Archaeological Journal/Volume 11/On the Arrangement of Chapels East of Transepts

ON THE ARRANGEMENT OF CHAPELS EAST OF TRANSEPTS.

The ground-plan of religious edifices must in every age be sensibly affected by the nature of the worship to be conducted in them, and, through the ground-plan, the effect becomes hardly less sensible upon the architecture of the building. The primitive basilica, all whose arrangements had reference to a single altar, the great mediæval minster, with its multiplicity of centres of devotion, the thoroughly modern temple with the pulpit as the life and soul of every thing, each expresses the sentiments of its own age, and in each the ritual arrangement directly modifies the architectural character. The first idea produces a long, narrow, and comparatively unbroken structure; the second tends to the erection of a building full of breaks and projections; every possible position is seized upon for the erection of an altar, and where ritual and architecture go thoroughly hand in hand, each altar is marked by a separate chapel, forming a distinct portion of the building. The third ideal, when allowed its full and fair development, is nowhere so consistently carried out as in a semicircular preaching-room. I will not advance further in a direction leading towards the forbidden arena of ritual controversy, but I may make one remark. In adapting ancient ecclesiastical models to modern uses, we should be careful to imitate no feature which is directly and solely connected with some portion of ritual which we do not mean to reproduce. And this I hold to be most distinctly the case with long transepts. I say long transepts, because it is on the length of the transept that the gist of the matter turns.[1]

The cross form of churches Mas doubtless adopted in mediæval times on two very palpable grounds; first, its direct symbolical meaning, this being one of the extremely few cases in which I can bring myself to believe in any symbolism of the kind; secondly, its extreme majesty and variety as an architectural form. Both of these are just as applicable in the nineteenth century as in the twelfth; but another still stronger reason weighed with the mediæval builders, which does not apply to the ritual of the Church of England.

As the use of many altars in the same church became prevalent, the east ends of transepts afforded some of the best positions for the purpose. Next to the high altar itself, and to positions like the east end of a Lady chapel, the altar could nowhere occupy a position of greater dignity. It gained a distinct portion of the church to itself, and the ecclesiastical arrangement might, better than elsewhere, be marked in the architecture of the building. I feel no doubt that whenever transepts projected, as they generally did, beyond the level of the choir aisles, and again, in the numerous cases where no choir aisles existed, they were primarily and essentially, designed as receptacles for altars. The merely symbolical and æsthetical requirements are fully met by transepts not projecting beyond the aisles; St. John's church, at Coventry, is as thoroughly cruciform as if its transepts were as long as the nave. And this church I should recommend to the study of all who wish to apply to modern uses the noblest form which an ecclesiastical building can assume.

At first probably a single altar only was placed in each transept, and to effect the appropriate combination of ritual architecture, an apse was attached to the east face of the transept to receive it. These apses still exist in many great Romanesque churches, both in England and on the continent; and, in our own country at least, it is still more common to find traces of their having existed, than to find them actually standing. In many cases they have been removed in later enlargements of the church; in many they have been destroyed without any such cause, and that, apparently, not always in recent times. Generally of course, we must look for features of this kind only in cathedral or other great churches; in Sussex, however, it struck me as a local peculiarity, that this and other kindred arrangements are applied to buildings of a humbler type than I had been accustomed to find them in elsewhere. It was in fact this circumstance which immediately led me to the present inquiry, and I shall therefore make an especial reference throughout to these Sussex examples.

The best, indeed the only English, example which occurs to me at this moment, of a church with a semicircular apse still remaining attached to the east face of each transept, is to be found in the Abbey church of Romsey. Tewkesbury[2] retains one in the south transept, the northern one being occupied by other buildings. Of instances in Normandy, Mr. Cotman and Mr. Petit supply me with two noble ones, St. Georges Bocherville, and St. Nicholas, at Caen, in the latter of which the apse is remarkable for a high stone roof. Of cases where only vestiges remain of what has been, I may mention the two Metropolitan Cathedrals and that of Chichester, in all of which, Professor Willis has shown that the same arrangement as Romsey existed in the original Norman churches before their enlargement. In Leominster Priory,[3] too, the recent excavations have brought to light the foundations of such an apse attached to the south transept; the northern one has not yet been explored. In fact, the whole arrangement of Leominster, with the apses attached to the transepts, and the apsidal chapels radiating round the presbytery, is identical with that which Professor Willis pointed out as having been the original state of Chichester.

From these instances, where something has been substituted for the apse, we may proceed to another class, in which the apse has been destroyed without any substitute being added, I think whenever we meet with a blocked arch, or the signs of a gable, against the east wall of a Norman transept, Ave may fairly set it down as testifying the previous existence of such an apsidal chapel. Examples occur in Southwell Minster, and in Leonard Stanley Priory, Gloucestershire, and I may add several more from Sussex.

My attention was first drawn to the subject, as regards small churches, by visiting West Ham, one of the two mediæval churches which stand at either end of the Roman fortress at Pevensey, and of which I flatter myself that I carried away as accurate an account as I could, while myself and my sketch-book were deluged by the torrents of rain which accompanied my visit. The first result of this pursuit of knowledge under difficulties was to observe a blocked semicircular arch in the east wall of the south chapel shown in the accompanying ground-plan; another moment revealed the perfect foundations of the apse into which it had led. On the north side, the blocked arch remains, but the foundations do not exist above ground. Still I think we may fairly infer that this side matched the other. The church I conceive to have been originally a Norman cross church, which has lost its character by the addition of a north aisle. The original arrangement would thus be much the same as at Leonard Stanley.

With this example before us, we may, I think, make the same inferences with regard to the churches both of Old and New Shoreham. In the north transept of the former, a Norman arch opens into a chapel of later date, which one can hardly doubt has supplanted an original apse; and, if I mistake not, there are similar indications, though slighter, in the south transept also. At New Shoreham the present magnificent presbytery is unquestionably the successor of a very much smaller one, whose roof-line may still be traced over the eastern arch of the lantern. Two other marks of gables may also be discerned on the eastern sides of the transepts, which clearly mark the position of apses of this kind, destroyed when the present presbytery was erected. It is clear that they are not the traces of anything which could have co-existed with the present aisles.

In these English examples, the eastern limb is always of a certain length, so that the apses attached to the transepts are not brought into any proximity with the extreme east end of the church. But in some of the foreign examples given by Mr. Petit[4] there is no eastern limb, the apse being attached immediately to the tower, so that a building of this sort becomes at once triapsidal. Did the little church of Newhaven, Sussex, possess transepts furnished with apses, it would exactly present the plan of St. Sulpice and the church at Strasburg, engraved by Mr. Petit. Newhaven[5] is, in fact, one of the most remarkable and picturesque buildings with which I am acquainted; it is a church of the Iffley type, with the choir under the tower, the presbytery assuming the form of an apse immediately attached to the eastern wall. It is much to be regretted that the original nave does not exist, but its foundations can be easily traced.

In all the instances which we have hitherto considered, we have had a single altar, and consequently a single apse, in each transept. And this is certainly the arrangement most conducive to architectural effect. But it was often desired to erect several altars in each transept. In this case sometimes two or more small apses were added side by side, as in the eastern transepts at Canterbury; but it seems to have been more common in this case to add what architecturally forms an eastern aisle to the transept, even when there is no western one, as at Peterborough. The bays of these aisles formed chapels, usually screened off from one another, and each contained an altar. This strikes me as an arrangement decidedly inferior to that of the attached apses; the latter proclaim their purpose within and without, while an aisle in no way puts itself forward as a receptacle for altars; indeed we rather expect to find it forming a continuous passage. Numerous examples of this arrangement occur in large churches; I prefer quoting a Sussex example on a very small scale, dating within the period of Transitional Norman. This is at Sompting, a church famous for its Saxon tower, but hardly less worthy of attention on other grounds. The north transept has an eastern aisle of two bays, divided by a pillar, and vaulted; each undoubtedly contained an altar. The transepts at Broadwater, in the same county, had also each of them three chapels attached in a similar manner to the east, which are now unfortunately destroyed. At Sompting, and I imagine at Broadwater, this eastern addition was architecturally a regular aisle in the strictest sense, marked as such in the continuous roofing without, and the continuous arcade within; it was only in the ritual arrangement that they assumed the character of distinct chapels.In a third variety, to be found in all ages, the altars were placed in the transepts themselves, without any projecting apse or aisle. The altars however are, in such cases, often placed under an arch, sometimes, as in St. Cross, pretty much resembling that of a tomb, while in others, as at Irthlingborough, Northamptonshire, it swells into what might have been the approach to a destroyed chapel, only the arch does not go through the wall. This last arrangement is analogous to the false piers and arches sometimes placed against the walls of chancels, as at Cogenhoe, Northampton, and Cuddesden, Oxfordshire. Of this last arrangement the parish church at Battle supplies an excellent instance. On the south side the original blank arcade is perfect; on the north, a later addition has introduced a modification which renders it still more curious.

From these three ways of arranging these altars and chapels, numerous varieties branch forth. As the use of the apse became rare in England, the apses grew into larger and more distinct chapels, with square ends. These often assume a shape not easily to be distinguished from an elongated form of the eastern aisle divided into chapels; while both, again, sometimes approach the character of the ordinary choir-aisles, or chapels, added not to the ends of the transept, but to the sides of the choir. I will bring forward some examples, illustrating my meaning.

Even in Norman times, instead of the apse, we sometimes find a square recess entered by an arch, as may be seen in the south transept at Sompting. There we see every preparation for an altar, within a small quadrangular recess, which one really cannot describe more graphically than as a square apse.

A much larger and more complicated example, of nearly the same transitional date, occurs in St. Mary's, Shrewsbury; but it has been much disturbed by later additions. At C C were small altar-recesses, approached by arches, and forming externally slight projections; at E E chapels, which may be called aisles to a single bay of the choir. But the addition of a large chapel south of the choir, and some smaller additions to the north have greatly obscured the original plan; only, happily, as the great chapel has been added without cutting through the east wall of the transept, half of the arrangement is preserved on each side, and the whole can be recovered.

When the semicircular apse went out of use, it does not seem to have become at all usual to employ the polygonal form in this position. I am not aware of any examples where a polygonal apse occurs possessing anything like the importance of the semicircular ones at Romsey. Smaller ones occur at Patrington, Yorkshire, and in Lincoln Cathedral. The apse much more usually grows into a chapel of considerable size, such as occur at Canterbury, Bristol, and many other large churches. In Chichester Cathedral, too, the apse attached to the north transept has given way to a large quadrangular chapel in the Lancet style. The most singular instance I know is at St. David's.[6] Here the end of each transept is occupied by three arches, forming very nearly a continuous arcade; but of these, the inner pair open from the transepts into the aisles of the presbytery; the central pair contained altars, as at Irthlingborough; while the extreme northern one opens into a large chapel, over which is the chapter-house and other buildings. At Witney, a large chapel equally distinct did occupy a similar position on the south side; but I do not remember if there are there any arrangements for smaller chapels, or altars.

As I before said, these chapels are not always to be accurately distinguished from choir-aisles. At Bristol Cathedral the chapels are still distinctly perceived to be attached to the transept; but those on the north side of Oxford Cathedral might as well be described (in their present state) as additional aisles to the eastern limb. Where churches are less regularly designed, the difficulty is greater. Thus, at Crewkerne, Somerset, the addition E is strictly a north aisle to the choir, though balanced by no southern one; but that at F is of a more ambiguous character. So at Cricklade, Wilts, the chapel on the south side might equally be considered as an appendage either to the choir or to the transept.

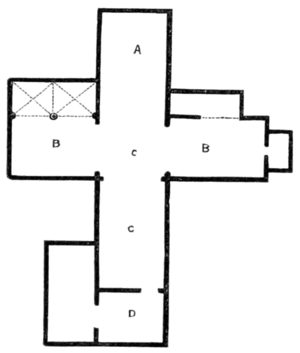

Brecon Priory Church, A Presbytery. B B Transepts, C Tower, D Site of Rood Loft, E Nave. F Site of Cloister.

We also find that the old system of attaching chapels to transepts, and that of forming them in their eastern aisles, often run very much into one another. Thus, at Tintern and Wenlock, the transepts have regular eastern aisles, which form chapels only in a ritual sense. At Buildwas Abbey, Shropshire, or Bayham Abbey, Sussex, this can hardly be said to be the case. The chapels at a a do not form a regular aisle; yet neither do they stand out boldly as distinct chapels. At Bayham, care is taken to mark this, for, though the arches leading into them are quite of the same character as those of a regular arcade—a feature, which, it may be remarked, is nowhere to be found in the church—yet they are carefully divided by a mass of wall with attached responds, instead of a distinct pillar. The whole arrangements of Bayham Abbey are worthy of the most attentive study. The apsidal termination, the transepts thrust east of the choir, the absence of arcades to the latter, and the nave entirely without aisles, form a ground-plan which, as far as my experience goes, is altogether unique.

To my mind, by far the most satisfactory way of treating these appendages, in any style later than Norman, is that followed at Uffington, in Berkshire. The north transept has two, and the south transept one, of these small chapels attached to it, with high gables and stone roofs. These proclaim their purpose as clearly as the old Norman apses, and yield to them only in picturesque effect.

Bayham Abbey Church.

A Presbytery, B B Transepts, C Choir, extending under the Central Tower, D Apparent site of the Rood Loft, E Nave, F Cloister, G Ruined buildings.

In other cases, we sometimes find additions of various kinds to the west of the transept, as in Waltham Abbey, and Wedmore, Somerset; or sometimes the transept itself is made double, as at Oakham: but though these arrangements were, doubtless, prompted by the same desire of obtaining additional sites for altars, they hardly come within the scope of my present subject.

The arrangement of which I have drawn up this slight sketch, is one on which every observer will always be prepared with his own examples, I have thought it better, whenever I could, to draw mine rather from smaller churches than from our great cathedrals. The Sussex examples struck me as especially remarkable, as they exhibit on a small scale, what I had been previously used to only in much larger structures. Features of this kind in a small building immediately strike the visitor; while in a vast minster, unless he is actually going to write its history, the attention is directed to other things, and he may come away without noticing them. In fact, the whole subject of mediæval church arrangement is one on which every inquirer may find something new in almost every church he visits. EDWARD A. FREEMAN.

- ↑ This is well put in the "Ecclesiologist" for August. 1853, p. 295.

- ↑ See "Petit's Tewkesbury," p. 31, where there are some good remarks on the whole subject.

- ↑ See "Archaeological Journal," vol. x., p. 109.

- ↑ "Remarks on Church Architecture," vol. i., p. 76; vol. ii., p.48.

- ↑ See "archaeological Journal," vol. vi., p. 138.

- ↑ I greatly regret having no drawing to illustrate this. A view will be given in the forthcoming fourth part of the "History and Antiquities of St. David's."