians, but it was sometimes included in the tenor part in such a mutilated state as to be hardly recognisable. It is generally admitted that the form in which Tallis' responses have come down to us is very impure, if not incorrect. To such an extent is this the case that in an edition of the 'people's part' of Tallis, published not many years since, the editor (a cathedral organist) fairly gave up the task of finding the plain-song of the response, 'We beseech Thee to hear us, good Lord,' and ordered the people to sing the tuneful superstructure—

It certainly does appear impossible to combine this with

But it appears that this ancient form existed—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Chris - to ex - au - di nos.

This, if used by Tallis, will combine with his harmonies; thus—

Having now described the Preces, Versicles and Responses, and Litany, it only remains to say a few words on (1) Amens, (2) Doxology to Gospel, (3) Responses to the Commandments, all of which we have mentioned as being responses of a less important kind, (1) Since the Reformation but two forms of Amen have been used in our church, the monotone, and the approach by a semitone, generally harmonised thus—

The former of these 'Amens' in early times was used when the choir responded to the priest; the latter, when both priest and choir sang together (as after the Confession, Lord's Prayer, Creed, etc.). Tallis, however, always uses the monotonic form, varying the harmonies thrice. In more modern uses, however, the ancient system has been actually reversed, and (as at St. Paul's Cathedral) the former is only used when priest and choir join; the latter when the choir responds. In many cathedrals no guiding principle is adopted; this is undesirable.

(2) The Doxology to the Gospel is always monotone, the monotone being in the Tenor, thus—

There are, however, almost innumerable original settings of these words used throughout the country.

(3) The Responses to the Commandments are an expansion of the ancient—

Kyrie eleison,

Christe eleison,

Kyrie eleison,

made to serve as ten responses instead of being used as one responsive prayer. The ancient form actually appears in Marbecke (1550), and the so-called Marbecke's 'Kyrie' now used is an editorial manipulation. Being thrown on their own resources for the music to these ten responses, our composers of the reformed church always composed original settings, sometimes containing complete contrapuntal devices. At one period of vicious taste, arrangements of various sentences of music, sacred or secular, were pressed into the service. The 'Jomelli Kyrie' is a good—or rather, a bad—example. It is said to have been adapted by Attwood from a chaconne by Jomelli, which had already been much used on the stage as a soft and slow accompaniment of weird and ghostly scenes. The adaptation of 'Open the heavens' from 'Elijah' is still very popular, and may be considered a favourable specimen of an unfavourable class.

The re-introduction of choral celebrations of Holy Communion has necessitated the use of various inflections, versicles, and responses, of which the music or method of chanting has, almost without exception, been obtained from pre-Reformation sources.