MUNICH

MUNICH

MUNICH

LET the most important facts come first. The best beer in Munich is Spatenbräu; the best place to get it is at the Hoftheatre Café in the Residenzstrasse; the best time to drink it is after 10 p. m., and the best of all girls to serve it is Fräulein Sophie, that tall and resilient creature, with her appetizing smile, her distinguished bearing and her superbly manicured hands.

I have, in my time, sat under many and many superior kellnerinen, some as regal as grand duchesses, some as demure as shoplifters, some as graceful as prime ballerini, but none reaching so high a general level of merit, none so thoroughly satisfying to eye and soul as Fräulein Sophie. She is a lady, every inch of her, a lady presenting to all gentlemanly clients the ideal blend of cordiality and dignity, and she serves the best beer in Christendom. Take away that beer, and it is possible, of course, that Sophie would lose some minute granule or globule of her charm; but take away Sophie and I fear the beer would lose even more.

In fact, I know it, for I have drunk that same beer in the Spatenbräukeller in the Bayerstrasse, at all hours of the day and night, and always the ultimate thrill was missing. Good beer, to be sure, and a hundred times better than the common brews, even in Munich, but not perfect beer, not beer de luxe, not super-beer. It is the human equation that counts, in the bierhalle as on the battlefield. One resents, somehow a kellnerin with the figure of a taxicab, no matter how good her intentions and fluent her technique, just as one resents a trained nurse with a double chin or a glass eye. When a personal office that a man might perform, or even an intelligent machine, is put into the hands of a woman, it is put there simply and solely because the woman can bring charm to it and irradiate it with romance. If, now, she fails to do so—if she brings, not charm, not beauty, not romance, but the gross curves of an aurochs and a voice of brass—if she offers bulk when the heart cries for grace and adenoids when the order is for music, then the whole thing becomes a hissing and a mocking, and a grey fog is on the world.

But to get back to the Hoftheatre Café. It stands, as I have said, in the Residenzstrasse, where that narrow street bulges out into the Max-Joseph-platz, and facing it, as its name suggests, is the Hoftheatre, the most solemn-looking playhouse in Europe, but the scene of appalling tone debaucheries within. The supreme idea at the Hoftheatre is to get the curtain down at ten o'clock. If the bill happens to be a short one, say "Hänsel and Gretel" or "Elektra," the three thumps of the starting mallet may not come until eight o'clock or even 8:30, but if it is a long one, say "Parsifal" or "Les Huguenots," a beginning is made far back in the afternoon. Always the end arrives at ten, with perhaps a moment or two leeway in one direction or the other. And two minutes afterward, without further ceremony or delay, the truly epicurean auditor has his feet under the mahogany at the Hoftheatre Café across the platz, with a seidel of that incomparable brew tilted elegantly toward his face and his glad eyes smiling at Fräulein Sophie through the glass bottom.

How many women could stand that test? How many could bear the ribald distortions of that lens-like seidel bottom and yet keep their charm? How many thus caricatured and vivisected, could command this free reading notice from a casual American, dictating against time and space to a red-haired stenographer, three thousand and five hundred miles away? And yet Sophie does it, and not only Sophie, but also Frida, Elsa, Lili, Kunigunde, Märtchen, Thérèse and Lottchen, her confrères and aides, and even little Rosa, who is half Bavarian and half Japanese, and one of the prettiest girls in Munich, in or out of uniform. It is a pleasure to say a kind word for little Rosa, with her coal black hair and her slanting eyes, for she is too fragile a fräulein to be toting around those gigantic German schnitzels and bifsteks, those mighty double portions of sauerbraten and rostbif, those staggering drinking urns, overballasted and awash.

Let us not, however, be unjust to the estimable Herr Wirt of the Hoftheatre Café, with his pneumatic tread, his chaste side whiskers and his long-tailed coat, for his drinking urns, when all is said and done, are quite the smallest in Munich. And not only the smallest, but also the shapeliest. In the Hofbräuhaus and in the open air _bierkneipen_ (for instance, the Mathäser joint, of which more anon) one drinks out of earthen cylinders which resemble nothing so much as the gaunt towers of Munich cathedral; and elsewhere the orthodox goblet is a glass edifice following the lines of an old-fashioned silver water pitcher—you know the sort the innocently criminal used to give as wedding presents!—but at the Hoftheatre there is a vessel of special design, hexagonal in cross section and unusually graceful in general aspect. On top, a pewter lid, ground to an optical fit and highly polished—by Sophie, Rosa et al., poor girls! To starboard, a stout handle, apparently of reinforced onyx. Above the handle, and attached to the lid, a metal flange or thumbpiece. Grasp the handle, press your thumb on the thumbpiece—and presto, the lid heaves up. And then, to the tune of a Strauss waltz, played passionately by tone artists in oleaginous dress suits, down goes the Spatenbräu—gurgle, gurgle—burble, burble—down goes the Spatenbräu—exquisite, ineffable!—to drench the heart in its nut brown flood and fill the arteries with its benign alkaloids and antitoxins.

Well, well, maybe I grow too eloquent! Such memories loose and craze the tongue. A man pulls himself up suddenly, to find that he has been vulgar. If so here, so be it! I refuse to plead to the indictment; sentence me and be hanged to you! I am by nature a vulgar fellow. I prefer "Tom Jones" to "The Rosary," Rabelais to the Elsie books, the Old Testament to the New, the expurgated parts of "Gulliver's Travels" to those that are left. I delight in beef stews, limericks, burlesque shows, New York City and the music of Haydn, that beery and delightful old rascal! I swear in the presence of ladies and archdeacons. When the mercury is above ninety-five I dine in my shirt sleeves and write poetry naked. I associate habitually with dramatists, bartenders, medical men and musicians. I once, in early youth, kissed a waitress at Dennett's. So don't accuse me of vulgarity; I admit it and flout you. Not, of course, that I have no pruderies, no fastidious metes and bounds. Far from it. Babies, for example, are too vulgar for me; I cannot bring myself to touch them. And actors. And evangelists. And the obstetrical anecdotes of ancient dames. But in general, as I have said, I joy in vulgarity, whether it take the form of divorce proceedings or of "Tristan und Isolde," of an Odd Fellows' funeral or of Munich beer.

But here, perhaps, I go too far again. That is to say, I have no right to admit that Munich beer is vulgar. On the contrary, it is my obvious duty to deny it, and not only to deny it but also to support my denial with an overwhelming mass of evidence and a shrill cadenza of casuistry. But the time and the place, unluckily enough, are not quite fit for the dialectic, and so I content myself with a few pertinent observations. Imprimis, a thing that is unique, incomparable, sui generis, cannot be vulgar. Munich beer is unique, incomparable, sui generis. More, it is consummate, transcendental, übernatürlich. Therefore it cannot be vulgar. Secondly, the folk who drink it day after day do not die of vulgar diseases. Turn to the subhead Todesursachen in the instructive Statistischer Monatsbericht der Stadt München, and you will find records of few if any deaths from delirium tremens, boils, hookworm, smallpox, distemper, measles or what the Monatsbericht calls "liver sickness." The Müncheners perish more elegantly, more charmingly than that. When their time comes it is gout that fetches them, or appendicitis, or neurasthenia, or angina pectoris; or perchance they cut their throats.

Thirdly, and to make it short, lastly, the late Henrik Ibsen, nourished upon Munich beer, wrote "Hedda Gabler," not to mention "Rosmersholm" and "The Lady from the Sea"—wrote them in his flat in the Maximilianstrasse overlooking the palace and the afternoon promenaders, in the late eighties of the present, or Christian era—wrote them there and then took them to the Café Luitpold, in the Briennerstrasse, to ponder them, polish them and make them perfect. I myself have sat in old Henrik's chair and victualed from the table. It is far back in the main hall of the café, to the right as you come in, and hidden from the incomer by the glass vestibule which guards the pantry. Ibsen used to appear every afternoon at three o'clock, to drink his vahze of Löwenbräu and read the papers. The latter done, he would sit in silence, thinking, thinking, planning, planning. Not often did he say a word, even to Fräulein Mizzi, his favourite kellnerin. So taciturn was he, in truth, that his rare utterances were carefully entered in the archives of the café and are now preserved there. By the courtesy of Dr. Adolph Himmelheber, the present curator, I am permitted to transcribe a few, the imperfect German of the poet being preserved:

November 18, 1889, 4:15 P.M.—Giebt es kein Feuer in diese verfluchte Bierstube? Meine Füsse sind so kalt wie Eiszapfen!

April 12, 1890, 5:20 P.M.—Der Kerl is verrückt! (Said of an American who entered with the stars and stripes flying from his hat.)

May 22, 1890, 4:40 P.M.—Sie sind so eselhaft wie ein Schauspieler! (To an assistant Herr Wirt who brought him a Socialist paper in mistake for the London Times.)

Now and then the great man would condescend to play a game of billiards in the hall to the rear, usually with some total stranger. He would point out the stranger to Fräulein Mizzi and she would carry his card. The game would proceed, as a rule, in utter silence. But it was for the Löwenbräu and not for the billiards that Ibsen came to the Luitpold, for the Löwenbräu and the high flights of soul that it engendered. He had no great liking for Munich as a city; his prime favourite was always Vienna, with Rome second. But he knew that the incomparable malt liquor of Munich was full of the inspiration that he needed, and so he kept near it, not to bathe in it, not to frivol with it, but to take it discreetly and prophylactically, and as the exigencies of his art demanded.

Ibsen's inherent fastidiousness, a quality which urged him to spend hours shining his shoes, was revealed by his choice of the Café Luitpold, for of all the cafés in Munich the Luitpold is undoubtedly the most elegant. Its walls are adorned with frescoes by Albrecht Hildebrandt. The ceiling of the main hall is supported by columns of coloured marble. The tables are of carved mahogany. The forks and spoons, before Americans began to steal them, were of real silver. The chocolate with whipped cream, served late in the afternoon, is famous throughout Europe. The Herr Wirt has the suave sneak of John Drew and is a privy councillor to the King of Bavaria. All the tables along the east wall, which is one vast mirror, are reserved from 8 P.M. to 2 A.M. nightly by the faculty of the University of Munich, which there entertains the eminent scientists who constantly visit the city. No orchestra arouses the baser passions with "Wiener Blut." The place has calm, aloofness, intellectuality, aristocracy, distinction. It was the scene foreordained for the hatching of "Hedda Gabler."

But don't imagine that Munich, when it comes to elegance, must stand or fall with the Luitpold. Far from it, indeed. There are other cafés of noble and elevating quality in that delectable town—plenty of them, you may be sure. For example, the Odéon, across the street from the Luitpold, a place lavish and luxurious, but with a certain touch of dogginess, a taste of salt. The piccolo who lights your cigar and accepts your five pfennigs at the Odéon is an Ethiopian dwarf. Do you sense the romance, the exotic diablerie, the suggestion of Levantine mystery? And somewhat Levantine, too, are the ladies who sit upon the plush benches along the wall and take Russian cigarettes with their kirschenwasser. Not that the atmosphere is frankly one of Sin. No! No! The Odéon is no cabaret. A leg flung in the air would bring the Herr Wirt at a gallop, you may be sure—or, at any rate, his apoplectic corpse. In all New York, I dare say, there is no public eating house so near to the far-flung outposts, the Galapagos Islands of virtue. But one somehow feels that for Munich, at least, the Odéon is just a bit tolerant, just a bit philosophical, just a bit Bohemian. One even imagines taking an American show girl there without being warned (by a curt note in one's serviette) that the head waiter's family lives in the house.

Again, pursuing these haunts of the baroque and arabesque, there is the restaurant of the Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten, a masterpiece of the Munich glass cutters and upholsterers. It is in the very heart of things, with the royal riding school directly opposite, the palace a block away and the green of the Englischer Garten glimmering down the street. Here, of a fine afternoon, the society is the best between Vienna and Paris. One may share the vinegar cruet with a countess, and see a general of cavalry eat peas with a knife (hollow ground, like a razor; a Bavarian trick!) and stand aghast while a great tone artist dusts his shoes with a napkin, and observe a Russian grand duke at the herculean labour of drinking himself to death.

The Vier Jahreszeiten is no place for the common people; such trade is not encouraged. The dominant note of the establishment is that of proud retirement, of elegant sanctuary. One enters, not from the garish Maximilianstrasse, with its motor cars and its sinners, but from the Marstallstrasse, a sedate and aristocratic side street. The Vier Jahreszeiten, in its time, has given food, alcohol and lodgings for the night to twenty crowned heads and a whole shipload of lesser magnificoes, and despite the rise of other hotels it retains its ancient supremacy. It is the peer of Shepheard's at Cairo, of the Cecil in London, of the old Inglaterra at Havana, of the St. Charles at New Orleans. It is one of the distinguished hotels of the world.

I could give you a long list of other Munich restaurants of a kingly order—the great breakfast room of the Bayrischer Hof, with its polyglot waiters and its amazing repertoire of English jams; the tea and liquor atelier of the same hostelry, with its high dome and its sheltering palms; the pretty little open air restaurant of the Künstlerhaus in the Lenbachplatz; the huge catacomb of the Rathaus, with its mediæval arches and its vintage wines; the lovely al fresco café on Isar Island, with the green cascades of the Isar winging on lazy afternoons; the café in the Hofgarten, gay with birds and lovers; that in the Tiergarten, from the terrace of which one watches lions and tigers gamboling in the woods; and so on, and so on. There is even, I hear, a temperance restaurant in Munich, the Jungbrunnen in the Arcostrasse, where water is served with meals, but that is only rumour. I myself have never visited it, nor do I know any one who has.

All this, however, is far from the point. I am here hired to discourse of Munich beer, and not of vintage wines, bogus cocktails, afternoon chocolate and well water. We are on a beeriad. Avaunt, ye grapes, ye maraschino cherries, ye puerile H_{2}O!

And so, resuming that beeriad, it appears that we are once again in the Hoftheatre Café in the Residenzstrasse, and that Fräulein Sophie, that pleasing creature, has just arrived with two ewers of Spatenbräu— two ewers fresh from the wood—woody, nutty, incomparable! Ah, those elegantly manicured hands! Ah, that Mona Lisa smile! Ah, that so graceful waist! Ah, malt! Ah, hops! Ach, München, wie bist du so schön!

But even Paradise has its nuisances, its scandals, its lacks. The Hoftheatre Café, alas, is not the place to eat sauerkraut—not the place, at any rate, to eat sauerkraut de luxe, the supreme and singular masterpiece of the Bavarian uplands, the perfect grass embalmed to perfection. The place for that is the Pschorrbräu in the Neuhauserstrasse, a devious and confusing journey, down past the Pompeian post office, into the narrow Schrammerstrasse, around the old cathedral, and then due south to the Neuhauserstrasse. Sapperment! The Neuhauserstrasse is here called the Kaufingerstrasse! Well, well, don't let it fool you. A bit further to the east it is called the Marienplatz, and further still the Thal, and then the Isarthorplatz, and then the Zweibrückenstrasse, and then the Isarbrücke, and then the Ludwigbrücke, and finally, beyond the river, the Gasteig or the Rosenheimerstrasse, according as one takes its left branch or its right.

But don't be dismayed by all that versatility. Munich streets, like London streets, change their names every two or three blocks. Once you arrive between the two mediæval arches of the Karlsthor and the Sparkasse, you are in the Neuhauserstrasse, whatever the name on the street sign, and if you move westward toward the Karlsthor you will come inevitably to the Pschorrbräu, and within you will find Fräulein Tilde (to whom my regards), who will laugh at your German with a fine show of pearly teeth and the extreme vibration of her 195 pounds. Tilde, in these godless states, would be called fat. But observe her in the Pschorrbräu, mellowed by that superb malt, glorified by that consummate kraut, and you will blush to think her more than plump.

I give you the Pschorrbräu as the one best eating bet in Munich—and not forgetting, by any means, the Luitpold, the Rathaus, the Odéon and all the other gilded hells of victualry to northward. Imagine it: every skein of sauerkraut is cooked three times before it reaches your plate! Once in plain water, once in Rhine wine and once in melted snow! A dish, in this benighted republic, for stevedores and yodlers, a coarse fee for violoncellists, barbers and reporters for the Staats-Zeitung—but the delight, at the Pschorrbräu, of diplomats, the literati and doctors of philosophy. I myself, eating it three times a day, to the accompaniment of schweinersrippen and bonensalat, have composed triolets in the Norwegian language, a feat not matched by Björnstjerne Björnson himself. And I once met an American medical man, in Munich to sit under the learned Prof. Dr. Müller, who ate no less than five portions of it nightly, after his twelve long hours of clinical prodding and hacking. He found it more nourishing, he told me, than pure albumen, and more stimulating to the jaded nerves than laparotomy.

But to many Americans, of course, sauerkraut does not appeal. Prejudiced against the dish by ridicule and innuendo, they are unable to differentiate between good and bad, and so it's useless to send them to this or that ausschank. Well, let them then go to the Pschorrbräu and order bifstek from the grill, at M. 1.20 the ration. There may be tenderer and more savoury bifsteks in the world, bifsteks which sizzle more seductively upon red hot plates, bifsteks with more proteids and manganese in them, bifsteks more humane to ancient and hyperesthetic teeth, bifsteks from nobler cattle, more deftly cut, more passionately grilled, more romantically served—but not, believe me, for M. 1.20! Think of it: a cut of tenderloin for M. 1.20—say, 28.85364273x cents! For a side order of sauerkraut, forty pfennigs extra. For potatoes, twenty-five pfennigs. For a mass of dunkle, thirty-two pfennigs. In all, M. 2.17—an odd mill or so more or less than fifty-two cents. A square meal, perfectly cooked, washed down with perfect beer and served perfectly by Fräulein Tilde—and all for the price of a shampoo!

From the Pschorrbräu, if the winds be fair, the beeriad takes us westward along the Neuhauserstrasse a distance of eighty feet and six inches, and behold, we are at the Augustinerbräu. Good beer—a trifle pale, perhaps, and without much grip to it, but still good beer. After all, however, there is something lacking here. Or, to be more accurate, something jars. The orchestra plays Grieg and Moszkowski; a smell of chocolate is in the air; that tall, pink lieutenant over there, with his cropped head and his outstanding ears, his backfisch waist and his mudscow feet—that military gargoyle, half lout and half fop, offends the roving eye. No doubt a handsome man, by German standards—even, perhaps a celebrated seducer, a soldier with a future—but the mere sight of him suffices to paralyse an American esophagus. Besides, there is the smell of chocolate, sweet, sickly, effeminate, and at two in the afternoon! Again, there is the music of Grieg, clammy, clinging, creepy. Away to the Mathäserbräu, two long blocks by taxi! From the Munich of Berlinish decadence and Prussian epaulettes to the Munich of honest Bavarians! From chocolate and macaroons to pretzels and white radishes! From Grieg to "Lachende Liebe!" From a boudoir to an inn yard! From pale beer in fragile glasses to red beer in earthen pots!

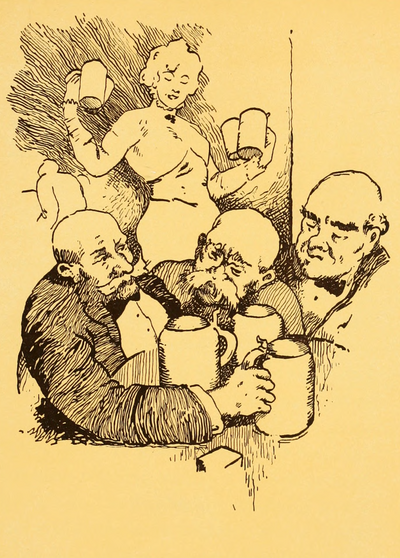

The Mathäserbräu is up a narrow alley, and that alley is always full of Müncheners going in. Follow the crowd, and one comes presently to a row of booths set up by radish sellers—ancient dames of incredible diameter, gnarled old peasants in tapestry waistcoats and country boots; veterans, one half ventures, of the Napoleonic wars, even of the wars of Frederick the Great. A ten-pfennig piece buys a noble white radish, and the seller slices it free of charge, slices it with a silver revolving blade into two score thin schnitzels, and puts salt between each adjacent pair. A radish so sliced and salted is the perfect complement of this dark Mathäser beer. One nibbles and drinks, drinks and nibbles, and so slides the lazy afternoon. The scene is an incredible, playhouse courtyard, with shrubs in tubs and tables painted scarlet; a fit setting for the first act of "Manon." But instead of choristers in short skirts, tripping, the whoop-la and boosting the landlord's wine, one feasts the eye upon Münchenese of a rhinocerous fatness, dropsical and gargantuan creatures, bisons in skirts, who pass laboriously among the bibuli, offering bunches of little pretzels strung upon red strings. Six pretzels for ten pfennigs. A five-pfennig tip for Frau Dickleibig, and she brings you the Fliegende Blätter, Le Rire, the Munich or Berlin papers, whatever you want. A drowsy, hedonistic, easy-going place. Not much talk, not much rattling of crockery, not much card playing. The mountain, one guesses, of Munich meditation. The incubator of Munich gemütlichkeit.

Upstairs there is the big Mathäser hall, with room for three thousand visitors of an evening, a great resort for Bavarian high privates and their best girls, the scene of honest and public courting. Between the Bavarian high private and the Bavarian lieutenant all the differences are in favour of the former. He wears no corsets, he is innocent of the monocle, he sticks to native beer. A man of amour like his officer, he disdains the elaborate winks, the complex diableries of that superior being, and confines himself to open hugging. One sees him, in these great beer halls, with his arm around his Lizzie. Anon he arouses himself from his coma of love to offer her a sip from his _mass_ or to whisper some bovine nothing into her ear. Before they depart for the evening he escorts her to the huge sign, "Für Damen," and waits patiently while she goes in and fixes her mussed hair.

The Bavarians have no false pruderies, no nasty little nicenesses. There is, indeed, no race in Europe more innocent, more frank, more clean-minded. Postcards of a homely and harmless vulgarity are for sale in every Munich stationer's shop, but the connoisseur looks in vain for the studied indecencies of Paris, the appalling obscenities of the Swiss towns. Munich has little to show the American Sunday school superintendent on the loose. The ideal there is not a sharp and stinging deviltry, a swift massacre of all the commandments, but a liquid and tolerant geniality, a great forgiveness. Beer does not refine, perhaps, but at any rate it mellows. No Münchener ever threw a stone.

And so, passing swiftly over the Burgerbräu in the Kaufingerstrasse, the Hackerbräu, the Kreuzbräu, and the Kochelbräu, all hospitable lokale, selling pure beer in honest measures; and over the various Pilsener fountains and the agency for Vienna beer—dish-watery stuff!—in the Maximilianstrasse; and over the various summer keller on the heights of Au and Haidhausen across the river, with their spacious terraces and their ancient traditions—passing over all these tempting sanctuaries of mass and kellnerin, we arrive finally at the Löwenbräukeller and the Hofbräuhaus, which is quite a feat of arriving, it must be granted, for the one is in the Nymphenburgerstrasse, in Northwest Munich, and the other is in the Platzl, not two blocks from the royal palace, and the distance from the one to the other is a good mile and a half.

The Löwenbräu first—a rococo castle sprawling over a whole city block, and with accommodations in its "halls, galleries, loges, verandas, terraces, outlying garden promenades and beer rooms" (I quote the official guide) for eight thousand drinkers. A lordly and impressive establishment is this Löwenbräu, an edifice of countless towers, buttresses, minarets and dungeons. It was designed by the learned Prof. Albert Schmidt, one of the creators of modern Munich, and when it was opened, on June 14, 1883, all the military bands in Munich played at once in the great hall, and the royal family of Bavaria turned out in state coaches, and 100,000 eager Müncheners tried to fight their way in.

How large that great hall may be I don't know, but I venture to guess that it seats four thousand people—not huddled together, as a theatre seats them, but comfortably, loosely, spaciously, with plenty of room between the tables for the 250 kellnerinen to navigate safely with their cargoes of Löwenbräu. Four nights a week a military band plays in this hall or a männerchor rowels the air with song, and there is an admission fee of thirty pfennigs (7-1/5 cents). One night I heard the band of the second Bavarian (Crown Prince's) Regiment, playing as an orchestra, go through a programme that would have done credit to the New York philharmonic. A young violinist in corporal's stripes lifted the crowd to its feet with the slow movement of the Tschaikowsky concerto; the band itself began with Wagner's "Siegfried Idyl" and ended with Strauss's "Rosen aus dem Süden," a superb waltz, magnificently performed. Three hours of first-rate music for 7-1/5 cents! And a mass of Löwenbräu, twice the size of the seidel sold in this country at twenty cents, for forty pfennigs (9-1/2 cents)! An inviting and appetizing spot, believe me. A place to stretch your legs. A temple of Lethe. There, when my days of moneylust are over, I go to chew my memories and dream my dreams and listen to my arteries hardening.

By taxicab down the wide Briennerstrasse, past the Luitpold and the Odéon, to the Ludwigstrasse, gay with its after-the-opera crowds, and then to the left into the Residenzstrasse, past the Hoftheatre and its café (ah, Sophie, thou angel!), and so to the Maximilianstrasse, to the Neuthurmstrasse, and at last, with a sharp turn, into the Platzl.

The Hofbräuhaus! One hears it from afar; a loud buzzing, the rattle of mass lids, the sputter of the released dunkle, the sharp cries of pretzel and radish sellers, the scratching of matches, the shuffling of feet, the eternal gurgling of the plain people. No palace this, for all its towering battlements and the frescos by Ferdinand Wagner in the great hall upstairs, but drinking butts for them that labour and are heavy laden: station porter, teamsters, servant girls, soldiers, bricklayers, blacksmiths, tinners, sweeps.

There sits the fair lady who gathers cigar stumps from the platz in front of the Bayerischer Hof, still in her green hat of labour, but now with an earthen cylinder of Hofbräu in her hands. The gentleman beside her, obviously wooing her, is third fireman at the same hotel. At the next table, a squad of yokels just in from the oberland, in their short jackets and their hobnailed boots. Beyond, a noisy meeting of Socialists, a rehearsal of some liedertafel, a family reunion of four generations, a beer party of gay young bloods from the gas works, a conference of the executive committee of the horse butchers' union. Every second drinker has brought his lunch wrapped in newspaper; half a blutwurst, two radishes, an onion, a heel of rye bread. The débris of such lunches covers the floor. One wades through escaped beer, among floating islands of radish top and newspaper. Children go overboard and are succoured with shouts. Leviathans of this underground lake, Lusitanias of beer, Pantagruels of the Hofbräuhaus, collide, draw off, collide again and are wrecked in the narrow channels.... A great puffing and blowing. Stranded craft on every bench.... Noses like cigar bands.

No waitresses here. Each drinker for himself! You go to the long shelf, select your mass, wash it at the spouting faucet and fall into line. Behind the rail the zahlmeister takes your twenty-eight pfennigs and pushes your mass along the counter. Then the perspiring bierbischof fills it from the naked keg, and you carry it to the table of your choice, or drink it standing up and at one suffocating gulp, or take it out into the yard, to wrestle with it beneath the open sky. Roughnecks enter eternally with fresh kegs; the thud of the mallet never ceases; the rude clamour of the bung-starter is as the rattle of departing time itself. Huge damsels in dirty aprons—retired kellnerinen, too bulky, even, for that trade of human battleships—go among the tables rescuing empty mässe. Each _mass_ returns to the shelf and begins another circuit of faucet, counter and table. A dame so fat that she must remain permanently at anchor—the venerable Constitution of this fleet!—bawls postcards and matches. A man in pinçe-nez, a decadent doctor of philosophy, sells pale German cigars at three for ten pfennigs. Here we are among the plain people. They believe in Karl Marx, blutwurst and the Hofbräuhaus. They speak a German that is half speech and half grunt. One passes them to windward and enters the yard.

A brighter scene. A cleaner, greener land. In the centre a circular fountain; on four sides the mediæval gables of the old beerhouse; here and there a barrel on end, to serve as table. The yard is most gay on a Sunday morning, when thousands stop on their way to church—not only Socialists and servant girls, remember, but also solemn gentlemen in plug hats and frock coats, students in their polychrome caps and in all the glory of their astounding duelling scars, citizens' wives in holiday finery. The fountain is a great place for gossip. One rests one's _mass_ on the stone coping and engages one's nearest neighbour. He has a cousin who is brewmaster of the largest brewery in Zanesville, Ohio. Is it true that all the policemen in America are convicts? That some of the skyscrapers have more than twenty stories? What a country! And those millionaire Socialists! Imagine a rich man denouncing riches! And then, "Grüss' Gott!"—and the pots clink. A kindly, hospitable, tolerant folk, these Bavarians! "Grüss' Gott!"—"the compliments of God." What other land has such a greeting for strangers?

On May day all Munich goes to the Hofbräuhaus to "prove" the new bock. I was there last May in company with a Virginian weighing 190 pounds. He wept with joy when he smelled that heavenly brew. It had the coppery glint of old Falernian, the pungent bouquet of good port, the acrid grip of English ale, and the bubble and bounce of good champagne. A beer to drink reverently and silently, as if in the presence of something transcendental, ineffable—but not too slowly, for the supply is limited! One year it ran out in thirty hours and there were riots from the Max-Joseph-Platz to the Isar. But last May day there was enough and to spare—enough, at all events, to last until the Virginian and I gave up, at high noon of May 3. The Virginian went to bed at the Bayerischer Hof at 12:30, leaving a call for 4 P.M. of May 5.

Ah, the Hofbräuhaus! A massive and majestic shrine, the Parthenon of beer drinking, seductive to virtuosi, fascinating to the connoisseur, but a bit too strenuous, a trifle too cruel, perhaps, for the dilettante. The Müncheners love it as hillmen love the hills. There every one of them returns, soon or late. There he takes his children, to teach them his hereditary art. There he takes his old grandfather, to say farewell to the world. There, when he has passed out himself, his pallbearers in their gauds of grief will stop to refresh themselves, and to praise him in speech and song, and to weep unashamed for the loss of so gemüthlich a fellow.

But, as I have said, the Hofbräuhaus is no playroom for amateurs. My advice to you, if you would sip the cream of Munich and leave the hot acids and lye, is that you have yourself hauled forthwith to the Hoftheatre Café, and that you there tackle a modest seidel of Spatenbräu—first one, and then another, and so on until you master the science.

And all that I ask in payment for that tip—the most valuable, perhaps, you have ever got from a book—is that you make polite inquiry of the Herr Wirt regarding Fräulein Sophie, and that you present to her, when she comes tripping to your table, the respects and compliments of one who forgets not her cerulean eyes, her swanlike glide, her Mona Lisa smile and her leucemic and superbly manicured hands!