A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Tonic Sol-fa

TONIC SOL-FA is the name of a method of teaching singing which has become popular in England during the last thirty years. It is the method now most generally used in primary schools, and is adopted widely for the training of popular choirs. Its leading principle is that of 'key relationship' (expressed in the word 'Tonic'), and it enforces this by the use of the ancient sound-names, do, re, mi, etc., as visible, as well as oral, symbols. These names are first put before a class of beginners in the form of a printed picture of the scale, called a 'Modulator.' For simplicity's sake they are spelt English-wise, and si is called te to avoid having two names with the same initial letter.

| d1 | f1 | |||

| t | — | m1 | — | l |

| l | — | r1 | — | s |

| s | — | DOH1 | — | f |

| TE | — | m | ||

| f | ta | le | ||

| m | — | LAH | — | r |

| la | se | |||

| r | — | SOH | — | d |

| ba | fe | t1 | ||

| d | — | FAH | ||

| t1 | — | ME | — | l1 |

| ma | re | |||

| l1 | — | RAY | — | s1 |

| de | ||||

| s1 | — | DOH | — | f1 |

| t1 | — | m1 | ||

| f1 | ||||

| m1 | — | l1 | — | r1 |

| r1 | — | s1 | — | d1 |

| t2 | ||||

| d1 | — | f1 | ||

| t2 | — | m1 | — | l2 |

![{ << \new Staff \relative d' { \key d \major \time 4/4 \partial 4 \autoBeamOff

d4^\p | d4. e8 fis4 g | a g8 fis e4 b' | a4.^\markup { \dynamic rf } a8 g4 fis }

\addlyrics { Since first I saw your face I re -- solv'd to hon -- our and re- }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef alto \key d \major \autoBeamOff

d4^\p | d4. d8 d4 d | e e8 e e4 e | fis4.^\markup { \dynamic rf } d8 cis4 d }

\new Staff \relative f { \clef tenor \key d \major \autoBeamOff

fis^\p | fis g a b | cis cis8 cis cis4 b8[( cis)] | d4.^\markup { \dynamic rf } a8 a4 a }

\new Staff \relative d { \clef bass \key d \major \autoBeamOff

d4^\p | d4. d8 d4 b | a a8 a a'4 g | fis4.^\markup { \dynamic rf } fis8 e4 d } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/r/o/ro2yhrw7wcwlpq4x0ftw9a3k0zogdac/ro2yhrw7.png)

| Key D.M. 60. | Thomas Ford. | |||||||||||||||

| p | rf | |||||||||||||||

| Treble. | :d | d | : — .r | m | :f | s | :f | .m | r | :l | s | :— | s | f | :m | |

| 1. Since | first | I | saw | your | face, | I | re - | solv'd | To | hon | - | our | and | re- | ||

| Alto. | :d | d | : — .d | d | :d | r | :r | .r | r | :r | m | :— | .d | t1 | :d | |

| Tenor. | :m | m | : f | s | :l | t | :t | .t | t | :l .t | d1 | :— | .s | s | :s | |

| 2. The | sun, | whose | beams | most | glo - | ri - | ous | are, | Re- | ject | - | eth | no | be- | ||

| Bass. | :d | d | : — .d | d | :l1 | s1 | :s1 | .s1 | s | :f | m | :— | .m | r | :d | |

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

��nown you; If now I b dis-dain'd. I wish my cres. pp

heart had ne-ver known you.

This constant insistance on the scale and nothing but the scale carries the singer with ease over the critical difficulties of modulation. He has been taught to follow with his voice the teacher's pointer as it moves up and down the modulator. When it touches soh (see the modulator above) he sings soh. It moves to the doh on the same level to the right, and he sings the same sound to this new name. As he follows the pointer up and down the new scale he is soon taught to understand that a new sound is wanted to be the te of the new doh, and thus learns, by the 'feeling' of the sounds, not by any mere machinery of symbols, what modulation is. When he has been made familiar with the change from scale to scale on the modulator, he finds in the printed music a sign to indicate every change of key. Thus the changes between tonic and dominant in the following chant are shown as follows (taking the soprano part only):—

Robinson.

| Key E♭. | Key B♭. | f. Key E♭ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 𝄐 | 𝄐 | 𝄐 | 𝄐 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | | s | | | d1 | :l | | | s | :— | || | ml | | | t | :d1 | | | d1 | :t | | | d1 | :— | || | d1s | | | f | :m | | | l | :— | || | s | | | r | :m | | | r | :r | | | d | :—|| |

the ml meaning that the singer is to sing the sound which is the me of the scale in which he began, but to call it lah while singing it, and sing onwards accordingly. When the key changes again to the original tonic he is informed of it by the ds, which means that he is to sing again the sound he has just sung as doh, but to think of it and sing it as soh. These indications of change of key give the singer direct notice of what, in the Staff notation, he is left to find out inferentially from the occurrence of a sharp or flat in one of the parts, or by comparing his own part with the others. To make these inferences with any certainty requires a considerable knowledge of music, and if they are not made with certainty the 'reading' must be mere guess-work. Remembering that in music of ordinary difficulty—say in Handel's choruses—the key changes at an average every eight or ten bars, one can easily see what an advantage the Tonic Sol-faist has in thus being made at every moment sure of the key he is singing in. The method thus sweeps out of the beginner's way various complications which would puzzle him in the Staff notation 'signatures,' 'sharps and flats,' varieties of clef. To transpose, for instance, the above chant into the key of F, all that is needed is to write 'Key F' in place of 'Key E♭.' Thus the singer finds all keys equally easy. 'Accidentals' are wholly unknown to him, except in the comparatively rare case of the accidental properly so called, that is, a 'chromatic' sound, one not signifying change of key.[2]

These advantages can, it is true, be in part secured by a discreet use of the 'tonic' principle,—a 'moveable do' with the staff notation. But the advocates of the letter notation urge that the old notation hampers both teacher and learner with difficulties which keep the principle out of view: that the notes of the staff give only a fictitious view of interval.

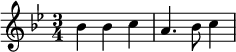

The question of the utility of a new notation is thus narrowed to a practical issue: one which may be well left to be determined by teachers themselves. It is of course chimerical to suppose that the ancient written language of music could be now 'disestablished,' but musicians need not object to, they will rather welcome, any means of removing difficulties out of the learner's way. The universal language of music—and we are apt to forget how much we owe to the fact that it is universal—may well be said to be almost a miracle of adaptation to its varied uses; but it is worth observing that there is an essential difference between the sight-reader's and the player's use of any system of musical signs. The player has not to think of the sounds he makes before he makes them. When he sees, say, the symbol  its meaning to him is not, in practice, 'imagine such and such a sound,' but 'do something on your instrument which will make the sound.' To the pianist it means 'touch a certain white key lying between two black keys'; to the violoncellist, 'put the middle finger down on the first string,' and so on. The player's mental judgment of the sound only comes in after it has been produced. By this he 'checks' the accuracy of the result. The singer, on the contrary, knows nothing of the mechanical action of his own throat: it would be useless to say to him, 'make your vocal chords perform 256 vibrations in a second.' He has to think of the sound first; when he has thought of it, he utters it spontaneously. The imagination of the sound is all in all. An indication of absolute pitch only is useless to him, because the melodic effect, the only effect the memory can recall, depends not on absolute but on relative pitch. Hence a 'tonic' notation, or a notation which can be used tonic-ally, can alone serve his purpose.

its meaning to him is not, in practice, 'imagine such and such a sound,' but 'do something on your instrument which will make the sound.' To the pianist it means 'touch a certain white key lying between two black keys'; to the violoncellist, 'put the middle finger down on the first string,' and so on. The player's mental judgment of the sound only comes in after it has been produced. By this he 'checks' the accuracy of the result. The singer, on the contrary, knows nothing of the mechanical action of his own throat: it would be useless to say to him, 'make your vocal chords perform 256 vibrations in a second.' He has to think of the sound first; when he has thought of it, he utters it spontaneously. The imagination of the sound is all in all. An indication of absolute pitch only is useless to him, because the melodic effect, the only effect the memory can recall, depends not on absolute but on relative pitch. Hence a 'tonic' notation, or a notation which can be used tonic-ally, can alone serve his purpose.

An exposition of the details of the method would be here out of place, but one or two points of special interest may be noticed.[3] One is the treatment of the minor scale—a crux of all Sol-fa systems, if not of musical theory generally. Tonic Sol-faists are taught to regard a minor scale as a variant of the relative major, not of the tonic major, and to sol-fa the sounds accordingly. The learner is made to feel that the special 'minor' character results from the dominance of the lah, which he already knows as the plaintive sound of the scale. The 'sharpened sixth' (reckoning from the lah), when it occurs, is called ba (the only wholly new sound-name used (see the modulator, above), and the 'leading' tone is called se, by analogy with te (Italian si) of the major mode. Thus the air is written and sung as follows:—

| Key B♭. Lah is C. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| l1 If |

d :t1 God |

:l1 be |

m for |

:m us, |

:l who |

s can |

:— | .l be |

:f a- |

m gainst |

:l1 us? |

: | : | : | : | :l1 who |

m can |

:— | .r be |

:d a- |

t1 gainst |

:l1 us? |

:d who |

s can |

:— | .f be |

:m a- |

r gainst |

:d us? |

: |

Experience appears to show that, for sight-reading purposes, this is the simplest way of treating the minor mode. Some musicians object to it on the ground that, as in a minor scale the lowest (and highest) sound is essentially a tonic, in the sense that it plays a part analogous to that of the do in a major scale, calling it la seems an inconsistency. But this seems a shadowy objection. The only important question is, what sign, for oral and ocular use, will best help the singer to recognise, by association with mental effect, one sound as distinguished from another? Experience shows that the Tonic Sol-fa plan does this effectually. The method is also theoretically sound. It proceeds on the principle that similarity of name should accord with similarity of musical effect. Now as a fact the scale of A minor is far more closely allied to the scale of C major than it is to the scale of A major. The identity of 'signature' itself shows that the substantial identity of the two first-named scales has always been recognised. But a proof more effective than any inference from signs and names is that given by the practice of composers in the matter of modulation. The scales most nearly related must evidently be those between which modulation is most frequent; and changes between tonic major and relative minor (type, C major to and from A minor) are many times more frequent than the changes between tonic major and tonic minor (type, C major to and from C minor). In Handel's music, for instance, the proportion is some nine or ten to one.[4] If therefore the Tonic Sol-faist, in passing from C major to A minor, changed his doh, he would be adopting a new set of names for what is, as near as may be, the same set of sounds.

The examples above given show the notation as applied to simple passages; the following will show how peculiar or difficult modulations may be rendered in it:—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

They stand be - fore God's throne, and serve him day and night. And the Lamb shall lead them to foun - tains of liv - ing wa - ters.

Af - fright - ed fled hell's spi - rits black in throngs. Down they sink in the deep a - byss to end - less night.

In the teaching of Harmony the Tonic Sol-fa method puts forward no new theory, but it uses a chord-nomenclature which makes the expression of the facts of harmony very simple. Each chord is represented by the initial letter, printed in capitals, of the sol-fa name of its essential root, thus—

the various positions of the same chord being distinguished by small letters appended to the capital, thus—

Harmony being wholly a matter of relative, not absolute pitch, a notation based on key-relationship has obvious advantages as a means of indicating chord-movements. The learner has from the first been used to think and speak of every sound by its place in a scale, and the familiar symbols m, f, etc. convey to him at once all that is expressed by the generalising terms 'mediant,' 'subdominant,' etc. Another point in the method, as applied to Harmony teaching, is the prominence given to training the ear, as well as the eye, to recognise chords. Pupils are taught, in class, to observe for themselves how the various consonances and dissonances sound; and they are practised at naming chords when sung to them.

The Tonic Sol-fa method began to attract public notice about the year 1850. Its great success has been mainly due to the energy and enthusiasm of Mr. John Curwen, who died in June 1880, after devoting the best part of his life to the work of spreading knowledge of music among the people. Mr. Curwen [see Curwen, Appendix], born in 1816, was a Nonconformist minister, and it was from his interest in school and congregational singing that he was led to take up the subject of teaching to sing at sight. His system grew out of his adoption of a plan of Sol-faing from a modulator with a letter notation, which was being used with success for teaching children some forty years ago, by a benevolent lady living at Norwich. He always spoke of this lady, Miss Elizabeth Glover (d. 1867), as the originator of the method. Her rough idea developed under his hand into a complete method of teaching. He had a remarkable gift for explaining principles in a simple way, and his books strike the reader throughout by their strong flavour of common sense and incessant appeal to the intelligence of the pupil. They abound with acute and suggestive hints on the art of teaching: and nothing, perhaps, has more contributed to the great success of the method than the power which it has shown of making teachers easily. A wide system of examinations and graduated 'certificates,' a college for training teachers, and the direction of a large organisation were Mr. Curwen's special work. [See Tonic Sol-fa College.] For some time the system was looked on with suspicion and disfavour by musicians, chiefly on account of the novel look of the printed music, but the growing importance of its practical results secured the adhesion of musicians of authority. Helmholtz, viewing it from the scientific as well as the practical side, remarked in his great work on Sound (1863) on the value of the notation as 'giving prominence to what is of the greatest importance to the singer, the relation of each tone to the tonic,' and described how he had been astonished—'mich in Erstaunen setzen'—by the 'certainty' with which 'a class of 40 children, between 8 and 12 in a British and Foreign school, read the notes, and by the accuracy of their intonation.'[5] The critical objection which the Tonic Sol-faists have to meet is, that the pupil on turning to the use of the Staff notation has to learn a fresh set of signs. Their reply to this is, that as a fact two-thirds of those who become sight-singers from the letter notation, spontaneously learn to read from the staff. They have learnt, it is said, 'the thing music,' something which is independent of any system of marks on paper; and the transition to a set of new symbols is a matter which costs hardly any trouble. With their habitual dependence on the scale they have only to be told that such a line of the staff is doh, and hence that the next two lines above are me and soh, and they are at home on the staff as they were on the modulator. The testimony of musicians and choirmasters confirms this.[6] Dr. Stainer, for instance, says (in advocating the use of the method in schools): 'I find that those who have a talent for music soon master the Staff notation after they have learnt the Tonic Sol-fa, and become in time good musicians. It is therefore quite a mistake to suppose that by teaching the Tonic Sol-fa system you are discouraging the acquisition (the future acquisition) of Staff music, and so doing a damage to high art. It may be said, if the systems so complement one another, Why do you not teach both? But from the time that can be devoted to musical instruction in schools it is absurd to think of trying to teach two systems at once. That being so, then you must choose one, and your choice should be governed by the consideration of which is the simpler for young persons, and there cannot be a doubt which is the simpler.' This testimony is supported by a general consensus of practical teachers. The London School Board find that 'all the teachers prefer to teach by the Tonic Sol-fa method,' and have accordingly adopted it throughout their schools; and it now appears that of the children in English primary schools who are taught to sing by note at all, a very large proportion (some 80 per cent) learn on this plan. In far too many schools still, the children only learn tunes by memory, but the practicability of a real teaching of music has been proved, and there is now fair hope that ere long the mass of the population may learn to sing. The following figures, from a parliamentary return of the 'Number of Departments' in primary schools in which singing is taught (1880–1), is interesting. They tell a tale of lamentable deficiency, but show in what direction progress may be hoped for:—

| By Ear. | Hullah's System. |

Tonic Sol-fa. | Old Notation: Moveable Do. |

More than one System. | |

| School Board Schools (England and Wales) | 4681 | 86 | 1414 | 84 | 1 |

| Other Schools (England and Wales) | 17470 | 628 | 1278 | 607 | 31 |

| Schools in Scotland | 1280 | 8 | 1648 | 111 | 19 |

Writing down a tune sung by a teacher has now become a familiar school exercise for English children, a thing once thought only possible to advanced musicians; and it has become common to see a choir two or three thousand strong singing in public, at first sight, an anthem or part-song fresh from the printer's hands. Such things were unknown not many years back. In the great spread of musical knowledge among the people this method has played a foremost part, and the teaching of the elements is far from being all that is done. Some of the best choral singing now to be heard in England is that of Tonic Sol-fa choirs. The music so printed includes not only an immense quantity of part-songs, madrigals, and class-pieces, but all or nearly all the music of the highest class fit for choral use—the oratorios of Handel, masses by Haydn and Mozart, cantatas of Bach, etc. One firm alone has printed, it is stated, more than 16,000 pages of music. Leading English music-publishers find it desirable to issue Tonic Sol-fa editions of choral works, as do the publishers of the most popular hymn-books. Of a Tonic Sol-fa edition of the 'Messiah,' in vocal score, 39,000 copies have been sold.

To the pushing forward of this great and beneficent work of spreading the love and knowledge of music, Mr. Curwen devoted his whole life, and seldom has a life been spent more nobly for the general good. He was a man of singularly generous nature, and in controversy, of which he naturally had much, he was remarkable for the perfect candour and good temper with which he met attack. If the worth of a man is to be measured by the amount of delight he is the means of giving to the world, few would be ranked higher than Mr. Curwen. His was a far-reaching work. Not only has it been, in England, the great moving force in helping on the revival of music as a popular enjoyment, but it has had a like effect in other great communities. We read of the forming of choral classes, in numbers unknown before, in New Zealand, Canada, Australia, India, the United States. Even from savage and semi-savage regions—Zululand or Madagascar—come accounts of choral concerts. When one thinks of what all this means, of the many hard-working people all over the world who have thus been taught, in a simple way, to enter into the enjoyment of the music of Handel or Mendelssohn, of the thousands of lives brightened by the possession of a new delight, one might write on the monument of this modest and unselfish worker the words of the Greek poet: 'The joys that he hath given to others who shall declare the tale thereof.'[7]

Of the 'Galin-Chevé' method of teaching sight-reading, which is based, broadly speaking, on the same principle as the Tonic Sol-fa method, a notice is given under Chevé, in the Appendix.[ R. B. L. ]

- ↑ Sir John Herschel said in 1868 (Quarterly Journal of Science, art. 'Musical Scales')—'I adhere throughout to the good old system of representing by Do, Re, Mi, Fa, etc., the scale of natural notes in any key whatever, taking Do for the key-note, whatever that may be, in opposition to the practice lately introduced (and soon I hope to be exploded) of taking Do to represent one fixed tone C,—the greatest retrograde step, in my opinion, ever taken in teaching music, or any other branch of knowledge.'

- ↑ In the Soprano part, for instance, of the Messiah choruses there are but three real 'accidentals.'

- ↑ The best summary account of this system for the musician is given in 'Tonic Sol Fa,' one of the 'Music Primers' edited by Dr. Stainer (Novello).

- ↑ In 'Judas' the transitions from major to relative minor, and from minor to relative major, are, as reckoned by the writer, 67 in number; the transitions from major to tonic minor, and from minor to tonic major, being only 7. The practice of centuries in points of technical nomenclature cannot, of course, be reversed, but it is plain that the phrase 'relative' minor is deceptive. The scale called 'A minor' would be more reasonably called (as its signature in effect calls it) C minor. It has not been sufficiently noticed that the different kinds of change from minor to major are used by composers to produce strikingly different effects. The change to relative major (e.g. A minor to C major) is the ordinary means of passing, say, from the dim to the bright—from pathetic to cheerful. But the change to tonic major (A minor to A major) is a change to the intensely bright—to jubilation or triumph. A good instance Is the beginning of the great fugue in 'Judas,' 'We worship God'—a point of extraordinary force. Another is the well-known choral finale in 'Mosé in Egitto,' 'Dal tuo stellate soglio,' where, after the repetition in three successive verses of the change from G minor to B♭ major, giving an effect of reposeful serenity, the culminating effect, the great burst of triumph in the last verse, is given by the change from G minor to G major. Other instances are the passage in 'Elijah'—'His mercies on thousands fall'—and the long prepared change to the tonic major which begins the finale of Beethoven's C minor Symphony.

- ↑ Tonempfindung, App. XVIII. (Ellis p. 639). Professor Helmholtz confirmed this experience in conversation with the writer in 1881.

- ↑ It is stated that of 2025 pupils who took the 'Intermediate Certificate' in a particular year, 1327 'did so with the optional requirement of singing a hymn-tune at sight from the Staff-notation.'

- ↑

ἐπεὶ ψάμμος ἀριθμὸν περιπέφευγεν'

ἐκεῖνος ὅσα χάρματ' ἄλλοις ἕθηκεν,

τίς ἄν φράσαι δύναιτο;Pindar