BERLIN

BERLIN

BERLIN

I AM back again, back again in New York. My rooms are littered with battered bags and down-at-the-heel walking sticks and still-damp steamer rugs, lying where they dropped from the hands of maudlin bellboys. My trunks are creaking their way down the hall, urged on by a perspiring, muttering porter. The windows, still locked and gone blue-grey with the August heat, rattle to the echo of the "L" trains a block away, trains rankling up to Harlem with a sweating, struggling people, the people of the Republic, their day's grind over, jamming their one way to a thousand flat houses, there to await, in an all unconscious poverty, the sunrise of still such another day. The last crack of a triphammer, peckering at a giant pile of iron down the block, dies out on the dead air. A taxicab, rrrrr-ing in the street below, grunts its horn. A newsboy, in neuralgic yowl, bawls out a sporting extra. Another "L" train and the panes rattle again. A momentary quiet ... and from somewhere in a nearby street I hear a grind-organ. What is the tune it is playing? I've heard it, I know—somewhere; but—no, I can't remember. I try—I try to follow the air—but no use. And then, presently, one of the notes whispers into my puckering lips a single word—"Mariechen." Then other notes whisper others—"du süsses Viehchen"; and then others still others—"du bist mein alles, bist mein Traum." And the battered bags and the down-at-the-heel walking sticks and the still-damp steamer rugs and the trunks creaking down the hallway and the rattle of the "L" trains fade out of my eyes and ears and again dear little Hulda is with me under the Linden trees—poor dear little Hulda who ever in the years to come shall bring back to me the starlit romance of youth—and again I feel her so soft hand in mine and again I hear her whisper the auf wiederseh'n that was to be our last good-bye—and I am three thousand miles over the seas. For it's night for me again in Berlin—kronprinzessin of the cities of the world.

I am again on the hitherward shore of the Hundekehlensee, flashing back its diamond smiles at the setting sun. I am sitting again near the water's edge in the moist shade of the Grunewald, and the trees sing for me the poetry that they once sang to the palette of Leistikow. My nose cools itself in the recesses of a translucent schoppen of Johannisberger, proud beverage in whose every topaz drop lies imprisoned the kiss of a peasant girl of Prussia. From the southward side of the Grunewaldsee the horn of a distant hunting lodge seems to call a welcome to the timid stars; and then I seem to hear another—or is it just an echo?—from somewhere out the spur of the Havelberge beyond. Or is just the Johannesberger, soul of the most imaginative grape in Christendom? Or—woe is me—am I really back again across the seas in New York, and is what I hear only the horn of the taxicab, rrrrr-ing in the street below?

But I open my too-dreaming eyes—and yes; I am in the Grunewald. And the summer sun is saffron in the waters of the lake. And about me, at a thousand tables under the Grunewald trees, are a thousand people and more, the people of the Kaiserland, their day's work over, clinking a thousand wohlseins in a great twilight peace and awaiting, in all unconscious opulence, the sunrise of yet such another day. And a great band, swung into the measures by a firm-bellied kapellmeister as gorgeous in his pounds of gold braid as a peafowl, sets sail into "Parsifal" against a spray of salivary brass. And the air about me is full of "Kellner!" and "Zwei Seidel, bitte!" and "Wiener Roastbraten und Stangenspargel mit geschlagener Butter!" and "Zwei Seidel, bitte!" and "Junge Kohlrabi mit gebratenen Sardellenklopsen!" and "Zwei Seidel, bitte!" and "Sahnenfilets mit Schwenkkartoffeln!" and "Zwei Seidel, bitte!" and a thousand schmeckt's guts and a thousand prosits and "Zwei Seidel, bitte!" And no outrage upon the ear is in all this guttural B minor, no rape of exotic tympani, but a sense rather of superb languor and wholesome tranquillity, of harmonious stomachic socialism, an orchestration of honest ovens and a diapason of honest bräus and brunners, with their balmy wealth of nostril arpeggios and roulades.

And thus the evening breeze, come hither through the reeds and cypress from over the purpling Havel hills beyond, takes on an added perfume, an added bouquet, as it transports itself to the sniffer over to the hurrying krebs-suppen and thick brown-gravied platters and dewy seidels. My nose, in its day, has engaged with many a seductive aroma. It has met, at Cassis on the Mediterranean, the fumes breathed by bécasse sur canapés and Château Lafitte '69—and it has ffd and ffd again and again in an ecstasy of inhalation. It has encountered in Moscow, the regal vapours of nevop astowka Dernidoff sweeping across a slender goblet of golden sherry—and it has been abashed at the delirium of scent. On the Grand Boulevards, it has skirmished with punch à la Toscane flavoured with Maraschino and with bitter almonds—and has inhaled as if in a dream. The juicy, dripping cuts of Simpson's in London, the paradisian pudding sueldoiro on the little screened veranda in the shadow of the six-minareted Mosque of El-Azhar in Cairo, the salmon dipped in Chambertin and the artichokes, sauce Barigoule, at Schönbrunn on the road to Vienna, the escaloppes de foie gras à la russe (favourite dish of the late Beau McAllister) at Delmonico's at home—all these and more have wooed my nostril with their rare fragrances. But, though I have attended many a table and given audience to many an attendant perfume, nowhere, nor never, has there been borne in upon me the like of that exquisite nasal blend of bratens and bräus with which the twilight breezes have christened me among the trees of the Grunewald. Forgotten, there, are the roses on the moonlit garden wall in Barbizon, chaperoned by the fairy forest of Fontainebleau; forgotten the damp wild clover fields of the Indiana of my boyhood. All vanished, gone, before the olfactory transports of this concert of hops and schnitzels, of Rhineland vineyards and upland käse. And here it is, here in the great German out-of-doors, on the border of the Hundekehlen lake, with a nimble kellner at my elbow, with the plain, homely German people to the right and left of me, with the stars beginning to silver in the silent water, with the band lifting me, a drab and absurd American, into the spirit of this kaiserwelt, and with the innocent eyes of the fair fräulein under yonder tree intermittently englishing their coquettish glances from the eisschokolade that should alone engage them—here it is that I like best to bide the climbing of the moon into the skies over Berlin—here it is that I like best to wait upon the city's night.

Ah, Berlin, how little the world knows you—you and your children! It sees you fat of figure, an Adam's apple struggling with your every vowel, ponderous of temperament. It sees you a sullen and varicose mistress, whose draperies hang heavy and ludicrous from a pudgy form. It sees you a portly, pursy, foolish Undine struggling awkwardly from out a cyclopean vat of beer. It hears your music in the ta-tata-tata-ta-ta of your "Ach, du lieber Augustin" alone; the sum of your sentiment in your "Ich weiss nicht was soll es bedeuten." Wise American journalists, commissioned to explore your soul, have returned characteristically to announce that you "In your German way" (American synonyms: elephantine, phlegmatic, stodgy, clumsy, sluggish) seek desperately to appropriate, in ferocious lech to be metropolitan, the "spirit of Paris" (_American synonyms: silk stockings, "wine," Maxim's, jevousaime, Rat Mort_). Announce they also your "mechanical" pleasures, your weighty light-heartedness, your stolid, stoic essay to take unto yourself, still in tigerish itch to be cosmopolitan, the frou-frouishness of the flirting capital over the frontier. Wise old philosophers! Translating you in terms of your palaces of prostitution, your Palais de Danse, your Admirals-Casinos; translating you in terms of your purposely spurious Victorias, your Riche Cafés, your Fledermauses. As well render the spirit of Vienna in the key of the Kärntnerstrasse at eleven of the Austrian night; as well play the spirit of Paris in the discords of its Montmartre, in the leaden pitch of its Pré Catélan at sunrise. Sing of London from the Astor Club; sing of New York from its Bryant Park at moontide, its Rector's, its ridiculous Café San Souci and its Madam Hunter's. 'Twere the same.

Pleasure in the mass, incidentally, is perforce ever mechanical; a levee at Buckingham Palace, a fête on the velvet terraces sloping into the Newport sea, a Coney Island gangfest, a city's electric den of gilt and tinsel.

But the essence of a city is never here. Berlin, in the wanderlust of its darkened heavens, is not the ample-bosomed, begarneted, crimson-lipped Minna angling in its gaudy dance decoy in the Behrenstrasse; nor the satin-clad, pencilled-eyed Amelie ogling from her "reserved" table in the silly sham called Moulin Rouge; nor yet the more baby-glanced, shirtwaisted Ertrude laughing in the duntoned Café Lang. Berlin is not she who beckons by night in the Friedrich strasse; nor the frowsy she who sings in the _bier-cabarets_ that hover about the Lichtprunksaal. Berlin, under the stars, is the sound of soldiers singing near the arch of the Brandenburger Tor, the peaceful bauer and his frau Hannah and his young daughters Lilla and Mia lodged before their abend bier at a bare table on the darker side of the far Jägerstrasse. Berlin, when skies are navy blue, is Heinrich, gallant rear private of Regiment 31, publicly and with audible ado encircling the waist of his most recent engel on a bench in the Linden promenade—Berlin, in the Inverness of night, is Hulda, little Alsatian rebel—a rebel to France—a rebel to the Vosges and the vineyards—Hulda, the provinces behind her, and in her heart, there to rule forever, the spirit of the capital of Wilhelm der Grösste. For the spirit of Berlin is the laughter of a pretty, clean and healthy girl—not the neurotic simper of a devastated ware of the Madeleine highway, not the raucous giggle of a bark that sails Piccadilly, not the meaningfull and toothy beam of a fair American badger—none of these. It is a laugh that has in it not the motive power of Krug and Company or Ruinart père et fils; it smells not of suspicioned guineas to be enticed; it is not an answer to the baton of necessity. There's heart behind it—and it means only that youth is in the air, that youth and steaming blood and a living life, be the world soever stern on the morrow, are a trinity invincible, unconquerable—that the music is good, the seidel full. Ah, Berlin—ah, Hulda—ah, youth ... ah, youth, what things you see that are not, that never will be, never were; foolish, innocent, splendid youth!

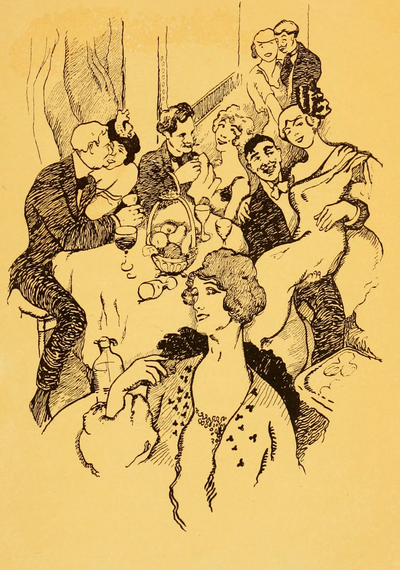

An end to such so tender philosophies, such so blissful ruminations. For even now the kutsche has drawn us up before the door of Herr Kempinski's victual studio, running from the Leipzigerstrasse through to the Krausenstrasse and constituting what is probably the largest stomach Senate and House of Representatives in the seven kingdoms. Here, in the multitudinous säle—the Mosel-saal, the Berliner-saal, the huge Grauer-saal, the Burgen-saal, the Alter-saal, the Erker-saal, the Gelber-saal, the Cadiner-saal, the Eingangs-saal, the Durchgangs-saal, the Brauner-saal and the various other chromatic and geographical saals—one may listen in dyspeptic Anglo-Saxon abashment to such a concerto of down-going suppen and coteletten and gemüse and down-gurgling Laubenheimer and Marcobrunner and Zeltinger and Brauneberger as one may not hear elsewhere in the palatinates. And here, in the preface to the night, one may prehend while again eating (for in Germany, you must know, one's eating is limited in so far as time and occasion are concerned only by the locks of the alimentary canal and the contumacy of the intestines) the grand democracy of this kaiser city. For in this giant eating hall that would hold a round half-dozen New York restaurants and still offer ample elbow room for the dissection of a knuckle and the wielding of a stein, one observes a vast and heterogeneous commingling of the human breed such as may not be observed outside an American charity ball. At one table, a lieutenant of Uhlans with his mädel of the moment, at another a jolly old spitzbub' sending with a loose jest a girl from the chorus of the Theater des Westens into blushes—and being sent himself in return with a looser. At another (one removed from that of a duo of palpable daughters of joy engaged in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter with a colossal roastbif englisch mit Leipziger allerlei) a family man _with_ his family. At still another, another family man with his. At another, the Salome from the Königliches Opernhaus—at another a noted _advokat_—at another, two little girls (they can't he more than sixteen years old) enjoying their meal and their bottle of Rhenish wine undisturbed, unogled, unafraid.

But why need to pursue the catalogue? This, too, is Berlin. Not the Berlin of Herr Adlon's inn, gilded with the leaf of Broadway and the Strand to flabbergast and ensnare the American snooper—not the Berlin of the Bristol, with its imitation cocktails—not the Berlin of the Esplanade, gaudy dump of the Bellevuestrasse, with its sugar tongs, finger bowls and kindred criteria of degeneracy—not this Berlin; but the real Berlin of the German people, warm-hearted, mindful only of its own affairs, all-understanding, all-sympathetic, all-human—its larynx eternally beseeching liquid succour, its stomach eternally demanding chow. And, too—and note this well—not the Berlin of the rouged menu and silk-stockinged kellner, not the trumped-up Berlin of the vaselined vassal, of the bowing oberkellner, not the Berlin of the affected canteloupe ( 3,50 m.) and the affected biscuit tortoni (2,40 m.)—but the Berlin of beinfleisch im kessel mit Meerrettich (90 pf.), the Berlin of kräftbruhe mit nudeln (40 pf.)—the Berlin of Mamsch and Traube.

And now I am again in the streets of the city, rattling with the racing flotilla of things awheel. (Or is the rattle that I hear only the rattle of the "L" trains a block away, and am I really back in New York?) But no; for still I see in the brilliant Berlin moonlight the bronze Quadriga of Victory atop the distant Gate of Brandenburg and still I hear a group of students singing in the Café Mozart, and still—but what is moonlight beside the fairy light in your eyes, fair Hulda? What is song beside the soft melody of your smile? Normandy is in the night air ... "man lacht, man lebt, man liebt und man küsst wo's Küsse giebt" ... and we and all the world are young. Ah, Hulda, mine own, mine all, and who is that pretty girl tripping adown the street, that one there with the corals at her throat and the devil at the curtain of her glance ... and that girl who has just passed, that little minx with eyes like sleeping sapphires and a smile as melodious as mandolins by the summer sea? As melodious as your own, fair Hulda.

* * * * *

The play is over and I have alternated a contemplation of the loves and fears, the tremors and triumphs of some obese stage princess with a lusty entr'-acte excursion into Culmbacher and the cheese sandwich, served, as is the appealing custom, in the theatre promenade. And thus fortified against the night, I pass again into the thoroughfares still a-rattle with the musketry of wheels. I perceive that many amateur American Al-Raschids are abroad in the land, pockets echoing the tintinnabulation of manifold marks and eyes abulge at the prospect of midnight diableries. See that fellow yonder! At home, probably a family man, a wearer of mesh underwear, an assiduous devourer of the wisdom of George Harvey, a patron of the dramas of Charles Rann Kennedy, a spanker of children, an entertainer at his board of the visiting clergyman, a pantophagous subscriber, a silk hat wearer—in brief, a leading citizen. See him oleaginate his grin at the sight of a passing painted paver. (To his mind, probably a barmaid out for an innocent lark.) See him make for the Palais de Danse where (so he has read in the Saturday Evening Post) one may purchase the Berliner spirit at so much per pound. We track him, and presently we behold him seated at a table in this splendiferous hall of Terpsichore and Thaïs "opening wine" and purchasing blumen for a battle-scarred veteran who is telling him confidentially that she just got in that afternoon from her poor home in a little Bavarian village and that she feels so alone in this big, great city, with its lures and temptations, its snares and its pitfalls. Soon the bubbles of the grape are percolating through his arteries and soon the "Grosse Rosinen" waltzes have mellowed his conscience and soon....

* * *

"Berlin spirit, huh!" he is telling his wife a month later—"Berlin spirit? All artificial. Just to make money out of the visitors. And very sordid!"

* * *

At the Moulin Rouge and at the Admirals-Casino, at the Alhambra and the Tabarin, at the Amor-säle and the Rosen-säle, we track down others such, "seeing the night life of Berlin." We see them, too, champagne before them, coquetting with Fräulein Ilona, who numbers Militär-Regiment 42 as her gentleman friend, and with innocent-looking little Hedwig, who in her day has tramped the streets of Brussels and Paris, of London and Vienna; we see them intriguing elaborately with these sisters of sorrow, who, intriguing in turn against the night's wage, assist the skirmish on with incendiary quip and tender touch of foot and similar cantharides of financial amour. And we track them later to such institutions as the Fledermaus—"der grosse luxuriöse, vornehmstes vergnügungsplatz, paradiesgarten, grösste sehenswürdigkeit Berlins" (in the advertisements)—as the Victoria and the Café Riche, the Westminster and the Café Opéra and—

* * *

"Berlin spirit, huh!" they are telling their wives a month later—"Berlin spirit? All artificial. Just to make money out of the visitors. And very sordid!"

* * *

Ah, Cairo dreaming in the Nile's moon-haze—are you to be judged thus by the narrow street that snakes into the dark of Bulak? And Budapest by the Danube—are you to be judged by the wreckage of the Stefansplatz that has drifted on your shores? And you, Vienna, and you, Paris— are you, too, to be measured thus, as measured you are, by the crimson light of your half-worlds that for some obscures your stars?

The Berlin of the Palais de Danse is the Paris of L'Abbaye; the Berlin of the Fledermaus is the New York of Jack's.

But the Berlin that I know and love is not this Berlin, the Berlin of Americans, not the spangled Berlin, the hollow-laughing Berlin, the Berlin decked with rhinestones, set alight with prismatic electroliers and offered up as mistress to foreign gold. When the River Spree is amethystine under springtime skies and the city's lights are yellow in the linden trees, I like best the Berlin that sips its beer in the peace of the little by-streets, the Berlin that laughs in the Tiergarten near the Lake of the Goldfish and on the Isle of Louisa, where watch throughout eternity the graven images of Friedrich Wilhelm the Third and of Wilhelm the First in the years of his boyhood. I like best the Berlin that sings with the students in the undiscovered, untainted wein and bier stuben of the thitherward thoroughfares, the Berlin that dances in the Joachimstrasse, where the mädels, each to herself a Cecilie, shirtwaisted, poor, happy, kick up their German heels, drink up their German beer, assault the Schweizerkäse and bring back memories of that paradise of all paradises—the Englischer Garten of Munich the Incomparable, the Divine.

In such phases of this kaiser city, one is removed from the so-called Tingel-Tangel, or variétés and cabarets, where the visiting narrverein is regaled with such integral and valid elements of Berlin "night life" as "der cake walk," "der can-can" and "die matschiche—getanzt von original importierten Mexikanerinnen." So, too, is one removed from the garish demi-women of the so-called "Quartier Latin" near the Oranienburger Tor and from the spurious deviltries of the Rothenburger Krug and the Staffelstein, with their "property" students, cheeks scarred with red ink, singing "Heidelberg" (from "The Prince of Pilsen") for the edification and impression of foreign visitors, and fiercely and frequently challenging other prop. students to immediate duel. The girls, alas, in these places are not unlovely. Well do I remember the dainty Elsa of the Hopfenblüthe, she of face kissed by the Prussian dawn, and employed at sixteen marks the week to wink dramatically at the old roués and give the resort "an air." Well does memory repeat to me the loveliness of delicate little Anna, she with hair like the waving golden grass in the fields that skirt the roadways from Targon to Villandraut, and paid so much the month to laugh uproariously every time the hands of the clock point the quarter-hour. And Rika and Dessa and Julia and Paulina—all sweet of look, all professional actresses; Bernhardts of Fun (inc.), Duses of Pleasure (ltd.). Not the girls in whose hearts Berlin is beating, not the girls in whose élan Berlin lives and laughs. Leave behind all places such as these, seeker after the soul of Berlin. Leave behind the Tingel-Tangel with its uniformed bouncer at the gate, with its threadbare piano, with its "na kleener Dicker" smirked by soiled decolletés, its doleful near-naughty ditties—"Ich lass mich nicht verführen, dazu bin ich zu schlau, ich kenne die Manieren der Männer ganz genau"—"I won't be led astray, I am too slick for that, I know the ways of mankind, I've got them all down pat." Leave behind the Berlin of the Al-Raschids and keep to the Berlin of the Germans.

Just as the worst of Paris came from America, so has the worst of Berlin come from America by way of Paris. The maquereau spirit of Montmartre, with its dollar lust and its poisoned blood, has not yet the throat of this German night city full in its fists; but the fists are tightening slowly—and the voice behind them speaks not French, but the jargon of Broadway. And yet, when finally the fingers work closer, closer still, around that throat, when finally the death gurgle of spontaneous pleasure and of clean, honest, fearless night skies comes—and yet, when this happens, Berlin will still rise from the dunghill. I must believe it. For they—we—may kill the laughter of Berlin's streets—as we have killed it in Paris—but we can never kill the heart, the spirit and the living, quivering corpuscles of German blood. The French may drink stronger stuffs, eat richer foods and love oftener than the Germans, and may be better fighters—but they cannot laugh, they cannot sing as the Germans laugh and sing. And Berlin is the new Germany, the Germany of to-day and to-morrow ... the Germany whose laughter will grow louder as the decades pass and whose song will echo clearer from the distant hills. While Paris (to go to Conrad)—is not Paris and her land already at Bankok, and far, far beyond? Her children spent before their day, listening to the too-soon lecture of Time? And all hopelessly nodding at him: "the man of finance, the man of accounts, the man of law, we all nodded at him over the polished table that like a still sheet of brown water reflected our faces, lined, wrinkled; our faces marked by toil, by deceptions, by success, by love; our weary eyes looking still, looking always, looking anxiously for something out of life, that while it is expected is already gone—has passed unseen, in a sigh, in a flash—together with the youth, with the strength, with the romance of illusions...."

But again a truce to philosophisings. It grows late apace. (Ah, Hulda, how like opals in the lyric April rain are your eyes in this first faint purple-pink of the tremulous dawn.... Were I a Heine!) In my far-away America, Hulda, in far-away New York, it is now onto midnight. I see Broadway, strumpet of the highways, sweltering collarless under the loud electricity of Times Square. I see a fetid blonde, dangling a patent leather handbag, hurrying to an assignation in Forty-fifth Street. I see two actors, pointing their boasts with yellow bamboo canes. A chop suey restaurant flashes its sign. And I can hear the racking ragtime out of Shanley's. A big sightseeing bus is howling the fictitious lure of the Bowery, Chinatown and the Ghetto to gaping groups from the hinterlands. A streetwalker. Another. Another. In the subway entrance across the street, a blind man is selling papers. A "dip" calls a friendly "Hello, Dan" to the policeman in front of the drugstore and works his steps over the car tracks toward the drunk teetering against the window of the Jew's clothing store. The air is dust-filled. An intermittent baking gust from the river sends a cast-aside Journal fluttering aloft. A dirt-encrusted bum begs the price of a coffee. Another streetwalker, appearing from the backwaters of Seventh Avenue, grins in the drugstore's green light....

But to your eyes, Hulda, must be given no such picture. Yet such is the New York I come from; such the New York, stunning by day in its New World strength and splendour, loathsome by night in its hot, illumined bawdry. Ah, city by the Hudson, forgetting Riverside Drive twinkling amid the long tiara of trees, forgetting the still of the lake and cool of the boulders that plead in Central Park, forgetting the superb majesty of Cathedral Heights and the mighty peace of the byways—forgetting these all for a Broadway!

But the symphony of the Berlin dawn is ours now, fräulein, and have done with intrusive memories, corroding reflections. What are my people doing in Berlin at this hour? What are these prowling Al-Raschids about? Do they know the sorcery of the virgin morning light of Berlin as it falls upon the Siegesallee and gives life again to the marble heroes of Germany? Have they ever stood with such as you, fräulein, in the coral-tipped hours of the dawning day before the image of Friedrich der Grosse in that wonderful lane and felt, through this dead, cold thing, the thrill of an empire's glory? Do they know the witchery of the withering Berlin night as it plays out its wild fantasia in the leaves of the Linden trees? Have they ever been with such as you, fräulein, at the base of the Pillar of Triumph in Königsplatz or sat with such as you, fräulein, near the Grotto Lake in the Tiergarten, or stood with such as you, fräulein, on one of the bridges arching the Spree in the first trembling innuendo of morning?

Where are these, my people?

You will find them seeking the romance of Berlin's greying night amid the Turkish cigarette smoke and stale wine smells of the half-breed cabarets marshalled along the Jägerstrasse, the Behrenstrasse and their tributaries. You will find them up a flight of stairs in one of the all-night Linden cafés, throwing celluloid balls at the weary, patient, left-over women. You will find them sitting in the balcony of the Pavilion Mascotte, blowing up toy balloons and hurling small cones of coloured paper down at the benign harlotry. You will see them, hatless, shooting up the Friedrichstrasse in an open taxicab, singing "Give My Regards to Broadway" in all the prime ecstasy of a beer souse. You will find them in the rancid Tingel-Tangel, blaspheming the kellner because they can't get a highball. You will find them in the Nollendorfplatz gaping at the fairies. You will see them, green-skinned in the tyrannic light of early morning, battering at the iron grating of their hotel for the porter to open up and let them in.

For them, are no souvenirs of happy evening hours that sing always in the heart of a Berlin they can never know. For them, shall be no memory of that vast and insuperable gemütlichkeit, that superb and pacific democracy, that dwells and shall dwell forever by night in the spirit of the German people. They will never know the Berlin that lifts its seidel to the setting sun, the Berlin that greets the moonrise, the Berlin that meets the dawn. The Berlin that they know is a Berlin of French champagnes, Italian confetti, Spanish dancers, English-trained waiters, Austrian courtesans and American hilarities. They interpret a city by its leading all-night restaurant; a nation by the demi-mondaine who happens to be nearest their table. For them, there is no—

But hark, what is that?

What is that strange sound that comes to me?

* * *

"Extra! Evening Telegram, extra! All 'bout the Giants win double-header!"

* * *

A newsboy in neuralgic yowl, bawling in the street below.

Alas, it is true: after all, I am really back again in New York. My rooms are littered with battered bags and down-at-the-heel walking sticks and still-damp steamer rugs, lying where they dropped from the hands of maudlin bellboys. My trunks are creaking their way down the hall, urged on by a perspiring, muttering porter. The windows, still locked and gone blue-grey with the August heat, rattle to the echo of the rankling "L" trains. The last crack of a triphammer, peckering at a giant pile of iron down the block, dies out on the dead air. A taxicab, rrrrr-ing in the street below, grunts its horn. Another "L" train and the panes rattle again. A momentary quiet ... and from somewhere in a nearby street I hear again the grind-organ.

It is playing "Alexander's Ragtime Band."