Archaeologia/Volume 38/On the Occurrence of Flint Implements in undisturbed Beds of Gravel, Sand, and Clay

XX. On the Occurrence of Flint Implements in undisturbed Beds of Gravel, Sand, and Clay. By John Evans, Esq. F.S.A., F.G.S.

Read June 2nd, 1859.

The natural connection between Geology and Archæology has at various times been pointed out by more than one writer[1] on each subject; and it must, indeed, be apparent to all who consider that both sciences treat of time past as compared with time present. The one, indeed, merges by almost imperceptible degrees in the other; while the object of both is, from the examination of ancient remains, to recall into an ideal existence days long since passed away, to trace the conditions of a previous state of things, and, as it were, to repeople the earth with its former inhabitants.

The antiquary, as well as the geologist, has "from a few detached facts to fill up a living picture; so to identify himself with the past as to describe and follow, as though an eye-witness, the changes which have at various periods taken place upon the earth."[2] Geology is, in fact, but an elder brother of archæology, and it is therefore by no means surprising to find that the one may occasionally lend the other brotherly assistance; although it has been generally supposed that the last of the great geological changes took place at a period long antecedent to the appearance of man upon the earth, and that the modifications of the earth's surface of which he has been a witness have been—with the exception of those due directly to volcanic agency—but trifling and immaterial.

The subject of the present paper—the discovery of flint implements wrought by the hand of man, in what are certainly undisturbed beds of gravel, sand, and clay, both on the continent and in this country—tends to show that such an opinion is erroneous; and that in this region of the globe, at least, its surface has undergone far greater vicissitudes since man's creation than has hitherto been imagined. A discovery of this kind must of necessity be of great interest both to the geologist, as affording an approximate date for the formation of these superficial beds of drift, and as exemplifying the changes which the fauna of this region has undergone since man appeared among its occupants; and also to the antiquary, as furnishing the earliest relics of the human race with which he can hope to become acquainted relics of tribes of apparently so remote a period, that—

Antiquity appears to have begun

Long after their primeval race was run.

But beyond the limited circle of those peculiarly interested in geology or archæology, this discovery will claim the especial attention of all who, whether on ethnological, philological, or theological grounds, are interested in the great question of the antiquity of man upon the earth.

It is, however, mainly from the antiquarian point of view that I intend now to regard it, though, for the better elucidation of the circumstances under which these implements have been found, it will be necessary to enter into various geological details.

It is now some years since a distinguished French antiquary, M. Boucher de Perthes, in his work, entitled, "Antiquités Celtiques et Antédiluviennes,"[3] called attention to the discovery of flint implements fashioned by the hand of man in the pits worked for sand and gravel in the neighbourhood of Abbeville, in such positions, and at such a depth below the surface of the ground, as to force upon him the conclusion that they were found in the very spots in which they had been deposited at the period of the formation of the beds containing them. The announcement by M. Boucher de Perthes, of his having discovered these flint implements under such remarkable circumstances was, however, accompanied by an account of the finding of many other forms of flint of a much more questionable character, and by the enunciation of theories which by many may have been considered as founded upon too small a basis of ascertained facts. It is probably owing to this cause that, neither in France nor in this country, did the less disputable and now completely substantiated discoveries of M. de Perthes receive from men of science in former years the attention to which they were justly entitled.

The question whether man had or had not coexisted with the extinct pachydermatous and other mammals, whose bones are so frequently found in the more recent geological deposits, had indeed already more than once been brought under the notice of scientific inquirers by the discovery of flint flakes and implements, and fragments of rude pottery, in conjunction with the remains of these animals in several ossiferous caverns both in England and on the continent.[4] Among the former may be mentioned Kent's Cavern near Torquay, and among the latter those of Bize, of Pondres, and Souvignargues, and those on the banks of the Meuse, near Liège, explored by Dr. Schmerling, where human bones were also found, apparently washed in at the same time as the bones of the extinct quadrupeds.[5] In some ossiferous caves in the Brazils similar discoveries had also been made by Dr. Lund and M. Claussen, and, from the condition and situation of the human remains, Dr. Lund concluded that they had belonged to an ancient tribe that was coeval with some of the extinct mammalia.

But it was always felt that there was a degree of uncertainty attaching to the evidence derived from the deposits in caverns, owing to the possibility of the relics of two or more entirely distinct periods becoming intermixed in such localities, either by the action of water or by the operations of the primitive human occupants of the caves, which prevented any judgment being firmly founded upon it.

Attention has however been lately again called to this question by the fact, that, in the excavations which have been carried on under the auspices of the Royal and Geological Societies in the cave at Brixham in Devonshire, worked flints, apparently arrow-heads and spear-heads, have been discovered in juxtaposition with the bones of the Rhinoceros tichorhinus, Ursus speæus, Hyæna spelæa, and other extinct animals.[6] One flint implement in particular was met with immediately beneath a fine antler of a reindeer and a bone of the cave bear, which were imbedded in the superficial stalagmite in the middle of the cave.

In addition to this, investigations have been made by Dr. H. Falconer in the Grotta di Maccagnone near Palermo, where, imbedded in a calcareous breccia beneath the stalactitic covering of the roof, he observed "coprolites of the Hyæna, splinters of bone, teeth of ruminants and the genus Equus, together with comminuted fragments of shells, bits of carbon, specks of argillaceous matter resembling burnt clay, and fragments of shaped siliceous objects." These objects in flint closely resemble the obsidian knives from Mexico, and the flint knives or flakes so frequently found in all parts of the world ; and it is to be remarked that, though they were in considerable abundance in the breccia, any amorphous fragments of flint were comparatively rare, and no pebbles or blocks occurred either within or without the cave; so that there could be but little doubt of the flint flakes being of human workmanship.[7]

The question of the co-existence of man with the extinct animals of the Drift period being thus revived, Mr. Joseph Prestwich, F.R.S., a distinguished geologist, who for years has devoted his principal attention to the more recent geological formations, determined to proceed to Abbeville and investigate on the spot the discoveries of M. Boucher de Perthes, and invited me and several other Fellows of the Geological Society to accompany him. The others were unfortunately prevented from doing so; but at the end of April, 1859, I joined Mr. Prestwich at Abbeville, and with him inspected the collections of M. de Perthes (to whose courtesy and hospitality we were largely indebted), and also visited in his company several of the pits worked for gravel and sand in the neighbourhood of both Abbeville and Amiens, in which the flints in question were asserted to have been found.

Both these towns are situated upon the upper chalk, which is, however, overlaid, as is frequently the case, by beds of drift of a much later period. I need hardly say that drift is the term applied by geologists to those superficial deposits of sands, gravels, clays, and loams which we find to have been spread out over the older rocks in many districts by the driving action of currents of water, whether salt or fresh, or by the drifting action of ice. Though all belonging to a late geological period (the newer Pleiocene, or Pleistocene), these beds of drift are of various and distinct ages, and may be said to range from a point of time antecedent to the Glacial period, when nearly the whole of Britain was submerged beneath an ocean of arctic temperature, to the time when the surface of the earth received its present configuration, and even down to the present day; for the alluvium of existing rivers may be considered equivalent to the fresh-water drift of an earlier age.

The drift-beds occurring in different localities in the neighbourhood of Abbeville and Amiens, do not appear to have been all deposited at the same time, but to be of at least two distinct ages; the series on the lower level being distinguished by the occurrence within it of the bones and teeth of the Elephas primigenius, or Siberian mammoth, and of other extinct animals. These mammaliferous beds of sand, loam, and gravel extend over a considerable tract of country on the slopes of the valley of the Somme, and are worked in several localities for the repair of the roads and for building purposes.

The most notable places in the neighbourhood of Abbeville, where the gravel has been extensively excavated, are at the spot where is now the Champ de Mars, the pit near the Moulin Quignon, and that near the Porte St. Gilles; but the beds of gravel are spread over a large area, and are said to be continuous from the Moulin Quignon on the south-east of the town, and about ninety feet above the level of the river Somme, to the suburb of Menchecourt on the north-west of Abbeville, where the beds assume a much more arenaceous character, and where sand has been dug in immense quantities at a level but little more than twenty feet above that of the Somme.

At St. Roch, a suburb of Amiens, the deposit is also at a low level, like that at Menchecourt, and at both places large quantities of teeth and bones of the Elephas primigenius, Rhinoceros tichorhinus, and other extinct animals, have been found.

In another locality, on the opposite side of Amiens to St. Roch, at the pits near the seminary of St. Acheul, the drift occurs at a higher level, viz. about ninety feet above the river Somme at that part of its course, or about one hundred and sixty feet above the sea. The depth of the beds, which consist of brick earth, sand, and gravel, arranged in layers of variable thickness, but with some approach to stratification, is here from twenty to twenty-five feet.

The following section was taken by Mr. Prestwich,[8] showing the beds in their descending order:—- 1. Brown brick-earth, loam, and clay, with an irregular bed of flint gravel near its base. No organic remains10 to 15 feet.

(Divisional plane between 1 and 2, very uneven and indented.)

- 2. Whitish marl and quartzose sand, with small chalk grit. Land and fresh-water shells (Lymnæa, Succinea, Helix, Bithinia, Planorbis, Pupa, Pisidium, and Ancylus, all of recent species,) are common; mammalian bones and teeth are occasionally found.2 to 8 feet.

- 3. Coarse subangular gravel, white, with irregular ochreous and ferruginous seams, and with tertiary flint pebbles and sandstone blocks. Remains of shells similar to those last mentioned in patches of sand; teeth and bones of the elephant, and of a species of horse, ox, and deer, generally in the lower part of the bed. It reposes on an uneven surface of chalk.6 to 12 feet.

One of the pits occupies the site of a Gallo-Roman cemetery, which appears to have continued in use for some centuries: large stone coffins, and the iron cramps of those in wood, are of frequent occurrence, hut personal ornaments are rarely met with. Roman coins are found from time to time, some as early as the reign of Claudius, and I purchased from one of the workmen a second-brass coin of Magnentius, with the letters AMB in the exergue, showing that it had been struck at AMBIANVM, the name given in late Roman times to the neighbouring town of Amiens, which by the Gauls was known as SAMAROBRIVA.

At the Moulin Quignon near Abbeville, which is near the summit of a hill of no great elevation, the beds of drift are more ochreous and more purely gravelly in their nature than at St. Acheul, and their thickness is about ten or twelve feet. In this case also they rest upon an irregular surface of chalk; and in the lower part of the beds, at but a slight distance above the chalk, occasionally accompanied by the bones and teeth of the Siberian mammoth and other animals, flints shaped by the hand of man are alleged to have been found. At Menchecourt, the beds of sand and loam attain a thickness of from twenty to thirty feet; and in a layer of flints at their base, among which are found shells, land and fresh water as well as marine, have also been discovered a number of mammalian remains, together with flints showing traces of the hand of man upon them.

The following is the section of the pit at Menchecourt, as taken by Mr. Prestwich:—- 1. A mass of brown sandy clay, with angular fragments of flints and chalk rubble. No organic remains. Base very irregular and indented into bed No. 2.

2 to 12 feet.

- 2. A light-coloured sandy clay (sable à plaquer of the workmen), analogous to the loess, containing land shells (Pupa, Helix, Clausilia,) of recent species

8 to 25 feet.

- 3. White sand (sable aigre) with one to two feet of subangular flint gravel at base. This bed abounds in land and fresh-water shells of recent species of the genera Helix, Succinea, Cyclas, Pisidium, Valvata, Bithinia, and Planorbis, together with the marine Buccinum undatum, Cardium edule, Littorina rudis, Tellina solidula, and Purpura lapillus. With them have also been found the Cyrena consobrina, and numerous mammalian remains.

2 to 6 feet.

- 4. Light-coloured sandy marl, in places very hard, with Helix, Zonites, Succinea, and Pupa. Not traversed.

3 feet.

The flint implements are said also to occur occasionally in the beds of sandy clay above the white sand, but the pit has of late years been but little worked, and in consequence the implements but rarely found. In the section of the Menchecourt beds given by M. Boucher de Perthes,[9] the place where two of the worked flints were found is shown at about thirty feet from the surface, and another was discovered at about fourteen feet; they are, however, said to have been most commonly met with in the lower beds. At the Moulin Quignon, the Porte St. Gilles, and at other places in the arrondissement of Abbeville, as for instance at Yonval, the gravel-pit at Mareuil, the sand-pit at Drucat and at St. Riquier, similar flint implements are stated by M. de Perthes[10] to have been found under similar circumstances; but these last-mentioned places I have not visited.

The whole of the drift which I have described is of fluviatile origin; and in the beds of sand and clay, land and fresh water shells of existing species are frequently found in abundance, though at Menchecourt, as has been already mentioned, they are mixed with others of marine origin, which gives more of an estuarine character to the deposit at that place.

I think that it is by no means impossible that these arenaceous beds at Menchecourt may eventually be proved to be rather subsequent in date to the higher and more gravelly beds at the Champ de Mars, and Moulin Quignon, on the opposite side of Abbeville; their elevation above the river Somme is not much more than from twenty to thirty feet, so that under ordinary circumstances it might be considered by some, that they are due to its action under a state of things not very materially different from that at present existing, did not the mammalian remains, found at both Menchecourt and St. Roch, point to an entirely different fauna from that of the present day. In any case, as it is but reasonable to suppose the drift deposits on the higher slopes of the valley to be at least coeval with those at the bottom, even if not of greater antiquity, the mammalian remains of the lower deposits become of extreme importance, as a means of ascertaining the age of those at a higher level, from which precisely similar remains may be absent. This is, however, a purely geological question, into which I need not at present enter.

Mr. Prestwich, in the able Memoir upon this subject which he has communicated to the Royal Society, has gone so fully into the geological features of this part of the valley of the Somme, that any further details are needless, and I shall therefore content myself with this very general sketch of the position of the drift at Abbeville and Amiens, and refer those who desire further information to the paper by Mr. Prestwich in the Philosophical Transactions. I will merely add, that he considers that the gravel at St. Acheul closely resembles that on some parts of the Sussex coast, while the beds at the Moulin Quignon are nearly analogous to those near the East Croydon Station, and in many parts of the valley of the Thames.

Of the animals now for the most part extinct, and most of which have hitherto been regarded as having ceased to exist before the appearance of man upon the earth, and the bones of which have been discovered in the drift at Menchecourt, the following may be mentioned on the authority of M. de Perthes' "Antiquités Celtiques et Antédiluviennes," and M. Buteux' "Esquisse Géologique du Département de la Somme:"—

Elephas primigenius (Siberian mammoth).

Rhinoceros tichorhinus.

Ursus spelæus.

Felis spelæa?

Hyæna spelæa.

Cervus tarandus priscus.

Cervus Somonensis.

Bos primigenius.

Equus fossilis?

The mammalian remains from St. Acheul, and other places where bones have been found in the drift of the valley of the Somme, represent the same group, though confined to a smaller number of different species in any one locality. At St. Roch the teeth of the hippopotamus have also been recently found. The remains of the same group of animals have been met with in the cave at Brixham, and in that called Kent's Cavern, near Torquay, to which I have already alluded, and are constantly brought to light in the superficial freshwater drift which abounds in many parts of this country. The rhinoceros and mammoth belong to the same species as those whose frozen bodies, still retaining their flesh, skin, and hair, have been discovered beneath the ice-bound soil of Siberia. Both species appear to have been adapted for a far colder climate than their present congeners.

Let us now turn our attention to the flint implements alleged to have been discovered in the drift in company with the remains of what has usually been regarded an older world; and consider, first, how far in material, form, and workmanship they agree with or differ from the stone weapons and implements so commonly found throughout Europe; and then enter upon an examination of the evidence of the circumstances of their finding, and the means at our command for ascertaining their degree of antiquity.

That they really are implements fashioned by the hand of man, a single glance at a collection of them placed side by side, so as to show the analogy of form of the various specimens, would, I think, be sufficient to convince even the most sceptical. There is a uniformity of shape, a correctness of outline, and a sharpness about the cutting edges and points, which cannot be due to anything but design;[11] so that I need not stay to combat the opinion that might otherwise possibly have arisen that the weapon-like shapes of the flints were due to some natural configuration, or arose from some inherent tendency to a peculiar form of fracture. A glance at the Plates will suffice to satisfy upon this point those who have not had an opportunity of examining the implements themselves.

The material of which they have been formed, flint derived from the chalk, is the same as has been employed for the manufacture of cutting implements by uncivilized man in all ages, in countries where flint is to be found. Its hardness, and the readiness with which it may be fractured so as to present a cutting edge, have made it to be much in request among savage tribes for this purpose; and in some instances[12] flint appears to have been brought from a distance when not found upon the spot. There is therefore nothing to distinguish these implements from the drift, as far as material is concerned, from those which have been called celts, except, perhaps, that the flints have not been selected with such care, nor are they so free from flaws as those from which the ordinary flint weapons of the Stone period were fashioned. There is, however, this to be remarked, that the aboriginal tribes of the Stone period made use of other stones besides flint, such as greenstone, syenite, porphyry, clay-slate, jade, &c., whereas the weapons from the drift are, as far as has hitherto been ascertained, exclusively of flint. As to form, the implements from the drift may, for convenience sake, be classed under three heads, though there is so much variety among them that the classes, especially the second and third, may be said to blend or run one into the other. The classification I propose is as follows—

1. Flint flakes, apparently intended for arrow-heads or knives.

2. Pointed weapons, some probably lance or spear-heads.

3. Oval or almond-shaped implements, presenting a cutting edge all round.

In M. de Perthes' museum, and in the engravings of his "Antiquités Celtiques et Antédiluviennes," many other forms of what he considers to be implements may be seen, but upon them the traces of the hand of man are to my mind less certain in character. The flints resembling in form various animals, birds, and other objects, must I think be regarded as the effect of accidental concretion and of the peculiar colouring and fracture of flint, rather than as designedly fashioned. This is, however, a question into which I need not enter, as it in no way affects that now before us. Suffice it that there exists an abundance of implements found in the drift which are evidently the work of the hand of man, and that their formation cannot possibly be regarded as the effect of accident or the result of natural causes. When once their degree of antiquity has been satisfactorily proved, it will be a matter for further investigation whether there are not other traces to be found of the race of men who fashioned these implements, besides the implements themselves.

These objects I must now consider in the order proposed, with reference to their analogies and differences in form, when compared with those of what, for convenience sake, I will call the Stone period.

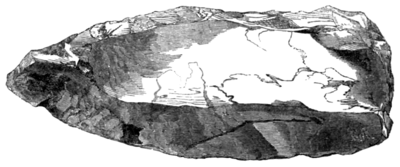

There is a considerable resemblance between the flint flakes apparently intended for arrow-heads and knives (the first of the classes into which I have divided the implements), and those which when found in this country, or on the continent, are regarded as belonging to a period but slightly prehistoric. The fact is, that wherever flint is used as a material from which implements are fashioned, many of the flakes or splinters arising from the chipping of the flint, are certain to present sharp points or cutting edges, which by a race of men living principally by the chase are equally certain to be regarded as fitting points for their darts or arrows, or as useful for cutting purposes; they are so readily formed, and are so well adapted for such uses without any further fashioning, that they have been employed in all ages just as struck from off the flint. The very simplicity of their form will, however, prevent those fabricated at the earliest period from being distinguishable from those made at the present day, provided no change has taken place in the surface of the flint by long exposure to some chemical influence. As also they are produced most frequently by a single blow, it is at all times difficult, among a mass of flints, to distinguish those flakes formed accidentally by natural causes, from those which have been made by the hand of man; an experienced eye will indeed arrive at an approximately correct judgment, but from the causes I have mentioned, mere flakes of flint, however analogous to what we know to have been made by human art, can never be accepted as conclusive evidence of the work of man, unless found in sufficient quantities, or under such circumstances, as to prove design in their formation, by their number or position. Flint flakes apparently intended for arrow-heads and knives have been found in the sands and gravel near Abbeville, and some were dug out of the sand at Menchecourt, in the presence of Mr. Prestwich, quite at the bottom of the beds of sand. One from this locality is here engraved:—

Occasionally they are of larger size, and have been chipped into shape at the point, so as nearly to resemble the implements of the next class.

An argument may be derived in favour of the majority of these arrow-head-shaped flakes having been designedly made, not only from their similarity in form one to another, but also because the existence of more carefully fashioned flint implements almost necessarily implies the formation and use of these simpler weapons by the same race of men who were skilful enough to chip out the more difficult forms. But though probably the work of man, and though closely resembling the flakes of flint which have been considered as affording evidence of man's existence when found in ossiferous caverns, this class of implements is not of much importance in the present branch of our inquiry ; because, granting them to be of human work and not the result of accident, there is little by which to distinguish them from similar implements of more recent date.

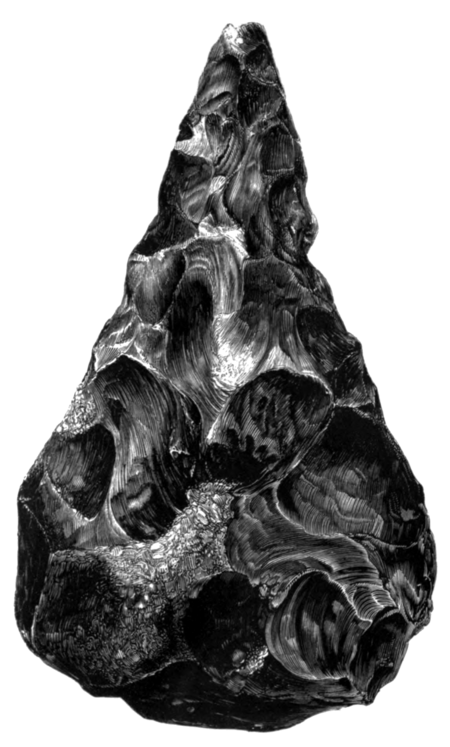

The case is different with the implements of the second class, those analogous in form to spear or lance heads. Of these there are two varieties, the one with a Plate XV.

These spear-shaped weapons from the drift are, on the contrary, not at all adapted for insertion into a socket, but are better calculated to be tied to a shaft or handle, with a stop or bracket behind their truncated end. Many of them, indeed, seem to have been intended for use without any handle at all, the rounded end of the flints from which they were formed having been left unchipped, and presenting a sort of natural handle. It is nearly useless to speculate on the purposes to which they were applied; but attached to poles they would prove formidable weapons for encounter with man or the larger animals, either in close conflict or thrown from a distance as darts. It has been suggested by M. de Perthes, that some of them may have been used merely as wedges for splitting wood, or, again, they may have been employed in grubbing for esculent roots, or tilling the ground, assuming that the race who formed them was sufficiently advanced in civilisation. This much I think may be said of them with certainty, that they are not analogous in form with any of the ordinary implements of the so-called Stone period.

The same remark holds good with regard to the third class into which I have divided these implements, viz. those with a cutting edge all round (Pl. XV. No. 3). In general contour they are usually oval, with one end more sharply curved than the other, and occasionally coming to a sharp point, but there is a considerable variety in their form, arising probably from defects in the flints from which they were shaped; the ruling idea is, however, that of the oval, more or less pointed. They are generally almost equally convex on the two sides, and in length vary from two to eight or nine inches, though for the most part only about four or five inches long. The implements of this form appear to be most abundant in the neighbourhood of Abbeville, where that engraved was found; while those of the spear-shape prevail near Amiens, where both the specimens shown in the Plate were procured.

It is to be remarked that among the implements discovered in the cavern called Kent's Hole, near Torquay, were some identical in form with those of the oval type from Abbeville.

As before observed, in character they do not resemble any of the ordinary stone implements with which I am acquainted, though I believe some few of these also present a cutting edge all round,[13] but at the same time are much thinner, and more triangular than oval or almond-shaped in their form.

The implements most analogous in their oval form to those now under discussion, are some of those found in the mounds or barrows of the valley of the Mississippi, in several of which enormous numbers of lance heads and arrow heads have been discovered. In one of these mounds, within an earthwork on the north fork of Point Creek, there were found, arranged in an orderly manner in layers, some thousands of discs chipped out of hornstone, "some nearly round, others in the form of spear heads; they were of various sizes, but for the most part about six inches long by four wide, and three quarters of an inch or an inch in thickness." From the account given at p. 214, vol. i. of the Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, it would appear that these weapons were merely roughly blocked out, as if to be afterwards worked into more finished forms, of which many specimens are found: but in the rough-hewn implements shown by the woodcuts in the abovementioned work, there is a very close resemblance to some of the Abbeville forms, though the edges are more jagged.

As to the use which this class of flint implements from the drift was originally intended to fulfil, it is hard to speculate. The workmen who find them usually consider them to have been sling-stones, and such some of the smaller sizes may possibly have been, whether propelled from an ordinary sling or from the end of a cleft stick; many, however, seem to be too large for such a purpose, and were more probably intended for axes cutting at either end, with the handle securely bound round the middle of the stone, and if so there would be a reason why it might be desirable to have one end more pointed than the other, so that one instrument could be applied to two kinds of work. M. de Perthes has suggested, that they might also have been mounted as hatchets by insertion in a socket scooped out in a handle.

But all this is conjecture. In point of workmanship, I think it will be perceived that the weapons or implements now under consideration differ considerably from those of the so-called Stone period: of these latter, by far the greater number (with the exception of arrow heads) are more or less ground, and even polished; some with the utmost care all over, but nearly all ground sufficiently to ensure a clean cutting edge. The implements from the drift are, on the contrary so far as has been hitherto observed, never ground, but their edges left in the rough state in which they have been chipped from the flint.

The manner in which they have been fashioned appears to have been by blows from a rounded pebble mounted as a hammer, administered directly upon the edge of the implements, so as to strike off flakes on either side. At all events I have by this means reproduced some of the forms in flint, and the edges of the implements thus made present precisely the same character of fracture as those from the drift.

In instances where (either from having been left accidentally unfinished, or from never having been intended to be ground,) the weapons of the Stone period have remained in their rough-hewn state, it will be observed that, with very few exceptions, they are chipped out with a greater nicety and accuracy, and with a nearer approach to an even surface, than those from the drift, and, rude as they may appear, point to a higher degree of civilisation than that of the race of men by whom these primitive weapons or implements were formed.

There is indeed a class of flint implements, which are stated to have been found in the peat deposits on the banks of the Somme, which in point of rudeness of workmanship appear to equal these more ancient forms from the beds of drift, though for the most part essentially different in shape; I have not, however, given sufficient attention to them to speak with confidence as to their precise character, and will not complicate the question by making further allusion to them.

I think that enough has been said to make it apparent to all who have made a study of the stone implements usually found (those of the so-called Stone period) that the spear-heads and sling-stones, or axes, or by whatever name they are to be called, which are now brought under their notice, have but little in common with the types already well known ; they will therefore be prepared to receive with less distrust the evidence I shall adduce, that they are found under circumstances which show that, in all probability, the race of men who fashioned them must have passed away long before this portion of the earth was occupied by the primitive tribes by whom the more polished forms of stone weapons were fabricated, in what we have hitherto regarded as remote antiquity.

I come, therefore, to the important question, how is it proved that these implements are actually found in beds of really undisturbed clay, gravel, or sand, and have not been introduced or buried at some period subsequent to the formation of the inclosing beds? The evidence is of two kinds, direct and circumstantial; and this I will now examine, giving the direct evidence, as being the more valuable, precedence. We have then, in the first place, that of M. Boucher de Perthes, the original discoverer of this class of implements, who, through evil report and good report, has delivered his constant testimony to the fact of their being discovered, in nearly all cases, in undisturbed drift, and usually at a considerable depth below the surface. That some few may have been discovered in ground that has been moved, or near the surface, in no way militates against the fact that the majority of them have been found in undisturbed soil. It only shows, what might have been expected, that the soil containing these implements may have been moved without their having attracted sufficient attention for them to have been picked out from it, or, in cases where they have occasionally been found in other and more recent soils, that they had been at some time picked out from the gravel, sand, or clay, and afterwards thrown away. For M. Boucher de Perthes' detailed account of his discoveries, I must refer the reader to his work already cited.

Scattered through its pages are notices giving full particulars of the finding of numbers of the weapons, and in M. de Perthes' museum are innumerable specimens, with the nature of their matrix of soil and the depth at which they were found, (many of them under his own eyes,) marked upon them. Procès-verbaux of many of the discoveries were taken at the time, and some are printed in the volumes referred to.[14] Nothing could be stronger than M. de Perthes' verbal assurances to Mr. Prestwich and myself of the finding of these implements in undisturbed gravels and sands, and occasionally clay, sometimes at depths of from twenty feet to thirty feet below the surface, and usually in beds at but a slight distance above the chalk. The testimony of other French geologists and antiquaries may also be adduced both as to the geological character of the beds and the fact of the flint implements being incorporated in them. M. Douchet, M.D.,[15] of Amiens, appears to have been the first discoverer of them at St. Acheul, and he addressed a memoir to the French Institute, expressing his firm conviction upon the subject. The printed testimony of M. de Massy and others is also brought forward by M. Boucher de Perthes,[16] in the book above cited; but the most important evidence is that of Dr. Rigollot, who received the distinction of being elected a Corresponding Member of the Institute but shortly before his death in 1856. In his "Mémoire sur des Instruments en Silex trouvés à St. Acheul, près Amiens," published in 1855, he enters fully into the question of the nature of the drift and the part of the beds in which the worked flints are found, and states distinctly that, after the most careful examination, he came to the conclusion that these implements are at St. Acheul found exclusively in the true drift, which incloses the remains of the extinct mammals, and at a depth of ten feet and more from the surface.

Of the accuracy of all these concurrent statements the experience of Mr. Prestwich and myself fully convinced us, and we had, moreover, the opportunity of seeing one at least of the worked flints in situ, at the gravel-pit near St. Acheul. Mr. Prestwich, who had been there a day or two previously, had left instructions with the workmen that in case of their discovering one of these "langues de chat" imbedded in the gravel it was to be left untouched, and he was at once to be apprized. The announcement of such a discovery was accordingly telegraphed to us at Abbeville, and the following morning we proceeded to Amiens, where we were joined by MM. Dufour and Gamier, the President and Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries of Picardy, who accompanied us to the pit near St. Acheul. There, at a depth of eleven feet from the surface, and about four feet six inches from the bottom of the pit, in the bank or wall of gravel, was an implement of the second class that I have described, its narrower edge projecting, and itself for the greater part dovetailed into the gravel. It was lying in a horizontal position, and the gravel around it hard and compact, and in such a condition that it was quite impossible that the implement could have been inserted into it by the workmen for the sake of reward. The beds above it consisting of rudely stratified gravel, sand, and clay, presenting a vertical face, showed not the slightest traces of having been disturbed, with the exception of the twelve or eighteen inches of surface soil, and the lines of the division between the beds were entirely unbroken; so much so that their different characters can be recognised on a photograph of the section taken for Mr. Prestwich. Besides the langue de chat thus seen in situ, the workmen in the pit supplied us with a considerable number of these implements, as well as with some of the oval form, and gratefully received a trifling recompense in return. They shewed us the spots where they said several of them had been found (two of them that morning, at the depth of fifteen and nineteen feet respectively from the surface), and there appeared no reason to doubt their assertions. I may add, that since our return Mr. Prestwich, in company with some other geologists, has revisited Amiens, and that one of the party, Mr. J. W. Flower, uncovered and exhumed with his own hands a most perfectly worked instrument of the lance-head form, at a depth of twenty feet from the surface. The party brought away, as the result of their one day's visit, upwards of thirty of the implements, which had been collected by the workmen.[17] From the manner in which these pits are worked, there is always a "head," or "face," of earth, which shows an excellent section of the soil; and any places where at any former time pits have been sunk or excavations made, (as, for instance, in the ancient cemetery of St. Acheul,) are, owing to the rough stratification of the beds, readily discovered. The workmen in the pits, both at Amiens and Abbeville, gave concurrent testimony of the usually undisturbed nature of the soil, and to the fact of the flint implements being generally found in the lower part of the beds, where also the fossil bones and teeth are principally discovered.

It may be observed that in the beds of brick-earth and sand overlying the gravel at St. Acheul are numerous freshwater shells, some of them of so fragile a character that they must have been destroyed had the soil at any time been moved.

The fossil bones are of comparatively rare occurrence in the gravel pits, but the number of the flint implements that has been found is almost beyond belief. Dr. Rigollot states that in the pits of St. Acheul, between August and December 1854, above four hundred specimens were obtained; and now, whenever the gravel is being extensively dug, hardly a day passes without one or two being found. This very abundance, for which however it is difficult to account, affords a secondary proof of the undisturbed nature of the drift; for how could such numbers of flint weapons have been introduced at any period subsequent to the formation of the drift, and yet leave no evident traces of the manner in which they were buried? They appear, too, to be detached and scattered through the mass of gravel, with no indications of their having been buried there with any design, but rather as if their positions were the result of the merest accident. Another remarkable piece of circumstantial evidence, is the discovery of implements and weapons of similar form under precisely similar circumstances, but by different persons, at Abbeville and Amiens, some thirty miles apart; though the discoveries are not limited to these two spots, but have also been subsequently made in various localities in that district, where there have been excavations in the drift. It is, however, only in such excavations that they have been found; which would not have been the case had their presence in the gravel been owing to their interment by human agency; for, supposing it possible that some unknown race of men had been seized with a desire to bury their implements at a depth of from ten to twenty feet below the surface, they would hardly have selected for this purpose the hardest and most impracticable soil in their neighbourhood, a gravel so hard and compact as to require the use of a pickaxe to move it.

In the cultivated soil and made ground above, and at much less depth from the surface, ground and polished instruments, evidently belonging to the so-called Stone period, have indeed been found; but this again only tends to prove that the shaped flints discovered at a much greater depth belonged to some other race of men, and inasmuch as they certainly are not the work of a subsequent people, we have here again a testimony that they must be referred to some antecedent race, which had perished perhaps ages before the Celtic occupation of the country. The similarity in form between the flint implements from the drift, and those found in the cave-deposits that I have previously mentioned, is also a circumstance well worthy of observation.

Again, many of the implements have a coating of carbonate of lime forming an adherent incrustation upon them: this, as M. Douchet has already remarked, is for these weapons what the patina is for bronze coins and statues, a proof of their antiquity. The incrustation occurs on all the flints in certain beds of the gravel, and is probably owing to the percolation of water among them, charged with calcareous matter derived from the chalky sands above, which it has gradually deposited upon the flints and pebbles. It has probably been a work of time, commencing soon after the formation of the beds, and possibly is still going on. If, therefore, the flint implements had been introduced into these beds at a subsequent date to the other flints and pebbles which are found with them, we might expect them to be either free from incrustation, or at all events with less calcareous matter upon them; neither of these appears, however, to be the case, but all the flints in these particular layers, whether worked or not, are similarly incrusted. The presence of the coating upon them also proves that the weapons were really extracted by the workmen from the beds in which they state them to have been found, and that they are not derived from the upper beds or surface soil.

Another similar proof is found in the discolouration of the surface of the implements. It is well known that flints become coloured, often to a considerable depth from their surface, by the infiltration of colouring matter from the matrix in which they have been lying, or from some molecular change, due probably to chemical action. If these implements had been deposited among the beds of gravel, sand, or clay at some later period than the other flints adjacent to them, it might be expected that some difference in colour would testify to their more recent introduction; but in all cases, as far as I was able to ascertain, these worked flints were discoloured in precisely the same way as the rough flints in the same positions. Among the more ochreous beds they are stained of a reddish brown tint to some depth below their surface; in the clay they have undergone some change of condition, and have become white and in appearance like porcelain; while those which have been imbedded in the calcareous sands have remained nearly unaltered in colour.

This evidence, like that of the calcareous coating, is of value in two ways, both as proving the length of time that the implements must have been imbedded in the matrix, and also as corroborating the assertions of the workmen with regard to their positions when found. Some few of the implements present a more or less rubbed and water-worn appearance; a more convincing proof than this, of these flint implements having been deposited where found by the drifting action of water, can hardly be conceived. Apart from this, the chain of evidence adduced must I think be sufficient to convince others, as I confess it did me, that the conclusions at which Mons. de Perthes had arrived upon this subject were correct, and that these worked flints were as much original component parts of the gravel, as any of the other stones of which it consists.[18]

But how much more fully was this conviction brought home to my mind, when on my return to England I found that discoveries of precisely similar weapons and implements had been made under precisely similar circumstances in this country, and placed on record upwards of sixty years ago.

In the 13th Volume of the Archæologia, p. 204, is an account of Flint Weapons discovered at Hoxne in Suffolk, communicated by John Frere, Esq., F.R.S. and F.S.A., read June 22, 1797, and illustrated by two Plates showing two of the weapons, closely resembling in form that from Amiens, Plate XV. No. 2. Those engraved, as well as some other specimens, were presented to this Society, and are still preserved in our Museum. They are so identical in character with some of those from the valley of the Somme, that they might be supposed to have been made by the same hand. Mr. Frere remarks, that they are evidently weapons of war, fabricated and used by a people who had not the use of metals, and that, if not particularly objects of curiosity in themselves, they must be considered in that light from the situation in which they were found. He says, that they lay in great numbers at a depth of about twelve feet in a stratified soil, which was dug into for the purpose of raising clay for bricks, the strata being disposed horizontally, and presenting their edges to the abrupt termination of high ground.

The section is described by him as follows:—- 1. Vegetable earth112 feet.

- 2. Argill (brick-earth)712 feet.

- 3. Sand mixed with shells and other marine substances1 foot.

- 4. A gravelly soil, in which the flints are found, generally at the rate of five or six in a square yard2 feet.

The analogy between this section and some that might be adduced from the neighbourhood of Abbeville or Amiens is remarkable; and here also the weapons are stated to have been found in gravel underlying brick-earth.

To make the analogy more complete, "in the stratum of sand (No. 3) were found some extraordinary bones, particularly a jaw-bone of enormous size, with the teeth remaining in it," which was presented, together with a huge thigh-bone found in the same place, to Sir Ashton Lever.

I at once communicated so remarkable a confirmation of our views to Mr. Prestwich, who lost no time in proceeding to Hoxne, to which place I have also paid subsequent visits in his company. We found the brick-field there still in operation, but the section of course considerably altered since the time when Mr. Frere visited it. Where they were digging at the time when we saw the pit for the first time the section was as follows:—- 1. Surface-soil and a few flints2ft.

- 2. Brick-earth, consisting of a light brown sandy clay, divided by an irregular layer of carbonaceous clay12 ft.

- 3. Yellow sand and sub-angular gravel6 in. to 1 ft.

- 4. Grey clay, in places peaty, and containing bones, wood, and fresh-water and land shells2 to 4 ft.

- 5. Sub-angular flint gravel2 ft.

- 6. Blue clay, containing fresh-water shells10 ft.

- 7. Peaty clay, with much woody matter6 ft.

- 8. Hard clay1 ft.

The thickness of these latter beds we ascertained by boring, as the pit is not worked below the bed of clay No. 4. The shells are all of existing species of fresh-water and land mollusca, such as Unio, Planorbis, Succinea, Bithinia, Valvata, Pisidium, Cyclas, and Helix; and are not, as Mr. Frere had supposed, of marine origin.

An old workman in the pit at once recognised one of the French implements shown him, and said that many such were formerly found there in a bed of gravel, which, in the part of the pit formerly worked, attained occasionally a thickness of three to four feet. The large bones and flint weapons were found indiscriminately mixed up in this bed. Bones are still frequently met with in the bed of clay No. 4, and Mr. T. E. Amyot, of Diss, whose father was for many years Treasurer of this Society, has an astragalus of an elephant which was found here, it is believed in this bed, and also various other mammalian remains from this pit.

During the winter of 1858-59 the workmen had discovered two of the flint implements (to which they gave the appropriate name of fighting stones), one of which Mr. Prestwich recovered from a heap of stones in the pit. It is more of the oval than of the spear-head form. Since that time several other specimens have been discovered, principally in the bed of brick-earth No. 2. Numerous other weapons which have been exhumed at Hoxne in former years are preserved in various collections, but there is no record of the exact positions in which they were found. At Hoxne, however, as well as at Amiens, I have had ocular testimony on this point; for in the gravel thrown out from a trench dug under our own supervision, I myself found one of the implements of the spear-head type, from which however the point had been unfortunately broken by the workmen in digging.

It must have lain at a depth of about eight feet from the surface, and the section presented in the trench was as follows:—- Ochreous sand and gravel, overlying white sand, with gravelly patches and ochreous veins4 ft. 9 in.

- Fine gravel, about1 ft. 3 in.

Plate XVI.

- Light grey clay and sand1 ft.

- Irregular bed of coarse gravel in which the implement was found1 ft.

- Light grey clay, mottled brown, containing fresh-water shells (Bithinia)2 ft. 4 in.

Boulder clay.

This trench was sunk at the margin of the deposit, not far from where the beds appear to crop out on the side of the hill, the previous section being about eighty yards distant, and the surface of the ground at that point higher by some feet. It will be observed that the beds of sand, gravel, and clay containing freshwater shells and peaty matter there attain a thickness of about twenty-five feet greater than in the trench, and therefore that they dip in the opposite direction to the slope of the hill. The character of the deposit is evidently fluviatile or lacustrine, and the beds, more especially those of clay, seem to become thicker as we approach the middle of the lake or river. The configuration of the surface of the country when this deposit was formed, must, however, have been widely different from what it is at present, as the high ground surrounding the lake or forming the bank of the river, and from which the successive beds must have been washed down, has, as Mr. Frere long ago observed, now disappeared; for skirting one side of the brick-field, and at the base of the hill on the slope of which the beds of drift crop out, is a valley watered by a small brook, a tributary of the Waveney.

There can be no question that these beds of drift, like those of similar character at Abbeville and Amiens, are entirely undisturbed. At this spot they rest upon the boulder clay of geologists, and are consequently of more recent date, though probably more ancient than the great mass of superficial gravel of the district, by which they in turn seem to be overlaid.

Hoxne is not, however, the only place in England where flint implements have been found under such conditions, for another weapon of the spear-head form has been obligingly pointed out to me in the collection at the British Museum, by Mr. Franks, and is thus described in the Sloane Catalogue:—

"No. 246. A British weapon, found with elephant's tooth, opposite to black Mary's, near Grayes inn lane—Conyers. It is a large black flint, shaped into the figure of a spear's point. K.[19]" This implement is engraved in Plate XVI. and is precisely similar in all its characteristics to some weapons found at Hoxne and Amiens. It is not a little singular that it too should have been found in juxtaposition with a tooth and indeed other remains of an elephant.

It is satisfactory to find these instances of the discovery of flint implements of this class placed on record so long ago, as it places beyond all reasonable doubt the fact of their being really the work of man. They have been exhibited as weapons in our Museums for many years, and their artificial character has never been doubted, nor indeed could it ever have been called in question by an unprejudiced observer.

Other instances have occurred of such implements being found in England, but the exact circumstances of their discovery have still to be investigated from a geological point of view. In Mr. Bateman's[20] Catalogue of the Antiquities in his collection, No. 787 C, of objects found in 1850, is thus entered—"Eight instruments found near Long Low, Wetton, including one very large, and like some figured in the Archæologia, Vol. XIII. p. 204." Mr. Bateman informs me that these were found near the surface, a circumstance which in no way affects the question of their antiquity. In the collection of Mr. Warren of Ixworth are also two specimens of implements of the spear-head type (one of them broken), which were found at Icklingham, Suffolk, in the gravel dug in the valley of the Lark. I have visited the spot where they were found in company with Mr. Prestwich, but owing to the hurried nature of our visit further investigation is necessary before determining this to be a conclusive instance of the implements having been discovered in undisturbed drift. There appears, however, to be nothing in the character of the drift of that district, in which also we found traces of mammalian bones, to militate against such an hypothesis.

In France, similar implements, both of the simple and more elaborate forms, have been discovered by M. Gosse in the gravel-pits of La Motte Piquet near Paris, together with the remains of the mammoth and other animals; and I must not omit to record that this very spot had been pointed out by M. de Perthes, some years ago, as one in which such a discovery was more than probable.

I have no doubt that before many years have elapsed various other instances of the finding of similar implements, under similar circumstances with those from Hoxne and from the valley of the Somme, will have been placed on record, and that the existence of man upon the earth previously to the formation of these drift deposits will be regarded by all as a recognised fact.

Who were the race of men by whom these implements were fashioned, and at what exact period they lived, will probably be always a matter for conjecture. Whether the existence of man upon the earth is to be carried back far beyond the limits of Egyptian or Chinese chronology, or whether the formation of these beds of drift, and the period when the mammoth and rhinoceros, the great cave bear and its tiger-like associate, roamed at large through this country, should be brought down nearer to our own days than has hitherto been supposed, are questions that will not admit of a hasty decision.

It must, however, I think be granted that we have now strong, I may almost say conclusive, evidence of the co-existence of man with these extinct mammalia. The mere fact that the flint implements have been found as component parts of a gravel also containing the bones or teeth of the mammoth or rhinoceros does not of course prove that the men who fashioned them lived at the same period as these animals. Their bones might, under certain circumstances, have been washed out of an older gravel, (as, for instance, by the action of a flooded river,) have then been brought into association with relics of human workmanship, and re-deposited in their company in a re-constructed gravel. But there does not appear to be any probability of this having been the case at Hoxne or in the valley of the Somme. The bones are many of them but little if at all worn, as they would have been under such circumstances; especially as the only alteration in structure that they have undergone is the loss of their gelatine; but, above all, there is the fact that in the lower beds of the sand-pits at Menchecourt, those in which the flint implements have been found, the skeleton of a rhinoceros[21] was discovered nearly entire; which could not possibly have been the case in a re-constructed drift. The bones of the hind leg of a rhinoceros, all in their proper positions, as if the ligaments had still been attached at the time of its becoming imbedded, were found in the same place.

I have already remarked on the possibility of the Menchecourt beds which contained these remains being rather more recent than those at a higher level; but under any circumstances the presence of the nearly perfect frames and limbs of the extinct mammalia in them is a matter of the highest significance in the present inquiry.

But there is another argument in favour of the co-existence of man with these extinct animals which must not be overlooked. If there had been but a single instance of the discovery of the flint implements in conjunction with the bones and teeth of the animals, the assumption that the implements and the mammalian remains were derived from different sources and belonged to two entirely distinct periods, would be difficult of disproof; but when we consider that the instances of such discoveries are already numerous, and have, moreover, taken place in such widely distant localities, that assumption is untenable.

We have at various places round Abbeville the flint implements found associated with the remains of the mammoth, rhinoceros, and other extinct animals; at St. Acheul, near Amiens, we have the like; in the pits of La Motte Piquet they are found with the remains of the mammoth, the Cervus tarandus priscus, the Bos primigenius, and probably the cave-lion; at Hoxne with the mammoth and other remains; and in Gray's Inn Lane with remains of an elephant. This constant association of the two classes of relics affords certainly strong presumptive evidence that the animals to which the bones belonged were living at the same period as the race of intelligent beings who fashioned the weapons of flint.

An argument has been raised against their having co-existed, upon the assumption that human bones have never been discovered in company with those of the extinct quadrupeds. But neither are they recorded to have been found in company with those implements which are acknowledged by nearly all to be of human workmanship.

It appears to me, moreover, very doubtful, in point of fact, whether human bones have not been really found associated with those of the extinct mammalia, more especially in cave-deposits. At all events it is a negative very difficult to prove. But, assuming the fact to be as stated, are there not reasons why it is probable that human remains should be of extremely rare occurrence, if not entirely absent, in such drifts as those of the valley of the Somme and at Hoxne? The mammalian remains found in them are probably mainly those of animals whose dead bodies had been reduced to skeletons, and were lying on the face of the earth before being carried off by the water, whether of an overwhelming cataclysm, or the torrent of a flooded river, and not simply those of animals drowned by its action. Whereas it may safely be assumed that the natural instincts of man would have led them to "bury their dead out of their sight," and thus place them beyond the reach of the currents of water.

It must also be borne in mind that there is no appearance of the drift at any of the places mentioned having been caused by anything like a general submergence of the country, or an universal deluge, as it does not extend over the highest points of ground; so that there is no reason for supposing the waters from which the drift was deposited to have caused any great loss of human life.

It is somewhat curious that we have already instances of the existence of living creatures being proved to demonstration by other evidence than that of their actual remains (for those have never been discovered) in some of the chelonians, saurians, and batrachians of the new red-sandstone and other formations. Footprints of these animals, or ichnolites, are found in abundance, but the bones of the various species which have left these records of themselves "upon the rock for ever" have still to be found. Dr. Hitchcock enumerates no less than fifty-three species from the Jurassic, liassic, or triassic beds of the valley of the Connecticut, of which the existence has been determined by their foot-prints alone.

In the case of the Pfahlbauten lately discovered in the lakes of Switzerland and elsewhere, though implements of all kinds have been found in great abundance, yet human remains are of excessively rare occurrence. It is, however, almost beyond the bounds of probability to suppose that the flint implements from the drift are relics of a race of men who in like manner placed their dwellings upon artificial islands, though in far more remote antiquity than those who constructed the Pfahlbauten.

The question of the contemporaneous existence of man with the mammoth and other animals of the same age is of great importance, as the best if not the only means of fixing some approximate date to these flint implements, though from the nature of all geological evidence, and the possibility of the same results upon the earth's surface being attained in a greater or less period of time according to the greater or less energy of the agent producing them, any estimate of their age will always be liable to objections. But if the co-existence of man with this now extinct fauna be proved, then the basis of induction is enormously extended for arriving at some estimate of the antiquity of man : for the condition and probable age of drift-beds containing the mammalian remains alone, and unassociated with human relics, will then fairly enter as elements into the calculation. It is, however, at present premature to say more upon this point.

I will only add that the presence, in the drift of the valley of the Somme, of the Cyrena consobrina, or trigonula, a bivalve no longer European, though still found in the waters of the Nile, and which is frequently associated with elephant remains in the drift of our valleys, is also of significance in considering the question of the age of these implement-bearing beds.

If we are compelled to leave the mammalian remains out of the question, it seems to me by no means easy, in the present state of our knowledge, to assign even an approximate age to these deposits. Ranging as they do all the way up the slopes of the valley of the Somme near Amiens and Abbeville, there is great difficulty in arriving at any exact conception of the conditions under which they were formed, far more so of the period of their formation. The clays, the sands, and the gravels, all appear to be such as would be formed by the action of a river occasionally in rapid motion, and then again dammed up so as to form as it were a lake, or series of lakes.

But that this could not have been effected in the present configuration of the valley of the Somme, or of the country near Hoxne, is apparent. There must indeed have been a considerable difference in the land-surface at those places, at some former time, for it to have been possible for such deposits to have been formed; but what the configuration was at the time of their formation, and how long a period must have elapsed for it to have become changed into what it is at present, are questions for the geologist rather than the antiquary, and even he would require more facts than are at present at his command to speak with confidence on these points.

Thus much appears to be established beyond a doubt; that in a period of antiquity, remote beyond any of which we have hitherto found traces, this portion of the globe was peopled by man; and that mankind has here witnessed some of those geological changes by which these so-called diluvial beds were deposited. Whether they were the result of some violent rush of waters such as may have taken place when "the fountains of the great deep were broken up, and the windows of heaven were opened," or whether of a more gradual action, similar in character to some of those now in operation along the course of our brooks, streams, and rivers, may be matter of dispute. Under any circumstances this great fact remains indisputable, that at Amiens land which is now one hundred and sixty feet above the sea, and ninety feet above the Somme, has since the existence of man been submerged under fresh water, and an aqueous deposit from twenty to thirty feet in thickness, a portion of which at all events must have subsided from tranquil water, has been formed upon it; and this too has taken place in a country the level of which is now stationary, and the face of which has been but little altered since the days when the Gauls and the Romans constructed their sepulchres in the soil overlying the drift which contains these relics of a far earlier race of men.

How great was the lapse of time that separated the primeval race whose relics are here found fossilized, from the earliest occupants of the country to whom history or tradition can point, I will not stay longer to speculate upon. My present object is to induce those who have an opportunity of examining beds of drift in which mammalian remains have been found, to do so with a view of finding also flint implements in them "shaped by art and man's device."

That instruments so rude should frequently have escaped observation cannot be a matter of surprise, especially when we consider that those educated persons who have been in the habit of examining drift deposits have been more on the alert for organic remains than for relics of human workmanship; while the workmen whose attention these implements may for the moment have attracted have probably thrown them away again as unworthy of further notice. I may mention as an instance of this, that in a pit near Peterborough, where Mr. Prestwich showed one of the Abbeville specimens to the workmen, they assured him that they had frequently found them there, and had regarded them as sling-stones; but none had been retained, nor on visiting the spot have I been able to find any traces of them.

As to the localities in England where mammaliferous drift, of a character likely to contain these worked flints, exists, it would occupy too much time and space to attempt any list of them. Along the banks of the Thames, the eastern coast of England, the coast of western Sussex, the valleys of the Avon, Severn and Ouse, and of many other rivers, in fact in nearly every part of England, have remains of the Elephas primigenius and its contemporaries been found. Almost every one must be acquainted with some such locality: there let him search also for flint implements such as these I have described, and assist in determining the important question of their date. A new field is opened for antiquarian research, and those who work in it will doubtless find their labours amply repaid.

JOHN EVANS.

Nash Mills,

Hemel Hempsted.

- ↑ See especially an article by the late Dr. Mantell in the Archæological Journal, vol. vii. p. 327.

- ↑ Prestwich, "The Ground beneath us," p. 6.

- ↑ Paris, 8vo. vol. i. 1847, (printed in 1844-6,) vol. ii. 1857.

- ↑ See Lyell's Principles of Geology, ed. 1853, pp. 737, 738, &c.

- ↑ Mantell's Petrifactions and their Teachings, 1851, p. 481.

- ↑ Proceedings of Geological Society, June 22, 1859.

- ↑ Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, vol. xvi. p. 104.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Royal Society, May 26, 1859.

- ↑ Ant. Celt. et Antédiluviennes, vol. i. p. 234.

- ↑ Ibid. vol. ii. p. 118.

- ↑ Since the publication of the report of this Paper in the Athenæum, there has been some correspondence in that and other journals upon the question whether these implements were of human or natural origin, which called forth the following expression of opinion from Professor Ramsay, a thoroughly competent judge in such a matter: "For more than twenty years, like others of my craft, I have daily handled stones, whether fashioned by nature or art, and the flint hatchets of Amiens and Abbeville seem to me as clearly works of art as any Sheffield whittle."—(Athæneum, July 16, 1859.)

- ↑ See Wilson's Prehistoric Annals of Scotland, p. 121.

- ↑ Catalogue of the Museum of the Archæological Institute at Edinburgh, in 1856, p. 7.

- ↑ Antiquités Celtiques et Antédiluviennes, vol. i. p. 263.

- ↑ Ibid. vol. ii. p. 430.

- ↑ Ibid. vol. ii. p. 459.

- ↑ See Letter in the Times, Nov. 18, 1859; and Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, vol. xvi. p. 190.

- ↑ Since the reading of this paper, Amiens and Abbeville have been visited by many geologists of note, and, among others, by Sir Charles Lyell, who, in his address to the Geological Section of the British Association, at their meeting in 1859 at Aberdeen, expressed himself as fully prepared to corroborate the observations of Mr. Prestwich. M. Gaudry, and M. Pouchet, of Rouen, on the part of the French Académie des Sciences, and the town of Rouen, have also made researches at Amiens, and have both been successful in discovering specimens of the implements in trenches made under their own personal superintendence.—(Comptes Rendus, tom. 49, No. 18, and Report of M. Pouchet.) See also the Address of Lord Wrottesley to the British Association, at Oxford, in 1860. Some few other facts that have come to my knowledge since this paper was read have been incorporated in the text.

- ↑ This K. signifies that it formed a portion of Kemp's collection; a rude engraving of it illustrates a letter on the antiquities of London by Mr. Bagford dated 1715, printed in Hearne's edition of Leland's Collectanea, vol. i. p. lxiii. From his account it seems to have been found with a skeleton of an elephant in the presence of Mr. Conyers.

- ↑ Bakewell, 1855. p. 59

- ↑ See M. Ravin's Mémoire Géologique sur le Bassin d'Amiens, in the Mémoires de la Société d'Emulation d'Abbeville, 1838, p. 196.