Letters from England/The Biggest Samples Fair; or, The British Empire Exhibition

The Biggest Samples Fair; or, The British Empire Exhibition

I

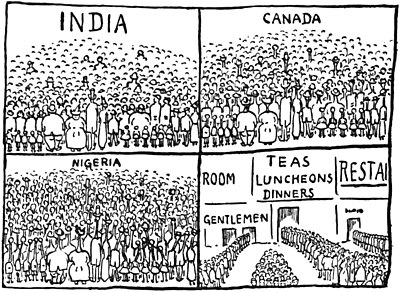

IF I am to tell you at the outset what there is most of at the Wembley Exhibition, then decidedly it is the people and the parties of school-children. I am all in favour of populousness, propagation, children, schools and teaching by object lesson, but I must confess that at times I should have liked to have a machine gun with me to cut my way through an agitated, pushing, rushing, trampling herd of boys with small round caps on their pates, or through a chain of girls holding hands so as not to get lost. From time to time, by dint of infinite patience, I managed to reach a stand. New Zealand apples were being sold, or rice-brooms from Australia were exhibited, or a billiard-table manufactured in the Bermudas. I even had the luck to behold a statue of the Prince of Wales, made of Canadian butter, and it filled me with regret that the majority of London monuments are not also made of butter. Whereupon I was again thrust forward by the stream of people and gave myself up to the view of the throat of a stout gentleman or of an old lady’s ear in front of me. However, I made no objection: what a crush there would be if in the Australian refrigerator section the florid throats of stout gentlemen were exhibited, or in the clay palace of Nigeria baskets containing the dried ears of old ladies.

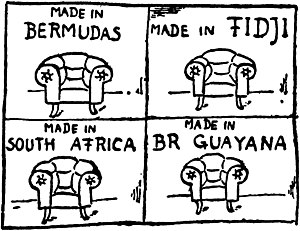

Powerlessly I abandon the intention of producing an illustrated guide to the Wembley Exhibition. How am I to portray this commercial cornucopia? It comprises stuffed fruit, dried plums, arm-chairs manufactured in Fiji, mountains of dammar and tin ore, festoons of legs of mutton, dried copra like gigantic bunions, pyramids of preserved foods, india-rubber lamp-shades, old English furniture from South Africa, Syrian currants, sugar-cane, walking-sticks and cheese.  And New Zealand brushes, sweetstuff from Hongkong, Malay oils. Australian perfumes, models of some tin mines or other, gramophones from Jamaica and mountain-ranges of butter from Canada. As you see, it is a regular tour round the world, or rather a trip through an overgrown bazaar. Never have I been at so huge a fair.

And New Zealand brushes, sweetstuff from Hongkong, Malay oils. Australian perfumes, models of some tin mines or other, gramophones from Jamaica and mountain-ranges of butter from Canada. As you see, it is a regular tour round the world, or rather a trip through an overgrown bazaar. Never have I been at so huge a fair.

The Palace of Engineering is magnificent; and the finest works of English plastic art are locomotives, ships, boilers, turbines, transformers, queer machines with two horns at the top, machines for all sorts of rotating, shaking and banging, monsters far more fantastic and infinitely more elegant than the primeval lizards in the Natural History Museum. I do not know what they are called and what they are used for, but they are superb, and sometimes a mere screw matrix (a hundred pounds in weight) is the highest pitch of formal perfection. Some machines are red like paprika, others massive and grey, some burnished with brass and others black and tremendous like a tomb, and it is odd that an age which has devised two pillars and seven steps in front of every house, should have composed in metal such inexhaustible wonders and beauties of forms and functions. And now, just imagine that this is crammed together on an area larger than the Vaclav Square, that it is larger than the Uffizi and the Vatican collections put together, that for the most part it rotates, hisses, grinds with oiled pistons, chatters with steel jaws, fatly sweats and glistens brassily: it is the mythic emblem of the metal age. The sole perfection which modern civilization attains is a mechanical one; machines are splendid and flawless, but the life which serves them or is served by them, is neither superb nor brilliant, nor more perfect nor more graceful; nor is the work of the machines perfect; only they, the machines, are like gods. And I may tell you that I discovered an actual idol in the Palace of Industry. It is a revolving invulnerable safe, a glossy armoured ball, which quietly revolves and revolves on a black altar. It is wonderful and a little uncanny.

Bear me homeward, Flying Scotsman, splendid hundred-and-fifty-ton locomotive; carry me across the seas. O white and glittering ship; there will I sit down on the rough field-edge where the wild thyme grows, and I will close my eyes, for I am of peasant blood and have been somewhat disturbed by what I have seen. This perfection of matter, from which no perfection of man is derived, these brilliant implements of a grievous and unredeemed life bewilder me. Beside you, Flying Scotsman, what would that blind beggar look like who sold me matches to-day? He was blind and corroded with scabies; he was a very bad and impaired machine; in fact, he was only a man.

II

Besides the machines, the exhibition at Wembley displays a twofold spectacle: raw materials and products. The raw materials are usually more attractive and interesting. An ingot of pure tin has something more perfect about it than an engraved and hammered tin dish; russet or fiery-grey timber somewhere from Guiana or Sarawak is decidedly more attractive than a finished billiard table, and stickily translucent raw rubber from Ceylon or Malaya is really far more beautiful and mysterious than rubber floor coverings or a rubber beef-steak; and I will not describe to you all the various African corn-grains, nuts from heaven knows where, berries, seeds, cores, fruits, kernels, bulbs, wheat-ears, poppy-heads, tubers, pods, piths and fibres and roots and leaves, things desiccated, floury, oily, and leafy in all colours and palpable qualities, the names of which, for the most part very beautiful, I have forgotten, and the use of which is somewhat of a riddle to me; I think that their final mission is to lubricate machines, to imitate flour or to anoint the suspicious-looking tarts in Lyons’ wholesale feeding establishments. From these flame-coloured, striped, magenta, dusky and metallically resonant timbers, of course, old English furniture is made, and not negro idols or temples or the thrones of black or brown kings. At the most only baskets or bags from bark, in which this abundance of British Imperial trade articles was conveyed here, tell their tale of the negro or Malay hands which inscribed them with the strange and beautiful technique of their manuscript. All the rest is a European product. But no, I must not lie—not all the rest. There are a few acknowledged exotic industries, as, for example, the wholesale manufacture of Buddhas, Chinese fans, Cashmere shawls or damascene blades, which the Europeans are fond of. And here are manufactured on a large scale Sakiamunis, aniline lacquers, Chinese porcelain for export, ivory elephants and ink-pots of serpentine or talc, engraved dishes, mother-of-pearl follies and other exotic manufactures guaranteed genuine. There is no popular native art; a Benin negro carves small figures from elephant-tusks as if he had proceeded from the Munich Academy, and if you give him a piece of wood, he will carve an easy-chair from it. Good gracious, he has evidently ceased to be a savage and has become—what? Yes, he has become an employee of civilized industry.

There are four hundred million coloured people in the British Empire, and the only trace of them at the British Empire Exhibition consists of a few advertisement supers, one or two yellow or brown huxters and a few old relics which have been brought here for curiosity and amusement.  And I do not know whether this is a terrible decadence of the coloured races or the terrible silence of the four hundred millions; nor do I know which of these two things would be the more dreadful. The British Empire Exhibition is huge and filled to overflowing; everything is here, including the stuffed lion and the extinct emu; only the spirit of the four hundred million is missing. It is an exhibition of English trade. It is a cross-section through that feeble stratum of European interests which have enwrapped the whole world, without troubling too much about what there is underneath. The Wembley Exhibition shows what four hundred million people are doing for Europe, and partly also what Europe is doing for them. There is not much of this even in the British Museum, the greatest colonial empire actually possesses no ethnographical museum. . . .

And I do not know whether this is a terrible decadence of the coloured races or the terrible silence of the four hundred millions; nor do I know which of these two things would be the more dreadful. The British Empire Exhibition is huge and filled to overflowing; everything is here, including the stuffed lion and the extinct emu; only the spirit of the four hundred million is missing. It is an exhibition of English trade. It is a cross-section through that feeble stratum of European interests which have enwrapped the whole world, without troubling too much about what there is underneath. The Wembley Exhibition shows what four hundred million people are doing for Europe, and partly also what Europe is doing for them. There is not much of this even in the British Museum, the greatest colonial empire actually possesses no ethnographical museum. . . .

But withdraw from me, evil thoughts: let me rather be pushed and thrust along by the stream of people from the apples of New Zealand to the cocoa-nuts of Guinea, from the tin of Singapore to the gold ores of South Africa; let me see the distant places and zones, the minerals and products of the earth, the relics of animals and people, all the things from which, in the end, crackling pound notes are stamped. Here is everything which can be turned into money, which can be bought and sold, from a handful of corn-grains to a saloon carriage, from a piece of coal to a set of blue fox furs. My soul, out of all these treasures of the world, what would you like to buy? Nothing, nothing whatever; I should like to be tiny, and to stand once more in old Prouza’s shop at Upice, to stare, goggle-eyed, at the black gingerbread, the pepper, the ginger, the vanilla and the laurel leaves, and to think to myself that these are all the treasures of the world and the scents of Arabia and all the spices of distant lands, to be amazed, to sniff and then to run off and read a novel by Jules Verne about strange, distant and rare regions. For I, foolish soul, used to have quite a wrong idea of them.