THE MYCENAEAN CITY

In the earlier excavations on the hill of Hissarlik the stately circuit wall and the buildings of the VI Stratum had not come to light. Shortly before Schliemann's death, in the year 1890, the first structure, with the vases of Mycenaean pattern found therein, was unearthed. This building (VI A), we may say, formed the starting point for completely laying bare the Mycenaean citadel. While on the southeast and northeast of the hill a part of the South Circuit Wall and several inner buildings remain buried under ruins and débris, yet the excavations enable us to form a satisfactory picture of the massive city wall, the huge towers, the gates, the terraces, and the dwellings of the ancient fortress.[1]

8. Masonry.[2]The VI City shows a marked difference in its style of masonry. Some portions of the walls are made of blocks carefully wrought and fitted together, without cement, so closely that the interstices are hardly visible; others are constructed of stones, only the outside of which is polished, and the interstices filled with rubble and clay; again, in several places, the stones are unwrought, as in the so-called Cyclopean masonry.

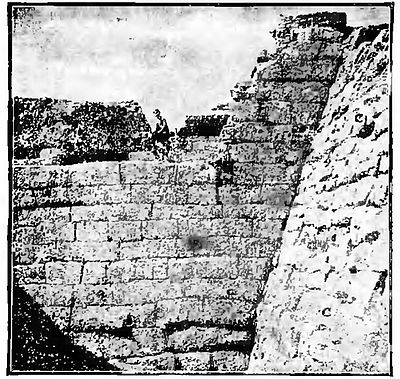

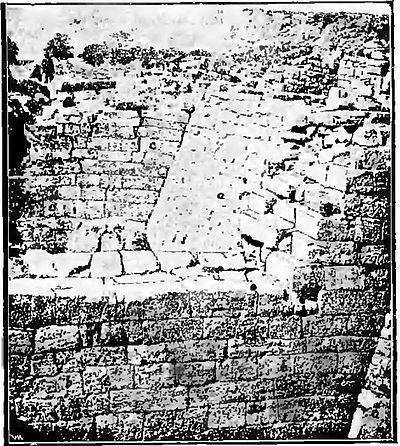

Such differences in the style of stone work are recognized in fig. 9 and fig. 10. In the former we see a projecting angle of the building VI M, and observe how well-wrought and how closely fitted are the stones at the corner, while in the lower part of the

Fig. 9.Retaining Wall of VI M

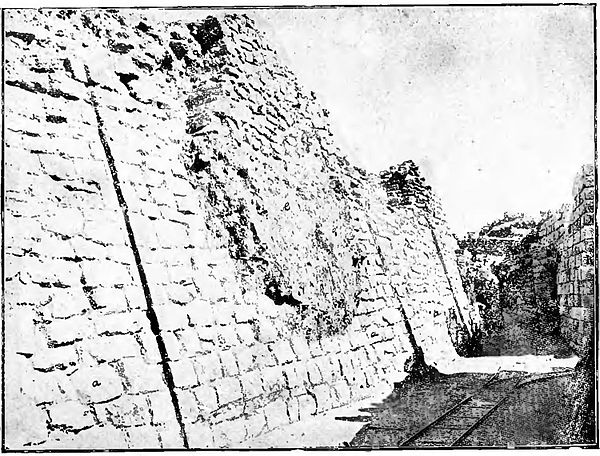

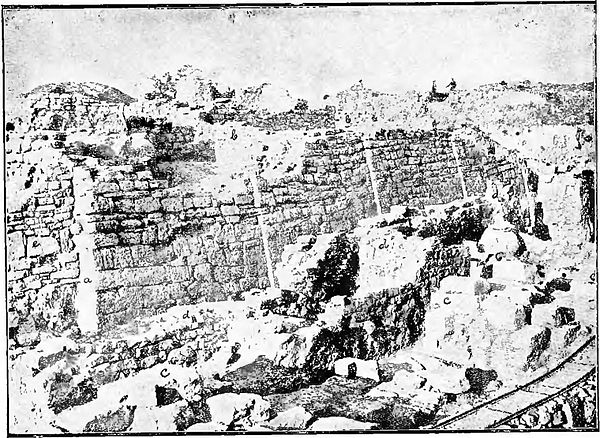

wall the blocks become more irregular and the interstices are filled with rubble. In the latter figure there is seen a portion of the Tower VI h projecting from the East Citadel Wall. It will be noted that the city wall (c) shows on its scarped surface irregular stones, in contrast to which the blocks of the tower wall appear well-wrought and with such regular interstices that they remind us of the fine Hellenic isodomous masonry.

9. Building Material.[3]Originally a brick upper wall, later replaced by stone, was built upon the solid lower wall of the stronghold. Clay was employed in the construction of the horizontal roofs of the houses. The building material for the timbers of the roof, for the platform inside the towers, for the beams in some of the walls, for the pillars and doors, was wood. The parastades, on the other hand, seem to have been built of stone, not of wood as in the case of the II

Fig. 10.North Wall of Tower VI h

Stratum. In the construction of the pavement burnt lime was used, as is seen on the steep ascent near the building VI M, leading from the South Circuit Wall to the high terrace of the inner citadel. It is likely that lime cement, like the Mycenaean pottery, was an importation, since it has not been discovered elsewhere. Although great pithoi filled with that substance were unearthed in the Tower VI h, yet Dörpfeld does not believe that lime was generally used in the VI City for building material.

The Walls of the Citadel

10. The Extent.[4]The wall on the whole east side of the hill has been uncovered to its foundation. Even on the south side and in a part of the west side, where it is not fully excavated, its course is clearly defined. On the north, however, no trace remains unless it be a small fragment near the great Northeast Tower. The entire circumvallation must have measured about 540 meters. Of this circumference, 330 meters are preserved, giving us about three-fifths of the original circuit. When the other two-fifths were destroyed, we cannot fully determine. A tradition, however, preserved in Strabo XIII, 599, declares that Archaianax (about 550 B.C.) used the stones of old Ilios to build Sigeum, while still another tradition states that Achilleum was constructed from the Trojan ruins. In the modern village of Yeni Shehr, which occupies the site of Sigeum or Achilleum, there are built into several of the houses square stones which correspond in material and workmanship to the blocks of the VI Stratum. The ancient situation of both these towns to the north of Troy favors this tradition.

11. Periods of Construction.[5]The fortress wall exhibits such different styles of masonry that it is impossible to assign its whole construction to the same period. At one time must have been built the West Wall, from its western end to the Gate VI U; at another period the entire South Wall, from VI U to the Gate VI T, together with the Towers VI h and VI g which project from the East Wall. To still another period belongs the East Wall, from the Gate VI T to the Tower VI g.

The poorest style of masonry is seen in the West Wall, which, with the exception of portions repaired at a later time, consists of small unwrought stones. In the East Wall the blocks are larger and better hewn, while the best form of masonry appears in the South Wall and in the towers, where the great stones are cut into rectangular blocks and closely fitted.

12. The Projections.[6]The wall of the citadel forms a great polygon, whose sides are of equal length and whose corners are distinguished by advancing angles. These advancing angles are a survival of the same style of masonry as is seen on a scale almost twice as large in the vast circumvallation at Gha, near Lake Copaïs—an architectural feature which shows a marked correspondence between the Mycenaean fortress of Boeotia and Mycenaean Troy. They occur also at Tiryns, in old Egyptian walls, and sometimes even in Greek walls of classical times. The projections in the walls of Troy vary in depth from 0.10 m. to 0.15 m., and in a few cases to 0.30 m.

13. West Wall.[7]Even though the West Wall shows weaker construction than the others, yet it forms a strong defense. Its perpendicular superstructure is completely destroyed, while exposure to the air has caused such injury to the outside of the lower wall that we can scarcely distinguish a ressault, or advancing angle. Its scarp is about 0.40 m. to every meter in height. We note in fig. 11 two essentially

Fig. 11.West Wall

Well-dressed blocks are shown at a, and irregular stones at b.

different portions of the West Wall. On the left (a) the stones are well-dressed and quadrangular, while on the right the masonry shows irregular blocks filled in with rubble. There can be little doubt that the ruder masonry is the older, while the more advanced style of building is a later restoration, probably contemporaneous with the building of VI A, since the repairing of the wall extends from the Gate VI U to the northwest corner of this structure.

Fig. 12.East Wall

The city wall is seen at a with a portion of the upper wall at d. In the distance is the East Gate. At h are seen foundations of the Athena Precinct of the Roman Ilion, while above the débris c is the wall g of the VIII stratum.

14. East Wall.[8]The frontispiece shows the strongly scarped substructure of the East Wall, rising 4 m. to 5 m. in height. A portion of the superstructure (e), belonging to the north side wall (b) of the Tower VI h, is seen above the city wall (a). In several places the upper citadel wall also can be distinguished by the small regular stones used in its construction. Figure 12 gives a clearer view of this East Wall, showing the style of wrought stone, the interstices, and the projecting angles. A small portion of the upper wall can be noted at d, while in the distance is seen the Gate VI S.

The lower wall is about 6 m. high and 4.60 to 5 m. thick, with a scarp of something like 0.37 m. to every meter in height. It is rendered more firm and solid by the inward slope of the layers of stone. Above this massive substructure is built the upper wall, 1.80 m. to 2 m. thick, which rises to-day, in its best-preserved portions, 2 m. high. The stones of which it is constructed are small and quadrangular. They were used in its erection sometime during the existence of the VI City, since remains of clay brick in the great Tower VI g show unmistakably that the entire superstructure originally consisted of this material. Throughout its whole extent the East Citadel Wall, which exhibits the same style of masonry from the Tower VI g to the Gate VI T, curves at no point, but forms an immense polygon. Each side is about 9 m. long, and, projecting beyond its predecessor, makes a solidly constructed advancing angle.

15. South Wall.[9]The South Wall, owing to the greater measurements of its stone, is more stately in appearance than the East Wall. Its blocks, 1.50 m. long and 0.30 m. high, are well-wrought and so closely joined that no rubble is needed to fill the interstices. The scarp is about 0.23 m. to every meter in height. A small portion of this wall is seen in the foreground of fig. 25, where we observe the well-dressed rectangular blocks of stone. It is similar in its masonry from the Gate VI T on the south to the Gate VI U on the southwest, and was provided with the same kind of advancing angles as was noted on the East Wall.

It is a puzzling question to explain the difference in masonry as seen in the wall of our fortress. Did the builders so advance in their art while erecting this circumvallation of over five hundred meters that they were able to finish in well-dressed rectangular blocks of stone the wall which they had begun in rude Cyclopean style? Dörpfeld once inclined to this view,[10] but now favors the belief that a uniform wall originally surrounded the whole hill, and during the existence of the VI City the east and south portions, which show the finest style of masonry, were entirely rebuilt.

The Gates

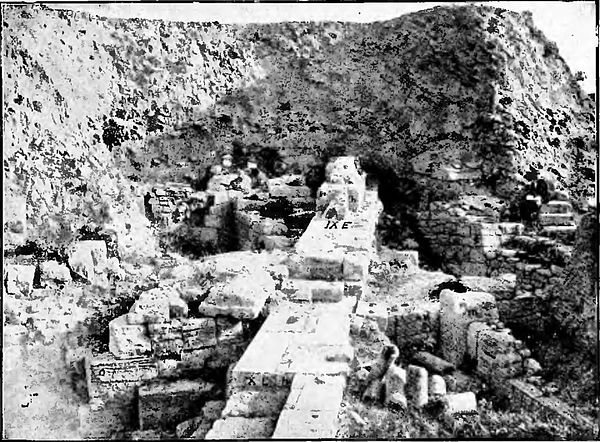

Fig. 13.East Gate

The citadel wall is marked a. Ruins of the VII Stratum are visible at f and e, while at h is seen the wall of the Athena Precinct (IX Stratum).

gate to the citadel, situated in the missing north wall.[11]

16. The East Gate.[12]This gate is well preserved, and can be seen in fig. 12 and fig. 13. The wall of the city, coming from the north and forming a bow-like projection (h g f e in fig. 14) beyond the entrance, makes a veritable cul-de-sac, where an assailant approaching from the south would be hemmed in between both walls of the fortress before he could reach the gate (a b). Such an arrangement, in a somewhat altered form, is well known to have existed at Mycenae and Tiryns.

In fig. 13 the reader will see on the left (a) the great East Wall of the city, partly covered by a fragment (f) of the gate of the VII Stratum. On the right the end of the other citadel wall incloses the gateway. The left corner is seen at b and c, but the façade is hidden by the great square wall (h) which the Romans erected as the foundation of the East Hall of the Athena Precinct.

As we enter the passageway, which is about 2 m. broad, we see on our left the wall of the city extending over 5 m. until it ends (fig. 14) at the well-preserved corner (c). The right wall is preserved to a height of only 2 m., while above it (fig. 13) lie ruins (e) belonging to the VII Stratum. Its original height was at least 4 m., since it must have had an elevation equal to that of the lower wall of the citadel. Beyond the bow-shaped gateway was the door, of which nothing remains. The opening (a b in fig. 14) is about 1.80 m. broad. The cross wall is only 1.20 m. thick, and is so loosely connected with both side walls as to form a striking contrast to the solid masonry of the fortress. A ramp ran from the gateway to the interior of the city, for at v two steps are found leading to the terrace of the buildings VI E and VI Q. At the right and left is free access to

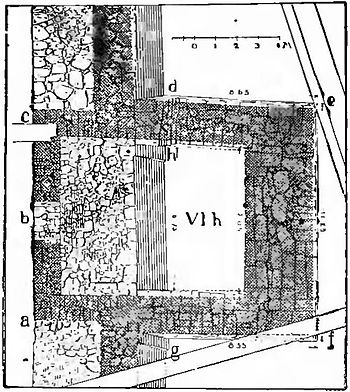

Fig. 14.Ground Plan of East Gate

the space between the circuit wall and the wall of the first terrace.

Fig. 15.South Gate and South Tower

Over the walls of the tower extend foundations (IX E) belonging to the Roman Ilion.

opened upon the great plateau of the later lower town, and consequently was especially fitted by nature as an approach to the fortress.

We can note the position of this gate in fig. 15. Its ground plan, as it remained during the existence of the VI City, without the walls of later structures, is seen in fig. 16. The gateway is 3.20 m. to 3.35 m. in breadth, and is paved with blocks of stone, beneath which is a canal 0.50 m. deep and 0.30 to 0.40 m.

Fig. 16.Ground Plan of South Gate

wide for the carrying off of rain water. Since this entrance was in use during the time of the VII and VIII settlements, there is some doubt as to whether the canal and pavement belong to the Mycenaean City. On its east side the gateway is flanked by the citadel wall (d g), 5 m. thick, while on the west there juts out beyond the citadel wall, which is here only 2.20 m. thick, a massive rectangular tower (r l o p), constructed at a later period. In earlier times only a tower-shaped projection (s p t u) extended from the fortress. Two unwrought blocks of stone, perhaps belonging to the VII Stratum and evidently intended

to guard the corners, stand at the front angles (g l)

of the gate.

18. The West Gate.[14]We can note something of the form of the West Gate VI U in fig. 17, although

Fig. 17.Ground Plan of West Gate

it has suffered great destruction and later buildings

have been erected upon it. The South Citadel Wall

(h g f) ends abruptly at e f, while the West Citadel

Wall (a b c) terminates with equal abruptness at c d.

The ends of these two walls form a gateway 4 m.

wide. No tower projecting from the wall (b c) flanks

the passage, as at the Gate VI T, although it is possible

that such once existed and was later destroyed when this entrance was walled up. The gateway bends toward the right, giving access by a gradual incline to the street between the South Wall and the building VI M, as well as to the first terrace of the citadel. A retaining wall (d k m), which borders the passageway on one side, is preserved only at its two ends. It is likely that there was a paved ramp at the corner (m). A wall serving as a doorsili and an erect stone of the door pillars (k) show where probably the door inclosure (i k) must have been. We can infer that the breadth of the opening was something like 2.50 m. A piece of a canal (s) is seen within the passage.

During the time of the VI City the gate must have been completely closed, as a wall between c d and f e indicates. This wall, on account of its masonry, is to be assigned to the period of the VI Stratum; furthermore, we know that the inhabitants of the VII Stratum used the same wall in the construction of their houses. The reason for walling up this entrance may have been that in the war which resulted in the destruction of the city it was found that the fortress could be more easily defended by reducing the number of gates.

The gateway VI U shows somewhat larger measurements than the two gates VI S and VI T; but we can hardly suppose that it formed the chief entrance, since the direction of VI T, as we have shown above, favored its being the principal gate to the citadel.

The Towers

The three towers of the fortress are very similar in their masonry, and were doubtless later additions to the citadel wall. Since the Tower VI g contains some remains of its original brick superstructure, we are led to infer that it is older than the Towers VI h and VI i, which show no trace that their upper wall was ever built of anything but stone.[15]

19. The South Tower.[16]We have seen that the great rectangular Tower VI i (fig. 16) was erected later than the bastion (s p t u), and that it projects from a part of the city wall which is only 2.20 m. thick. Within the tower has been found an inner room 5.70 m. long and, in the center, 5.30 m. broad. A door (a), which in later times was walled up, opened on the north. The purpose of the foundations (q) is not known, since they are not near enough to the center of the inner room to serve as a base for a supporting pillar. The sides of the tower are of varying thickness. The front wall is 4.40 m. broad, while the side walls are not over 2.20 m. The right wall, forming an angle at k, bulges out to a greater width, thus furnishing stronger protection for the corner (g) of the city wall on the east of the Gate VI T. The tower walls are preserved only to a height of 2 m. Consequently we can get no conception of the upper structure of either the gate or the tower. Two very remarkable stones (m n in fig. 15), the purpose of which is unknown, are situated before the front wall of the tower. There can be no doubt that they must he assigned to the VI City.

20. The East Tower.[17]The Tower VI h, erected to flank the East Citadel Wall, lies midway between the two gates VI S and VI T. It juts out 8 m. beyond the city wall and is over 11 m. in breadth. The tower forms a rectangle, of which the right half (d e f g in fig. 18) extends beyond the East Wall, while the left half (c a) rises higher, forming an upper story. Its

Fig. 18.Ground Plan of East Tower

masonry resembles that of the South Citadel Wall. The contrast between this style of building and that of the East Wall can be noted in fig. 19, where we see the scarped East Wall (a), the north (b) and the south (c) walls of the tower. It will be observed that the city wall (a) consists of smaller and more irregular stones. On the right of the picture are to be seen two pieces of the upper story of the tower, consisting of small but regular stones (d). The foundation is not so solid as that of the East Wall—a fact which has caused the rents visible in the tower walls at c. The thickness of the front wall (e f in fig. 18) is about 3 m., while that of the side walls (d e and g f) is about 2 m. The existence of numerous holes in

Fig. 19.East Tower

both side walls leads us to assume that at the top of the tower a horizontal platform was supported by wooden timbers extending lengthwise, on which were laid the strong floor beams. It is probable that upon these were placed planks and reeds, which were covered with a layer of earth. The lower inner room, which must have been about 3 m. high, extended to the outside wall of the citadel, while the upper room reached some distance beyond, until shut in by the wall (a c).

Although the walls of the upper story of the tower are only about 1.22 m. thick, yet their strength was certainly sufficient, since tower walls were not so exposed to the attacks of a besieging host as was the wall of the citadel itself. A door (b) led into the upper story, but the lower story was inaccessible except by steps from above. The advanced style of masonry of the Tower VI h, seen in fig. 19, shows that it was one of the latest additions to the city wall.

21. The Northeast Tower.[18]The great Northeast

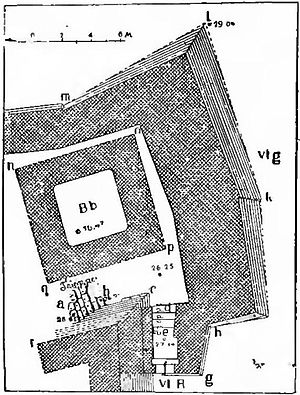

Fig. 20.Ground Plan of Northeast Tower

Tower, seen in fig. 20, is the most stately tower of the VI City. It inclosed a great rock spring (B b), 4 m. square, while near by are several steps which led to the higher ground of the citadel.

This tower (fig. 21) was situated where the East Wall of the city ended on the north, and was entered by a door (f). In order that the passage might not be diminished when the door swung back, there was a deep niche immediately behind the entrance for the reception of the door-wings. Beyond this are four steps leading to the inside of the tower, where is the gi'eat spring (B b), surrounded by a wall 2 m. thick. At the left of the passageway, in the interior of the tower, are the steps (b a), which are not so well wrought as those within the gateway. These must have furnished communication between the tower and the interior of the citadel. The inhabitants of the city could descend these steps to reach the spring, or else, turning to the right, pass outside the wall, through the gateway. The lower part of the spring is cut out of the solid rock. The upper portion is built of small stones belonging to the VII Stratum, but traces have been found of an earlier and thicker wall of large stones. The rock-hewn portion of the spring is presumably 7.50 m. deep, showing that the spring itself must have lain 10 m. below the VI City. The narrowest portion is 1.25 m. wide, while above and below this there was a slight increase in breadth. On the east and north the outside of the tower wall is in a good state of preservation. Above it, as we have observed, are remains of the earlier superstructure of unburnt brick.

This massive tower projects 8 m. beyond the citadel wall, and is 18 m. broad. Its masonry (fig. 20), so compact and so polished on the outside, makes it seem strange that such a building can be ascribed to Mycenaean times, when we consider the rude

Fig. 21.Great Northeast Tower

On the left is seen the Roman wall, and on the right the steps on the VIII Stratum.

Cyclopean walls of Tiryns and Mycenae;[19] but the same style of building in structures inside the citadel, where was found pottery characteristic of the best Mycenaean period, establishes the fact that the city was a fortress of the Mycenaean Age. The massive stones, with their close interstices and their well-wrought surface, are visible to-day in spite of exposure to the weather and in spite of the violent destruction which the town must have suffered.

The cross section of the north corner of the tower shows that the scarp in the lower portion, which is about 3 m. high, was greater than in the upper portion, which once may have had a height of 6 m. The increase in the scarp in the lower part of a fortification, such as is seen on the northeast surface of our tower, shows the technical skill of the old builder. Should we supply a slightly scarped upper structure of brick, we should get a twice-broken line whose whole shape bears a marked resemblance to the Eiffel Tower.

In time of the Mycenaean City this massive tower, 18 m. broad, with its substructure 9 m. high, on which arose a perpendicular upper wall, dominated the whole northeast part of the citadel. The dwellers in the VII Stratum repaired the upper wall with quarry stones, while the Greek settlers of the VIII Stratum built the steps beside the tower and the walls of small stones, which we can recognize on the right of fig. 20. Even at so late a date a portion of the Northeast Tower remained visible. But this last relic of the Mycenaean Citadel was finally buried under masses of débris and the mighty walls of the Athena Precinct of the Roman Ilion.

The Inner Citadel

22. VI A.[20]The first buildings excavated lay on the

Fig. 22.Ground Plan of VI A

Fig. 23.The West Wall of VI A

The west wall of the building VI A is seen at b, and the west wall of the city at a.

traces of columns or bases of columns have been found either in the hall or in the antechamber. The several stones (a b) discovered in the upper half of the hall, to judge from their form and position, cannot have served as bases for pillars. Neither can we accept the view that wooden columns existed and were afterwards destroyed, for in that case some remains of their bases would have been found. Hence we must conclude that the roof, in spite of the great breadth of the hall, could not have been supported by interior columns.

A heap of ashes, partly buried under a house wall of the VII Stratum, was found in the center of the hall, and warrants the assumption that our building was a dwelling house. The upper walls were probably erected out of fine building stone, and their complete destruction may be due to the fact that they were utilized by the inhabitants of the VII Stratum as material for their houses. No traces of clay brick are to be found in this structure. The roof was probably horizontal, and built of earth resting upon a steep incline constructed of straw or similar material. We have no information as to the lighting of the apartment. Certainly there must have been a door between the hall and antechamber, but its size and form are unknown.

23. VI B.[21]To the north of VI A was discovered the great building VI B, fronting the southwest. Three walls of an antechamber and a small portion of a side wall of the hall are preserved. Since the antechamber agrees with that of VI A, it is likely that the whole building also was similar to it. As the proportions of VI A were 11.55 × 9.10 m., we can infer that the length of the hall VI B, which had a breadth of 11.85 m., must have had a length of about 15 m. Its walls are stronger and constructed of larger blocks of stone than are the walls of VI A. The length of these blocks (f in fig. 23) is over one meter, while the thickness of the foundation wall is 2.10 m. Small stones were used for filling up the interstices. The slope of the hill necessitated a greater length for the northwest wall, in order that it might be made to conform to that of the opposite side. Consequently the antechamber exhibits the irregularity of two side walls of unequal length. This building also shows no trace of pillars, since the base of porous limestone, resembling those of Tiryns and Mycenae, which was found in this vicinity, cannot with any certainty be assigned to VI B or to VI A, or even to the VI Stratum at all.

The building VI B faces the citadel wall in such a way as to form in front of its antechamber a triangular space shut in by the citadel wall and the rear wall of VI A, thus making an open court. The whole arrangement corresponds closely to the house of Paris (Ζ, 316), which consisted of an aule (court), doma (antechamber), and thalamos (hall).

24. VI M.[22]The building VI M, which lies south of those previously mentioned, differs both in situation and ground plan from the other edifices. It is built on a terrace over 4 m. high, which was approached by a broad road leading from the city wall. It does not have a hall and antechamber, but contains a number of adjacent rooms, as seen by the ground plan in fig. 24. The destruction of the upper wall leaves no indication as to how these different apartments were connected.

The stately retaining wall (fig. 25) rises 6 m. high,

Fig. 24.Ground Plan of VI M

Fig. 25.Wall of VI M

The retaining wall with advancing angles is seen at a, the inner walls at b. The south wall of the city is visible at c. Walls of the VII stratum are seen at d and e.

off and the stones have become almost shapeless. The under portion was probably protected by the ascending roadway, which ran between the retaining wall and the city wall. This must have been built to a greater height during the existence of the two periods of the VII Stratum, and in the time of the VIII Stratum it probably concealed the whole structure. The western corner (a in fig. 24) is in a good state of preservation; but the eastern corner (f), which chanced to be unearthed by Schliemann in 1872, was later destroyed.

The several inner rooms are shut in by the great retaining wall and the side walls. The large hall (t) is over 13 m. deep, while the rooms (s and r) have a depth of only 5 m. It is not likely that the walls which surround the room (n) belong to the VI Stratum. The massive steps at the north of the building, with the two inclosing walls, ascended to the second terrace of the citadel.

The presence of a scarped surface on the south wall, near the steps, indicates that there was an open court at k. The communication between this court and the inner rooms, as well as the connection of the rooms with each other, is unknown. A canal leading through the west wall, and a great pithos, were found in the room (r). The hall (t) was cut into two sections (h and i) by a poorly built cross wall. In the former (h) were unearthed six great pithoi, and in the latter (i) a strangely formed cylindrical vessel, 0.80 m. in height and 0.40 m. in diameter, as well as numerous millstones and about fifty weaving implements. These finds would indicate that the building was a dwelling house.

The wall on the north of the steps (m l) may belong to another building designated VI N, but as to its form and position we have no indication.

Both on the west and east of VI M a ramp led to the inner part of the citadel. The buildings of the VII Stratum are built over the western ramp which is still to be recognized in the layer of small stones and earth out of which it was constructed. The east

Fig. 26.Ramp of Mycenaean Troy above the Wall of the V City

ramp was partially destroyed by the great north trench dug by Schliemann in 1872,[23] and its eastern portion alone remains. Under the later masonry of the VII and IX Strata, a little to the west of the bit of wall VI L (seen in the square 7 E in the Plan of the Citadel), is a limestone pavement. The course of this road, designated b in fig. 26, lies above the wall (a) of the V Stratum. The circular piece of wall, VI L, belongs to our city, and may mark the place where the road leading from the Gate VI T turned northward in order to reach the ramp that led toward the summit of the acropolis.

25. VI G.[24]Passing toward the east side of the citadel, we find small ruins (VI K, VI H, VI J) of the walls of buildings discovered at the east of the unexcavated portion that lies to the north of the Gate VI T. The first important structure that confronts us is VI G, which has been cut in twain by the great southeast trench dug by Schliemann in 1873.[25] On the northeast of this trench a rectangular piece of wall, with an inner wall beside it, is preserved. Of the antechamber, only the small portion remains which lies at the southwest rim of the trench. The same trench may have destroyed also the cross wall which separated the antechamber from the hall. If this be so, our building, which faced the southwest, must have consisted of an antechamber and a large hall, 11 m. long and 6 m. broad. Behind this was a small apartment that might have been used for a rear room, were it not for the fact that the northeast wall is closed, thus affording no passageway. In this room, as well as in the hall, several pithoi have been discovered. The masonry consists of small, poorly wrought stones, and resembles that of the East Wall of the city.

Southeast of VI G a portion of wall belonging to the VI Stratum has been found lying close to the citadel wall, but we have no indication of the purpose which it served.

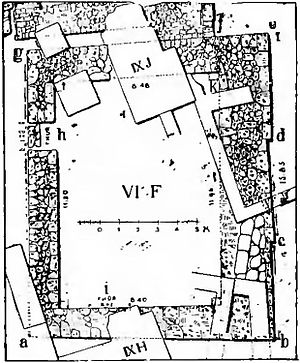

26. VI F.[26]The ground plan of the building VI F (fig. 27), which is probably a dwelling house, forms a trapezoid. Its single hall is about 8.50 m. in breadth. Its west side is 11.50 m. long, its east side 12 m. long. The walls are not of equal thickness,

Fig. 27.Ground Plan of VI F

for the east wall (b e) formed the retaining wall of the high terrace where the building stood, and consequently it is built to a thickness of 2.60 m., while the other walls measure only 1.50 m. The outside of this retaining wall shows two advancing angles, somewhat greater than those in the retaining wall of VI M and in the outer wall of the city. There are two doors—the larger (i), 2.07 m. broad in the south wall; the smaller (h), 1.40 m. broad in the west wall. The former (i) was walled up in later times. The whole structure shows a style of masonry inferior to that of the other buildings of the VI City. Its poorly wrought stones are in striking contrast to the finely polished blocks of the adjacent building, VI E. A horizontal layer of earth, which appears between the layers of stone at the outside of

Fig. 28.Ground Plan of VI E

e f, indicates that a horizontal wooden beam was once built into the masonry. A similar architectural device is seen in the court wall of the palace of Mycenae, as well as in some of the buildings of the II Stratum.

27. VI E.[27]The stately building VI E has a form (fig. 28) similar to the one which we have just discussed, and, like it, was probably a dwelling house. The large inner room is 6.40 m. broad. The length of the east wall is 9.8O m., and that of the west wall lO m. The excellent masonry (seen in fig. 29) consists of polished stones, closely joined together, forming a marked contrast to that of the Cyclopean walls of Tiryns and Mycenae, and indicating that the structure must have been erected during the later period of the Mycenaean City. There is a trace of a door (i) in the corner of the southwest wall, but it leads, not into an open space, but to the door (k) of the building VI C. Such a position makes it uncertain whether this door belonged to the VI City. Perhaps the original entrance was in the north wall; but, owing to the rained condition of this wall, it cannot be distinguished.

28. Remaining Buildings of the First Terrace.[28]To the north of VI E are the remains of two buildings, VI Q and VI P, which undoubtedly were situated on the broad road beside the city wall. Their ground plan must have been similar to VI E and VI F. The north corner and two pieces of the side wall of VI Q are preserved. The wall ran parallel to the city wall, and must have been a scarped retaining wall, thicker than the others. Its masonry shows that the building belonged to a later period of the VI City. The breadth of the inner room was about 6.50 m. and its length 15 m. A broad ramp led from the Gate VI S, between the buildings VI Q and VI E, to the center of the citadel. Close by the north corner of VI Q a single wall is found belonging to a building which is designated VI P.

All these buildings which we have described—i. e.,

Fig. 5.Walls of VI E

The retaining wall of the building VI E is seen at a and b, the rear wall at d.

VI A, B, M, G, F, E, Q, P—lay on the first terrace, which must have contained a total number of at least eighteen houses.

29. VI C.[29]The remains of the buildings which were built upon the second terrace are very scanty. The ground plan of the structure VI C alone can be determined. One of its walls was injured by the great trench which was dug in 1882. The building consists of a large hall 15.30 m. long, and, in the western portion, 8.40 m. broad. Whether it formed a trapezoid like VI E and VI F, with its greater width on the east, cannot be determined, owing to the destruction of the north wall. In front of the hall is a very small antechamber facing the west. The masonry of the foundation is of unwrought stone. The walls vary in thickness, as seen in fig. 30. The east wall, which is the strongest, has a thickness of about 1.90 m., while the thickness of the side walls is 1.40 m., and that of the west wall only 1 m. The greater strength of the east wall may be due to the fact that it served as a retaining wall of the second terrace. The roof beams must have rested on the two side walls, a fact which can account for the weakness of the west wall. Within the large hall a stone base (f) has been found in situ, which is the only sure indication of columns in all the buildings of the VI City. Its position shows that there must have been two other bases at g and h, in order to give a row of supporting columns in the middle of the building. The base, which is cylindrical, is 0.28 m. high and 0.62 m. in diameter at the bottom, and 0.57 m. at the top. It rests upon an irregular stone foundation, and must have supported a wooden column of only 0.38 m. in diameter. There is a door in the east wall, designated e d in the ground plan, but it is doubtful whether it belongs to the time of the Mycenaean City. We should expect a door in the west wall, opposite the line of columns, between the hall and the antechamber, but no trace of it is found. Such was the

Fig. 30.Ground Plan of VI C

position of the door in the temple at Neandria, which shows so many points of resemblance to our building that Dörpfeld suggested that VI C may have been a temple.

The remains of the other buildings of the VI City are so scanty that no idea can be formed of their plan or situation. It is likely that these ruins are situated on the second terrace. In the center of the citadel no part of the Mycenaean fortress remains.

30. Streets.[30]A description of the streets leading from the gates to the ascending terraces of the citadel has been given in the discussion of the various buildings. As we enter through the gates we find ourselves on the circuit road which lies between the city wall and the houses of the first terrace. Originally this wide avenue may have extended around the whole hill, but in later times it was interrupted by buildings, such as VI A, lying adjacent to the city wall. Steep ramps led to the upper terraces. The position of three of these in the Plan of our Citadel is at B 6, D 7, and J 4. Others surely existed, but are either partly destroyed or not fully excavated. Small streets, some of which ran parallel to the city wall, and others in the general direction of the ramps, separated the houses. Near the South and East Gates the pavement is constructed of stone slabs. The ascending road in the square D 7 was built of stones and lime. Two other ramps were paved with small stones and earth.

31. Springs.[31]Natural springs furnished water in the time of Mycenaean Troy. Deep wells were constructed within the citadel. Several belonging to the time of the VI City and of the later settlements have been found. The great Northeast Tower (VI g) guarded the most important of these wells (B b), which has been described in the discussion of the tower. On the broad road between the East Wall of the city and the building VI F a second well (B c) has been unearthed, which is undoubtedly of the Mycenaean period. At the top are parts of two large pithoi, placed one above the other and walled in with small stones. This portion lay above the level of the VI City. Underneath the upper structure the well was built of small stones, while below the masonry the pit was hewn deep into the rock. We can infer that this spring was used also by the inhabitants of the VII City. A third well has been found between the building VI Q and the Tower VI g. There is some doubt as to its belonging to the VI Stratum. It consists of a rectangular pit, completely walled in, about 13 m. deep, with a farther extension into the rock of 1.50 m. An underground passage about 3 m. below the level of the IX Stratum connected with the shaft, thus indicating the height at which the spring once ended. During the existence of the IX City a small round temple of marble stood over the mouth of the well. The excavations show that wooden frames were inserted in the masonry where the wall rests upon the rock, as well as higher up. This introduction of wooden beams into stone work we have noted already in the retaining wall of VI F.

32. Review of the Citadel.[32]What do we note in the Mycenaean City? We see (1) an imposing circuit wall, showing earlier and later styles of building; (2) resting on this massive substructure a perpendicular upper wall, built originally of brick and later of stone; (3) three strong and mighty towers flanking the city wall; (4) three great gates, one of which was walled up during the existence of the city, and a door affording access to the Northeast Tower; (5) individual dwellings within the citadel, separated by broad and narrow streets; (6) concentric terraces, ascending toward the center of the city; (7) a broad circuit road between the first terrace and the city wall, with ramps leading up to the summit of the acropolis; (8) several wells within the citadel.

The demolition of the upper wall of the city, the ruin of the gates, and the destruction of the walls of the inner buildings could have been wrought only by hostile hands. In several places are seen traces of an extensive conflagration. About the date of the great catastrophe we can judge only approximately. The presence of Mycenaean pottery establishes the fact that the city belonged to the period of Mycenaean culture. The damage to the walls from exposure to the weather during the existence of the VI City and the gradual increase in the elevation of the ground between several buildings show a period of long duration. We can conjecture that the city flourished between 1500 and 1000 B.C., a date which corresponds to that given by tradition for the fall of Homer's Troy.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 107–108, 1903. Cf. Dörpfeld, Mitth. Ath., pp. 380–394, 1894; Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893; Schliemann, Bericht über die Ansgrabungen in Troja im Jahre 1890; Schuchhardt-Sellers, Schliemann's Excavations, Appendix I, 1891.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 109–111. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 30–36; Heinrich, Troja bei Homer und in der Wirklichkeit, p. 35; Tsountas and Manatt, The Mycenaean Age, Appendix A, p. 371, 1897.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und llion, p. 111.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 112–113. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 38–46; Dörpfeld, Mitth. Ath., 1894, 382 ff; Heinrich, op. cit. pp. 38–39; Tsountas and Manatt, op. cit. pp. 309–370.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, p. 113. Cf. Dörpfeld, Mitth. Ath., 1894, p. 385; Heinrich, op. cit. p. 35; Tsountas and Manatt, op. cit. p. 370.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja uiid Ilion, pp. 119–120. Cf. Dörpfeld, Mitth. Ath., 1894; Heinrich, op. cit. p. 35; Tsountas and Manatt, op. cit. pp. 370, 376; Noack, Mitth. Ath., 1894, pp. 435 ff.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja uud Ilion, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 116–119.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 121–123.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Mitth. Ath., 1894, p. 385.

- ↑ Dörpteld, Troja und Ilion, p. 126. Cf. Dörpfeld, Mitth. Ath., 1894; Heinrich, op. cit. p. 35; Tsountas and Manatt, op. cit. pp. 370–371.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 126–131.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 131–133.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 135–139.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und llion, p. 139. Cf. Dörpfeld, Mitth. Ath., 1894; Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 46–56; Heinrich, op. cit. 35; Tsountas and Manatt, op. cit. p. 371.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und llion, pp. 133–135.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 139–144.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 144–151. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 43, 46–50.

- ↑ Cf. Dörpfeld, Introduction to Tsountas and Manatt's The Mycenaean Age, p. xxx.

- ↑ Dörpteld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 151–153. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 15–20; Schliemann's Bericht über die Ausgrabungen in Troja im Jahre 1890.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und llion, pp. 153–155. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 20–23.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 155–161.

- ↑ Cf. Schliemann, Ilios, p. 24.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 161–162. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, p. 29.

- ↑ Cf. Schliemann, Ilios, p. 34.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 162–163. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 164–169. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, p. 169.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 170–175. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 22–25; Koldewey, Neandria, 51. Programm zum Winkelmannsfest, 1891.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, p. 175.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 175–181.

- ↑ Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 182–183. Cf. Dörpfeld, Troja, 1893, pp. 9–13; Dörpfeld, Mitth. Ath., 1804, pp. 380 ff.; "Trojanische Frage durch die Ausgrabungen gelöst." Dörpfeld, Lecture before Harvard University, October 13, 1896.