Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction/Chapter 5

A most interesting parallel might be drawn between the advance of the sailors over the ocean from Western Europe and the contemporary advance of the Russian Cossacks across the steppes of the Heartland. Yermak, the Cossack, rode over the Ural Mountains into Siberia in 1533, within a dozen years, that is to say, after Magellan's voyage round the world. The parallel might be repeated in regard to our own days. It was an unprecedented thing in the year 1900 that Britain should maintain a quarter of a million men in her war with the Boers at a distance of 6000 miles over the ocean; but it was as remarkable a feat for Russia to place an army of more than a quarter of a million men against the Japanese in Manchuria in 1904 at a distance of 4000 miles by rail. We have been in the habit of thinking that mobility by sea far outran mobility upon the land, and so for a time it did, but it is well to remember that fifty years ago 90 per cent, of the world's shipping was still moved by sails, and that already the first railway had been opened across North America.

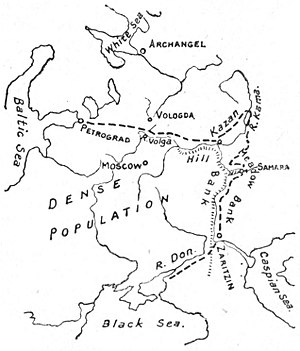

One of the reasons why we commonly fail to appreciate the significance of the policing of the steppes by the Cossacks is that we think vaguely of Russia as extending, with a gradually diminishing density of settlement, from the German and Austrian frontiers for thousands of miles eastward, over all the area coloured on the map with one tint and labelled as one country, as far as Behring Strait. In truth Russia—the real Russia which supplied more than 80 per cent. of the recruits for the Russian armies during the first three years of the War—is a very much smaller fact than the simplicity of the map would seem to indicate. The Russia which is the homeland of the Russian people, hes wholly in Europe, and occupies only about half of what we commonly call Russia in Europe. The land boundaries of Russia in this sense are in many places almost as definite as are the coasts of France or Spain. Trace a line on the map from Petrograd eastward along the Upper Volga to the great bend of the river at Kazan, and thence southward along the Middle Volga to the second great bend at Czaritzin, and finally south-westward along the lower river Don to Rostof and the Sea of Azof. Within this line, to south and west of it, are more than a hundred million Russian people. They, the main stock of Russia, inhabit the plain between the Volga and the Carpathians and between the Baltic and Black Seas, with an average density of perhaps 150 to the square mile, and this continuous sheet of population ends more or less abruptly along the line which has been indicated.

Northward of Petrograd and Kazan is North Russia, a vast sombre forest land with occasional marshes, more than half as large as all the region just defined as the Russian Homeland. North Russia has a population of less than two millions, or not three to the square mile. East of the Volga and Don, as far as the Ural Mountains and the Caspian Sea, lies East Russia, about as large as North Russia, and with a population also of about two millions. But in the Kama Valley, between North and East Russia, is a belt of settled country, extending eastward from Kazan and Samara to the Ural Range, and over that range, past the mines of Ekaterinburg, into Siberia, and right across Western Siberia to Irkutsk, just short of Lake Baikal. This belt of population beyond the Volga numbers perhaps twenty millions. The whole of it, from Kazan and Samara to Irkutsk, in so far as it is occupied by ploughmen and

not by wandering horsemen, is of recent settlement.The Middle Volga, flowing southward from Kazan to Czaritzin, is a remarkable moat not only to Russia but to Europe. The west shore, known as the Hill Bank, in opposition to the Meadow Bank on the other side, is a hill face, some hundred feet high, which overlooks the river for 700 miles; it is the brink of the inhabited plain, here a little raised above the sea level. Stand on the top of this brink, looking eastward across the broad river below you, and you will realise that you have populous Europe at your back, and in front, where the low meadows fade away into the half sterility of the drier steppes eastward, you have the beginning of the vacancies of Central Asia.

A striking practical commentary on these great physical and social contrasts has been supplied in the last few months by the Civil War in Russia. In all North Russia there are but two or three towns larger than a village, and, since the Bolsheviks are based on the town populations, Bolshevism has had little hold north of the Volga. Moreover the sparse rural settlements, chiefly of foresters, have, in their simple, colonial conditions, no grounds for agrarian political feeling, and there is thus no peasant sympathy for the Bolsheviks. As a result, the railway from Archangel to Vologoda on the Upper Dwina long remained open for communication with the ocean and the West. The Transiberian line runs from Petrograd through Vologda, and there is a direct line from Moscow to Vologda which may be considered as leaving Russia proper and entering North Russia at the bridge over the Volga at Jaroslav. For these reasons it was that the Allied Embassies established themselves at Vologda when they retired from Petrograd and Moscow: apart from the convenience of alternative communications with Archangel and Vladivostok, they were outside Bolshevik Russia.

Even more significant was the action of the Czecho-Slovaks on the Moscow branch of the Transiberian line. Advancing from the Ural Mountains, with the support of the Ural Cossacks, they took Samara at the point where the railway reaches the Meadow Bank, and they seized the great bridge over the river at Syzran. They even penetrated a short way along the line to Penza within the real Russia, but through a rather sparsely-populated neighbourhood. Also, they struck up the river to Kazan. In truth they were thus hovering round the edge of the real Russia and threatening it from outside. The British expedition from. Archangel by boat up the Dwina River to Kotlas, and thence by railway to Vyatka on the Transiberian line, appears a less foolhardy enterprise when seen in the light of these realities.

This definition of the real Russia gives a new meaning not only to the Russia but also to the Europe of the nineteenth century. Let us consider that Europe, with the help of the map. All the more northern regions of Scandinavia, Finland, and Russia, and also East Russia southward to the Caucasus, are excluded as being mere vacancies, and with them the Turkish dominion in the Balkan Peninsula. It will be remembered that Kinglake in Eöthen, writing in 1844, considered that he was entering the East when he was ferried across the river Save to Belgrade. The boundary between the Austrian and Turkish Empires as settled by the Treaty of Belgrade in 1739, was not varied until 1878. Thus the real Europe, the Europe of the European peoples, the Europe which, with its overseas Colonies, is Christendom, was a perfectly definite social conception; its landward boundary ran straight from Petrograd to Kazan, and then along a curved line from Kazan by the Volga and Don Rivers to the Black Sea, and by the Turkish frontier to near the head of the Adriatic. At the one end of this Europe is Cape St. Vincent standing out to sea; at the other end is the land cape formed by the Volga elbow at Kazan. Berlin is almost exactly midway between St. Vincent and Kazan. Had Prussia won the

Fig. 28.—The real Europe, East and West, with the addition of Barbary, the Balkans, and Asia Minor (see pp. 159, 160).

Let us now divide our Europe into East and West by a line so drawn from the Adriatic to the North Sea that Venice and the Netherlands may lie to the west, and also that part of Germany which has been German from the beginning of European history, but so that Berlin and Vienna are to the east, for Prussia and Austria are countries which the German has conquered and more or less forcibly Teutonised. On the map thus divided let us 'think through' the history of the last four generations; it will assume a new coherency.

The English Revolution limited the powers of Monarchy, and the French Revolution asserted the rights of the People. Owing to disorder in France, and her invasion from abroad, the organiser Napoleon was thrown up. Napoleon conquered Belgium and Switzerland, surrounded himself with subsidiary kings in Spain, Italy, and Holland, and made an alliance with the subordinate Federation of the Rhine, or, in other words, with the old Germany. Thus Napoleon had united the whole of West Europe, saving only insular Britain. Then he advanced against East Europe, and defeated Austria and Prussia, but did not annex them, though he compelled them to act as his allies when he afterwards went forward against Russia. We often hear of the vast spaces for Russian retreat which lay behind Moscow; but, in fact, Napoleon at Moscow had very nearly marched right across the inhabited Russia of his time.[1] Napoleon was brought down partly by the exhaustion of his French man-power, but mainly because his realm of West Europe was enveloped by British sea-power, for Britain was able to bring to herself supplies from outside Europe and to cut West Europe off from similar supplies. Naturally she allied herself with the Powers of East Europe, but there was only one way by which she could effectively communicate with them, and that was through the Baltic. This explains her naval action twice at Copenhagen. Owing to her command of the sea, Britain was, however, able to land her armies in Holland, Spain, and Italy, and to sap the Napoleonic strength in rear. It is interesting to note that the culminating victory of Trafalgar and the turning-point of Moscow lay very nearly at the two extremes of our real Europe. The Napoleonic War was a duel between West and East Europe, whose areas and populations were about evenly balanced, but the superiority due to the higher civilisation of West Europe was neutralised by British sea-power.

After Waterloo, East Europe was united by the Holy League of the three Powers—Russia, Austria, and Prussia. Each of the three advanced westward a stage, as though drawn by a magnet in that direction. Russia obtained most of Poland, and thus extended a political peninsula into the heart of the physical peninsula of Europe. Austria took the Dalmatian coast, and also Venice and Milan in the mainland of Northern Italy. Prussia obtained a detached territory in the old Germany of the West, which territory was divided into the two provinces of the Rhineland and Westphalia. This annexation of Germans to Prussia proved to be a much more significant thing than the addition of Poles to Russia and of Italians to Austria. The Rhineland is an anciently civilised country, and so far Western that it accepted the Code Napoleon for its law, which it still retains. From the moment that the Prussians thus forced their way into West Europe a struggle became inevitable between the Liberal Rhineland and the Conservative Brandenburg of Berlin. But that struggle was postponed for a time owing to the exhaustion of Europe.British naval power continued the while to envelop West Europe from Heligoland, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Gibraltar, and Malta. By changes precipitated in the years 1830 to 1832 the temporary reaction in the West was brought to an end, and the middle classes came into power in Britain, France, and Belgium. In the years from 1848 to 1850 the democratic movement spread eastward of the Rhine, and Central Europe was ablaze with the ideas of freedom and nationality, but from our point of view two events, and two only, were decisive. In 1849 the Russian Armies advanced into Hungary and put the Magyars back into their subjection to Vienna, thereby enabling the Austrians to reassert their supremacy over the Italians and Bohemians. In 1850 took place that fatal conference at Olmütz when Russia and Austria refused to allow the King of Prussia to accept the All-German Crown which had been offered to him from Frankfurt in the West. Thus the continuing unity of East Europe was asserted, and the Liberal movement from the Rhineland was definitely balked.

In 1860 Bismarck, who had been at Frankfurt, and who had also been Ambassador in Paris and Petrograd, was called to power at Berlin, and resolved to base German unity not on the idealism of Frankfurt and the West, but on the organisation of Berlin and the East. In 1864 and 1866 Berlin overran West Germany, annexing Hanover and thereby opening the way into the Rhineland for Junker militarism. At the same time Berlin weakened her competitor Austria by helping the Magyar to establish the dual government of Austria-Hungary, and by depriving Austria of Venice. France had previously recovered Milan for the West. The War of 1866 between Prussia and Austria was, however, in essence merely a Civil War; this became evident in 1872 when Prussia, having shown that her power was irresistible in the War against France, formed the League of the Three Emperors, and thus reconstituted for a time the East Europe of the Holy Alliance. The centre of power in East Europe was now, however, Prussia, and no longer Russia, and East Europe had established a considerable Rhenish 'Glacis' against West Europe.

For some fifteen years after the Franco-Prussian War Bismarck ruled both East and West Europe. He ruled the West by dividing the three Romance Powers of France, Italy, and Spain. This he accomplished in regard to their relations to Barbary, the 'Island of the West' of the Arabs. France had taken the central portion of Barbary, known as Algeria, and by encouraging her to extend her dominion eastward into Tunis and westward into Morocco, Bismarck brought her interests into conflict with those of Italy and Spain. In East Europe there was a somewhat similar rivalry between Russia and Austria in respect of the Balkan Peninsula, but here the effort of Bismarck was to hold his two allies together. Therefore, after making the Dual Alliance with Austria in 1878, Bismarck negotiated his secret Reinsurance Treaty with Russia. He desired a solid East Europe under Prussian control, but a divided West Europe.

The events which we have thus briefly called to mind are no mere past and dead history. They show the fundamental opposition between East and West Europe, an opposition which becomes of world-significance when we remember that the line through Germany which History indicates as the frontier between East and West is the very line which we have on other grounds taken as demarking the Heartland in the strategical sense from the Coastland.

In West Europe there are two principal elements, the Romance and the Teutonic. As far as the two chief nations, Britain and France, are concerned, there is and can be in modern times no question of conquest of the one by the other. The Channel lies between them. Away back in the Middle Ages it is true that for three centuries French Knights ruled England, and that for another century the English tried to rule France. But those relations ended for good when Queen Mary lost Calais. The great wars between the two countries in the eighteenth century were waged primarily to prevent the French Monarchy from dominating the Continent of Europe. For the rest, they were wars of colonial and commercial rivalry. So far, also, as the Teutonic element along the Rhine is concerned, there was certainly in the past no very deep-seated hostility to the French. The Alsatians, though German by speech, became—it is one of the great facts of history operative to this day—French in heart. Even what is now the Rhine province of Prussia accepted, as we have seen, the Code Napoleon.

In East Europe there are also two principal elements, the Teutonic and the Slavonic, but no equilibrium has been established between them as between the Romance and Teutonic elements of West Europe. The key to the whole situation in East Europe—and it is a fact which cannot be too clearly laid to heart at the present moment—is the German claim to dominance over the Slav. Vienna and Berlin, just beyond the boundary of West Europe, stand already within territory that was Slav in the earlier Middle Ages; they represent the first step of the German out of his native country as a conqueror eastward. In the time of Charlemagne the rivers Saale and Elbe divided the Slavs from the Germans, and to this day, only a short distance south of Berlin, is the Circle of Kottbus, where the peasantry still speak Wendish, or the Slav tongue of all the region a few centuries ago. Outside this little Wendish remnant, the Slav peasantry have accepted the language of the German Barons who rule them in their large estates. In South Germany, where the peasantry is truly German, the land is held by small proprietors.

No doubt there is a difference of impression made on foreigners by the Austrian's and by the Prussians of noble birth; that difference comes, no doubt, from the fact that the Austrians advanced eastward from South German homes, whereas the Prussians came from the harsher North. But in Prussia and Austria alike, the great landowners were autocrats before the War, though we commonly think of the Junker as Prussian only. The peasantry of both countries was in a state of serfdom until a comparatively short time ago.

Fig. 29.—The surviving islands of Wendish (Slavonic) speech at Kottbus, encircled by the flowing tide of German speech.

The two long limbs of territory thrust out by Prussia in north-easterly and south-easterly directions have a deep historical meaning for those who read history on the map, and it is history on the map which constitutes one of the great realities with which we must deal in our Reconstruction. The map showing the distribution of languages tells in this instance even, more than the political map, for it shows three tongues of German speech and not merely two. The first lies north-eastward along the Baltic Shore; it represents a German conquest and forced Teutonisation of the later Middle Ages. By the coastwise water-way the Hanseatic Merchants of Lübeck and the Teutonic Knights, no longer occupied in Crusading, conquered all the shorelands to where now stands Petrograd. By subsequent history half of this strip of 'Deutschthum' was incorporated with the Berlin Monarchy, and the other half became the Baltic Provinces of the Russian Czardom. But the Baltic Provinces retained, to our days, their German merchant community of Riga, their German University of Dorpat, and their German Barons as landlords. Under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk the German element was again to have ruled in these lands of Courland and Livonia.

The second pathway of the Germans was up the Oder River to its source in the Moravian Gate, the deep valley leading from Poland towards Vienna between the mountains of Bohemia on the one hand, and the Carpathian Mountains on the other hand. The German

Fig. 30—Showing the three eastward tongues of German speech, and the scattered German settlements as far as the Volga.

(1) Prussia. (2) Silesia. (3) Austria.

The third eastward path of the Germans was down the Danube, and by southward passes also into the Eastern Alps. This has become the Austrian Archduchy about Vienna, and the Carinthian Duchy—German-speaking—in the Austrian Alps. Between the Silesian and Austrian Germans projects westward the province of Bohemia, mainly of Slav speech. Let us not forget that Posen and Bohemia have retained their native tongues, and that the three salients of German speech represent three streams of conquest.

Beyond even the utmost points of these three principal invasions of Deutschthum, there are many scattered German colonies of farmers and miners, some of them of very recent origin. They occur at many points in Hungary, although for political purposes the Germans have there now very much identified themselves with the Magyar tyranny. The Saxons in Transylvania share with the Magyars of that region a privileged position amid a subject population of Rumanian peasants.[2] In Russia a chain of German settlements lies eastward through the north of the Ukraine almost to Kieff. Only on the Middle Volga, about the city of Saratof, do we come to the last patch of these German colonists

We must not, however, think of German influence among the Slavs as being limited to these extensions of the German tongue, though they are a very powerful factor—since German Kultur has gone wherever the German language has given it entry. The Slav kingdom of Bohemia was completely incorporated into the German Imperial System; the King of Bohemia was one of the Electors of the Emperor under the constitution which came to an end only in 1806, after the battle of Austerlitz. The Poles, the Czechs, the South Slavs of Croatia, and the Magyars are Roman Catholic—that is to say, of the Latin or Western branch of the Church, and this has certainly meant an extension of German influence as against the Greek Church of the Russians. After the siege of Vienna in 1683, the Austrian Germans advanced step by step in the eighteenth century, driving the Turks before them from Hungary, until by the Treaty of Belgrade in 1739 they fixed the line which, for more than a hundred years, afterwards delimited Turkish power towards Christendom. Undoubtedly the Austrians thus rendered a great service to Europe, but the incidental effect, so far as the Croatians, Magyars, Slovaks, and Rumanians of Transylvania were concerned, was merely to substitute the mastery of the German for that of the Turk. When Peter the Great of Russia moved his capital at the beginning of the eighteenth century from Moscow to Petrograd, he went from a Slavonic to a German environment, a fact recorded in the German name St. Petersburg. As a consequence, throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, German influence was great in Russian Government. The Russian bureaucracy, on which the Czardom depended, was, in large measure, recruited from among the cadets of the German baronial families of the Baltic provinces.

Thus East Europe has not consisted, like West Europe, of a group of peoples independent of one another, and—until Alsace was taken by Prussia—without serious frontier questions between them; East Europe has been a great triple organisation of German domination over a mainly Slavonic population, though the extent of the German power, no doubt, varied in different parts. In this fact we have the key to the meaning of the volte-face of 1895, when was concluded the incongruous Franco-Russian alliance between Democracy and Despotism. When Russia allied herself with France against the Germans, much more was implied than merely a reshuffling of the cards on the play-table of Europe. Something fundamental had happened in East Europe from the point of view of Berlin. Prior to that great and significant event there had been long bickerings between the Russian and Austrian Governments as the result of their rivalry in the Balkans, but these were in the nature of family quarrels, no less than was the short war between Prussia and Austria in 1866. When Russia advanced to the Danube against Turkey in 1853 and Austria massed forces to threaten her from the Carpathians, the friendship of the Holy Alliance, which had subsisted since 1815, was, no doubt, suspended until Bismarck brought the three despotisms together again in his Three-Kaiser Alliance of 1872. But it so happened that, during the interval, Russia was not in a position to advance afresh against the Turks, owing to the losses which she had experienced in the Crimean War, and therefore no irremediable breach ensued between her and Austria. But the Three-Kaiser Alliance could not last long after Austria had given notice of her Balkan ambitions by occupying the Slav Provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878. Some uncomfortable years followed, during which German strength was mounting up, before Russia was convinced that the alternative before her was either an alliance with the French Republicans or the acceptance of a position of subordination to Germany like that to which Austria had been reduced.

So much in regard to the history of West and East Europe during the Victorian Age. There was, however, a contemporary history of the Not-Europe which we must now bring into our reckoning. The Naval warfare which culminated in the battle of Trafalgar had the effect of dividing the stream of the world's history into two separate currents for nearly a century. Britain enveloped Europe with her sea-power, but save in so far as it was necessary at times for her to intervene around the Eastern Mediterranean because of her stake in the Indies, she took no serious part in the politics of the European Peninsula. British sea-power, however, also enveloped the great world promontory which ends in the Cape of Good Hope, and, operating from the sea-front of the Indies, came into rivalry with the Russian-Cossack Power, then gradually completing its hold on the Heartland. In the far north the Russians descended the great Amur River to the Pacific Coast before the Crimean War. It is usual to attribute the opening of Japan to the action of the American Commodore Perry in 1853, but the presence of the Russians in the island of Sakhalin, and even as far south as Hakodate in Yesso, had done something to prepare the way. In regard to Britain, the most immediate Russian menace was, of course, beyond the North-West Frontier of India.

In the nineteenth century Britain did what she liked upon the Ocean, for the United States were not yet powerful, and Europe was fully occupied with its wars. Shipping and markets were the objective of the Nation of Shopkeepers under the régime of the Manchester School of political thought. The principal new markets offering were among the vast populations of the Indies, for Africa was unexplored, and for the most part went naked, and the Americas were not yet populous. Therefore, while Britain might have annexed almost every coast outside Europe except the Atlantic coast of the United States, she limited herself to calling ports for her shipping on the ocean road to the Indies, and to such colonial developments in unoccupied regions as were forced on her by her own adventurers, whom she tried in vain to check. But she was compelled to make a steady advance in India, of that kind which old Rome had known so well, when one new province after another was annexed for the purpose of depriving invaders of their bases against the territory already possessed.

The map reveals at once the essential strategic aspects of the rivalry between Russia and Britain during the nineteenth century. Russia, in command of nearly the whole of the Heartland, was knocking at the landward gates of the Indies. Britain, on the other hand, was knocking at the sea gates of China, and advancing inland from the sea gates of India to meet the menace from the north-west. Russian rule in the Heartland was based on her man-power in East Europe, and was carried to the gates of the Indies by the mobility of the Cossack cavalry. British power along the sea frontage of the Indies was based on the man-power of the distant islands in West Europe, and was made available in the East by the mobility of British ships. Obviously there were two critical points in the alternative voyages round from West to East; those points we know to-day as the 'Cape' and the 'Canal.' The Cape lay far removed from all overland threat throughout the nineteenth century; practically South Africa was an island. The Canal was not opened until 1869, but its construction was an event which cast its shadow before. It was the Frenchman, Napoleon, who gave to Egypt, and therefore also to Palestine, its modern importance, just as it was the Frenchman Dupleix, who, in the eighteenth century, showed that it was possible to build an empire in India from the coast inward, on the ruins of the Mogul Empire which had been built from Delhi outward. Both ideas, that of Napoleon and that of Dupleix, were essentially ideas of sea-power, and sprang not unnaturally from France in the Peninsula of West Europe. By his expedition to Egypt Napoleon drew the British Fleet to the battle of the Nile in the Mediterranean, and also drew the British Army from India, for the first time, overseas to the Nile Valley. When, therefore, Russian power in the Heartland increased, the eyes both of Britain and France were necessarily directed towards Suez, those of Britain for obvious practical reasons, and those of France partly for the sentimental reason of the great Napoleonic tradition, but also because the freedom of the Mediterranean was essential to her comfort in the Western Peninsula.

But Russian land-power did not reach, in the eyes of people of that time, as far as to threaten Arabia. The natural European exit from the Heartland was by the sea-way through the Straits of Constantinople. We have seen how Rome drew her frontier through the Black Sea, and made Constantinople a local base of her Mediterranean sea-power against the Scythians of the steppes. Russia, under Czar Nicholas, sought to invert this policy, and, by commanding the Black Sea and its southward exit, aimed at extending her land-power to the Dardanelles. The effect was inevitably to unite West Europe against her. So it happened that when Russian intrigue had involved Britain in the First Afghan War in 1839, Britain could not view with equanimity the encampment of a Russian Army on the Bosporus in order to defend the Sultan from the attack, through Syria, of Mehemet Ali, the insurgent Khedive of Egypt. Therefore Britain and France dealt with Mehemet themselves, by attacking him in Syria in 1840.

In 1854 Britain and France were again involved in action against Russia. France had assumed the protectorate of the Christians in the Near East, and her prestige in that respect was being damaged by Russian intrigue in regard to the Holy Places at Jerusalem. So France and Britain found themselves involved in support of the Turks when the Russian armies came against them on the Danube. Lord Salisbury, shortly before his death, declared that in supporting Turkey we had backed the wrong horse. Is that so certain in regard to the middle of last century? Time is of the essence of International Policy; there is an opportunism which is the tact of politics. In regard to things which are not fundamental, is it not recognised that in ordinary social intercourse it is possible to say the right thing at the wrong time? In 1854 it was Russian power, and not yet German power, which was the centre of organisation in East Europe, and Russia was pressing through the Heartland against the Indies, and by the Straits of Constantinople was seeking to issue from the Heartland into the west, and Prussia was supporting Russia.

In 1876 Turkey was again in trouble and was again backed by Britain, though necessarily without the support of France. The result was to head off Russian power from Constantinople, but at the cost of giving to the Germans their first step towards the Balkan Corridor by handing over to Austrian keeping the Slav Provinces, hitherto Turkish, of Bosnia and Herzegovina. On that occasion the British Fleet, by Turkish sufferance, steamed through the Dardanelles to within sight of the minarets of Constantinople. The great change in the orientation of Russian policy had not yet occurred, and neither Russia nor Britain yet foresaw the economic methods of amassing man-power to which Berlin was about to resort.

When we look back on the course of events during the hundred years after the French Revolution, and consider East Europe as the basis of what was on the whole a single force in the world's affairs, do we not realise that separate as people of the Victorian Age often thought the politics of Europe from those of the Not-Europe outside, there was, in fact, no such separation. East Europe was in command of the Heartland, and was opposed by the sea-power of Britain round more than three quarters of the margin of the Heartland, from China through India to Constantinople. France and Britain were commonly allied in action in regard to Constantinople. When, in 1840, there was danger of war in Europe because of the quarrel between the Khedive and the Sultan, instinctively all eyes were turned to the Rhine, where Prussia had established her outpost provinces. Then it was that the German song, the "Wacht am Rhein," was written! But the war threatened against France was not in respect of Alsace and Lorraine, but in support of Russia; in other words, the quarrel was between East and West Europe.

In 1870 Britain did not support France against Prussia. With the after wisdom of events should we not, perhaps, be justified in asking whether we did not in this instance fail to back the right horse? But the eyes of the islanders were still blinded by the victory of Trafalgar. They knew what it was to enjoy sea-power, the freedom of the ocean, but they forgot that sea-power is, in large measure, dependent on the productivity of the bases on which it rests, and that East Europe and the Heartland would make a mighty sea-base. In the Bismarckian period, moreover, when the centre of gravity in East Europe was being shifted from Petrograd to Berlin, it was perhaps not unatural that contemporaries should fail to realise the subordinate character of the quarrels between the three autocracies, and the fundamental character of the war between Prussia and France.

The recent Great War arose in Europe from the revolt of the Slavs against the Germans. The events which led up to it began with the Austrian occupation of the Slav provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878, and the alliance of Russia with France in 1895. The Entente of 1904 between Britain and France was not an event of the same significance; our two countries had cooperated more often than not in the nineteenth century, but France had been the quicker to perceive that Berlin had supplanted Petrograd as the centre of danger in East Europe, and our two policies had, in consequence, been shaped from different angles for a few years. West Europe, both insular and peninsular, must necessarily be opposed to whatever Power attempts to organise the resources of East Europe and the Heartland. Viewed in the light of that conception, both British and French policy for a hundred years past takes on a large consistency. We were opposed to the half-German Russian Czardom because Russia was the dominating, threatening force both in East Europe and the Heartland for half a century. We were opposed to the wholly German Kaiserdom, because Germany took the lead in East Europe from the Czardom, and would then have crushed the revolting Slavs, and dominated East Europe and the Heartland. German Kultur, and all that it means in the way of organisation, would have made that German domination a chastisement of scorpions as compared with the whips of Russia.

Thus far we have been thinking of the rivalry of Empires from the point of view of strategical opportunities, and we have come to the conclusion that the World-Island and the Heartland are the final Geographical Realities in regard to sea-power and land-power, and that East Europe is essentially a part of the Heartland. But there remains to be considered the Economic Reality of man-power. We have seen that the question of base, not only secure but also productive, is vital to sea-power; the productive base is needed for the support of men not only for the manning of ships, but for all the land services in connection with shipping, a fact to-day more clearly realised in Britain than ever before. In regard to land-power we have seen that the camel-men and horsemen of past history failed to maintain lasting empires from lack of adequate man-power, and that Russia was the first tenant of the Heartland with a really menacing man-power.

But man-power does not imply a counting only of heads, though, other things being equal, numbers are decisive. Nor does it depend merely on the number of efficient human beings, though health and skill are of the first importance. Man-power—the power of men—is also, and in these modern days very greatly, dependent on organisation, or, in other words, on the 'Going Concern,' the social organism. German Kultur, the 'ways and means' philosophy, has been dangerous to the outer world because it recognises both Realities, Geographical and Economic, and thinks only in terms of them.

The 'Political' Economy of Britain and the 'National' Economy of Germany have come from the same fountain, the book of Adam Smith. Both accept as their bases the division of labor and competition to fix the prices at which the products of labour shall be exchanged. Both, therefore, can claim to be in harmony with the dominant tendency of thought in the nineteenth century as expressed by Darwin. They differ only in the unit of competition. In Political Economy that unit is the individual or firm; in National Economy it tends to become the State among States. This was the fact appreciated by List, the founder of German National Economy, under whose impulse the Prussian Zollverein or Customs Union was broadened until it included most of Germany. The British Political Economists welcomed the Zollverein, regarding it as an instalment of their own Free Trade. In truth, by removing competition in greater or less degree to the outside, National Economy aimed at substituting for the competition of mere men that of great national organisations. In a word, the National Economists thought dynamically, but the Political Economists in the main statically.

This contrast of thinking between Kultur and Democracy was not at first of great practical significance. In the fifties and sixties of last century the Germans were at their wars. The British Manufacturer was top dog, and, as Bismarck once said. Free Trade is the policy of the strong. It was not until 1878, the date of the first scientific tariff, that the economic sword of Germany was unsheathed. That date marks approximately a very great change in the arts of transport to which due weight is not always attached. It was then that British-built railways in America and British steel-built ships on the Atlantic began to carry bulk-cargoes.

What this new fact of the carriage of bulk—wheat, coal, iron ore, petroleum—means will be realised if we reflect that in Western Canada to-day a community of a million people raise the cereal food of twenty millions, and that the other nineteen millions are at a distance—in Eastern Canada, the Eastern United States, and Europe. Prior to 1878 relatively light cargoes of such commodities as cotton, timber, and coal had been transported over the ocean by sailing ship, but the whole bulk of the cargoes of the world was insignificant as measured by the standards of to-day. Germany grasped the idea that under the new conditions it was possible to grow man-power where you would, on imported food and raw material, and therefore in Germany itself, for strategical use.

Up to this time the Germans, like the British, had freely emigrated, but the German no less than the British populations in the new countries made an increased demand for British manufactures. So the British people grew in number at home as well as in the Colonies and the United States. Cobden and Bright had foreseen this; they meant to have cheap food and cheap raw materials wherewith to make cheap exports. But the rest of the world looked upon our Free Trade as a method of Empire rather than of Freedom; the reverse of the medal was presented to them; they were to be hewers and drawers for Great Britain. The British Islanders unfortunately made the mistake of attributing their prosperity mainly to their free imports, whereas it was chiefly due to their great 'Going Concern,' and the fact that it had been set going before it had competitors. It was because they were 'the strong' in 1846, that they could adopt Free Trade with immediate advantage and without serious immediate disadvantage.

From 1878 Germany began to build up her man-power by stimulating employment at home. One of her methods was the scientific tariff, a sieve through which imports were 'screened,' so that they should contain a minimum of labour and especially of skilled labour. But every other means was resorted to for the purpose of raising a Going Concern which should yield a great production at home. The Railways were bought by the State, and preferential rates granted. The Banks were brought under the control of the State by a system of interlocked shareholding, and credit was organised for industry. Cartels and Combines reduced the cost of production and distribution. The result was that about the year 1900 German emigration, which had been steadily falling, ceased altogether, except in so far as balanced by immigration.

The economic offensive was increased by methods of penetration abroad. Shipping lines were subsidised, and banks were used as trade outposts in foreign cities. International Combines were organised under German control, very largely with the help of the Jews of Frankfurt. Finally, in 1905, Germany imposed such a system of commercial treaties on seven adjoining nations as meant their economic subjection. One of these nations was Russia, then weak from war and revolution. Those treaties are said to have taken ten years to think out—a characteristic efflorescence of Kultur!

The rapid German growth was a triumph of organisation, or, in other words, of the strategical, the 'ways and means' mentality. The fundamental scientific ideas were, most of them, imported, and the vaunted German Technical Education was merely a form of organisation. The whole system was based on a clear understanding of the Reality of the Going Concern—Organised Man-power.

But the Going Concern is a relentless fact, for the first political attribute of the animal Man is hunger. In the ten years before the War Germany was growing at the rate of a million souls a year—the difference between deaths and births. That meant that the productive Going Concern must not only be maintained, but that its 'going' must be constantly accelerated. In the course of forty years the hunger of Germany for markets had become one of the most terrible realities of the world. The fact that the commercial treaty with Russia would come up for renewal in 1916 was probably not unconnected with the forcing of the War; Germany required, at all costs, a subject Slavdom to grow food for her and to buy her wares.

The men who, at Berlin, pulled the lever in 1914, and set free the dammed-up flood of German man-power, have a responsibility which has been analysed and fixed, so far as our information yet goes, with keen research by the unfortunate generation which has had to fight the fearful duel. But before History their guilt will be shared by those who, in years past, set the Concern Going. In this matter British Statesmen and the British People will not be held wholly blameless.

It is the theory of Free Trade that the different parts of the world should develop on the basis of their natural facilities, and that different communities should specialise and render service to one another by exchanging their products freely. It was firmly believed that Free Trade thus made for peace and the brotherhood of men. That may have been a tenable theme in the time of Adam Smith and for a generation or two afterwards. But under modern conditions the Going Concern, or, in other words, accumulating Financial and Industrial strength, is capable of out-weighing most natural facilities. The Going Concern of the Lancashire Cotton Industry is an instance of this on a great scale. A very small difference of price in cheap lines of export will hold or lose a market, and the great Going Concern can best afford to cut prices. Hence Lancashire has maintained her cotton industry for a century against all competitors, though the sources of the raw material and the principal markets for the finished goods are in distant parts of the world. Coal and a moist climate are her only natural facilities, and they can be paralleled elsewhere. The Lancashire cotton industry continues by virtue of momentum.

The result, however, of all specialisation is to make growth lop-sided. When the stress began after 1878, British agriculture waned, though British industry continued to grow. But presently lop-sidedness developed even within British industry; the cotton and ship-building branches still grew, but the chemical and electrical branches did not increase proportionately. It was not only that German penetration designedly robbed us of our Key industries, for the ordinary operation of specialisation in a world which was becoming industrially active outside Britain was bound to produce some such contrasts. Britain developed vastly those industries into which she gradually concentrated her efforts. Therefore she, no less than Germany, became 'market-hungry,' for nothing smaller than the whole world was market enough for her in her own special lines.

Britain had no tariff available as a basis for bargaining; in that respect she stood naked before the world. Therefore, when threatened in some vital market, she could but return threats of sea-power. Cobden probably foresaw this in his later days when he declared the need for a strong British Navy, but the rank and file of the Manchester School were so persuaded that Free Trade made for peace that they gave little thought to the special industrial requirements of sea-power; in their view any trade was equally good provided it were profitable. Yet Britain was fighting for her South American markets when her fleet maintained the Monroe doctrine against Germany in the Manila Incident, and for her Indian market when her fleet kept Germany at bay during the South African War, and for the open door to her China market when her fleet supported Japan in the Russian War. Did Lancashire realise that it was by force that the free import of cottons was imposed on India? Undoubtedly India has profited vastly on a balance by the British Raj, and no great weight of guilt need rest on the Lancashire conscience in this matter; but the fact remains that repeatedly, both within and without the Empire, free-trading, peace-loving Lancashire has been supported by the force of the Empire. Germany took note of the fact and built her fleet, and that fleet in being, and still in being to the end of the War, neutralised a mighty British effort which would have been available otherwise in support of our army in France.The momentum of the Going Concern is very difficult to change in a democracy. The one hope of the future is that, as a result of the lesson of this War, even democracy may learn to take longer views In an economically lop-sided community the majority is on the over-developed side, and it is the majority which chooses the rulers in a democracy. The vested interests as a consequence tend to vest ever deeper, both the interest of labour in earning and buying in particular ways, and of capital in making profit in those same ways; on the average there is nothing to choose between labour and capital in these regards; they both take short views.

But there is the same difficulty of changing the Going Concern in an autocracy, although that difficulty is felt in a different way. The majority in a democracy will not change its economic routine, but autocracy often does not dare to do so. Germany under the Kaiserdom aimed at a World Empire, and to achieve it resorted to appropriate economic expedients for building up her man-power; presently she dared not change her only too successful policy even when it was forcing her to war, for the alternative was revolution. Like Frankenstein she had constructed an unmanageable monster.In my belief, both Free Trade of the laissez-faire type and Protection of the predatory type are policies of Empire, and both make for War. The British and the Germans took seats in express trains on the same line, but in opposite directions. Probably from about 1908 a collision was inevitable; there comes a moment when the brakes have no longer time to act. The difference in British and German responsibility may perhaps be stated thus: the British driver started first, and ran carelessly, neglecting the signals, whereas the German driver deliberately strengthened and armoured his train to stand the shock, put it on the wrong line, and at the last moment opened his throttle valves.

The Going Concern is, in these days, the great Economic Reality; it was used criminally by the Germans, and blindly by the British. The Bolsheviks must have forgotten that it existed.