CHAPTER X.

ACTORS AND EVENTS IN MEXICAN HISTORY.

Doubtless they also derived both stimulus and encouragement from the assured success of the American Republic, and gladly risked their lives in the hope of a like glorious consummation.

A better grounded or more righteous cause never existed than that of Mexico against the tyranny and usurpation of the Spaniards, who filled every place of power and emolument in the government to the exclusion of the Creoles and native population.

This state of affairs was long accepted as inevitable; but the idea of the divine right of kings and the immutability of established order received a rude shock when Napoleon overturned so many of the sovereignties of Europe, and among them that of Spain. Grand possibilities opened then before the vision of the foremost few, and these animated by the purest patriotism, unavoidably joined forces with men who sought only personal aggrandizement and the opportunities for place and power.

The result of the coalition of such conflicting elements may be read in the rapid succession of events, one military leader succeeding another, and, fired by jealousy and the dread of rivalry, summarily disposing of his predecessor. The popular idol of to-day may tomorrow be a victim to his own superiority, as envy, like death, loves a shining mark. His place in history cannot be augured from his fate at the hands of his countrymen. Time avenges all such, and many who were executed as traitors are now revered as martyrs, their dust the choicest treasure of the Grand Cathedral and San Fernando. The strife in which they lived is past; the passions to which they were sacrificed are stilled forever, and only their great deeds survive. They live in the hearts of their countrymen, and in every part of the republic their memorials are to be found in the forms of mural tablet or shaft.

The facilities now offered for travel in Mexico place within the reach of all who desire it, the privilege of visiting in person the historic places mentioned in this connection; and at almost every turn of the railway the eye may rest upon some evidence of a sanguinary contest or memorial of stirring event.

It was my pleasure and privilege to make pilgrimages to many of these places, and often while gazing upon shaft or cross my heart has been thrilled as I recalled the unparalleled struggles of the Mexican people for liberty.

"HIDALGO, THE WASHINGTON OF MEXICO."

Let us turn for a moment to the first scene in the grand drama for liberty.

The hour is midnight. The inhabitants are wrapped in a calm and delightful repose. The gray-headed veteran and the child with golden curls—youth and innocence, old age and infirmity—are alike in profound slumber, in blissful unconsciousness of the coming storm. It is in the unpretentious town of Dolores—suggestive name! The streets are quiet, but a glance toward the little church, henceforward to become in verity the Mexican Faneuil Hall and cradle of liberty, reveals dimly the outlines of men moving stealthily about in the gloom. They gather at length in a group around a central figure arrayed in priestly garb, a slender form telling of abstinence. See his eyes beaming dove-like gentleness and benediction! See the warrior-soul slumbering in the meek priest! See those eyes, once filled with woman-like gentleness, transformed to balls of fire that burn into the hearts of men, enthusing them with his own terrible thoughts! The eagle-glances that pierce the semi-darkness blaze into the dusky countenances of his followers! He waves his thin white hands, so oft engaged in supplication and in eloquent gesture, aiding his sacred oratory, as in words that burn he denounces the oppressor. The priest is a warrior now; the hand that has been so often raised in gentle benediction now strikes in wild gesture as though it held a sword. It would have blessed—it is now ready to smite!

Thus stood the venerable Miguel Hidalgo on the night of the 15th of September, 1810, as in animated tones he addressed his Indian allies, concluding with the exhilarating cry, "VIVA NUESTRA SEÑORA DE GUADALUPE!" "VIVA LA INDEPENDENCIA!" The banner of revolt is raised above their heads; he makes the sign of the cross, murmurs a prayer, and the humble cura of Dolores moves down the narrow street in front of his bronze adherents, releasing captives.

THE PATRIOT HIDALGO.

Ere the morning sun shed his first beams on the streets of Dolores, the bells pealed forth melodiously at so early an hour as to cause surprise to all within hearing. Soon the residents of the town and people from the adjacent pueblos were seen gathering around the portals of the church they loved so well. The cura is there, but not to celebrate the mass on this Sunday morning; for the work of revolution has already begun. From the pulpit he addresses that Indian multitude as "My dear children," and urges them to rend asunder the despised yoke of tyranny and to reclaim the property and lands stolen from their ancestors. "To-day we must act! Will you, as patriots, defend your religion and "our rights?" "We will defend them," shouts the crowd. "Viva nuestra Señora de Guadalupe!" and "Death to the bad government Death to the Gachupines!" "Live, then, and follow your cura who has ever watched over your welfare," is the reply of Hidalgo.

The cura of Dolores has addressed his congregation for the last time; and though bravely and resolutely determined to meet the issue without faltering, the thought is a painful one. Heretofore he has warned them to flee from the wrath to come, administered the holy sacrament and signed them with the cross in baptism; henceforward, in this new crusade against oppression and usurpation, he is their leader to victory—or death!

Miguel Hidalgo y Costillo was the second son of his parents, who lived in the province of Guanajuato.

From his early youth he was a close student, and when still quite young he had attained considerable proficiency in philosophy, and also in his theological studies in the College of San Nicolas in Valladolid. He received his degree of bachelor of theology at the capital, and was appointed successively to the curacy of two wealthy parishes in the diocese of Valladolid. The death of his brother was the means of his appointment as cura of Dolores, which gave him a salary of about twelve thousand dollars a year. He became a scientist, philosopher, and political economist, and was, besides, a linguist of high order. He invested his means in various ways; grew silkworms, planted grape-vines, put into successful operation a porcelain factory, and many other industries for the advancement of the people about him.

When the sphere of his knowledge is considered, he is found to have possessed an amount of information far in advance of his contemporaries, while his social and conversational gifts were exceptionally fine.

Hidalgo was fifty-eight years old when he raised the grito, but he had been long maturing the plan that finally triumphed over all obstacles.

We now return to Dolores, where the disaffected had already swelled into a formidable insurgent force. From thence they proceeded to San Felipe, gathering reinforcements by the way. They next surprised San Miguel, arriving at dark. They were received enthusiastically by the population, and proceeded without bloodshed to arrest the Spaniards; Allende, who was Hidalgo's chief support, and a brave officer, assuring them that no harm should come to them. A cheer was raised for independence, the colonel taken prisoner, and a thousand royalist troops added to the insurgent army. Here they procured the picture of the Virgin Guadalupe, which was transferred to their banner to lead them to victory.

They next advanced on Guanajuato, a city of seventy thousand inhabitants, the capital of the province, and the emporium of the Spanish treasures. Only thirty miles from the starting-point at Dolores, but in this short distance, the gentle zephyr of insurrection had become a perfect hurricane of revolution, and though the arms of the insurgents were so rude and miscellaneous in character, consisting of clubs, stones, machetes, arrows, lances and heavy swords, they did not hesitate to oppose themselves to the trained and armed Spanish garrison, and were victorious through enthusiasm and force of numbers.

Here Hidalgo remained for ten days, during which he proclaimed the independence of Mexico, and had himself elected Captain-General of America and Commander-in-chief of the army. The treasure, said to have amounted to five million dollars, provided him with the sinews of war.

We next see him at Valladolid, carrying all before him with the same violence and excessive severity as at Guanajuato. About this time he was joined by Morelos, also a priest, and a former pupil at San Nicolas, where Hidalgo had been regent. He had heard of the revolution, and in October hastened to ascertain the truth concerning it from Hidalgo. He traveled a long distance before overtaking him, but when assured that his sole aim was the independence of Mexico, full of patriotism and reverence for his old teacher, Morelos tendered his services, and received a verbal commission to organize an army and arouse interest in the southwest. This was their last meeting. The grand old college of San Nicolas had nurtured them both, and given an impetus to their endowments which would render both famous.

After the departure of Morelos, Hidalgo proceeded toward the capital, then under the command of the viceroy Venegas. With his large army of undisciplined Indians he began the march, and reached Monte las Cruces on the 30th of the month, and there encountered the Spanish forces, commanded by Truxillo and Iturbide. Here for the first time the raw recruits of Hidalgo came in contact with cannon. It is said that the Indians, in their frenzy, rushed forward and clapped their straw hats over the muzzles of the guns, hoping to evade the death-dealing missiles.

In this engagement, Hidalgo, though victorious, lost heavily. He then went within sight of the city, but declined to enter, though urged by Allende to do so. The victory of Las Cruces had been so dearly bought that another such would have been certain ruin.

Although at this time Hidalgo had cannon captured from the enemy, and his forces were in a more soldierly condition than ever before, nevertheless at the bridge of Calderon he was defeated by General Calleja. He then determined to retreat to the north, and with his best officers and several thousand men reached Saltillo in January, 1811. Leaving Rayon in command, he concluded to hasten to the United States to purchase military equipments with which to cope successfully with the efficient Spanish troops. He reached the Texas boundary with a large sum of money, when he was betrayed by Elizondo,[1] a former friend and compatriot, and taken a prisoner to the city of Chihuahua.

The triumphs of his brief career were as marvelous as his defeat was signal and irretrievable. Henceforward the floor of his prison cell must be the theater for the closing scenes of his eventful life. No hope of escape could penetrate those low, gray, pitiless walls! Defeat and captivity have transformed him, and he turns once more to his early vocation. The intrepid warrior is again the gentle priest! The eagle glance which enthused the hearts of his countrymen is once more softened in dove-like gentleness and benediction! The hand that smote is now raised in supplication as he implores Divine support and guidance. As he paces to and fro, he surveys the bloody path over which he led his victorious army, and while the retrospect discloses ghastly horrors, he pleads, in extenuation, grim necessity; but his undaunted spirit glows afresh as he recalls his glorious successes. He has opened the path to freedom, and the grito of Dolores will not cease to reverberate over the mountains and plains of Mexico until the work of liberation, begun by him and his compatriots, is completed.

In the long trial that followed, even the chains and shackles could not detract from the dignity and patience that characterized him.

On the 27th of July Dr. Valentine, as delegated by Bishop Olivares of Durango, pronounced the sentence by which Hidalgo was degraded from the priesthood. On the 29th he was summoned before the ecclesiastical tribunal, clad in clerical garb, and relieved of his fetters for the first time since his incarceration. He was then arrayed in the vestments of his holy office. While on his knees before the representative of the bishop, he listened to the explanation of the causes which led to this painful and humiliating scene. He was then stripped of his sacerdotal garments, and turned over to the civil authorities, after which he was again shackled and taken to his cell.

Ere the first streak of dawn, on July 31, 1811, Hidalgo was summoned to prepare for the closing scene. With the utmost serenity he partook of his last breakfast. He then declared his readiness to go with the guards, and assured them of his forgiveness. So heavily ironed that he could scarcely walk, his courage and fortitude did not for an instant fail him. He even remembered and asked for some sweets left under his pillow, and divided them among the soldiers. The sun had not yet risen and orders had been given that his head should not be mutilated, so he calmly placed his hand over his heart, as a guide for their aim. A platoon fired, wounding only his hand; Hidalgo remained motionless, but continued in prayer. Another volley severed the cords that held him to his seat, and he fell, though still breathing. Life was only extinguished when the soldiers had fired three more volleys near his breast, the veneration in which he was held doubtless interfering with the accuracy of their aim. Heroic to the last, thus died Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, and the fame of the Washington of Mexico, as he is called, grows brighter with succeeding generations.

Allende, Jimenez, Aldama, and Santa Maria had met the deaths of martyrs to the cause of liberty on June 26. The next day Chico and three others were shot, all meeting their death bravely, though forced to kneel like traitors and receive the fire of the musketry in their backs. Those who were priests were first stripped of their sacerdotal robes; then, after death, each one was dressed in the habit of his order and laid away with becoming respect. The heads of Hidalgo, Allende, Jimenez, and Aldama were placed in the four angles of the public storehouse in Guanajuato. Their bodies, however, were deposited in the chapel of the Franciscans, where they remained until 1823, when Congress ordered them, with their heads, to be placed in the cathedral at the capital with all the honors a grateful country could bestow.

JOSÉ MARIA MORELOS.

The death of Hidalgo left the leadership to Morelos, then operating in the southwest, whose superior genius designated him as a fitting successor. Posterity delights in knowing the birthplace of distinguished men, but on this point authorities differ with regard to Morelos. Some claim Valladolid, others Apatanzingan; but from his having spent a great part of his early youth in and near the former city, it is generally conceded to be the place of his nativity. His youth and early manhood were passed in hardy outdoor occupation, and although he was studious and ambitious, it was not until the age of thirty-two that he entered the college of San Nicolas, where he studied philosophy under Hidalgo, and, in accordance with his inclination, prepared for the priesthood. He became cura of different small towns near by, and his frugal habits enabled him at a later period to purchase a plain home in Valladolid.

JOSÉ MARIA MORELOS.

At the time of becoming a soldier Morelos was forty-five years old. On receiving his commission from Hidalgo he went to his curacy and there collected twenty-five trustworthy men, whom he armed with muskets, and began the march to the southwest. I have looked on much of that barren territory of several hundred miles, and wondered how in those perilous times he could have traversed it safely with his little band. At the various towns and hamlets, however, he received reinforcements, and sometimes whole militia companies seceded to him; but these were undrilled and unarmed. With this crude material and humble beginning Morelos inaugurated a thorough and systematic course of instruction in military tactics; so that in less than two months he had not only a well-drilled force of two thousand men, but had also inspired them with much of his own ardor and patriotism. He believed more in a small force with efficiency than in large numbers without discipline. His army continued to increase, and one victory led to another; he often took by surprise Spanish garrisons, imprisoning their leaders, and inducing the troops to unite with him. With this army he contended again and again successfully with the first commanders of the time and the country.

Indeed, the tide of events had so favored him that he naturally felt that the great cause of independence as assured. This was accentuated when, in the latter part of 1811, he was joined by Mariano Matamoros, another Indian priest, who, from the evident force of his character, would lend valuable aid to the great work. Morelos made him a colonel, and together they waged the war more vigorously than ever. If one considers the previous lives of these men, the genius they displayed must appear the more extraordinary. Their special talent was latent until it burst forth in those brilliant actions which startled the world. The military ability of Morelos elicited encomiums from one of the greatest captains of the age— Wellington; while Matamoros is described by Alaman as the most active and successful leader of the insurrection.

The first great event after Matamoros joined Morelos, occurred at Cuantla, where the latter had intrenched himself. Here General Calleja, in command of the royalist forces, being repulsed with heavy loss, determined to besiege the town. For this purpose a second Spanish force was sent out, and the siege was continued for nearly three months without reducing their defenses or diminishing the ardor and resolution of the patriots. Famine attacked them, and they were driven to the necessity of eating worm-eaten hides; but capitulation meant certain death, despite the offers of pardon made by the viceroy. All now seemed favorable for Calleja to capture the whole army, but notwithstanding his military prowess and reputation, with an ample supply of men and munitions of war, the Indian priest completely outwitted him. With masterly strategy Morelos withdrew from the town at night, and had been gone two hours before Calleja knew of his departure.

In September, 1813, Morelos called the first Congress at Chilpanzingo, the first act of which confirmed his title of Generalissimo, and a month later independence was declared.

It is not possible in this brief sketch to chronicle or enumerate his brilliant victories, in many of which he was aided by such chiefs as Matamoros, Galeana, the Bravos, Guadalupe Victoria, and Guerrero, most of whom figured afterward in the history of the country.

The city of Valladolid was a desirable point for the head-quarters of either army, being in the center of a wealthy and populous country. Morelos approached its confines, and stretched his infantry in a line in front of the city, while the cavalry occupied the hill of Santa Maria. Here it was that he met with an overwhelming defeat at the hands of Colonel Iturbide, from which he never recovered. Soon after, he lost his chief support by the capture of Matamoros, who was executed on February 3d following, in the public square of Valladolid, now called Morelia in honor of Morelos. From this time Morelos met with a succession of defeats and reverses until November 16, 1815, when he was taken prisoner, contending with characteristic bravery against an overwhelming force. He was carried to the capital, tried, and degraded from the ranks of the clergy, the bishop shedding tears during this last ceremony. He was then conveyed to San Cristobal, a village north of the lake, where the closing scene was to be enacted. Having said the last prayer, Morelos himself bandaged his eyes, and was led forth bound, and dragging his shackles. He complied with the order to kneel, murmuring calmly, "Lord, thou knowest if I have done well: if ill, I implore thy infinite mercy." "The next moment he fell, shot in the back, passing, through a traitor's death, into the sphere of patriot-martyr and hero immortal."

Among the many historic places that I visited, none interested me more than the house of Morelos in Morelia. In the drawing room I saw a finely executed portrait, placed there by the Junta Patriotica (Patriotic Club) in 1858. In this the expression of the face shows that blending of firmness, energy, frankness, and magnetism, which distinguished him, as well as the humor and gravity of his character, and other evidences of the genius of this remarkable man.

In the same room there hangs a frame containing a piece of the silk handkerchief which served to blindfold him before his execution at San Cristobal. At the bottom of the frame I read with pathetic interest these lines:

"This is the venerated relic,

The mournful bandage with which the tyrant

Hid the gaze of Morelos,

When the martyr of the Mexican people

Offered to his beloved country

His precious life as a sacrifice."

In front of the house is a commemorative tablet with this inscription:

"Illustrious Morelos! Immortal hero!

In this mansion which thy presence

once honored,

the grateful people of Morelia

salute you.

September 16, 1881."

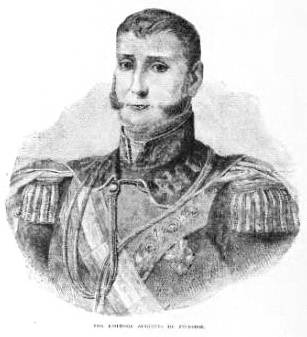

THE EMPEROR AUGUSTIN DE ITURBIDE.

THE EMPEROR AUGUSTIN DE ITURBIDE.

With feelings of more than ordinary interest I now turn to a contemplation of the life of Augustin de Iturbide. A peculiar chain of circumstances has associated his memory intimately with my own experiences and first days spent in Mexico, imparting a flavor of romantic interest to the details that follow.

It will be remembered that in exploring the immense old house in which I lived, my curiosity was richly rewarded by the discovery of the dust-covered and cobwebbed portrait of a beautiful woman. The soft eyes beamed on me from the painted canvas and the lips parted as if to speak. For two years it remained a mystery, but at length I ascertained that it was the portrait of Dona Ana, the beautiful wife of the Emperor Iturbide. More than two years passed, and I again returned to the land of the Aztecs; even now scarcely expecting to tread the soil which had nurtured both Iturbide and Doña Ana. But I had not only the pleasure of visiting at Morelia the identical houses in which they were born and reared, but also had the happiness of enjoying the acquaintance and friendship of, with one exception, the last living and only descendants of this handsome and distinguished pair. Augustin de Iturbide was fifteen when his father died, and the management of large estates devolved upon him.

His parents were of noble birth from Navarre, in old Spain; but Augustin was a native of Mexico, having been born at Morelia, September 27, 1783. He was married, at twenty-two, to the lovely Doña Ana Maria Huerte, also of a distinguished Spanish family. The same year in which his father died he joined a volunteer militia regiment in Morelia, and in 1805 entered the regular royalist army. His first experience of real military life was at the encampment at Jalapa, and in 1809 he gave material aid in crushing an embryo revolution at Morelia.

It is said that Hidalgo so highly appreciated the military talents displayed by Iturbide, that he offered him the position of lieutenant general before the first grito at Dolores. He declined this office and afterward, as colonel of the royal army, took part in many brilliant engagements, directed mostly against Morelos, the recognized successor of Hidalgo. The dashing young colonel, full of enthusiasm for the maintenance of established law and order, and the grave, clerical leader, had been nurtured among the same scenes.

Mention has been made of the defeat of Morelos by Iturbide at their native city. One of the most memorable events in the War of Independence was this encounter on the hills of Santa Maria, which skirt the city. Iturbide, who was second in command, sallied out with a small party to reconnoiter. Seeing defects in the position of the insurgents, where Matamoros had not taken due precautions in forming his line, he determined to seize the advantage, and with only three hundred and sixty cavalry, he dashed up the hill, accessible only by a steep path, where they were much exposed to cross-fires from the revolutionary army. He gave a loud cheer and rushed forward with his gallant band, creating dismay and confusion in the forces of Morelos. Not expecting such an attack, they were panic stricken, and, it being then after dark, believed that the entire royalist forces were upon them. A desperate battle ensued in the darkness of the night between the insurgents themselves, during which, after his gallant feat, and with captured banners and cannon, Iturbide retired in safety to the city, where he was received with enthusiastic demonstrations.

He received no promotion for that service, and Calleja said in after years, "Colonel Iturbide deserved more than I thought proper to give him." Soon after this brilliant action he became involved in dissensions with the military authorities, in consequence of which he retired to private life. But, smarting under the injustice that had been shown him, he conceived the idea of devoting his talents and services to the liberation of his country. The royalists evidently feared his marked abilities, should he again come upon the scene. A bishop, writing to Calleja, then viceroy, said of Iturbide, "that young man is full of ambition, and it would not surprise me if, in the course of time, he became the liberator of his country." Later events proved the correctness of the prediction.

The seed sown by Hidalgo was nurtured by Morelos, and, in due time, the whole grand scheme was harvested by the strong arm of Iturbide.

In the opinion of many writers, Morelia has given birth to the two most brilliant men in Spanish-America—Morelos and Iturbide.

For four years the cause of independence languished, though a guerrilla warfare was for a time kept up by Guerrero, Guadalupe Victoria, and others. In 1820 the troubles in Spain urged the Mexicans to a renewed effort for independence. Iturbide was again called upon by the viceroy, and given the command of the army of the southwest. In the distracted condition of the country, he knew the only safe and practicable plan would be to accept and then carry out his own design of freedom. Having a secret understanding with Guerrero, under pretense of an engagement, he soon afterward coalesced with that leader, taking his army with him. Thus it was, after all the struggle and sacrifice of years, independence was achieved by a bloodless victory. Iturbide then formulated "the plan of Iguala," an embodiment of his ideas of government, the first article of which declared the independence of Mexico.

It was well received at the time and accepted alike by the leaders and people. Soon after, on his thirty-eighth birthday, he entered the great capital triumphantly, surrounded by his aids, greeted with all the enthusiasm and manifestations of delight which the people were capable of displaying. Keys of gold were handed him with great ceremony on a silver salver. The country showered honors upon him, and on the night of May 18, 1822, he was made Emperor. In his address to the people he said, "If, Mexicans, I do not secure the happiness of the country; if at any time I forget my duties, let my sovereignty cease." He was crowned by the bishop, but with his own hands he placed the diadem on the brow of Doña Ana. An imperial household was established with imposing splendor, and money was coined in his image. He also instituted the Order of Guadalupe, a return to the days of chivalry, and designed to add to the prestige of the government. But "uneasy lies the head that wears a crown," and Iturbide was no exception to the truth of the apothegm. Only nine months from his coronation, pressure of circumstances and political changes forced him to abdicate. A sentence of exile was pronounced against him, and three months later, with his family, he was on his voyage to Italy.

To the soldier accustomed to a life of action, exile was intolerable; and possessed of an irresistible desire to return, within a year he made the homeward bound journey which proved fatal. A new and hostile government was in power, and Iturbide had lost his old influence. Not knowing the stern attitude of the government toward him, he landed July 14, 1824, at Soto la Marina, on the gulf coast; and scarcely had he touched his mother soil when he found himself a prisoner.

General Garza, the military commander, unwilling to act on his own responsibility, referred the matter to the State Congress of Tamaulipas, then in session at Padilla. With much show of respect and seeming confidence the ex-Emperor was conducted thither. He arrived late at night, hopeful and unsuspicious, having himself been placed by Garza in command of the escort which accompanied him. The next morning he was informed that he must prepare for death that afternoon. He remonstrated, asserting his innocence of any desire to disturb the existing order of things, and referring in proof of this to the presence of his family on shipboard. On finding the decree inexorable, he said, "Tell General Garza I am ready to die, and only request three days to prepare to leave this world as a Christian." But even this was denied him, and on the evening of July 19th, when the shadows began to gather and all nature was sinking to rest, they led him forth to execution.

With noble and commanding mien; with all his beauty and valor and social gifts; his smooth white brow, encircled with wavy light brown locks, now bared to meet the last decree of fate, the patriot stood undaunted, in Roman dignity. In clear tones he addressed these words to the soldiers: "Mexicans, in this last moment of my life I recommend to you the love of your country and the observances of our holy religion. I die for having come to aid you, and depart happy because I die among you. I die with honor, not as a traitor; that stain will not attach to my children and their descendants. Preserve order and be obedient to your commanders. From the bottom of my heart I forgive all my enemies." The officer came to bind his eyes, to which he objected, but being told that it was a necessary form, he unfalteringly bandaged his own eyes; then being requested to kneel, he did so, and the next instant received the fatal volley which terminated his brilliant and eventful life. His remains were buried in the dilapidated old church at Padilla, where they rested until 1838, when, with somewhat tardy justice and appreciation, an act of Congress was passed by which they were removed to the capital. They now rest in a stately tomb, in the great cathedral, with those of the noblest and best sons of Mexico. Here also lies Morelos, his old-time opponent. Cradled in the same city, their final resting-place is beneath the same dome.

On a tablet in the front wall of Iturbide's house I read the following inscription:

"On September 27, 1783.

Augustin de Iturbide,

The Liberator of Mexico,

Was born in this house.

Morelia, September 16, 1881."

The 16th of September, being the Mexican 4th of July, was a fitting time for Morelia to remember her two most distinguished sons.

The title of Liberator was conferred upon Iturbide in 1853, nearly thirty years after his death, and two years later the anniversary of his death was declared a public holiday. On that day a grand mass is celebrated in the cathedral of Mexico for the repose of his soul.

The ex-Emperor left a wife and eight children, but only the two youngest and Doña Ana accompanied him on his fateful return voyage, the others being left at school in England. The widow went first to New Orleans, afterward lived in Washington, then in Baltimore, finally taking up her permanent residence at Philadelphia, where in 1861 the once beautiful Dona Ana ended her eventful life, and now rests with several of her children in a vault of St. Mary's Church in that city.

The Princess Josefa, the only surviving child of the Emperor, resides in the City of Mexico. She remembers the coronation of her father and the pomp of court life which followed during his short reign. It was my pleasure to make her acquaintance, and I found her a woman of rare conversational gifts as well as great personal charm of manner. She is remarkably well preserved, and still shows a vigorous and cultivated intellect; is a fine linguist, and possesses a vast amount of historical information. But the one who connects the past with the present is Prince Angel de Iturbide. He attended the Jesuit College at Georgetown, D. C, where as a school-boy he met and loved Alice Green, the lovely daughter of Nathaniel Green, of that city. The wooing was persistent, and finally this charming and accomplished woman became his wife. In the course of time the laws which had banished Doña Ana and her family relented, and the Iturbides were allowed to return to Mexico.

Now comes an old, old story, but one which loses nothing by familiarity. In the checkered fortunes of Mexico, a prince of the house of Habsburg and an Austrian archduke was invited by the conservative party to preside over a new empire. Shortly after his arrival in Mexico he invited the Princess Josefa to take up her residence in the imperial household as a member of the family. She accepted, and was accorded the highest distinction by Maximilian and Carlotta.

Feeling the insecurity of his position and hoping to conciliate the discordant element among the Mexican people, Maximilian proposed to adopt the grandson of the Emperor Iturbide—son of Don Angel and Alice Green de Iturbide—and, should his empire succeed, the young Augustin, then three years old, would be heir to the throne. But a condition was made that his parents should leave Mexico without delay. The government then owed them a large sum of pension money, which it was agreed should be paid them in case of compliance.

The prospect was brilliant, and the parents thought that to some extent the arrangement would bring reparation for the wrongs inflicted on the child's grandfather, and so consented. The beautiful boy, with soft golden curls, gentle blue eyes and sweet baby prattle, became at once the idol of Maximilian and Carlotta. But the mother was bereft of her darling, and the compact was no sooner agreed to than regretted; she and her husband were to leave Mexico immediately, and the separation from her only child might be final and lasting. She reached Pueblo en route to Europe, but the anguish was too great, and she returned to the capital, hoping to regain the custody of her child. Marshal Bazaine received her with kindness, and she then addressed a heart-rending appeal to Maximilian. But under the guise of being taken to the palace she was decoyed from the city and forced to return to Pueblo. In Paris she met Carlotta, then on her ill-fated mission to procure aid for the fast crumbling empire. They had a memorable interview, and soon after, as Madame Iturbide herself told me, Carlotta received the death-blow to her hopes, and even when ordered to Italy by Napoleon, evidences of a tottering reason were manifest. Throughout these trying scenes Madame Iturbide maintained the dignity befitting a brave and high-bred woman.

When Maximilian felt his fate fast overtaking him, he sent Augustin to Havana, and at the same time communicated with Madame Iturbide, who joyfully met and received again to her tender heart her idolized boy. He is now a strikingly handsome young man, twenty-three years of age, six feet in height, and possessing wonderful physical strength. He has a finished education, both European and American, and is an accomplished linguist. He is also a lover of scientific knowledge, and exceptionally well read in history. Added to these natural and acquired advantages, he has artistic tastes, sketches from nature, and is skilled in music. In 1885 he was awarded the gold medal at the college at Georgetown, D. C, for the best oration delivered at the closing exercises. The hero of a romantic story, he appears unconscious of the notice he has attracted, and retains his modest demeanor and genial disposition, with the dignity and social graces which render his society delightful to all who come in contact with him. On his handsome country estate he leads a business life, and never seems happier than when there, dressed in his buckskin suit and silver-decked sombrero, and mingling freely among his employees, who adore him. The minutest detail of hacienda life claims his careful attention, showing a happy adaptability to circumstances.

The elegant residence of the Iturbides at the capital stands on the grand Pasco, immediately to the right of the statue of Carlos IV. Both there and at their hacienda of San Miguel Sesma, I have enjoyed their graceful hospitality and unrestricted friendship. On these occasions Madame Iturbide related many interesting incidents and reminiscences of her boy's early life. Among them, to me, one of the most amusing was the manner in which Augustin, when a little more than four years old, spoke his first English. His cousin, Plater Green, a few months older, fell from a tree, when Augustin ran to his parents, crying out: "Plater he up de tree—Plater he down de tree—Plater he no cry—Plater he one very man!" After this he would speak no more Spanish. Although brought up according to the Mexican custom of dependence on a servant, he early manifested the desire to throw off such bondage and prove his self-reliance. At the

MADAME ITURBIDE AND SON

age of fourteen, all alone, with $1,000 in his pocket, he sailed from Vera Cruz to New York, thence to Liverpool, and from there to Oscott College, near Birmingham, where he presented his letters to the president, and entered himself as a student. His life is still before him, and with his rich natural endowments and intellectual culture, his career will doubtless be worthy of his lineage and training.

The accompanying portraits furnish an excellent representation of mother and son.

Madame de Iturbide, herself, is one of the most remarkable women of her time. Beautiful in her youth, she is still strikingly handsome in face and figure. Of distinguished presence, queenly in manner and bearing, she impresses one as possessing in reserve the strength of will and purpose which sustained her in so many trying circumstances. All the elements of kindliness, courtesy, and dignity are combined in her, to which is added a personal magnetism which calls forth the warmest regard and devotion from all who enjoy the privilege of her friendship. During the thirty years since she went to Mexico, a bride, she has been a close observer of men and things. She is a living compendium of information on subjects of general interest, and is especially delightful in recounting those historical incidents which have come under her own observation.

In every transaction of business Madame Iturbide has proved herself equal to the occasion; and in the various lawsuits in which she has been engaged before the Mexican courts, she is said by competent authority to be as well versed in the jurisprudence of the country as the lawyers themselves. She is much attached to her Mexican friends, who warmly reciprocate the feeling, never losing an opportunity of showing their devotion to her. Americans everywhere may take pride in the fact that she is their countrywoman.

VINCENTE GUERRERO.

My interest in the history of Mexican independence was deepened by meeting and associating with many of the descendants of the statesmen and patriots who bore a conspicuous part in those thrilling scenes. All who are linked by lineage or ties of consanguinity to the heroes of the revolution, preserve sacredly every reminder and relic of their progenitors. Amid such surroundings, my desire for information was stimulated, and the impressions then received remain among the choicest treasures of memory garnered during my sojourn in old Mexico.

Vicente Guerrero was one of the leading spirits of the revolutionary period, and is revered in the history of his country as a man of unyielding patriotism, strict integrity, and stanch loyalty to its cause. After the death of Morelos, the germs of independence were kept alive and nurtured by Guerrero, who operated in the southwest, and was the most conspicuous figure among the insurgents when joined by Iturbide.

In the conflicts which have been waged on Mexican soil, guerrilla warfare has always borne a leading part, the inaccessible mountain fastnesses yielding immunity from danger of pursuit. This was the method pursued by the leaders after the fall of Hidalgo, Morelos, and Matamoras. When at last independence was achieved, Guerrero took an active part in every important movement until his death

He was the third president of the republic, and had served only a short time when he was deposed by Bustamente, then vice-president. He retired to his country estate, Tierre Colorado, in the vicinity of Tixtla; but being informed of a plot against his life, he left there and joined Alvarez, then in revolt against the government which had succeeded that of Guerrero. Fearing his influence, his death was determined on, and when, despite the warnings of Alvarez, he went to Acapulco, the opportunity came to carry out the nefarious plot. A Genoese named Picaluga owned a vessel then in the port of Acapulco, called the "Colombo." Knowing the desire of the parties in power to get rid of Guerrero, he made a compact with Minister Facio to decoy Guerrero on shipboard, and, for the sum of $50,000, to deliver him over to his enemies. This was accomplished by Picaluga inviting Guerrero to breakfast with him on board, and on rising from the table he caused him to be seized and shackled and conveyed to Guatulco, where the trial for his life soon began. A long list of crimes was brought against him, any one of which, to a man of Guerrero's integrity and patriotism, would have been impossible. After this show of justice, he was sentenced to be shot, and forced to listen to the reading of his sentence on his knees. On February 14, 1831, he was executed at Cuilapa, which later avenged the wrong by changing its name to Ciudad Guerrero.

A strong feature, consequent on the taking off of these heroes, was the quick rebound of public opinion. They were required to receive sentence kneeling, and not infrequently further humiliated by being shot in the back as traitors; but scarcely were they dead ere another party arose to avenge them; and in due time the nation issued its decree that their remains should be removed to a more honored spot, and laid away with imposing ceremonies.

The historian Alaman, whose work on Mexican independence is perhaps the most important that has been published, was a member of the cabinet under Bustamente when Guerrero was tried and executed. After the downfall of that administration, the whole ignoble proceeding was looked upon as downright murder by the succeeding government, and three members of the late cabinet, Alaman, Espinosa, and Facio, were impeached.

But it was thought that the last named was almost wholly responsible, as he had entered into the moneyed bargain with the treacherous Picaluga. The trial was postponed from time to time, until at length the cause was regarded as a party affair. Alaman was finally acquitted, his suavity and finished education no doubt assisting him in his defense. Facio went to Europe, and never again mingled in politics. Picaluga, the Genoese, was sentenced by his government to death, and mulcted in heavy damages; but as he could not be found, he escaped punishment. Gonzales, who received the hapless Guerrero at Guatulco, died miserably, a slow, torturous death.

Many tributes to the public and private virtues of Guerrero may be found in various places; and his name is perpetuated in that of one of the States of the Republic. It was said of him that "his modesty overshadowed his intelligence to the extent of not allowing him to enjoy the fruits of his services as his talents deserved."

Guerrero left a wife and one child, a daughter, who became the wife of Mariano Riva Palacio, afterward one of the most distinguished lawyers and public men of his time. Their son is General Vicente Riva Palacio, so often mentioned in these chapters.

I would like to dwell at length on the Bravos—Leonardo, the father, and Nicolas, the son. They loved their country with exalted patriotism, and devoted their lives to its liberation. Nicolas is spoken of by historians as one of the noblest specimens of manhood that the times produced. They were no less attached to each other than to their country.

After the battle of Cuantla, the father was taken prisoner, tried, and condemned to be shot. Venegas, the viceroy, so highly appreciated his abilities that he offered Bravo his life if he would induce his brothers and Nicolas to join the royalists. But liberty was his watchword; he scorned the offer, and paid the forfeit. A number of Spanish prisoners had been offered in exchange for him, but the viceroy, appreciating the value of a Bravo, had declined in his turn.

The grief of Nicolas for his father was deep and lasting; but even under this great sorrow his magnanimity shines forth grandly. He had then in his camp, as prisoners, three hundred Spaniards, many of them wealthy and influential men. His power over them was absolute; and had he taken their lives in retaliation for his beloved father's death, perhaps justice and the usages of war would have said,

"Well done!" But hear his noble words to them:

"Your lives are forfeit. Your master, Spain's minion, has murdered my father; murdered him in cold blood for choosing Mexico and liberty before Spain and her tyrannies. Some of you are fathers, and may imagine what my father felt in being thrust from the world without one farewell word from his son,—ay! and your sons may feel a portion of that anguish of soul which fills my breast, as thoughts arise of my father's wrongs and cruel death.

"And what a master is this you serve! For one life, my poor father's, he might have saved you all, and would not. So deadly is his hate, that he would sacrifice three hundred of his friends rather than forego this one sweet morsel of vengeance. Even I, who am no viceroy, have three hundred lives for my father's. But there is yet a nobler revenge than all. Go! You are free! Go, find your vile master, and henceforth serve him, if you can!"

In gratitude to him for sparing their lives, the soldiers, with tears in their eyes, offered their services in his cause, and were faithful to the last. General Bravo afterward bore a conspicuous part in the history of his liberated country. He lived to take part in the American war, his last military service being at the defense of Chapultepec and Molino del Rey. He died in 1854, at the age of sixty-eight, beloved and admired by all who knew him.

Equal in luster are the lives of other leading heroes of independence, whose deeds might shine in the bright galaxy of a Plutarch. Guadalupe Victoria was one of these immortal and brave spirits the record of whose career resembles more a fabled romance than a veritable history of real life. When the power of Spain seemed re-established, Victoria retired to the mountains, where he was hunted like a wild beast by order of the viceroy, at one time a thousand soldiers being employed in the search. A report of his death gave him a respite, and he lived alone in secluded and inaccessible fastnesses, without seeing a human being for two years and a half, until news was brought to him of the revolution of 1821, when he hastened to join Iturbide. He became first president of the republic, and, although every opportunity for peculation and private gain was afforded him, remained so poor that he was buried at the public expense.

GENERAL SANTA ANNA.

I congratulated myself upon an opportunity of visiting and becoming acquainted with the daughter of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, the Señora Guadalupe de Santa Anna de Castro. I found her an agreeable conversationalist, with pleasing manners and a happy faculty for entertaining. Her son was present, and during my travels in Mexico I have met few young men of more sprightliness and intelligence. He is about twenty-five, has a finely shaped head, blue eyes and fair complexion, resembling his mother, while his bearing is graceful and dignified. He speaks English fluently, having been secretary of the Mexican Legation at Washington. Let me whisper to my young countrywomen that Augustin de Castro is unmarried and greatly admires American young ladies. With manifest pride he showed me his gallery of American beauties.

Señora Castro, with a kindly appreciation of my curiosity, displayed some of the magnificent clothing worn by her father. The coat was gorgeous, with the national ensign embroidered with gold. A blue satin dressing-gown, with cords and tassels of gold, was decorated in the same way. Most interesting, however, was his mantle of the Order of Guadalupe which he had re-established. It was of blue satin lined with white moire-antique, and must have swept the floor for at least three yards. There was an imposing life-sized portrait of Santa Anna, on horseback, reviewing the troops on the pasco before Chapultepec. It was taken in one of the later terms of his presidency. The second wife of General Santa Anna was very young when married. It is said that she had in her possession a valuable autobiography of her husband, which the family endeavored in vain to procure from her for publication. It is, presumably, a vindication of his career, and now, since the death of Madame Santa Anna, it will likely be obtained.

In her sprightly way Señora Castro related to me particulars of her family, which consists of two daughters and her son Augustin. Knowing it to be customary for married children to live in the house with parents, I innocently asked if her married daughters lived with her. Quickly she replied that "sons-in-law make poetry about their mothers-in-law when out of their houses; if in them, it was not possible to predict what their utterances might be." Their elegant home stands on the first square to the left in going from the Alameda to the Zocalo.

(From an Oil Portrait.)

The name of Santa Anna is more familiar to Americans, and particularly to Texans, than that of any other Mexican. With it is associated the story of the Alamo, the massacre of Goliad, and the triumph of General Sam Houston at San Jacinto.

When only twenty-three years old, Santa Anna entered the arena of politics by disrupting the empire established by Iturbide, and the career thus begun was consistently carried out. At an early age he had so mastered the arcana of scheming and revolution as to reflect credit on a veteran in the cause, demolishing and creating sovereignties, often grasping victory from defeat, and gathering strength when all seemed lost. He was five times president, and was the means of deposing, probably, twenty rulers. As a commander of men, his resources and ability were remarkable. After the most disastrous defeat he generally managed to retire from the scene still holding the confidence of his ragged, half-starved army, increasing it materially while on the move.

From 1822 to 1855 he was the most conspicuous figure in public life. If deposed, he withdrew to his beautiful hacienda of Manga de Clavo, near Jalapa.

MANGA DE CLAVO, THE HACIENDA OF SANTA ANNA.

If exiled, he went without remonstrance, confident that his lucky star would again lead him to the front, and with fertile brain every ready to plan a revolution or arrange a coup d'état. But it may be truly said that in either case he was punctual to respond whenever his country demanded his services.

When the war with the United States came on, Santa Anna had shortly before returned from exile. He at once took command of an army of 20,000 men. He first met with a heavy defeat by General Taylor at Buena Vista, then at Cerro Gordo by General Scott, and when he retreated to defend the capital, defeat still followed him, and Molino del Rey, Chapultepec, and the capital surrendered to General Scott. His last move, in the vain endeavor to retrieve his fortunes, was to besiege Puebla, when he was again defeated, this time by General Lane. After the treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, in 1848, Santa Anna sailed for Jamaica. During this last exile the condition of the country bordered on anarchy, and the need of a strong government was so imperative that in 1853 Santa Anna was recalled. He was enthusiastically received, and appointed president for one year, when a constituent congress should be called. But instead of the latter, he instigated a new revolution, by which he was declared president for life, with the title—well calculated to provoke a smile—of "Serene Highness." A despotic spirit was soon manifested, and the result was the revolution of Ayutla, led by General Alvarez, one of the heroes of the wars of independence. After this memorable event, a desperate struggle of two years ensued, when Santa Anna abdicated, and left for Havana, August 16, 1855. Afterward, being a man of leisure, he visited Venezuela, where he remained two years. He then retired to the island of St. Thomas, where he lived quietly, probably meriting his title of "Serene Highness" more than at any other time in his career.

He returned in the early part of the French intervention, pledging neutrality; but having issued a manifesto calculated to cause disturbance, was ordered by Marshal Bazaine to leave the country, which he did, retiring again to St. Thomas.

After the fall of Maximilian, he returned to Vera Cruz to find himself a prisoner under sentence of death. Though this was not carried out, he was required to leave Mexico forever. From this time until the death of Juarez, in 1872, he resided in the United States. He returned once more to his native land, aged, feeble, and broken in spirit and fortune, and died in the City of Mexico on June 21, 1876, aged eighty-four years. He was buried at the church of Guadalupe, only a few prominent individuals following the funeral corétge.

Not the least singular circumstance in the stormy and checkered life of this remarkable man is its ending. Having passed through every phase of danger, while so many of his contemporaries fell in battle, or met death on their knees, he bore a charmed life, and, surviving defeat and exile, returned to the scenes of his grandest triumphs, and breathed out his last days on his own soil surrounded by his family.

In the accompanying illustrations we see him first as president, covered with the insignia of his successes; and the later portrait presents him as he looked at the time of his death. The contrast is striking and mournful, telling of failure in a man possessing so many elements of greatness, who might have held the highest place in the hearts of his countrymen long after his physical frame had moldered into dust.

The signing of the Federal Chart in 1857 was one of the most important of all the memorable events in Mexican history. Its anniversary is wisely observed as a national holiday.

GENERAL SANTA ANNA.

Of the large number of signers, there remain only twenty-five survivors. Several of these are octogenarians, while others fill places of trust and importance in their country's service. Foremost and best known to us are Señor Ignacio Mariscal, at present Minister for Foreign Affairs: Señor Romero Rubio, Secretary of the Interior; General Ochoa; and the veteran statesman, politician, and soldier, Guillermo Prieto—all of the capital.

We now come to consider a few of the leading spirits of the war of reform which began to be prosecuted when Santa Anna stepped aside from the political arena.

BENITO JUAREZ.

Let us now take a pleasant stroll through the Alameda and along the great highway leading to Tacuba, until we come to the grand old church and pretty plasuella of San Fernando, and the Pantheon, bearing the same name. The little plaza is shaded by giant trees, fragrant with myriad flowers, carpeted with soft, green turf, and the air rendered sweet and delicious by the ripple of the sparkling fountain: a place for day-dreams, so quiet and redolent of the past. But, in pursuance of our object, we suddenly find ourselves within a broad, grated doorway, and the next moment a polite little old man, clad in domestic, comes forward, hat in hand, with a smile, and the question:

"What will you have?"

"We wish to see the monument to Juarez;" whereupon he leads the way, halting as we halt to read an inscription on this or that tomb or vault, and volubly relating the history of the occupants of this grand old burial-ground. He became so interesting at last, that I found myself desirous to know something of him, this plain, humble, polite old man. Without ceremony I asked:

"Tell me something of yourself."

"Muy bien, señora. You have heard of the battle of Chapultepec, between the Americans and Mexicans?"

"Yes!" I replied; "but what has that to do with you?"

He shook his head, as he recalled the scenes then enacted, and responded:

"I was the bugler on that awful day, and saw our dear old flag go down and the Americans take possession of that place, so sacred to every Mexican."

He then went on to relate the tragic and heart-rending incident of the death of the gallant forty-eight students, boys from fourteen to twenty, who had their swords wrested from their hands and died nobly in defense of their country. We listened to the old man's reminiscences as we passed the tombs of Zaragoza, Miramon, Mejia, and others; but welcomed the timely silence which fell on the party as we reached the tomb of Mexico's greatest statesman, patriot, and soldier, her Indian president, Benito Juarez. Here he lies, stretched out in majestic, marble dignity; so life-like, so realistic, as to cause a sudden thrill of awe in the beholder. It was a touching inspiration of Manuel Islas when he chiseled this sublime effigy, with the mourning figure of La Patria bending over it. Summer and winter this noble tomb is fragrant with floral offerings most gorgeous and beautiful, laid there by his grateful countrymen.

In striking contrast with the grandeur of his last resting-place was the early home of the Champion of Reform. I see it now, a simple adobe structure containing two or three rooms, without windows, their earthen floors cleanly swept, and with, perhaps, only one or two doors for the whole building. The roof was of either adobe or planks; if the latter, it was held in place by numerous stones, while climbing and clinging tenderly to the unsightly walls were tropical vines and plants which, in the profuse luxuriance of nature, covered the whole with their blossoms of gorgeous tints, finally disappearing over the housetop, and transforming the humble home into a bower of beauty. The inclosure was composed of the organ-cactus, standing like sentinels warding off all intruders.

The village of San Pablo Gueltaco reclines unevenly on a rocky spur of the Sierra Madre in the State of Oaxaca, whose shores are washed by the waters of the Pacific. The hamlet has its narrow, irregular streets, its forest trees, tropical flowers, and luscious fruits, and in the grateful shade stands the neat white church to which the devout, in undisguised simplicity and piety, repair at all hours of the day. The Enchanted Lake lies near, reflecting in its translucent depths the tropic growths surrounding it, and suggesting the romantic and shadowy traditions of the past.

Two hundred Indian aborigines constitute the entire population of San Pablo. They live by tilling the soil in the old-time honest way. The parents of Benito Juarez cultivated their few acres and tended their cattle with the rest, in happy equality. Amid these primitive surroundings the champion of Mexican independence and reform, on March 21, 1806, first saw the light. He never knew a mother's love, she having died at his birth, leaving him to the care of his grandmother and uncle. Here he lived until he was twelve years of age, and was so thoroughly an Indian that not one word of Spanish had ever passed his lips.

About this time he attracted the attention of a worthy citizen of Oaxaca, who took him into his service, and recognizing the boy's talents, determined to give him the best possible educational advantages. He placed him in the ecclesiastical seminary, with a view to the priesthood, but finding that profession repugnant to his tastes, within a year he threw off the robes and turned to the law. He entered the college of Oaxaca, where he pursued his legal studies, teaching at the same time. Here he graduated with honors, and in 1834 was admitted to the bar. During these years he distinguished himself in every branch of study, and his conduct was most exemplary.

He did not long pursue the practice of law, but devoted himself to political affairs. Quite early he began to study the welfare of his country, being deeply imbued with a sense of the importance of a radical change in affairs. The Conservatives imprisoned him for his outspoken utterances, but the effect was to add strength to his vigorous thought.

In 1842 he became chief justice of the Republic, which office he held for three years. He was made governor of his own State in 1847, and remained so until 1852, on every possible occasion introducing liberal measures and useful reforms. As a determined enemy to despotism, he was exiled by Santa Anna, when he took up his residence in New Orleans, where he lived for two years in great poverty. On the revolution of Ayutla, in 1855, from which event dates the law of reform, Juarez returned and joined with Alvarez, who commanded the revolutionary forces against Santa Anna. The success of the revolution made Alvarez president, and Juarez became minister of justice and religion. His first move was a bold one—the abolition of the special clerical and military courts, under which these two classes had enjoyed immunity from the general laws. Congress sanctioned the

TOMB OF JUAREZ, IN SAN FERNANDO.

whole, but a change of administration followed, when the new president, Comonfort, fearing the progressive liberalism of Juarez, appointed him governor of his own State.

The promulgation of the Federal Chart in 1857 made a decisive change in the political outlook. In this year Juarez was elevated to the office of justice of the supreme court—a position equivalent to that of vice-president of the United States. In 1858 he became president, but the strength of the reactionary party was such as to cause him to transfer the government from one point to another until he reached Vera Cruz. A strong defense was his recognition as president by the United States in 1859; but it was not until 1861 that he was enabled to establish his government at the capital, having defeated Miramon, who was at the head of the church party. The next year he was confirmed as president, and at once set about reorganizing the whole body politic. The suppression of religious orders, the confiscation of church property, and the suspension of the payments of foreign debts and national liabilities were the most prominent acts of his administration.

Mention has been made in another chapter of the wholesome effect of his vigorous measures, and the great work still goes on. Juarez seemed to have been born to redress the wrongs of the times, and events so shaped themselves in his stormy career as to develop the wonderful firmness and strength of his nature. After the issuance of his decree suspending the payment of national indebtedness, France, England, and Spain united to invade the country. The allied forces reached Vera Cruz; but Juarez having pledged himself that the interests of creditors should be protected, all withdrew except France. Under pretense of protecting its citizens, but really with a view to establishing a monarchy in which the interests of the church would be paramount, the French government sent an army of invasion, April, 1862, under General Forey, whose first movement was the capture of Puebla. Juarez, finding the capital insecure, retired to San Luis Potosi. In 1864, protected by French bayonets, Maximilian ascended his uncertain throne, while the government of the people, represented by Juarez, moved from one point to another until it finally rested at Paso del Norte.

While here. President Juarez was frequently invited to cross the river, and visit the American officers at Fort Bliss; but he always declined, fearing that such an act might be construed into an abandonment of his own beloved soil.

In June, 1866, he began his southward march. Over much of the same ground which he had traveled a fugitive, he now led his victorious army. In February, 1867, Marshal Bazaine, with his army, sailed for France, leaving Maximilian behind in a hostile country. The latter was entreated to leave, but his fate withheld him.

Juarez soon had possession of Queretaro, where Maximilian had concentrated his few remaining soldiers. The story of the execution of Miramon, Mejia, and Maximilian, on June 19, 1867, needs no repetition. For some time public opinion, especially outside the republic, censured the execution of these distinguished men; but in counting the cost of their venture, they must have anticipated death in case of failure. The memory of Juarez is undimmed by the shadow of aught that would detract from his glory. Had he never done another act save that of divorcing Church and State, his name should remain forever embalmed in the hearts of his people.

Although every opportunity to acquire wealth was afforded him in the various positions he held, the truth comes down to us that he died a poor man. His family relations were of the happiest nature, and in the society of wife and children he enjoyed relaxation from the cares of state and public affairs.

He was re-elected president in 1871, and, after so much storm and contest, he might have hoped to live out his days in undisturbed calm; but though physically strong, his nervous system gave way at last. He died on July 19, 1872, aged sixty-six years, revered and honored by his contemporaries and a shining example for future generations. The recumbent marble figure in San Fernando is but a faint tribute to his worth.

Among the many pleasant people of historic association whose acquaintance I made at Morelia, was the polite and accomplished son of Melchor Ocampo, who was a prominent figure in the early reform movement, and whose name is familiar to many of our own countrymen of that period. The young man gave us the life of his father, from which I have made a few touching extracts. The enthusiastic compiler, Eduardo Ruiz, properly dedicates the work to the students of San Nicolas, because, as he says, "the last thought of Ocampo, before his execution, was of the students, whom he called his sons." One of the choicest spirits of the time, and associated with Juarez in the reform agitation, was Don Melchor Ocampo, Governor of Michoacan. He had also been a cabinet minister under Alvarez, in 1855-56. Alike in his brilliant and studious youth, and in the dignity of his mature manhood, he devoted himself to the cause of emancipating his country from military despotism and from the tyranny of those retrograde ideas which had so long retarded her progress. He was a poet and a scholar, as well as a patriot, philanthropist, and statesman, and his pen and sword were alike consecrated to the service of his country. Like many of his contemporaries and fellow-workers in the field of reform, he did not live to enjoy the fruits of his labors; but who will therefore say his life was incomplete, or not fully rounded out?

His tragic death exemplified all the manly virtues of his life, and it is fitting to relate how grandly and calmly this Mexican hero died.

He had retired to his country place near Pomoca, where he sought a quiet interval from the cares of state, solaced by friendship and surrounded by his trees and flowers.

In the early morning of a day in May, 1861, a company of reactionary soldiers, with their captain, approached the house. They entered and arrested a gentleman whom they saw there, Don Entimio Lopez, under the belief that he was Ocampo. The soldiers were about to retire with their prisoner when Ocampo appeared on the scene. He had been in an inner room, and had just discovered the presence of the soldiers, and his friend's arrest. He approached the captain, asking, tranquilly:

"For whom are you looking?"

"Ocampo," was the reply.

"Well, I am Ocampo: release this gentleman; he is my guest."

Without giving him time to get even his hat, they marched off with him to Tepeji deJ Rio, where, on being presented to General Marquez, the cause of the proceeding was clear and the issue certain. This general had given orders that any one taken prisoner who had labored in the cause of reform, should be instantly shot. Ocampo proved his heroism in the trying hour of death. He slept calmly the night before his execution. The next morning, June 3, 1861, he was notified that his hour had come. Standing beneath the shade of a grand old tree, he leaned against its trunk; then asking for pen, ink, and paper, he wrote in a firm hand an addition to his last will and testament in behalf of his family, remembering also some orphan children, and adding a clause bequeathing his library to the Colegio de San Nicolas. Then placing his hands upon the tree, he raised his head as if in prayer, when the discharge of firearms added another to the long list of martyrs to the cause of liberty in Mexico.

In appreciation of his character and services, his native State has added his name, and is now known as Michoacan de Ocampo. His remains were taken to the capital, and, after lying in state in the national palace, were laid to rest in San Fernando, in the glorious companionship of his co-laborer in reform, Juarez.

Mexico has her hundreds of noble and heroic sons, many of whom have reached their three-score and ten years. They have served her in victory and defeat, and through her darkest hours have never swerved in their patriotic allegiance. Some of them now occupy exalted positions in diplomatic relations with foreign countries.

Among those who have grown gray in her service are Señor Navarro, for a quarter of a century Mexican consul at New York. He was a strong adherent of Juarez, and is a native of Morelia. Another is Señor J. Escobar, the venerable consul at El Paso, Texas, who has faced danger in all its forms, braved defeat time and again, but never lost his love of country. On one occasion at Chihuahua, during the French intervention, he was imprisoned and made to sweep the streets with the common prisoners of the town, for attempting, with others, to celebrate the 16th of September in honor of Hidalgo. The ladies and children turned out en masse and strewed flowers along his way as he performed his humiliating task. He has filled various responsible public offices, having been Secretary of Legation at Washington 1861-2-3, and was also sent to England during the war between the States as a confidential agent of his government. The pages of history have not recorded a more stirring event than the war between the United States and Mexico.

Benjamin Franklin wisely said, "There never was a bad peace nor a good war," and taking up these sentiments after the lapse of a century, Hubert Howe Bancroft says:[2] "If the injustice of all war was never before established, it was made clear by the contest between the two republics of North America. The saddest lesson to learn by citizens of the United States is, that the war they waged against their neighbor is a signal example of the employment of might against right, or force, to compel the surrender by Mexico of a portion of her territory and, therefore, a blot on her national honor." "The United States," he continues, "had an opportunity of displaying magnanimity to a weaker neighbor, aiding her in the experiment of developing republican institutions, instead of playing the part of bully."

In a severely caustic spirit he continues: "The United States could have secured peace by ceasing to assail the Mexicans, who were fighting only in self-defense; but the much desired peace they resolved so to secure by war that a bargain, which was nothing better than a barefaced robbery, should be secured. It was not magnanimity but policy which prompted Polk and his fellows to pay Mexico about twenty million dollars when she was at the conqueror's mercy. It gave among the nations, howsoever Almighty God regarded it, some shadow of right to stolen property.*** The total strength of the army employed by the United States in Mexico from April, 1846, to April, 1848, consisted of 54,243 infantry, 15,781 cavalry, 1,789 artillery, and 25,189 recruits; making a total of 96,995 men. The total number called out by the government exceeded 100,000 men. The number that actually served in Mexico exceeded 80,000 men, not all called out at the same time, but in successive periods. At the close of the war, according to the adjutant general's report, there were actually 40,000 in the field. *** The so-called improvements of warfare, in the opinion of men, justify the continuance of warfare on the ground that the destruction of life and the infliction of suffering have been undiminished by the new devices. God save the mark! Killing men is not a trade susceptible of improvement; the experiences of the Mexican war show that neither side dispensed with the horrors of ancient practices.

"The gain in territory by the United States was immense, comprising a surface of 650,000 square miles. From the mines alone it is computed that precious metals have been extracted to the extent of $3,500,000,000. Besides this, we must remember the vast wealth of Texas, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and Utah.

"The loss in money to Mexico will never be ascertained. *** And yet, unhappy as the results were for it, one must acknowledge that its honor was maintained. The treaty represents, indeed, its great misfortune, but does not involve perpetually ignominious stipulations, such as many another nation has submitted to at the will of the conqueror."

A bitter dose is this that Mr. Bancroft has prepared to go down to posterity as the history of that war. But in accepting his faithful research, and reluctantly admitting the truthfulness of his assertions, a part of the public, at least, will attribute his severe criticisms of President Polk to a wide difference of political opinion.

It is not the writer's intention to cast any reflections upon President Polk or his administration, or to arouse bitter feeling in the survivors of that struggle. No one more upholds the bravery and integrity of her countrymen. The war seemed to have been one of the exigencies of the times and our neighbors fit subjects for spoliation.

But did not Mr. Bancroft present his honest convictions, he would repudiate that boasted freedom of speech of which every American citizen is proud.

It is well, however, to have both sides of the question, and if this historian appears too severe to the average American mind, we have the writings of a sweet and gentle woman, which frankly take up the wrong-doings of her countrymen after the conquest of California. Let every American read for himself Helen Hunt Jackson's pathetic story of Ramona, and deplore the wrongs that were heaped upon the Temecula Indians, as well as other native races, who lived in California at and after the time of the conquest. How her generous nature revolted at the injustice of her own countrymen; and ere she closed her eyes in their last sleep, she presented her views in so eloquent a manner as to produce a deep and powerful impression throughout this great nation.

Her Century of Dishonor likewise unfolds a pitiable story of the course of our government towards the Mexican Indians. Her last words ever penned were the outpourings of her spirit in the form of a prayer to President Cleveland in behalf of the Indians. May it be good seed sown in good ground which shall come forth and produce abundantly in future generations!

Another thought is here suggested, which has already taken form in the minds of many eminent writers, such as David A. Wells, Joaquin Miller, Solomon Buckley Griffin, and numberless others, equally well known. The proposition is, that every banner, cannon, or other trophy captured during that unhappy contest be returned to Mexico. It would be but a just though tardy reparation of a great wrong.

If the matter were placed before Mrs. Cleveland, and the power given her to do as she in the goodness of her gentle heart and purity of purpose thought best, we are sure of one thing this Queen of Hearts would undoubtedly say: "Give them every one back; I want to see fitting justice done to these people."

For the benefit of those who have not looked into the causes of the Mexican war, especially for the younger generation who may not have had access to standard works on the subject, I will state that the bone of contention was the boundary line between Texas and Mexico, when the former was about to relinquish her claims as a republic and seek admission into the United States. The strip of country involved in the controversy was that lying between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, about 300 miles long and with an average width of 7S miles, equal altogether to 22,500 square miles. The Mexicans claimed the Nueces as the boundary, while the Americans claimed the Rio Grande.