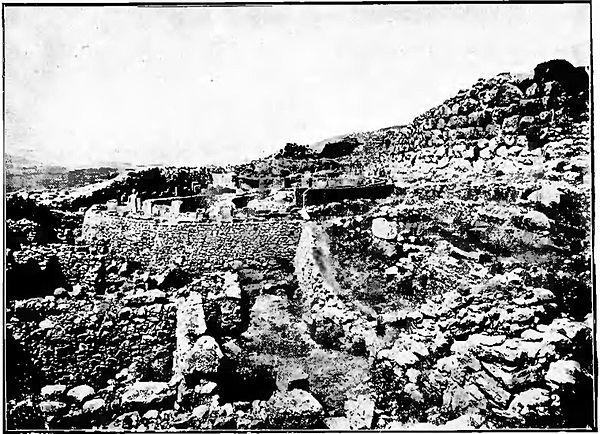

Fig. 31.Circle of Shaft-Graves at Mycenae.

THE MYCENAEAN CIVILIZATION

33. Extent.What do we mean by "Mycenaean pottery," "Mycenaean Troy?" The term "Mycenaean" is roughly applied to those palaces, dwelling houses, tombs, pottery, weapons, gems, and ornaments which exhibit a similarity, more or less striking, to those found on the citadel of Mycenae—monuments which evidently are the work of one and the same race. Recent excavations have shown the extent of Mycenaean influence to be broader than scholars of a few years ago even dreamed of believing. We venture to burden the reader with a list of some forty localities which unmistakably had come in touch with this civilization. It is noteworthy how many districts mentioned in the Homeric poems are here included. In addition to the monuments at Mycenae, Tiryns, and Hissarlik,[1] Mycenaean remains have been found at the Argive Heraeum,[2] Nauplia,[3] Midea[4] (near Nauplia), Asine[5] (in Argolis), Kampos[6] (near ancient Gerenia), Arkina[7] (six hours from Sparta), Vaphio[8] (the ancient Pharis; cups of exquisite workmanship found), Pylus[9] (Nestor's home), Phigalia,[10] Masarakata[11] (in Cephallenia), Megara,[12] Menidi[13] (seven miles from Athens), Spata[14] (nine miles from Athens), Thoricus[15] (in Attica), Acropolis of Athens[16] (prehistoric palace), Halike[17] (ancient Halae Aixonides, southeast of Athens), Kapandriti[18] (ancient Aphidna), Eleusis,[19] Salamis,[20] Aegina,[21] Calauria,[22] Gha[23] (near Lake Copaïs, identified by some with the Homeric Arne; extensive remains of prehistoric palace found), Orchomenos[24] ("Treasury of Minyas"), Thebes,[25] Tanagra,[26] Lebadea,[27] Delphi,[28] Daulis,[29] Goura (Phthiotis), Dimini[30] (three miles to the west of Volo, the ancient Iolcus), Melos[31] (four superimposed settlements, the last of which is Mycenaean), Ialysus[32] (in Rhodes), Thera,[33] Crete[34] (prehistoric palace at

Fig. 32.False-Necked Amphora from Crete

Cnosus, and extensive Mycenaean remains at Goulas, Gortyna, Courtes, Kavousi, Marathokephala, Anavlochus, Erganos), Cyprus,[35] Egypt,[36] Sicily,[37] Italy.[38]

34. Pottery.Of Mycenaean pottery we distinguish two main types: the older dull type, ornamented with linear decorations—e. g., spirals, parallels, circles, curved and straight lines—painted in dark red, violet, brown, but sometimes white; the later lustrous type, adorned with geometric patterns, bands, spirals, but more generally with scenes from marine life—e. g., the starfish, the cuttlefish, seaweed, etc.—sometimes with birds, and later with animals and men, brilliantly glazed in red, brown, and less frequently in white.

35. Date.The discoveries now being made in Crete seem to point to that island as the home of the Mycenaean cultus. The prestige of Mycenae may have followed the decline of Cretan supremacy. At any rate, 2000 B.C. is not too early a date at which to place the most flourishing period of this civilization in Crete, for Mycenaean remains have been found in Thera buried under volcanic débris of an eruption of about 1800 B.C.[39] Legends of a vast Cretan empire are probably reminiscences of that mighty maritime nation, once supreme on Mediterranean waters.

- ↑ Schliemann, Mycenae and Tiryns; Schuchhardt-Sellers, Schliemann's Excavations; Tsountas and Manatt, The Mycenaean Age; Frazer, Pausanias, III, 97–230; Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion.

- ↑ Report of American School at Athens; American Journal of Archaeology.

- ↑ Frazer, Pansanias, III, 141; Πρακτικὰ τῆς Ἀρχαιολ. Ὲταιρίας, 1892, 52.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., III, 231; Mitth. Ath., 17, 95.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., V, 601.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., III, 136; Τσοῦντας, Πρακτικὰ τῆς Ἀρχαιολ. Ὲταιρίας, 1891, 23.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., III, 136; Ἐφημερὶς ἀρχαιολογική, 1889, 132.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., III, 134; Gardner, New Chapters in Greek History, 70; Brunn, Griechische Kunstgeschichte, I, 46.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., V, 608; Bulletin de Corresp. Hellénique, 20, 388.

- ↑ Milchöfer, Anfänge der Kunst in Griechenland, 54.

- ↑ Wolters, Mitth. Ath., 19, 488.

- ↑ Furtwängler und Löschcke, Mykenische Vasen, 53.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., III, 137; Lolling, Mitth. Ath., 12, 139.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., III, 143; Mitth. Ath., 2, 82.

- ↑ Fraser, op. cit., III, 138, Δελτίον ἀρχαιολογικόν, 1890, 159.

- ↑ Tsountas and Manatt, op. cit., p. 8.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 9.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., III, 144.

- ↑ Furtwängler und Löschcke, op. cit., 40; Gazette archéologique, 8, 248.

- ↑ Tsountas and Manatt, op. cit., 387.

- ↑ Ibid., 388–394; Evans, Journal of Hellenic Studies, XIII, 195.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., V, 596; Mitth. Ath., 20, 267.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., V, 121; Tsountas and Manatt, op. cit., 374.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., V, 188.

- ↑ Furtwängler und Loschcke, op. cit., 43.

- ↑ Furtwängler und Löschcke, op. cit., 43.

- ↑ Ibid., 42.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit. V, 398; Bulletin de Corresp. Hellénique, 18, 195.

- ↑ Furtwängler und Löschcke, op. cit., 43.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., III, 140; Mitth. Ath., 9, 99.

- ↑ Annual Report of British School, 3, 1.

- ↑ Frazer, op. cit., III, 147; Furtwängler und Löschcke, op. cit., 1.

- ↑ Fouqué, Santorin et ses Éruptions.

- ↑ A. J. Evans, Journal of Hellenic Studies; Halbherr, American Journal of Archaeology; Boyd, American Journal of Archaeology.

- ↑ Murray, Smith, and Walters, Excavations in Cyprus.

- ↑ Flinders Petrie, Journal of Hellenic Studies, 11, 271.

- ↑ Furtwängler nnd Löschcke, op. cit., 47.

- ↑ Ibid., op cit., 48.

- ↑ Fouqué, Santorin et ses Éruptions, argues for 2000 B.C.